An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Sleeping hours: what is the ideal number and how does age impact this?

Affiliations.

- 1 Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada, [email protected].

- 2 Department of Pediatrics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, [email protected].

- 3 School of Human Kinetics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, [email protected].

- 4 School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, [email protected].

- PMID: 30568521

- PMCID: PMC6267703

- DOI: 10.2147/NSS.S163071

The objective of this narrative review paper is to discuss about sleep duration needed across the lifespan. Sleep duration varies widely across the lifespan and shows an inverse relationship with age. Sleep duration recommendations issued by public health authorities are important for surveillance and help to inform the population of interventions, policies, and healthy sleep behaviors. However, the ideal amount of sleep required each night can vary between different individuals due to genetic factors and other reasons, and it is important to adapt our recommendations on a case-by-case basis. Sleep duration recommendations (public health approach) are well suited to provide guidance at the population-level standpoint, while advice at the individual level (eg, in clinic) should be individualized to the reality of each person. A generally valid assumption is that individuals obtain the right amount of sleep if they wake up feeling well rested and perform well during the day. Beyond sleep quantity, other important sleep characteristics should be considered such as sleep quality and sleep timing (bedtime and wake-up time). In conclusion, the important inter-individual variability in sleep needs across the life cycle implies that there is no "magic number" for the ideal duration of sleep. However, it is important to continue to promote sleep health for all. Sleep is not a waste of time and should receive the same level of attention as nutrition and exercise in the package for good health.

Keywords: guidelines; life cycle; population heath; public health; recommendations; sleep.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Disclosure The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Normal self-reported sleep durations in…

Normal self-reported sleep durations in children aged 0–12 years. Note: The mean reference…

Normal actigraphy-determined sleep duration values…

Normal actigraphy-determined sleep duration values in children aged 3–18 years. Note: The mean…

Sleep duration estimates of Canadians…

Sleep duration estimates of Canadians (dashed line) compared with the sleep duration recommendation…

Similar articles

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, Moraleda C, Rogers L, Daniels K, Green P. Crider K, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1;2(2022):CD014217. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014217. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022. PMID: 36321557 Free PMC article.

- Lack of sleep as a contributor to obesity in adolescents: impacts on eating and activity behaviors. Chaput JP, Dutil C. Chaput JP, et al. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016 Sep 26;13(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0428-0. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016. PMID: 27669980 Free PMC article.

- Implementing the 2009 Institute of Medicine recommendations on resident physician work hours, supervision, and safety. Blum AB, Shea S, Czeisler CA, Landrigan CP, Leape L. Blum AB, et al. Nat Sci Sleep. 2011 Jun 24;3:47-85. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S19649. Print 2011. Nat Sci Sleep. 2011. PMID: 23616719 Free PMC article.

- [Sleepiness among adolescents: etiology and multiple consequences]. Davidson-Urbain W, Servot S, Godbout R, Montplaisir JY, Touchette E. Davidson-Urbain W, et al. Encephale. 2023 Feb;49(1):87-93. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2022.05.004. Epub 2022 Aug 12. Encephale. 2023. PMID: 35970642 Review. French.

- Consensus recommendations on sleeping problems in Phelan-McDermid syndrome. San José Cáceres A, Landlust AM, Carbin JM; European Phelan-McDermid Syndrome consortium; Loth E. San José Cáceres A, et al. Eur J Med Genet. 2023 Jun;66(6):104750. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2023.104750. Epub 2023 Mar 23. Eur J Med Genet. 2023. PMID: 36963463 Review.

- Assessing the influence of sleep and sampling time on metabolites in oral fluid: implications for metabolomics studies. Scholz M, Steuer AE, Dobay A, Landolt HP, Kraemer T. Scholz M, et al. Metabolomics. 2024 Aug 7;20(5):97. doi: 10.1007/s11306-024-02158-3. Metabolomics. 2024. PMID: 39112673 Free PMC article.

- The Effect of a Cognitive Dual Task on Gait Parameters among Healthy Young Adults with Good and Poor Sleep Quality: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Dalbah J, Zadeh SAM, Kim M. Dalbah J, et al. J Clin Med. 2024 Apr 27;13(9):2566. doi: 10.3390/jcm13092566. J Clin Med. 2024. PMID: 38731095 Free PMC article.

- Trends and regional distribution in health-related quality of life across sex and employment status: a repeated population-based cross-sectional study. Ahn SK, Seo HJ, Choi MJ. Ahn SK, et al. J Occup Health. 2024 Jan 4;66(1):uiae017. doi: 10.1093/joccuh/uiae017. J Occup Health. 2024. PMID: 38604179 Free PMC article.

- Sleep behavioral outcomes of school-based interventions for promoting sleep health in children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 years: a systematic review. Gaskin CJ, Venegas Hargous C, Stephens LD, Nyam G, Brown V, Lander N, Yoong S, Morrissey B, Allender S, Strugnell C. Gaskin CJ, et al. Sleep Adv. 2024 Mar 29;5(1):zpae019. doi: 10.1093/sleepadvances/zpae019. eCollection 2024. Sleep Adv. 2024. PMID: 38584765 Free PMC article. Review.

- Associations Among Sleep, Emotional Eating, and Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescents. White ML, Triplett OM, Morales N, Van Dyk TR. White ML, et al. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2024 Apr 5. doi: 10.1007/s10578-024-01692-4. Online ahead of print. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2024. PMID: 38578582

- Chaput JP, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6 Suppl 3):S266–S282. - PubMed

- Chaput JP, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years) BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):855. - PMC - PubMed

- St-Onge MP, Grandner MA, Brown D, et al. Sleep duration and quality: impact on lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(18):e367–386. - PMC - PubMed

- Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014;37(1):9–17. - PMC - PubMed

- Gruber R, Carrey N, Weiss SK, et al. Position statement on pediatric sleep for psychiatrists. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(3):174–195. - PMC - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Dove Medical Press

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Products or services may be offered by an affiliated entity. Learn more.

How Much Sleep Do You Need?

Staff Writer

Eric Suni has over a decade of experience as a science writer and was previously an information specialist for the National Cancer Institute.

Want to read more about all our experts in the field?

Dr. Abhinav Singh

Sleep Medicine Physician

Dr. Singh is the Medical Director of the Indiana Sleep Center. His research and clinical practice focuses on the entire myriad of sleep disorders.

Sleep Foundation

Fact-Checking: Our Process

The Sleep Foundation editorial team is dedicated to providing content that meets the highest standards for accuracy and objectivity. Our editors and medical experts rigorously evaluate every article and guide to ensure the information is factual, up-to-date, and free of bias.

The Sleep Foundation fact-checking guidelines are as follows:

- We only cite reputable sources when researching our guides and articles. These include peer-reviewed journals, government reports, academic and medical associations, and interviews with credentialed medical experts and practitioners.

- All scientific data and information must be backed up by at least one reputable source. Each guide and article includes a comprehensive bibliography with full citations and links to the original sources.

- Some guides and articles feature links to other relevant Sleep Foundation pages. These internal links are intended to improve ease of navigation across the site, and are never used as original sources for scientific data or information.

- A member of our medical expert team provides a final review of the content and sources cited for every guide, article, and product review concerning medical- and health-related topics. Inaccurate or unverifiable information will be removed prior to publication.

- Plagiarism is never tolerated. Writers and editors caught stealing content or improperly citing sources are immediately terminated, and we will work to rectify the situation with the original publisher(s)

- Although Sleep Foundation maintains affiliate partnerships with brands and e-commerce portals, these relationships never have any bearing on our product reviews or recommendations. Read our full Advertising Disclosure for more information.

Table of Contents

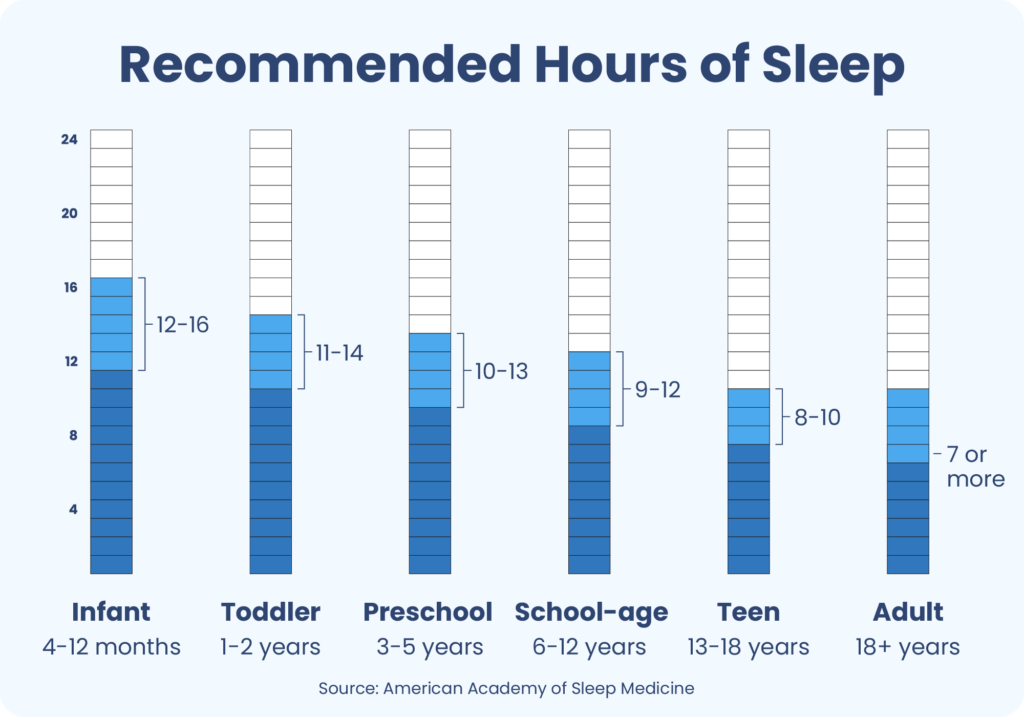

Recommended Sleep Times By Age Group

How much sleep is really necessary, how were the recommendations created, make sleep a priority.

- Most healthy adults need at least seven hours of sleep each night.

- Infants, young children, and teenagers should get more sleep to support growth and development.

- Prioritize getting enough sleep each night to stay happy, healthy, and sharp.

Healthy adults need at least seven hours of sleep per night. Babies, young children, and teens need even more sleep to enable their growth and development.

Knowing the general recommendations for how much sleep you need is a first step. Next, it is important to reflect on your individual needs based on factors like your activity level and overall health. And finally, of course, it is necessary to apply healthy sleep tips so that you can actually get the full night’s sleep that is recommended.

Essential Products for Better Sleep

Best Sleep Mask

Manta Pro Sleep Mask

Best Earplugs for Sleep

Loop Quiet Earplugs

Best Melatonin Supplements

Sleep Is the Foundation Sleep Support Melatonin Capsules

Best Sleep Coaching Program

Sleep Doctor Adult Sleep Coaching

| Age group | Age range | |

|---|---|---|

| Infant | 4-12 months | 12-16 hours (including naps) |

| Toddler | 1-2 years | 11-14 hours (including naps) |

| Preschool | 3-5 years | 10-13 hours (including naps) |

| School-age | 6-12 years | 9-12 hours |

| Teen | 13-18 years | 8-10 hours |

| Adult | 18 years and older | 7 hours or more |

Different age groups need different amounts of sleep. In each group, the guidelines present a recommended range Trusted Source National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health by providing access to biomedical and genomic information. View Source of nightly sleep duration for healthy individuals. In some cases, sleeping an hour more or less than the general range may be acceptable based on a person’s circumstances.

Sleep recommendations for newborns are not available because sleep needs in this age group vary widely Trusted Source UpToDate More than 2 million healthcare providers around the world choose UpToDate to help make appropriate care decisions and drive better health outcomes. UpToDate delivers evidence-based clinical decision support that is clear, actionable, and rich with real-world insights. View Source and can range from as few as 11 hours to as many as 19 hours per 24-hour period.

These guidelines serve as a rule-of-thumb for how much sleep babies , children, and adults need Trusted Source National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health by providing access to biomedical and genomic information. View Source while acknowledging that the ideal amount of sleep can vary from person to person. Some people need more or less sleep each night than those reflected in the ranges.

Deciding how much sleep you need means considering your overall health, daily activities, and typical sleep patterns. Some questions that you help assess your individual sleep needs include:

- Are you productive, healthy, and happy on seven hours of sleep? Or have you noticed that you require more hours of sleep to get into high gear?

- Do you have coexisting health issues that might require more rest?

- Do you have a high level of daily energy expenditure? Do you frequently play sports or work in a labor-intensive job?

- Do your daily activities require alertness to do them safely? Do you drive every day and/or operate heavy machinery? Do you ever feel sleepy when doing these activities?

- Are you experiencing or do you have a history of a sleep disorder ?

- Do you depend on caffeine to get you through the day?

- When you have an open schedule, do you tend to sleep in more?

You can use your answers to these questions to hone in on your optimal amount of sleep.

Sleep Better One Night at a Time

Sleep Doctor 28-Day Sleep Wellness Program

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine organized a panel of sleep experts to create these recommendations. The panel members reviewed hundreds of high-quality research studies about sleep duration and key health outcomes like cardiovascular disease, depression, pain, and diabetes.

After studying the evidence, the panel used several rounds of voting and discussion to narrow down the ranges for the amount of sleep needed at different ages. The final recommendations have been endorsed by other medical organizations, such as the Sleep Research Society, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and more.

Once you have a nightly sleep goal based on the hours of sleep that you need, it is time to start planning for how to make that a reality.

Start by making sleep a priority in your schedule. This means budgeting for the hours you need so that work or social activities do not trade off with sleep. While cutting sleep short may be tempting in the moment, it does not pay off in the long run because sleep is essential for you to perform at your best, both mentally and physically.

Getting more sleep is a key part of the equation, but remember that it is not just about sleep quantity. Quality sleep matters too, and it is possible to get the hours that you need but not feel refreshed because your sleep is fragmented or non-restorative. Fortunately, improving your bedroom setting and sleep-related habits, is an established way to get better rest. Examples of improvements include:

- Improving your sleep hygiene , which includes sticking to the same sleep schedule every day, even on weekends

- Practicing a relaxing bedtime routine to make it easier to fall asleep quickly

- Choosing the best mattress that is supportive and comfortable, and outfitting it with the best pillows and bedding .

- Minimizing potential disruptions from light and sound while optimizing your bedroom temperature

- Disconnecting from electronic devices like mobile phones and laptops for a half-hour or more before bed

- Carefully monitoring your intake of caffeine and alcohol and avoiding consumption in the hours before bed

If you are a parent or caregiver, many of the same tips apply to help children and teens get the recommended amount of sleep. Teens in particular face a number of unique sleep challenges to getting the sleep they need .

If you or a family member are experiencing symptoms such as significant sleepiness during the day, insomnia , leg cramps , snoring , or another symptom that is preventing you from sleeping well, you should consult your primary care doctor or find a sleep professional to determine the underlying cause.

You can try using our sleep diary to track your sleep habits. This can provide insight about your sleep patterns and needs. It can also be helpful to bring with you to the doctor if you have ongoing sleep problems.

- New Research Evaluates Accuracy of Sleep Trackers

- Listening to Calming Words While Asleep Boosts Deep Sleep

- Distinct Sleep Patterns Linked to Health Outcomes

- Association Between Sleep Duration and Disturbance with Age Acceleration

About Our Editorial Team

Eric Suni, Staff Writer

Medically Reviewed by

Dr. Abhinav Singh, Sleep Medicine Physician MD

References 3 sources.

Paruthi, S., Brooks, L. J., D’Ambrosio, C., Hall, W. A., Kotagal, S., Lloyd, R. M., Malow, B. A., Maski, K., Nichols, C., Quan, S. F., Rosen, C. L., Troester, M. M., & Wise, M. S. (2016). Consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine on the recommended amount of sleep for healthy children: Methodology and discussion. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12(11), 1549–1561.

Kirsch, D. (2022, September 12). Stages and architecture of normal sleep. In S. M. Harding (Ed.). UpToDate., Retrieved March 1, 2023, from

Consensus Conference Panel, Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D. F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M. A., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R. K., Martin, J. L., Patel, S. R., Quan, S. F., Tasali, E., Non-Participating Observers, Twery, M., Croft, J. B., Maher, E., … Heald, J. L. (2015). Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(6), 591–592.

Learn More About How Sleep Works

Can You Learn a Language While Sleeping?

How to Become a Morning Person

How Memory and Sleep Are Connected

What Causes Excessive Sleepiness?

What Causes Restless Sleep?

Biphasic Sleep: What It Is And How It Works

Polyphasic Sleep: Benefits and Risks

Sleep Inertia: How to Combat Morning Grogginess

REM Rebound: Causes and Effects

Do Moon Phases Affect Your Sleep?

Why Do We Need Sleep?

Alpha Waves and Sleep

How Age Affects Your Circadian Rhythm

How Is Sleep Different For Men and Women?

Circadian Rhythm

Chronotypes: Definition, Types, & Effect on Sleep

Sleep Drive and Your Body Clock

8 Health Benefits of Sleep

Daylight Saving Time: Everything You Need to Know

How To Get a Good Night’s Sleep in a Hotel

Does Napping Impact Your Sleep at Night?

Does Daytime Tiredness Mean You Need More Sleep?

Why Do I Wake Up at 3 am?

Sleep Debt: The Hidden Cost of Insufficient Rest

Sleep Satisfaction and Energy Levels

How Sleep Works: Understanding the Science of Sleep

What Makes a Good Night's Sleep

What Happens When You Sleep?

Sleep and Social Media

Adenosine and Sleep: Understanding Your Sleep Drive

Oversleeping

Hypnagogic Hallucinations

Hypnopompic Hallucinations

What All-Nighters Do To Your Cognition

Long Sleepers

How to Wake Up Easier

Sleep Spindles

Does Your Oxygen Level Drop When You Sleep?

100+ Sleep Statistics

Short Sleepers

How Electronics Affect Sleep

Myths and Facts About Sleep

What’s the Connection Between Race and Sleep Disorders?

Sleep Latency

Microsleep: What Is It, What Causes It, and Is It Safe?

Light Sleeper: What It Means and What To Do About It

Other articles of interest, best mattresses, sleep testing and solutions, bedroom environment, sleep hygiene.

- Best Cooling Mattresses

- Best Hybrid Mattresses

- Best Mattresses for Back Pain

- Best Mattresses for Heavy People

- Best Mattresses for Side Sleepers

- Best Mattresses for Stomach Sleeping

- Best Mattress in a Box

- Best Mattresses on a Budget

- Best Memory Foam Mattresses

- Best Online Mattresses

- Best Sofa Beds and Sofa Sleepers

- Best Lumbar Pillows for Sleep

- Best Pillows for Back Sleeping

- Best Pillows for Neck Pain

- Best Pillows for Side Sleepers

- Best Pregnancy Pillows

- Best CBD Oils for Sleep and Insomnia

- Best CBD Oils for Pets

- Best Essential Oils for Sleep

- Best Silk Pillowcases for Your Hair & Skin

- Best Sleep Gadgets to Help You Sleep

- Best Weighted Blankets

- Best Weighted Blankets for Kids

- Best and Worst Cities for Sleep

- Depression and Sleep Statistics

- Fascinating Animal Sleep Facts

Sleep Statistics: Understanding Sleep and Sleep Disorders

Ryan Fiorenzi, BS, Certified Sleep Science Coach - Updated on July 12th, 2023

Over the past ten years, sleep research has accelerated at a pace never seen before. Organizations like the Sleep Research Society , the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , the Mayo Clinic and the National Institutes of Health have shed more light on the importance of sleep. It is now known as the " third pillar " of good health.

To keep track of key findings, we track updates from trusted sources as they are published. Our goal is to simplify the key facts that come out of that research into our resources throughout the site and the statistics below. If you feel we have missed something that you think should be included, please let us know.

General Sleep Statistics

Average sleep times.

- Americans sleep 6.8 hours per day on average, which hasn't changed much from Gallup polls in the 1990s and 2000s, but is down more than an hour from 1942. 1

- 59% of Americans get 7 or more hours of sleep at night. In 1942, 84% met the standard of getting 7-9 hours per night of sleep. 1

- The older the age group, the more they report sleeping. Americans aged 65 and over report getting the most sleep, while 18-29-year-old report the least.

| Group | Sleep 6 hours or less | Sleep 7 hours or more |

|---|---|---|

| 18-29 year olds | ||

| 30-49 year olds | ||

| 50-64 year olds | ||

| 65+ year olds | ||

| Men | ||

| Women | ||

| Employed | ||

| Not employed | ||

| Less than $30,000 annual household income | ||

| Between $30,000 to $75,000 annual household income | ||

| $75,000 or more annual household income | ||

| Have children under 18 | ||

| Don't have children under 18 |

Source: Gallup, Dec. 5-8, 2013

Sleep Needs Statistics

Sleep needs by age as defined by the June 13, 2016, American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommendations that the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has endorsed. 2

| Age | Recommended Amount of Sleep |

|---|---|

| Infants aged 4-12 months | 12-16 hours a day (including naps) |

| Children aged 1-2 years | 11-14 hours a day (including naps) |

| Children aged 3-5 years | 10-13 hours a day (including naps) |

| Children aged 6-12 years | 9-12 hours a day |

| Teens aged 13-18 years | 8-10 hours a day |

| Adults aged 18 years or older | 7–8 hours a day |

- Women on average sleep five to 28 minutes longer than men. 3 The NIH found a variety of factors tied to this including differences in average lifestyle and employment.

- On average, women need 20 minutes more sleep per night. 4

Sleep Deprivation Statistics

- Adults need 7 hours or more of sleep per night for optimal health. 5 The statistics below define short sleep as less than 24 hours of sleep in 24 hours.

Prevalence of Short Sleep Duration (<7 hours) for Adults Aged ≥18 Years, by County, United States, 2014

- About one in four people aged 18 to 24 say that they don't sleep well because of technology. 5

- Sleep deprivation increases the expectation of gains and decreases the estimation of possible losses when gambling. 6

- Decision making in "high-stakes, real-world situations" is impaired when someone is experiencing sleep loss. 7

- Shift Work Sleep Disorder is a recognized medical condition for 20% of U.S. shift workers. 8

- 45% of Americans claim that poor sleep has made an impact on their daily life at least once in the last 7 days. 33

- More than 50% of Americans have taken a nap in the last 7 days. 23% took a nap 1-2 days, 13% took a nap 3-4 days, 17% took a nap at least 5 days. This may suggest that many Americans undersleep, though many countries take afternoon "siestas," and some sleep researchers theorize that humans may be wired to sleep in 2 sessions per day (in 2 sleep phases).

Sleep Disorders Statistics

Sleep disorders are very common. The NIH compiled the data below to support clinical practice guidelines for sleep disorders. 9

| Disorder | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Insomnia | 10-15% |

| Hypersomnia | Not Known |

| Obstructive sleep apnea* | 14% |

| Restless legs syndrome* | 2% |

| Delayed sleep-wake phase disorder | 10% |

| Advanced sleep-wake phase disorder | 1% |

| Shift worker disorder | 2% |

Insomnia is a sleep disorder that leads to habitual sleeplessness or an inability to sleep.

- The yearly workplace cost in the US due to insomnia is an estimated $63.2 billion. 10

- One in four women suffers from insomnia. 11 This makes them twice as likely as men to have insomnia. 12

- Approximately 6% of adults suffer from insomnia. 13

Hypersomnia

Hypersomnia is a sleep disorder that leads to excessive daytime sleepiness or time spent sleeping.

- 4% to 6% of the general population has hypersomnia. 14

- Sleep apnea syndrome leads to hypersomnia, and there is a higher prevalence of this disorder in men. 15

- Narcolepsy only affects 0.026% of the general population. It is caused by the inability to regulate sleep-wake cycles normally. 16

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is a potentially serious sleeping disorder that causes people to repeatedly stop and start breathing during sleep.

- 5% to 20% of the adult population is affected by OSAS when assessed with sleep tests. 17

- It is seen in 1% to 3% of children of preschool age. 18

- OSAS prevalence is as high as 10% to 20% in children who habitually snore. 19

Restless Legs Syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a disorder characterized by overwhelming urges to move the legs to relieve unpleasant twitching or tickling sensations.

- 11% to 29% of pregnant women are affected by RLS.

- 25% to 50% of patients with end-stage renal disease have Restless Legs Syndrome

- Limb twitching during sleep occurs in 80% of patients with RLS. 20

Delayed Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder

Delayed sleep-wake phase disorder (DSWPD) is characterized by a delayed day and night cycle, often causing someone to fall asleep and wake later in the day.

Note that statistics vary widely on this condition as the consistency around definitions and diagnostic criteria tend to vary widely.

- 51% of patients with DSWPD have had a lifetime history of depression .

- 59% of adolescents with this disorder demonstrated poor academic performance, and 45% had behavioral problems. 21

- A prevalence of up to 8 percent has been reported in American teenagers. 22

Advanced Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder

Advanced Sleep Phase Disorder (ASPD), otherwise known as Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome (ASPS), is a sleep disorder characterized by a shift in the circadian rhythm. This shift typically causes someone to go to bed earlier and wake up earlier. This is characterized by the correct quantity of sleep at undesired times of the day. Approximate averages are 8-9 pm bedtimes and 4-5 am awakenings. This disorder is not yet commonly understood.

- There is a 50% chance of passing ASPD on to children. 23

Shift Worker Disorder

Shift work sleep disorder (SWSD) is a sleep disorder characterized by excessive sleepiness and insomnia in people whose work schedules overlap with normal sleep times.

- 20% of the working population in Europe and North America is engaged in shiftwork 24

- The sleep-wake disturbance is severe enough to warrant diagnosis as SWSD in about 5 to 10 percent of night-shift workers.

- 37.5% of post-night-shift drives have been considered unsafe during testing. 25

Obesity and Sleep Statistics

Being overweight can affect sleep, and poor sleep can make it more likely to put on weight. Researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine studied 77 overweight volunteers with either prediabetes or type 2 diabetes. Many had issues getting high-quality sleep. Half of the group went on a weight-loss diet and exercise program, and the other half just followed the diet. After 6 months, both groups lost an average of 15 pounds and reduced their belly fat by 15%. The researchers concluded that a reduction in belly fat is a good way to improve sleep. 35

Sleep apnea is a sleep disorder where a sleeper will experience apneas or pauses in breathing while sleeping. Sufferers of sleep apnea often snore loudly, stop breathing during the night many times, often wake up with a dry mouth and/or headache, are tired during the day, and have trouble focusing. The chances of sleep apnea are increased by being overweight, as fat around the upper airway can block the airway, especially when sleeping on the back.

- A 20-year review of children ages 6-17 years with obesity-associated diseases found that hospital discharges for sleep apnea increased 436%.

- 18 million adult Americans have sleep apnea.

- A 1999 study from the University of Chicago found that sleep debt accumulated over a few days can slow metabolism and disrupt hormone levels. 11 healthy young adults were restricted to 4-6 hours of sleep per night. Their ability to process sugar in the blood had reduced, in some cases, to the level of diabetics. 33

- The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study concluded that short sleep was associated with 15.5% lower leptin levels and 14.9% elevated grehlin levels. Leptin is the hormone that suppresses appetite, and ghrelin stimulates appetite, increased food intake, and promotes fat storage. 34

- Oregan State University researchers found that people who exercise 150 minutes per week slept better and felt more alert during the day compared to those who don't. 35

- Researchers Guglielmo Beccuti and Silvana Pannain explain that recent epidemiological and laboratory evidence confirms previous findings of an association between sleep loss and an increased risk of obesity. Sleep loss has been shown to result in decreased insulin sensitivity, increased evening levels of cortisol (the stress hormone that prevents sleep), increased levels of ghrelin (increasing appetite), and decreased levels of leptin (reducing the feeling of satiation). They further explain that the worldwide prevalence of obesity has doubled since 1980, and this epidemic has been paralleled by a trend of reduced sleep. 36

- A 6-year Italian study found that every extra hour of sleep decreased the incidence of obesity by 30%. 36

- Lack of sleep can negatively affect eating habits. One study found an increased caloric intake in 12 normal-weight healthy adults after 4 hours of sleep. 37

- Another study reported a 14% increase in caloric intake, especially for carbohydrates in 10 healthy adults who had slept 4.5 hours. 38

Anxiety Disorders & Sleep Statistics

Sleep issues are very common with people with anxiety disorders and depression. Some anxiety disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder have even included nightmares or insomnia in their definitions.

Anxiety usually functions as an alarm bell for potential danger, but in anxiety disorders the alarms may be intense, frequent, or even continuous. This level of arousal leads to issues with sleep.

- 24% to 36% of insomnia sufferers have an anxiety disorder, while 27% to 42% of those with hypersomnia have anxiety disorders. 40

- In another study, researchers found that insomnia appeared before the anxiety disorder in 18% of the subjects. 38.6% of the time, insomnia and the anxiety disorder appeared around the same time. 43.5% of the time, anxiety appeared before insomnia. 40

- In a study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, researchers found that 68% of subjects had difficulty falling asleep, while 77% had restless sleep. 41

Odds ratios for specific anxiety disorders associated with lifetime sleep disturbances (adapted from Breslau et al 39 ). 40

| Anxiety Disorder | Insomnia Alone | Hypersomnia Alone | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.0 (2.8-17.2) | 4.5 (1.5-15.3) | 4.8 (1.5-15.2) | |

| 5.3 (2.0-13.6) | 4.3 (1.3-14.8) | 8.5 (3.1-23.5) | |

| 5.4 (2.0-14.8) | 1.2 (0.1-9.7) | 13.1 (4.8-35.7) | |

| 1.5 (1.0-2.3) | 29 (1.8-4.8) | 4.0 (2.5-6.5) | |

| 2.4 (1.6-3.5)/td> | 3.3 (2.0-5.4) | 4.5 (2.8-3.7) |

- The majority of patients with panic disorder experience nocturnal panic attacks. Up to 18% of panic attacks happen while asleep. Ambulatory heart rate changes in patients with panic attacks. 42

- It's been estimated that 60% to 70% of patients had general anxiety disorder (GAD), suggesting that insomnia is one of the core facets of GAD. 43

- Sufferers of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) commonly complain of nightmares and insomnia. It's been estimated that 96% of Holocaust survivors had insomnia and 83% had recurrent nightmares. 44

- One study found that PTSD sufferers estimate that they lay awake more than half of the night. 45

Depression and poor sleep occur so commonly together that researchers aren't sure if one is causing the other or if they're just associated. Both insomnia and sleeping too much could be signs of depression.

- It's estimated that 75% of patients with depression also have insomnia. 46

- According to the National Sleep Foundation , those with insomnia have a 10 times greater risk of developing depression than those with enough restful sleep.

- According to the journal Lancet Psychiatry , people with mental health disorders showed improvement from the increased amount and quality of sleep.

- Night owls are more likely to be depressed compared to early birds, and researchers aren't sure why.

- A Japanese study from 2006 analyzed data from 24,686 people aged 20 and above and found that people who sleep less than 6 hours and more than 8 hours tend to be depressed, creating a U-shaped association with symptoms of depression. 47

- Jones, Jeffrey. (December 19, 2013). https://news.gallup.com/poll/166553/less-recommended-amount-sleep.aspx

- American Academy of Pediatrics Endorsement of Childhood Sleep Guidelines. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/American-Academy-of-Pediatrics-Supports-Childhood-Sleep-Guidelines.aspx

- Burgard SA, Ailshire JA. Gender and Time for Sleep among U.S. Adults. Am Sociol Rev . 2013;78(1):51-69. doi:10.1177/0003122412472048

- Dr. Jim Horne. " Who REALLY needs more sleep - men or women? One of Britain's leading sleep experts says he has the answer." Daily Mail, January 26, 2010. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-1246029/Who-REALLY-needs-sleep--men-women-One-Britains-leading-sleep-experts-says-answer.html

- TIME Mobility Poll, in cooperation with Qualcomm. August 2012. https://www.qualcomm.com/media/documents/files/time-mobility-poll-in-cooperation-with-qualcomm.pdf

- Sleep Deprivation Can Threaten Competent Decision-making. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. May 5, 2007. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/05/070501075246.htm

- Oxford University Press. https://academic.oup.com/journals

- Shift Work Sleep Disorder. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/12146-shift-work-sleep-disorder

- Gupta R, Das S, Gujar K, Mishra KK, Gaur N, Majid A. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Sleep Disorders. Indian J Psychiatry . 2017;59(Suppl 1):S116-S138. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.196978.

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, Roth T, Shahly V, Shillington AC, Stephenson JJ, Walsh JK. Insomnia and the performance of US workers: results from the America insomnia survey. Sleep . 2011 Sep 1;34(9):1161-71. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1230. Erratum in: Sleep. 2011;34(11):1608. Erratum in: Sleep. 2012 Jun;35(6):725.

- Kessler, R.C., Berglund, P.A., Coulouvrat, C., Hajak, G., Roth, T., Shahly, V., et al. (2011). "Insomnia and the performance of US workers: results from the America insomnia survey. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21886353 34(9): 1161-1171.

- Deirdre Conroy, PH.D. (June 13, 2016). https://healthblog.uofmhealth.org/health-management/3-reasons-women-are-more-likely-to-have-insomnia

- Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med . 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7-S10.

- Billiard M., Dauvilliers Y. Narcolepsy In: Billiard M, ed. Sleep: Physiology Investigations and Medicine. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 2003:403–406.

- Billiard M. Hypersomnias. In: Billiard M, ed. Sleep: Physiology Investigations and Medicine. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Guilleminault C, Tilkian A, Dement WC. The sleep apnea syndromes. Annu Rev Med. 1976;27:465-84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.27.020176.002341.

- Weaver TE, George CFP, “Cognition and Performance in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea,” in Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W (ed.), Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine (5th Edition), St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders, 2011, pages 1194-1205.

- Mindell JA, Owens JA. Diagnosis and Management of Sleep Problems. A Clinical Guide to Pediatric Sleep. Philadelphia. PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2003.

- Marcus CL. Pathophysiology of childhood obstructive sleep apnea: current concepts. Resp Physiol. 2000;119:143-154.

- Mansur A, Castillo PR, Rocha Cabrero F, et al. Restless Legs Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Apr 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430878/

- Thorpy MJ, Korman E, Spielman AJ, Glovinsky PB. Delayed sleep phase syndrome in adolescents. J Adolesc Health Care . 1988 Jan;9(1):22-7. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(88)90014-9

- Saxvig IW, Pallesen S, Wilhelmsen-Langeland A, Molde H, Bjorvatn B. Prevalence and correlates of delayed sleep phase in high school students. Sleep Med . 2012 Feb;13(2):193-9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.10.024.

- Paine SJ, Fink J, Gander PH, Warman GR. Identifying advanced and delayed sleep phase disorders in the general population: a national survey of New Zealand adults. Chronobiol Int. 2014 Jun;31(5):627-36. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2014.885036.

- Kurt S (December 2007). "IARC Monographs Programme finds cancer hazards associated with shiftwork, painting and firefighting" (Press release). International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- Lee ML, Howard ME, Horrey WJ, Liang Y, Anderson C, Shreeve MS, O'Brien CS, Czeisler CA. High risk of near-crash driving events following night-shift work. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2016 Jan 5;113(1):176-81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510383112.

- Division of Population Health. https://www.cdc.gov/NCCDPHP/dph/

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/

- Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al.; Consensus Conference Panel. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. Sleep . 2015;38:1161–1183.

- Zhang X, Holt JB, Lu H, et al. Multilevel regression and poststratification for small area estimation of population health outcomes: a case study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence using BRFSS. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(8):1025-1033.

- Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med . 2016;12(6):785–786.

- CDC - Data and Statistics. Short Sleep Duration Among US adults. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html

- Wheaton AG, Olsen EO, Miller GF, Croft JB. Sleep duration and injury-related risk behaviors among high school students — United States, 2007–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:337–341. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6513a1.htm

- "Sleep Health Index." SleepFoundation.org. 2018. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/shi

- Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med . 2004;1(3):e62. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062

- Godman, Heidi. "Losing Weight and Belly Fat Improves Sleep." Harvard Health Publishing, November 12, 2012, https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/losing-weight-and-belly-fat-improves-sleep-201211145531

- Beccuti G, Pannain S. Sleep and obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care . 2011;14(4):402-412. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283479109

- Brondel L, Romer MA, Nougues PM, Touyarou P, Davenne D. Acute partial sleep deprivation increases food intake in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Jun;91(6):1550-9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28523.

- Tasali E, Broussard J, Day A, et al. Sleep curtailment in healthy young adults is associated with increased ad lib food intake [meeting abstract]. Sleep . 2009; 32 (Suppl):A163.

- Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry . 1996 Mar 15;39(6):411-8. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3.

- Staner L. Sleep and anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci . 2003;5(3):249-258. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2003.5.3/lstaner.

- Sheehan DV, Ballenger J, Jacobsen G. Treatment of endogenous anxiety with phobic, hysterical, and hypochondriacal symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry . 1980 Jan;37(1):51-59. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780140053006.

- Taylor CB, Sheikh J, Agras WS, Roth WT, Margraf J, Ehlers A, Maddock RJ, Gossard D. Ambulatory heart rate changes in patients with panic attacks. Am J Psychiatry . 1986 Apr;143(4):478-82. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.4.478.

- Ohayon MM. Prevalence of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of insomnia: distinguishing insomnia related to mental disorders from sleep disorders. J Psychiatr Res . 1997; 31 :333–346.

- Kuch K, Cox BJ. Symptoms of PTSD in 124 survivors of the Holocaust. Am J Psychiatry. 1992 Mar;149(3):337-40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.3.337.

- Pillar G, Malhotra A, Lavie P. Post-traumatic stress disorder and sleep-what a nightmare! Sleep Med Rev. 2000 Apr;4(2):183-200. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0095.

- Nutt D, Wilson S, Paterson L. Sleep disorders as core symptoms of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci . 2008;10(3):329-336. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.3/dnutt

- Kaneita Y, Ohida T, Uchiyama M, Takemura S, Kawahara K, Yokoyama E, Miyake T, Harano S, Suzuki K, Fujita T. The relationship between depression and sleep disturbances: a Japanese nationwide general population survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;67(2):196-203. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0204.

Related Content

Does Exercise Improve Sleep?

Published: March 22, 2023

Omega-3s for Better Sleep

Published: July 12, 2023

Sleep Disorders

Sleep Needs by Age and Gender

Published: February 22, 2023

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Adult health

How many hours of sleep are enough for good health?

The amount of sleep you need depends on various factors — especially your age. While sleep needs vary significantly among individuals, consider these general guidelines for different age groups:

| Age group | Recommended amount of sleep |

|---|---|

| Infants 4 months to 12 months | 12 to 16 hours per 24 hours, including naps |

| 1 to 2 years | 11 to 14 hours per 24 hours, including naps |

| 3 to 5 years | 10 to 13 hours per 24 hours, including naps |

| 6 to 12 years | 9 to 12 hours per 24 hours |

| 13 to 18 years | 8 to 10 hours per 24 hours |

| Adults | 7 or more hours a night |

In addition to age, other factors can affect how many hours of sleep you need. For example:

- Sleep quality. If your sleep is frequently interrupted, you're not getting quality sleep. The quality of your sleep is just as important as the quantity.

- Previous sleep deprivation. If you're sleep deprived, the amount of sleep you need increases.

- Pregnancy. Changes in hormone levels and physical discomfort can result in poor sleep quality.

- Aging. Older adults need about the same amount of sleep as younger adults. As you get older, however, your sleeping patterns might change. Older adults tend to sleep more lightly, take longer to start sleeping and sleep for shorter time spans than do younger adults. Older adults also tend to wake up multiple times during the night.

For kids, getting the recommended amount of sleep on a regular basis is linked with better health, including improved attention, behavior, learning, memory, the ability to control emotions, quality of life, and mental and physical health.

For adults, getting less than seven hours of sleep a night on a regular basis has been linked with poor health, including weight gain, having a body mass index of 30 or higher, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, and depression.

If you're concerned about the amount of sleep you or your child is getting, talk to your doctor or your child's doctor.

Eric J. Olson, M.D.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Sleep and psoriatic arthritis

- Brain basics: Understanding sleep. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Understanding-Sleep. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- Paruthi S, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: A consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2016; doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5866.

- Landon MB, et al., eds. Maternal physiology. In: Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- Cirelli C. Insufficient sleep: Definition, epidemiology, and adverse outcomes. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- Kryger MH, et al., eds. Normal sleep. In: Atlas of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2014. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed March 31, 2021.

- Watson NF, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. 2015; doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4758.

- Alzheimer's sleep problems

- Can psoriasis make it hard to sleep?

- Hidradenitis suppurativa and sleep: How to get more zzz's

- I have atopic dermatitis. How can I sleep better?

- Lack of sleep: Can it make you sick?

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Meditation is good medicine

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Sleep Spoiler - Tips for a Good Night's Rest

- Melatonin side effects

- Napping do's and don'ts

- Prescription sleeping pills: What's right for you?

- Antihistamines for insomnia

- OTC sleep aids

- Sleeping positions that reduce back pain

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Expert Answers

- How many hours of sleep are enough

Help transform healthcare

Your donation can make a difference in the future of healthcare. Give now to support Mayo Clinic's research.

- ABOUT THE PROJECT

- ONGOING PROJECTS

- PUBLICATIONS

- SURVEY METHODS

- SPOTLIGHT ON:

- DRUGS AND ALCOHOL

- PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

- SEDENTARY BEHAVIOR

- SEE ALL FINDINGS

- WOMEN’S FINANCIAL SECURITY

- HOME OWNERSHIP

- EMERGENCY FUNDS

- HEALTH INSURANCE

- INVESTMENTS

- LIFE INSURANCE

- LONG TERM CARE

- VOLUNTEERISM

- CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

- RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS

- WORKING FOR PAY

- AFFILIATE INTERVIEWS

- DIRECTORS’ BLOG POSTS

- EXPERT PERSPECTIVES

- PERSONAL PERSPECTIVES

- STANFORD CENTER ON LONGEVITY >

- Research Update on Diet

- Research Update on Sleep

Research Update 1

By Marie Conley Smith

I n a world full of opportunities, stressors, inequalities, and distractions, maintaining a healthy lifestyle can be challenging, and sleep is often the first habit to suffer. Good sleep hygiene is a huge commitment: it takes up about a third of the day, every day, and works best when kept on a consistent schedule. It does not help that the primary short-term symptoms of insufficient sleep can be self-medicated away with caffeine. However, the effects of sleep loss can range from inconvenient to downright dangerous; people have trouble learning and being productive, take risks more readily, and are more likely to get into accidents. These effects also last longer than it takes to get them, as recovering from each night of poor sleep takes multiple days. When it comes to sleep, every night counts. In this update, we will discuss what Stanford researchers have to say about sleep and why we need it, who is getting too little of it, and some of the latest findings that may help us sleep better.

We have not cracked the code on sleep

Despite this progress, scientists have not been able to crack the code of why sleep is critical to brain function. There is also little consensus about how sleep stages actually affect quality of sleep and how they affect us when we are awake.

Part of the challenge of cracking the code on sleep is how difficult it is to study. The gold standard of sleep study, polysomnography, developed by Dement in the 1960s, 1 is the most reliable tool for measuring many sleep characteristics and detecting sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea and narcolepsy. However, it is expensive and time-consuming to run, which means that usually only a night or two is recorded. This snapshot of sleep may not reflect what normally occurs for a given person, and makes it difficult to draw conclusions about their behavior and performance in the days surrounding the sleep measurement.

The recent explosion in consumer wearable devices is a promising trend for researchers because of their potential to measure thousands of people’s sleep in their natural environments. They have not yet been widely adopted as measurement tools by scientists, however, as it is unclear if they provide the level of precision and measurement consistency required for a scientific study. Researchers at Stanford have called for these devices to be cleared by the FDA before using them to assign a diagnosis. 2 The “holy grail” would be a wearable device that could track sleep accurately while also providing performance information about the rest of the day, which would allow researchers to recognize more nuanced relationships between how people sleep and how it affects their lives.

The short- and long-term effects of insufficient sleep

We all know anecdotally what it is like to get too little sleep; it might be described with words and phrases like “tired,” “cranky,” “sluggish,” and “need caffeine.” Review of the scientific literature reveals how wide-ranging these effects can be. With too little sleep, people have a harder time learning 3 and concentrating, and are more likely to take risks. 4,5 The likelihood of getting into an auto accident increases. 6 Sleep deprivation has a bidirectional relationship with depression, 7,8 in that insomnia often both precedes and follows a depressive episode. Short sleep also interferes with other Healthy Living behaviors: people are more likely to crave sweet and fatty foods 9 and to choose foods that are calorically dense, 10 are more prone to injury during exercise, 11 and have an increased risk of obesity. 12

Sleep deprivation can even affect mundane daily activities. In 2017, then Stanford PhD candidate Tim Althoff and Professor Jamie Zeitzer of the Stanford Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine took up the sleep measurement challenge by collaborating with Microsoft Research to examine the effects of sleep deprivation through a common daily activity: using an online search engine. 13 They paired users’ Microsoft Band sleep data with their Bing searches among users who had agreed to share their activity for study. By linking quantity and timing of sleep with typing speed during the searches, they were able to draw a number of conclusions about how sleep quality affects performance.

In this study, the researchers captured the sleep duration and search engine interactions of over 31,000 people. The researchers measured the amount of time between keystrokes as people typed their search engine entries, and used this as a measure of daily performance (that is, how well people did after a night of sleep). They were able to track the people who had multiple nights of insufficient sleep (defined as 6 hours of sleep or fewer) to see if their typing speed changed. They found that, on average, one night of insufficient sleep resulted in worse performance for three days, and two nights of insufficient sleep negatively impacted performance for six days. In other words, it took people almost an entire week to recover their performance after two consecutive nights of insufficient sleep. The implication is that the impact of sleep loss can persist for days.

Recent Stanford solutions for better sleep

Ongoing research at Stanford has led both to treatments for sleep disorders and to recommendations for best sleep practices for the public.

There are a few clinics and organizations that offer CBTI remotely in an effort to give more people access. There are apps such as SleepRate , which features content designed by Stanford researchers, Somryst , which was recently approved by the FDA, and Sleepio , which is offered by several large employers as an employee benefit. The Cleveland Sleep Clinic offers a 6-week online program called “ Go! to Sleep ,” and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs offers one of the same duration called “ Path to Better Sleep .” A physician should be consulted before starting any of these programs to ensure there are not any underlying disorders that need to be addressed.

Ultrashort light flash therapy Professor Jamie Zeitzer was interested in helping people who had a hard time sleeping because their circadian rhythm was not in sync with their desired sleep schedule. He discovered that ultrashort bursts of light directed into a person’s closed eyes while they were sleeping was very effective at shifting the time a person starts getting sleepy. Sleep doctors had already been using continuous light to help people reset their internal clock while they were awake; this new short-flash method shows great promise not only because of its effectiveness, but because it can be administered passively while people are sleeping. The approach involves wearing a sleep mask that emits the bright flashes and has been shown to only wake individuals who are particularly sensitive to light.

Lumos Sleep Mask

Professor Zeitzer and his team administered these ultrashort light flashes to teenagers, whose natural circadian systems have shifted so that their sleep and wake times are considerably later than children or adults. The time structure of our society, and schools in particular, does not take this into account. Professor Zeitzer administered the light flashes to see if it would help teens go to bed earlier. 20 They found that, while the teenagers were getting sleepy earlier, the light flashes alone were not enough to get the teenagers to bed earlier. With a second group of teens, they combined the light therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) sessions. The CBT sessions served to inform the teens about sleep health and hygiene and helped them schedule their activities to allow for their desired sleep hours. After this combined therapy trial, the teens went to bed an average of 50 minutes earlier, getting an average of 43 more minutes of sleep per night. The researchers found the CBT component to be integral to behavior change – without the added education and support, the teens were not motivated enough to change their behavior and would simply push past their sleepiness.

This ultrashort light flash therapy can be used by anyone who may want to shift their sleep schedule; for example, to rebound from jet lag or to cope with a consistent graveyard shift at work. There is no evidence that other groups would require accompanying CBT like the teens, as long as they are self-motivated to change their sleep schedule. Zeitzer plans to test this technology next with older adults who wish to push their sleep time later. A company has spun out of this work, which Zeitzer advises but in which he has no financial interest, called Lumos . They are currently developing their product, and are hoping to make this intervention widely available.

Data Spotlight on: Black Americans

While most Americans have seen improvements in sleep over the past decade, Black Americans continue to sleep significantly less than other groups. This trend has been examined both by researchers and the popular press. 21,22 Researchers have found that Black Americans, in addition to getting shorter sleep, are also more likely to get poor quality sleep – spending less time in the most restorative stages of sleep 23,24 – and to develop obstructive sleep apnea. 25 Black Americans are also disproportionately affected by diseases that have been associated with poor sleep, such as obesity, diabetes, 26 and cardiovascular disease. 25

The exact reason(s) for Black Americans’ poor sleep is still unclear, though researchers have proposed potential contributing factors, largely related to the social inequality Black Americans face in the U.S.:

Experiences of discrimination : the stress of racial discrimination has been associated with spending lesstime in deep sleep and more time in light sleep among Black Americans. 24

Living environment : neighborhood quality has been linked to sleep quality, 27 and Stanford researchersfound that racial and income disparities persist in neighborhoods. 28 They found that while middle-income white families are more likely to live in resource-rich neighborhoods with other middle-income families, middle-income black families tend to live in markedly lower-income, resource-poorneighborhoods.

Work and income inequality : for example, shift work can cause irregular working hours. This leadspeople to suffer “social jetlag,”; a discrepancy in sleep hours between work and free days, 29 leading tosymptoms of sleep deprivation.

Lack of access to resources : particularly sleep-related healthcare and education.

Some of these factors are being addressed directly. Professor Girardin Jean-Louis from New York University and his team have devoted themselves to addressing the access to healthcare and education issue among local black communities in New York by tailoring online materials about obstructive sleep apnea to the culture, language, and barriers of specific communities. 30 Professor Jamie Zeitzer and his team at Stanford recently completed an initial clinical trial of a drug (suvorexant), which was found to help people who work at night get three more hours of sleep during the day. 31 Professor Zeitzer’s ultrashort light flash therapy (discussed above) may also help with shift work. These interventions could help to improve sleep for Black Americans, but they may not make up the whole picture; it could be that the underlying social inequality needs to be addressed in order to fully close the sleep gap.

Thanks to Jamie Zeitzer and Ken Smith for their insights and edits on this report.

- Deak, M., & Epstein, L. J. (2009). The history of polysomnography. Sleep Medicine Clinics , 4 (3), 313–321.

- Cheung, J., Zeitzer, J. M., Lu, H., & Mignot, E. (2018). Validation of minute-to-minute scoring for sleep and wake periods in a consumer wearable device compared to an actigraphy device. Sleep Science and Practice , 2 (1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-018-0029-8

- Gao, C., Terlizzese, T., & Scullin, M. K. (2019). Short sleep and late bedtimes are detrimental to educational learning and knowledge transfer: An investigation of individual differences in susceptibility. Chronobiology International , 36 (3), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2018.1539401

- O’Brien, E. M., & Mindell, J. A. (2005). Sleep and risk-taking behavior in adolescents. Behavioral Sleep Medicine , 3 (3), 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15402010bsm0303_1

- Rusnac, N., Spitzenstetter, F., & Tassi, P. (2019). Chronic sleep loss and risk-taking behavior: Does the origin of sleep loss matter? Behavioral Sleep Medicine , 17 (6), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2018.1483368

- Bioulac, S., Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A., Arnaud, M., Sagaspe, P., Moore, N., Salvo, F., & Philip, P. (2017). Risk of motor vehicle accidents related to sleepiness at the wheel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep , 40 (10). https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx134

- Franzen, P. L., & Buysse, D. J. (2008). Sleep disturbances and depression: Risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience , 10 (4), 473–481.

- Tsuno, N., & Ritchie, K. (2005). Sleep and Depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry , 16.

- Lv, W., Finlayson, G., & Dando, R. (2018). Sleep, food cravings and taste. Appetite , 125 , 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.013

- Pardi, D., Buman, M., Black, J., Lammers, G. J., & Zeitzer, J. M. (2017). Eating decisions based on alertness levels after a single night of sleep manipulation: A randomized clinical trial. Sleep , 40 (2). https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsw039

- Chennaoui, M., Arnal, P. J., Sauvet, F., & Léger, D. (2015). Sleep and exercise: A reciprocal issue? Sleep Medicine Reviews , 20 , 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.008

- Cappuccio, F. P., Taggart, F. M., Kandala, N. B., Currie, A., Peile, E., Stranges, S., & Miller, M. A. (2008). Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep , 31 (5), 619-626.

- Althoff, T., Horvitz, E., White, R. W., & Zeitzer, J. (2017, April). Harnessing the web for population-scale physiological sensing: A case study of sleep and performance. In Proceedings of the 26th international conference on World Wide Web (pp. 113-122).

- Roth, T. (2007). Insomnia: Definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine , 3 (5 Suppl), S7–S10.

- Qaseem, A., Kansagara, D., Forciea, M. A., Cooke, M., & Denberg, T. D. (2016). Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine , 165 (2), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2175

- Jacobs, G. D., Pace-Schott, E. F., Stickgold, R., & Otto, M. W. (2004). Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia: A randomized controlled trial and direct comparison. Archives of Internal Medicine , 164 (17), 1888–1896. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.17.1888

- Manber, R., Bei, B., Simpson, N., Asarnow, L., Rangel, E., Sit, A., & Lyell, D. (2019). Cognitive behavioral therapy for prenatal insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology , 133 (5), 911–919. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003216

- Ong, J. C., Crawford, M. R., Dawson, S. C., Fogg, L. F., Turner, A. D., Wyatt, J. K., Crisostomo, M. I., Chhangani, B. S., Kushida, C. A., Edinger, J. D., Abbott, S. M., Malkani, R. G., Attarian, H. P., & Zee, P. C. (2020). A randomized controlled trial of CBT-I and PAP for obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid insomnia: Main outcomes from the MATRICS study. Sleep . https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsaa041

- Karlin, B. E., Trockel, M., Taylor, C. B., Gimeno, J., & Manber, R. (20130415). National dissemination of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in veterans: Therapist- and patient-level outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 81 (5), 912. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032554

- Kaplan, K. A., Mashash, M., Williams, R., Batchelder, H., Starr-Glass, L., & Zeitzer, J. M. (2019). Effect of light flashes vs sham therapy during sleep with adjunct cognitive behavioral therapy on sleep quality among adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open , 2 (9), e1911944. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11944

- Resnick, B. (2015, October 27). The Racial Inequality of Sleep . The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/the-sleep-gap-and-racial-inequality/412405/

- Resnick, B., & Barton, G. (2018, April 12). Black Americans don’t sleep as well as white Americans. That’s a problem. Vox. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/4/12/17224328/sleep-gap-black-white-minority-america-health-consequences

- Beatty, D. L., Hall, M. H., Kamarck, T. A., Buysse, D. J., Owens, J. F., Reis, S. E., Mezick, E. J., Strollo, P. J., & Matthews, K. A. (2011). Unfair treatment is associated with poor sleep in African American and Caucasian adults: Pittsburgh SleepSCORE project. Health Psychology , 30 (3), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022976

- Tomfohr, L., Pung, M. A., Edwards, K. M., & Dimsdale, J. E. (2012). Racial differences in sleep architecture: The role of ethnic discrimination. Biological Psychology , 89 (1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.09.002

- Olafiranye, O., Akinboboye, O., Mitchell, J., Ogedegbe, G., & Jean-Louis, G. (2013). Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease in blacks: A call to action from association of black cardiologists. American Heart Journal , 165 (4), 468–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2012.12.018

- Jackson, C. L., Redline, S., Kawachi, I., & Hu, F. B. (2013). Association between sleep duration and diabetes in black and white adults. Diabetes Care , 36 (11), 3557–3565. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0777

- Hale, L., Hill, T. D., & Burdette, A. M. (2010). Does sleep quality mediate the association between neighborhood disorder and self-rated physical health? Preventive Medicine , 51 (3–4), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.017

- Reardon, S. F., Fox, L., & Townsend, J. (2015). Neighborhood income composition by household race and income, 1990–2009. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 660 (1), 78–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215576104

- Wittmann, M., Dinich, J., Merrow, M., & Roenneberg, T. (2006). Social jetlag: Misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiology International , 23 (1–2), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420520500545979

- Jean-Louis, G., Robbins, R., Williams, N. J., Allegrante, J. P., Rapoport, D. M., Cohall, A., & Ogedegbe, G. (2020). Tailored Approach to Sleep Health Education (TASHE): A randomized controlled trial of a web-based application. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine . https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8510

- Zeitzer, J. M., Joyce, D. S., McBean, A., Quevedo, Y. L., Hernandez, B., & Holty, J.-E. (2020). Effect of suvorexant vs placebo on total daytime sleep hours in shift workers: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open , 3 (6), e206614. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6614

News & Articles

How much sleep do you really need.

October 1, 2020 / Sleep and You

Getting enough sleep is doable and important for your health. Read on for how many hours to strive for at every age.

Sleep is essential to feeling rested and alert. Getting the right amount for your mind and body feels great and helps you wake up feeling refreshed and ready to go. Every person is different when it comes to the exact amount of sleep that’s optimal for them, but most people fall within a range, depending on their age. These guidelines can help you determine how much sleep you really need, while providing some easy ways to achieve it.

How Many Hours of Sleep Do You Need?

There is no precise number of minutes or hours of sleep at night that guarantees you will wake up feeling totally refreshed. But based on your age and lifestyle, what’s recommended for you likely falls within a certain range. To help yourself stay alert during the day, try sticking with these guidelines.

Newborns: From 0-3 months, babies need between 14 and 17 hours of sleep. This includes daytime naps, since newborns rarely sleep through the night. Older infants (4-11 months) need about 12 to 15 hours of sleep each day.

Toddlers: Between the first and second year of life, toddlers need between 11 and 14 hours of sleep each night.

Children: Preschoolers (3-5 years) should get 10 to 13 hours, while school-age kids (6-13 years) should strive for nine to 11 hours each night.

Teenagers: As kids get older, their need for sleep decreases slightly. Teens (14-17 years) require about eight to 10 hours of nightly sleep.

Adults: Between the ages of 18 and 64, adults should aim for seven to nine hours of nightly sleep. If you’re older than 65, you may need a little less: seven to eight hours is recommended.

Build in Some Flex Time

Some people can function well on the lower end of the range and others will need every minute of the upper limit. In fact, an additional hour or two on either side of a given range may be appropriate, depending on the person. Still, straying too far from the recommended amount could lead to a variety of health issues. For example, shortchanging sleep has been associated with weight gain, reduced immunity, high blood pressure, and depression.

The negative effects of too little or too much sleep aren’t just physical—they can also interfere with your mental health. Your outlook, mood, and attention span all depend on getting the right amount of sleep, and without it, your job performance (not to mention your personal life) can suffer.

Easy Ways to Get More Sleep

If getting enough sleep seems like an uphill battle, there are a few tips you can try. To start, head to bed at the same time every night, to allow your body to settle into a regular sleep-wake schedule. Just the way kids benefit from a set schedule, adults who stick to a regular pre-sleep routine that includes reading, meditation, journaling, and a warm bath may find it easier to wind down in the evening.

To help get quality sleep, avoid alcohol, caffeine, and spicy and fried foods right before bedtime. Aim for a bedroom temperature between 60 and 67 °F , make sure it’s dark, and block any bothersome noises with a pair of earplugs. For a fuller list of sleep tips, read them here .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Curr Health Sci J

- v.43(1); Jan-Mar 2017

Research on Sleep Quality and the Factors Affecting the Sleep Quality of the Nursing Students

1 Uludag University Faculty of Health Sciences, Bursa, Turkey

F. TANRIKULU

2 Sakarya University Faculty of Health Sciences, Sakarya, Turkey

Purpose: This research has been conducted in order to examine the quality of sleep and the factors affecting the sleep quality.Material/Methods: The sample of this descriptive research is comprised of 223 volunteer students studying at Uludağ University Faculty of Health Sciences Department of Nursing. Research datas have been collected through personal features survey and Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index(PSQI). Results: The average result derived from the sample is 6.52±3.17. To briefly explain the average of the component scores: subjective sleep quality 1.29±0.76, sleep latency 1,55±0.94, sleep duration 0.78±0.99, habitual sleep activity 0.47±0.90, sleep disturbances 0.99±0.09, use of sleeping medication 0.12±0.48, daytime dysfunction 1.29±0.90. It has been observed that there is a meaningful discrepancies between average PSQI results and smoking habits of the students, total daily sleeping hours, efficient waking up times, average daily coffee consumption(p<0.05). According to the analyses there is no meaningful discrepancies between the age,gender, where the students live,snoozing during the morning classes, the existence of chronic diseases and daily average tea consumption.(p>0.05)Conclusions: According to the findings in the light of this research; nursing students have low sleep quality.

Introduction

Sleep, which is directly related to health and quality of life, is a basic need for a human being to continue his bio-psycho-social and cultural functions [ 1 ]. Sleep affects the quality of life and health,which is also perceived as an important variable[ 2 , 3 ]. Feeling energetic and fit after sleeping is descriped as the sleep quality [ 4 ]. The fact that, nowadays the complaints about sleep disorder being prevalent, low sleep quality being an indicator of many medical diseases and there is strong relationship between physical ,psychological wellness and sleep; sleep quality is an important concept in the clinic practices and related researches on sleep [ 5 ].

Sleeping disorders is a common health problem among adolescants and young adults [ 6 ]. There is a general belief that university students do not sleep enough [ 7 ]. It has been reported that the the amount and the quality of the sleep of university students has been changed in past few decades and the sleep disorders has been inclined [ 8 ]. In the related researches is found that sleeping disorder among university students in various frequencies and amounts [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Low quality of sleep harms not only the academic success but also behavioral and emotional problems [ 12 ], negative emotional status, increase in alcohol and smoking habits[ 13 , 14 ]. In another research, it has been found that, there is a link between sleep quality and pschological wellbeing; more psychological diseases are observed among university students with low sleep quality [ 15 ]. Additionally it is recorded in the medical literature that, sleep quality is affected from the external factors such as gender, academic success, academic background, general health, socio-economic status and the stress level of the person [ 1 , 4 , 7 , 16 ].