8 Communication Models: Understanding What They Are and How They Work

Every day we communicate with one another, so we all understand how communication takes place, right?

Actually, not always.

To understand how we communicate, communication theorists have developed models that illustrate how communication plays out.

In a way, as the US communication theorist Harold D. Lasswell said, the theorists’ task is to answer the question “Who says what to whom with what effect?” .

So, in this guide, we will:

- Introduce you to the models of communication that are most frequently encountered in the literature,

- Explain how these models help with workplace communication, and

- Dive deep into major models of communication and explain them in detail.

Without further ado, let’s begin!

Table of Contents

What are communication models?

According to Denis McQuail’s book Mass Communication Theory , “a model is a selective representation in verbal or diagrammatic form of some aspect of the dynamic process of mass communication.”

In other words, models of communication provide us with a visual representation of the different aspects of a communication situation .

Since communication is a complex process, it’s often challenging to determine where a conversation begins and ends.

That is where models of communication come in — to simplify the process of understanding communication .

Some models are more detailed than others, but even the most elaborate ones cannot perfectly represent what goes on in a communication encounter.

How can communication models help with work communication?

Since communication is the lifeblood of any organization , we have to strive to understand how it works.

Understanding communication models can help us:

- Think about our communication situations more deliberately ,

- Learn from our previous experiences , and

- Better prepare for future communication situations .

Do you remember the last time you had a misunderstanding with a colleague?

Was the workplace miscommunication caused by a wrongly interpreted tone of a message?

Or, maybe the email you had sent to your coworker ended up in the spam folder, so they didn’t even get it?

Whatever the misunderstanding was, we have to come to terms with the fact that some communication encounters are successful, others not so much.

That is why we have so many current communication models we can utilize to plan successful communication situations .

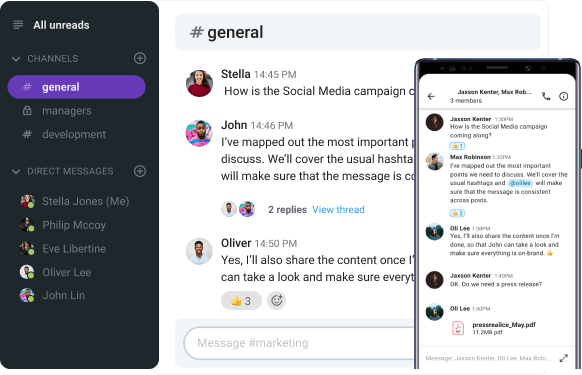

Free business communication tool

Secure, real-time communication for professionals.

FREE FOREVER • UNLIMITED COMMUNICATION

Now that we have seen what communication models are and why they are important for our workplace communication, it is time we take a closer look at the 8 models of communication.

8 Major communication models

There are 8 major models of communication, which can be divided into 3 categories:

- Aristotle’s communication model,

- Lasswell’s communication model,

- The Shannon-Weaver communication model, and

- Berlo’s S-M-C-R communication model.

- The Osgood-Schramm communication model, and

- The Westley and Maclean communication model.

- Barnlund’s transactional communication model, and

- Dance’s Helical communication model.

In the following paragraphs, we will analyze each of these models in detail, starting with linear models.

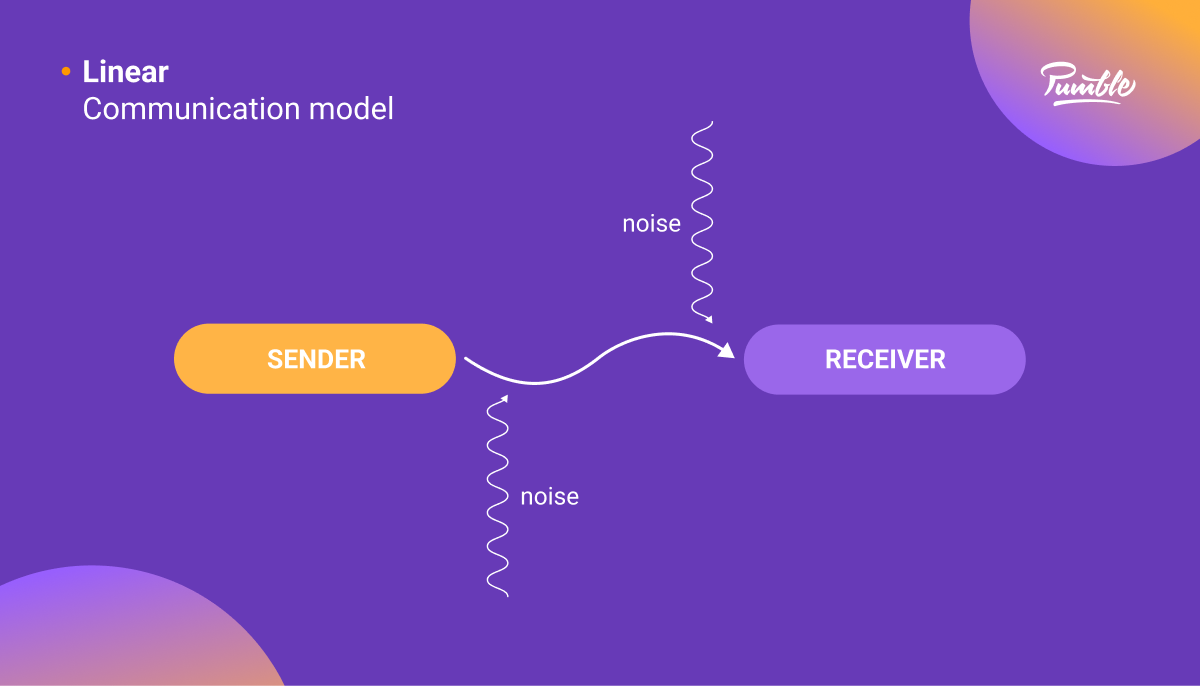

Linear models of communication

The linear communication model is straightforward and used mainly in marketing, sales, and PR, in communication with customers.

What is a linear model of communication?

Linear communication models suggest that communication takes place only in one direction .

The main elements in these models are:

- The channel ,

- The sender , and

- The receiver .

Some linear models of communication also mention noise as one of the factors that have a role in the communication process. Noise acts as the added (background) element that usually distracts from the original message.

But, we’ll talk more about the role of noise in the communication process later on. For now, let’s start with the basic elements of the linear communication model.

As illustrated in the linear communication model diagram below, this communication model is pretty straightforward.

Simply put, the sender transmits the message via a channel.

The channel, as the medium, changes the message into speech, writing, or animation.

The message then finally reaches the receiver, who decodes it.

We already mentioned the 3 most prominent linear models of communication, and now it is time to analyze each one of them in more detail.

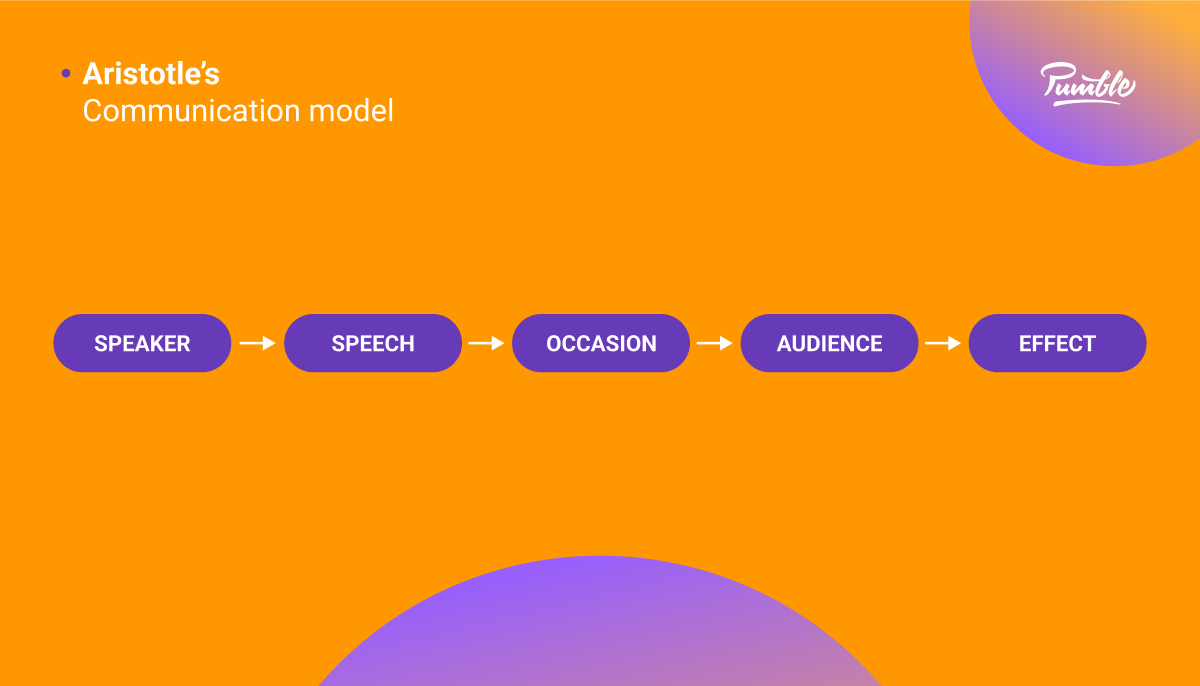

1. Aristotle’s model of communication

The oldest communication model that dates back to 300 BC, Aristotle’s model was designed to examine how to become a better and more persuasive communicator .

What is Aristotle’s model of communication?

Aristotle’s model of communication primarily focuses on the sender (public speaker, professor, etc.) who passes on their message to the receiver (the audience).

The sender is also the only active member in this model, whereas the audience is passive. This makes Aristotle’s communication model a foolproof way to excel in public speaking, seminars, and lectures.

What are the main elements of Aristotle’s communication model?

Aristotle identified 3 elements that improve communication within this model:

- Ethos — Defines the credibility of the speaker. Speaker gains credibility, authority, and power by being an expert in a field of their choice.

- Pathos — Connects the speaker with the audience through different emotions (anger, sadness, happiness, etc.)

- Logos — Signifies logic. Namely, it is not enough for the speech to be interesting — it needs to follow the rules of logic.

As shown in Aristotle’s communication model diagram below, Aristotle also suggested that we look at 5 components of a communication situation to analyze the best way to communicate:

- Speaker ,

- Speech ,

- Occasion ,

- Target audience , and

- Effect .

Aristotle’s communication model example

Picture this:

Professor Hustvedt is giving a lecture on neurological disorders to her students.

She delivers her speech persuasively, in a manner that leaves her students mesmerized.

The professor is at the center of attention, whereas her audience — her students — are merely passive listeners. Nevertheless, her message influences them and makes them act accordingly.

So, in this situation, professor Hustvedt is the speaker , and her lecture on disorders is the act of speech .

The occasion in question is a university lecture, while the students are her target audience .

The effect of her speech is the students gaining knowledge on this subject matter.

One of the major drawbacks of this model is that it does not pay attention to the feedback in communication because the audience is passive.

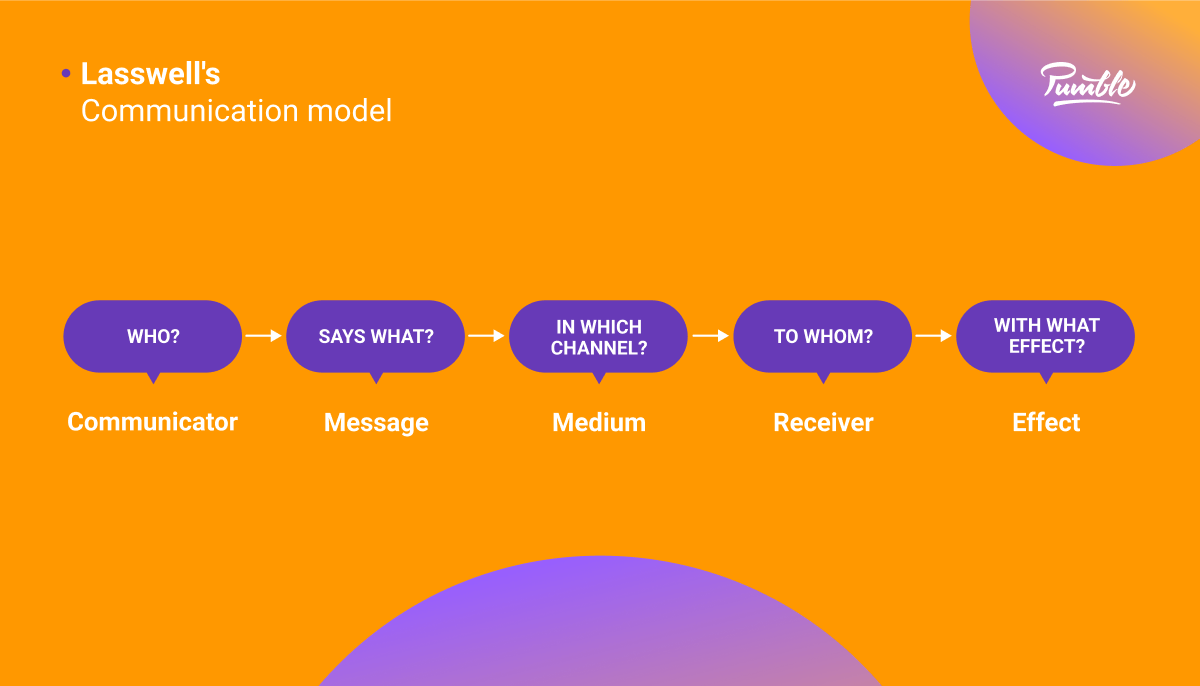

2. Lasswell’s model of communication

The next linear model on our list is Lasswell’s Model of mass communication.

What is Lasswell’s model of communication?

Lasswell’s communication model views communication as the transmission of a message with the effect as the result.

The effect in this case is the measurable and obvious change in the receiver of the message that is caused by the elements of communication.

If any of the elements change, the effect also changes.

What are the main elements of Lasswell’s communication model?

Lasswell’s model aims to answer the following 5 questions regarding its elements:

- Who created the message?

- What did they say?

- What channel did they use (TV, radio, blog)?

- To whom did they say it?

- What effect did it have on the receiver?

The answers to these questions offer us the main components of this model:

- Communicator ,

- Audience/Receiver , and

- Effect .

If we take a look at Lasswell’s communication model diagram below, we can get a better understanding of how these main components are organized.

Lasswell’s communication model example

Let’s say you are watching an infomercial channel on TV and on comes a suitcase salesman, Mr. Sanders.

He is promoting his brand of suitcases as the best. Aware that millions of viewers are watching his presentation, Mr. Sanders is determined to leave a remarkable impression.

By doing so, he is achieving brand awareness, promoting his product as the best on the market, and consequently increasing sales revenue.

So, in this instance, Mr. Sanders is the communicator .

The message he is conveying is the promotion of his brand of suitcases as the best.

The medium he uses is television.

His audience consists of evening TV viewers in the US.

The effect he is achieving by doing this is raising brand awareness and increasing sales revenue.

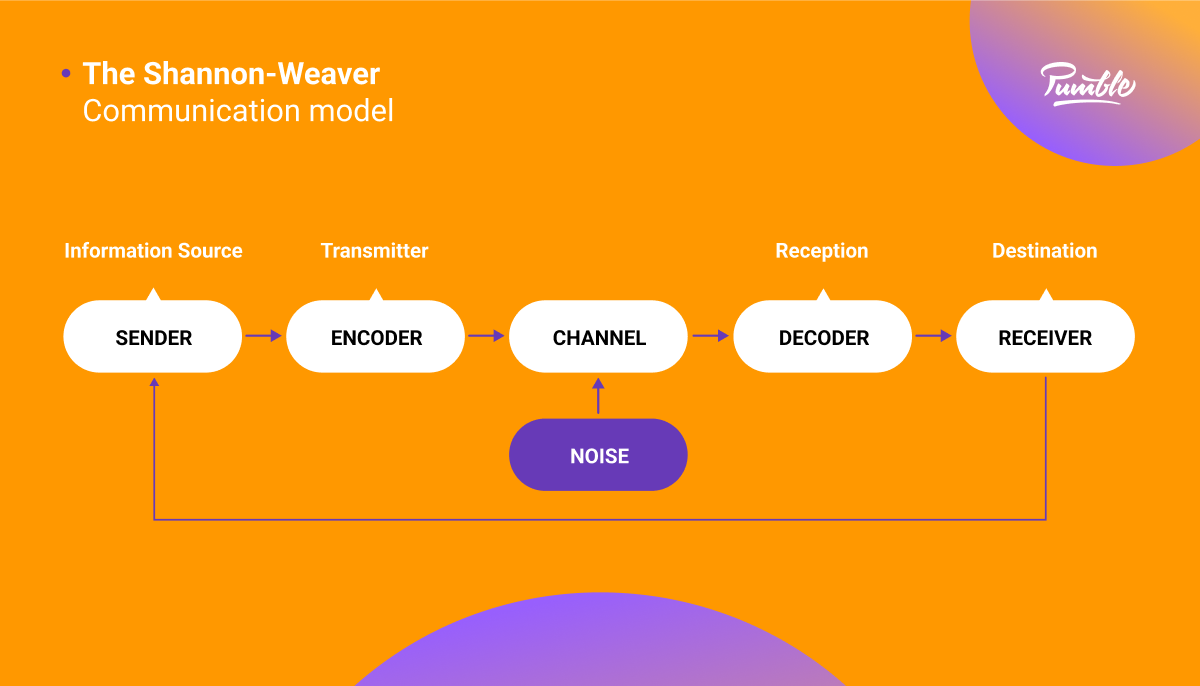

3. The Shannon-Weaver model of communication

Maybe the most popular model of communication is the Shannon-Weaver model.

Strangely enough, Shannon and Weaver were mathematicians, who developed their work during the Second World War in the Bell Telephone Laboratories. They aimed to discover which channels are most effective for communicating.

So, although they were doing research as part of their engineering endeavors, they claimed that their theory is applicable to human communication as well.

And, they were right.

What is the Shannon-Weaver model of communication?

The Shannon-Weaver communication model, therefore, is a mathematical communication concept that proposes that communication is a linear, one-way process that can be broken down into 5 key concepts.

What are the main elements of the Shannon-Weaver communication model?

As the Shanon-Weaver communication model diagram below shows, the main components of this model are:

- Decoder , and

- Receiver .

Shannon and Weaver were also the first to introduce the role of noise in the communication process. In his book Introduction to Communication Studies , John Fiske defines noise as:

“Anything that is added to the signal between its transmission and reception that is not intended by the source.”

The noise appears in the form of mishearing a conversation, misspelling an email, or static on a radio broadcast.

The Shannon-Weaver communication model example

Paula, a VP of Marketing in a multinational company, is briefing Julian on new marketing strategies they are about to introduce next month.

She wants a detailed study of the competitor’s activity by the end of the week.

Unfortunately, while she was speaking, her assistant Peter interrupted her, and she forgot to tell Julian about the most important issue.

At the end of the week, Julian did finish the report, but there were some mistakes, which had to be corrected later on.

Let’s take a moment to briefly analyze this example.

Paula is the sender , her mouth being the encoder .

The meeting she held was the channel .

Julian’s ears and brain were decoders , and Julian was the receiver .

Can you guess Peter’s role?

Yes, he was the noise .

The trouble in this process was the lack of feedback. Had Julian asked Paula for clarification after Peter interrupted her, the whole communication process would have been more effective, and there would have been no mistakes.

Updated version of the Shannon-Weaver communication model

Since the original version didn’t include it, the principle of feedback was added to the updated version, so the model provided a more truthful representation of human interaction.

The concept of feedback was derived from the studies of Norbert Wiener , the so-called father of cybernetics.

Simply put, feedback is the transfer of the receiver’s reaction back to the sender .

It allows the speaker to modify their performance according to the reaction of the audience.

Maybe the most important function of feedback is the fact that it helps the receiver feel involved in the communication process.

That makes the receiver more receptive to the message because they feel their opinion is being taken into account.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

In addition to being an important element in this communication model, feedback is also an integral part of effective workplace communication. To find out more about why it’s essential and how to practice it in the workplace, take a look at our resources:

- How to give constructive feedback when working remotely

- How to ask your manager for feedback

- Feedback vs feedforward: Moving from feedback to feedforward

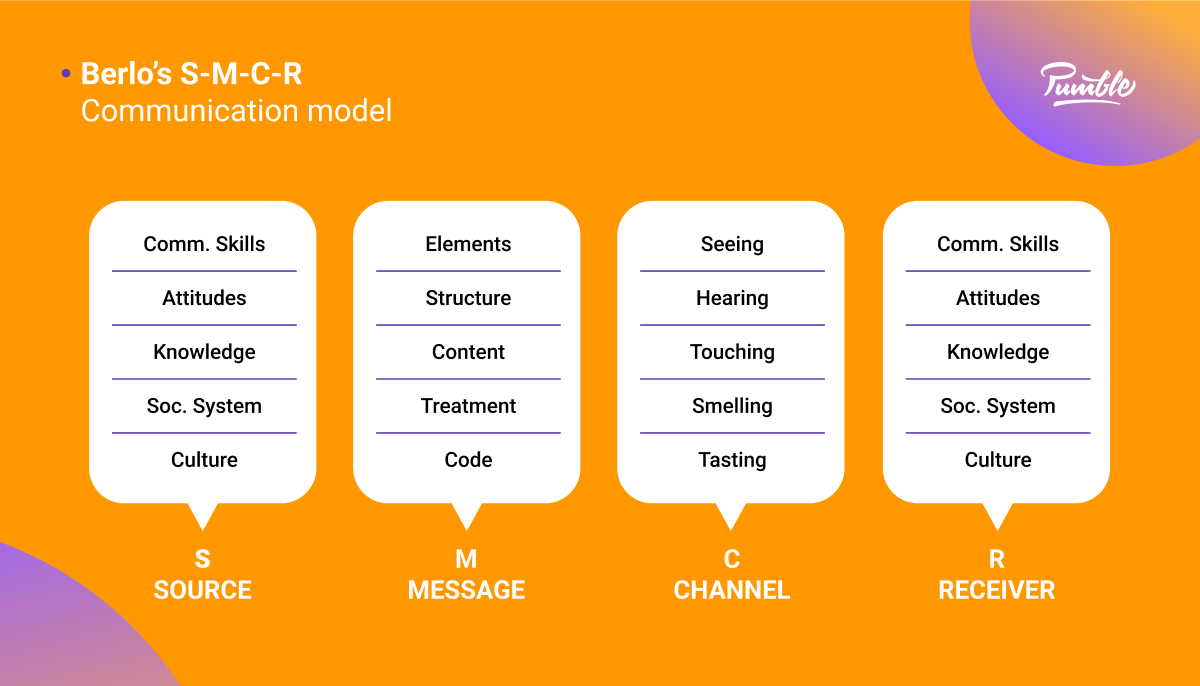

4. Berlo’s S-M-C-R model of communication

Berlo’s model of communication was first defined by David Berlo in his 1960 book The Process of Communication .

This communication model is unique in the sense that it gives a detailed account of the key elements in each step.

What is Berlo’s S-M-C-R model of communication?

Simply put, Berlo’s S-M-C-R communication model is a linear model of communication that suggests communication is the transfer of information between 4 basic steps or key elements.

What are the main elements of Berlo’s Berlo’s S-M-C-R communication model?

As shown in Berlo’s S-M-C-R communication model diagram below, these steps are the following:

- Source ,

- Channel , and

Let’s consider the key elements that affect how well the message is communicated, starting with the source.

Step #1: The source

The source or the sender carefully puts their thoughts into words and transfers the message to the receiver.

So, how does the sender transfer the information to the receiver according to Berlo’s S-M-C-R communication model?

With the help of:

- Communication skills — First and foremost, the source needs good communication skills to ensure the communication will be effective . The speaker should know when to pause, what to repeat, how to pronounce a word, etc.

- Attitude — Secondly, the source needs the right attitude. Without it, not even a great speaker would ever emerge as a winner. The source needs to make a lasting impression on the receiver(s).

- Knowledge — Here, knowledge does not refer to educational qualifications but to the clarity of the information that the source wants to transfer to the receiver.

- Social system — The source should be familiar with the social system in which the communication process takes place. That would help the source not to offend anyone.

- Culture — Last but not least, to achieve effective communication , the source needs to be acquainted with the culture in which the communication encounter is taking place. This is especially important for cross-cultural communication .

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

For more on how to improve cross-cultural communication and adapt to the global workforce, learn all about cultural intelligence and how to improve it in our blog post:

- Cultural intelligence: Definition, importance, and tips

Step #2: The message

The speaker creates the message when they transform their thoughts into words.

Here are the key factors of the message:

- Content — Simply put, this is the script of the conversation.

- Elements — Speech alone is not enough for the message to be fully understood. That is why other elements have to be taken into account: gestures, body language, facial expressions, etc.

- Treatment — The way the source treats the message. They have to be aware of the importance of the message so that they can convey it appropriately.

- Structure — The source has to properly structure the message to ensure the receiver will understand it correctly.

- Code — All the elements, verbal and nonverbal, need to be accurate if you do not want your message to get distorted and misinterpreted.

Step #3: The channel

To get from the source to the receiver, the message goes through the channel .

Berlo’s S-M-C-R communication model identifies all our senses are the channels that help us communicate with one another.

Our sense of hearing lets us know that someone is speaking to us.

Through our sense of taste , we gather information about the spiciness of a sauce we are eating.

Our sense of sight allows us to decipher traffic signs while driving.

We decide whether we like a certain perfume or not by smelling it.

By touching the water we feel whether it is too cold for a swim.

Step #4: The receiver

A receiver is a person the source is speaking to — the destination of the conveyed message.

To understand the message, the receiver should involve the same elements as the source. They should have similar communication skills, attitudes, and knowledge, and be acquainted with the social system and culture in which they communicate.

Berlo’s S-M-C-R communication model example

Watching the news on television is the perfect example of Berlo’s S-M-C-R Model of communication.

In this case, the news presenter is the source of the news and they convey the message to the audience.

The news is the message, the television is the channel, and the audience are the receivers of the message.

Now that we have become acquainted with linear models of communication, it is time we move on to something a little more complex and dynamic — interactive models of communication.

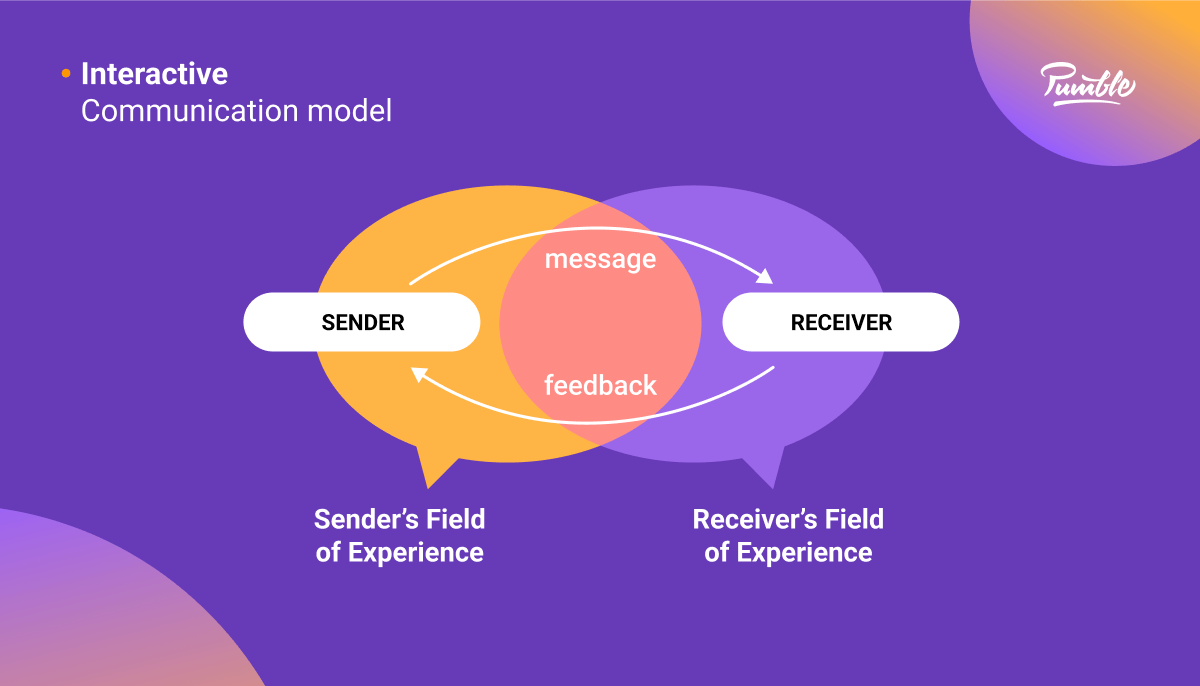

Interactive models of communication

Interactive models are used in internet-based and mediated communication such as telephone conversations, letters, etc.

What is an interactive model of communication?

As more dynamic models, interactive communication models refer to two-way communication with feedback.

However, feedback within interactive communication models is not simultaneous, but rather slow and indirect.

What are the main elements of interactive communication models?

The main elements of these models, illustrated in the interactive communication model diagram, include the following:

- Feedback , and

- Field of experience .

You probably noticed the new, previously not seen element — field of experience .

The field of experience represents a person’s culture, past experiences, and personal history.

All of these factors influence how the sender constructs a message, as well as how the receiver interprets it. Every one of us brings a unique field of experience into communication situations.

We have already mentioned the most noteworthy interactive models of communication.

Now it is time for us to consider them in greater detail.

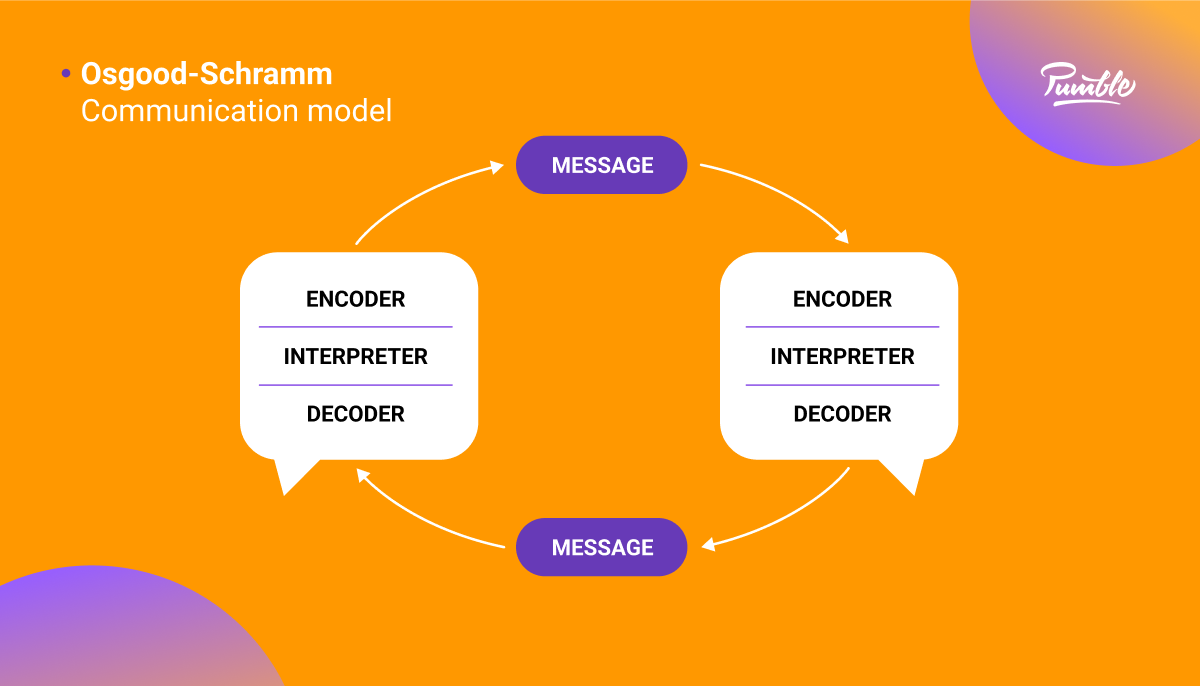

5. The Osgood-Schramm model of communication

In their book Communication Models for the Study of Mass Communications , Denis Mcquail and Sven Windahl say that the emergence of this model “meant a clear break with the traditional linear/one-way picture of communication.”

What is the Osgood-Schramm model of communication?

The Osgood-Schramm model is a circular model of communication, in which messages go in two directions between encoding and decoding.

As such, this model is useful for describing synchronous, interpersonal communication , but less suitable for cases with little or no feedback.

Interestingly, in the Osgood-Schramm communication model, there is no difference between a sender and a receiver . Both parties are equally encoding and decoding the messages. The interpreter is the person trying to understand the message at that moment.

Furthermore, the Osgood-Schramm communication model shows that information is of no use until it is put into words and conveyed to other people.

What are the main principles and steps in the communication process according to this model?

The Osgood-Schramm communication model proposes 4 main principles of communication:

- Communication is circular. — Individuals involved in the communication process are changing their roles as encoders and decoders.

- Communication is equal and reciprocal. — Both parties are equally engaged as encoders and decoders.

- The message requires interpretation. — The information needs to be properly interpreted to be understood.

- As shown in the Osgood-Schramm communication model diagram below, this model proposes 3 steps in the process of communication:

- Decoding , and

- Interpreting .

The Osgood-Schramm communication model example

Imagine you have not heard from your college friend for 15 years. Suddenly, they call you, and you start updating each other about what happened during the time you have not seen each other.

In this example, you and your friend are equally encoding and decoding messages, and your communication is synchronous. You are both interpreting each other’s messages.

In Information Theory and Mass Communication , Schramm even says:

“ It is misleading to think of the communication process as starting somewhere and ending somewhere. It is really endless. We are really switchboard centers handling and re-routing the great endless current of information .”

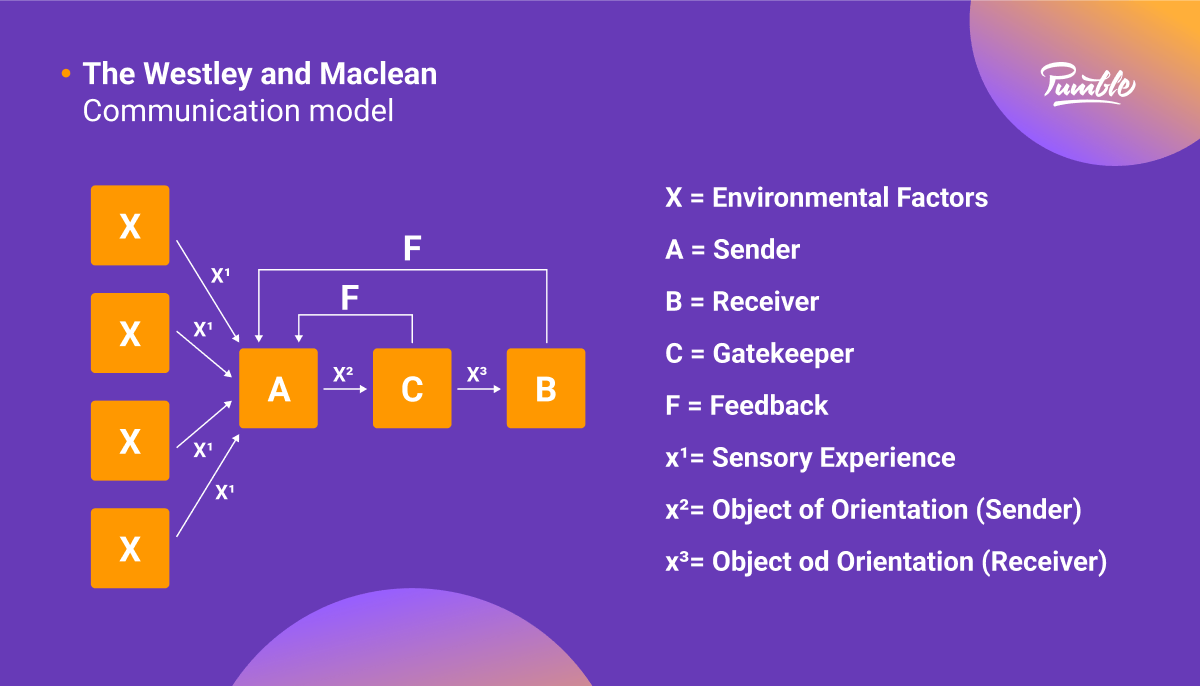

6. The Westley and Maclean model of communication

The next interactive communication model on our list is the Westley and Maclean model of communication.

This communication model is primarily used for explaining mass communication.

What is the Westley and Maclean communication model?

The Westley and Maclean communication model suggests that the communication process does not start with the source/sender, but rather with environmental factors .

This model also takes into account the object of the orientation (background, culture, and beliefs) of the sender and the receiver of messages.

The very process of communication, according to this communication model, starts with environmental factors that influence the speaker — the culture or society the speaker lives in, whether the speaker is in a public or private space, etc.

Aside from that, the role of feedback is also significant.

What are the main elements of the Westley and Maclean communication model?

This model consists of 9 crucial components:

- Environment (X) ,

- Sensory experience (X¹) ,

- Source/Sender (A) ,

- The object of the orientation of the source (X²) ,

- Receiver (B) ,

- The object of the orientation of the receiver (X³) ,

- Feedback (F) ,

- Gatekeepers (C) , and

- Opinion leaders .

The Westley and Maclean communication model diagram below shows how these components are organized in the communication process.

The Westley and Maclean communication model example

Imagine that on your way to the office, you witness a road accident.

This is the type of stimulus that would nudge you to call your friends and tell them about what you had seen, or call your boss to say you are going to be a bit late.

So, the communication process in this example does not start with you, but with the road accident you have witnessed.

Acknowledgment of the environmental factors in communication, therefore, allows us to pay attention to the social and cultural contexts that influence our acts of communication.

Now that we have seen what the elements of communication in this model are, let’s look at all of them in greater detail.

9 Key elements of communication in the Westley and Maclean communication model

As mentioned above, this model shows that the communication process does not start from the sender of the message, but rather from the environment.

So, we will start with this element.

Element #1: Environment (X)

According to the Westley and Maclean Model, the communication process starts when a stimulus from the environment motivates a person to create and send a message.

Element #2: Sensory experience (X¹)

When the sender of the message experiences something in their environment that nudges them to send the message, then that sensory experience becomes an element of communication.

In the example above, the sensory experience would be witnessing a road accident.

Element #3: Source/Sender (A)

Only now does the sender come into play.

In the above-mentioned example, you are the sender, as well as a participant in the interpersonal communication situation .

However, a sender can also be a newscaster sending a message to millions of viewers. In that case, we are talking about mass communication .

Element #4: The object of the orientation of the source (X²)

The next element of communication in this model is the object of the orientation of the source.

Namely, the object of the orientation of the source is the sender’s beliefs or experiences .

If we take the previously-mentioned road accident as an example, you (A) are concerned (X²) that you are going to be late for work because of the accident (X¹), and that is why you are calling your boss (B).

Element #5: Receiver (B)

The receiver is the person who receives the message from the sender.

In mass communication, a receiver is a person who watches TV, reads a newspaper, etc.

When speaking about interpersonal communication, a receiver is a person who listens to the message .

In the example of a road accident, mentioned above, the receivers of the message are your friends and your boss.

Element #6: The object of the orientation of the receiver (X³)

The object of orientation of the receiver is the receiver’s beliefs or experiences , which influence how the message is received.

For example, your friend (B) watching the news is worried about your safety (X³) after receiving the message.

Element #7: Feedback (F)

Feedback is crucial for this model because it makes this model circular, rather than linear.

As a matter of fact, feedback influences how messages are sent .

That means that a receiver and a gatekeeper are sending messages back to the sender.

After they have received the feedback, the sender modifies the message and sends it back.

Let’s go back to our example (about the road accident).

So, you have witnessed the accident and feel the urge to call your best friend.

You: “There was a terrible accident downtown!”

Your friend: “My goodness! Are you hurt?”

You: “No, no, I just witnessed it. I wasn’t involved! Don’t worry!”

In this example, after the feedback from your worried friend, you modify your message and send it back to them.

Element #8: Gatekeepers (C)

This element usually occurs in mass communication, rather than in interpersonal communication.

Gatekeepers are editors of the messages senders are trying to communicate to receivers.

For example, these are newspaper editors who edit the message before it reaches the readers.

Element #9: Opinion leaders

Again, this element of communication refers to mass communication situations.

Namely, opinion leaders have an immense influence as an environmental factor (X) on the sender of the message (A).

These are political leaders, celebrities, or social media influencers.

Now that we are familiar with interactive models, all we have left to analyze are the transactional communication models.

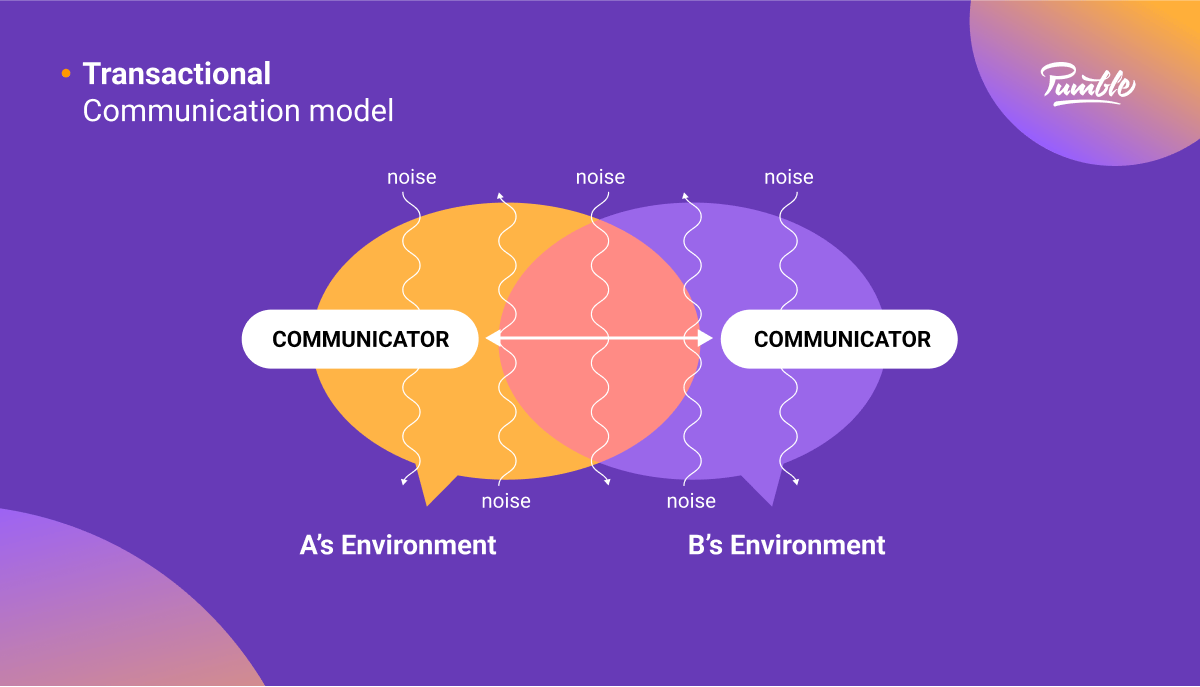

Transactional communication models

Transactional models are the most dynamic communication models, which first introduce a new term for senders and receivers — communicators.

What is a transactional communication model?

Transactional communication models view communication as a transaction , meaning that it is a cooperative process in which communicators co-create the process of communication, thereby influencing its outcome and effectiveness.

In other words, communicators create shared meaning in a dynamic process .

Aside from that, transactional models show that we do not just exchange information during our interactions, but create relationships, form cross-cultural bonds, and shape our opinions.

In other words, communication helps us establish our realities .

These models also introduced the roles of:

- Social,

- Relational, and

- Cultural contexts.

Moreover, these models acknowledge that there are barriers to effective communication — noise .

What are the main elements of transactional communication models?

If we take a look at the transactional communication model diagram below, we can identify the key components of this communication model:

- Decoding ,

- Communicators ,

- The message ,

- The channel , and

- Noise .

We have already mentioned the most prominent transactional models of communication, and now it is time to thoroughly analyze them.

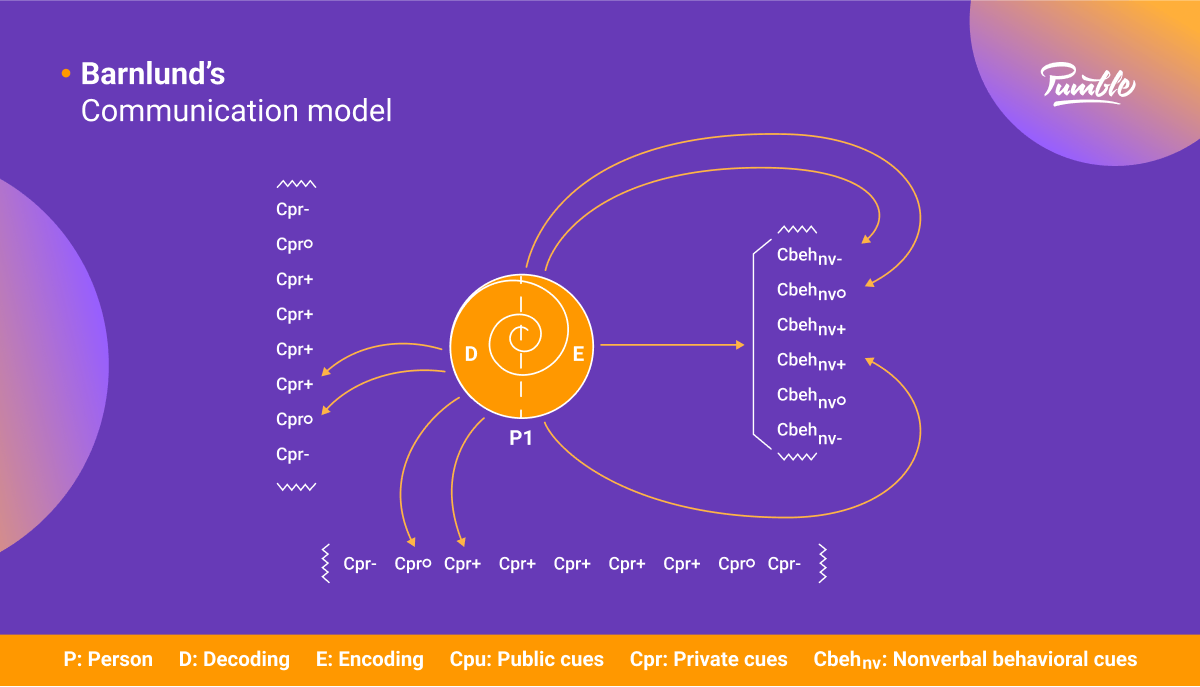

7. Barnlund’s transactional model of communication

Barnlund’s transactional communication model explores interpersonal, immediate-feedback communication.

What is Barnlund’s transactional communication model?

Barnlund’s model of communication recognizes that communication is a circular process and a multi-layered feedback system between the sender and the receiver, both of whom can affect the message being sent.

The sender and the receiver change their places and are equally important. Feedback from the sender is the reply for the receiver, and both communicators provide feedback.

At the same time, both sender and receiver are responsible for the communication’s effect and effectiveness.

What are the main elements of Barnlund’s communication model?

Barnlund’s transactional communication model diagram below illustrates the following main components of this communication model:

- The message (including the cues, environment, and noise), and

- The channel .

This model accentuates the role of cues in impacting our messages.

So, Barnlund differentiates between:

- Public cues (environmental cues),

- Private cues (person’s personal thoughts and background), and

- Behavioral cues (person’s behavior, that can be verbal and nonverbal).

All these cues, as well as the environment and noise, are part of the message. Each communicator’s reaction depends on their background, experiences, attitudes, and beliefs.

Barnlund’s transactional communication model example

Examples of Barnlund’s Model of communication include:

- Face-to-face interactions,

- Chat sessions ,

- Telephone conversations,

- Meetings , etc.

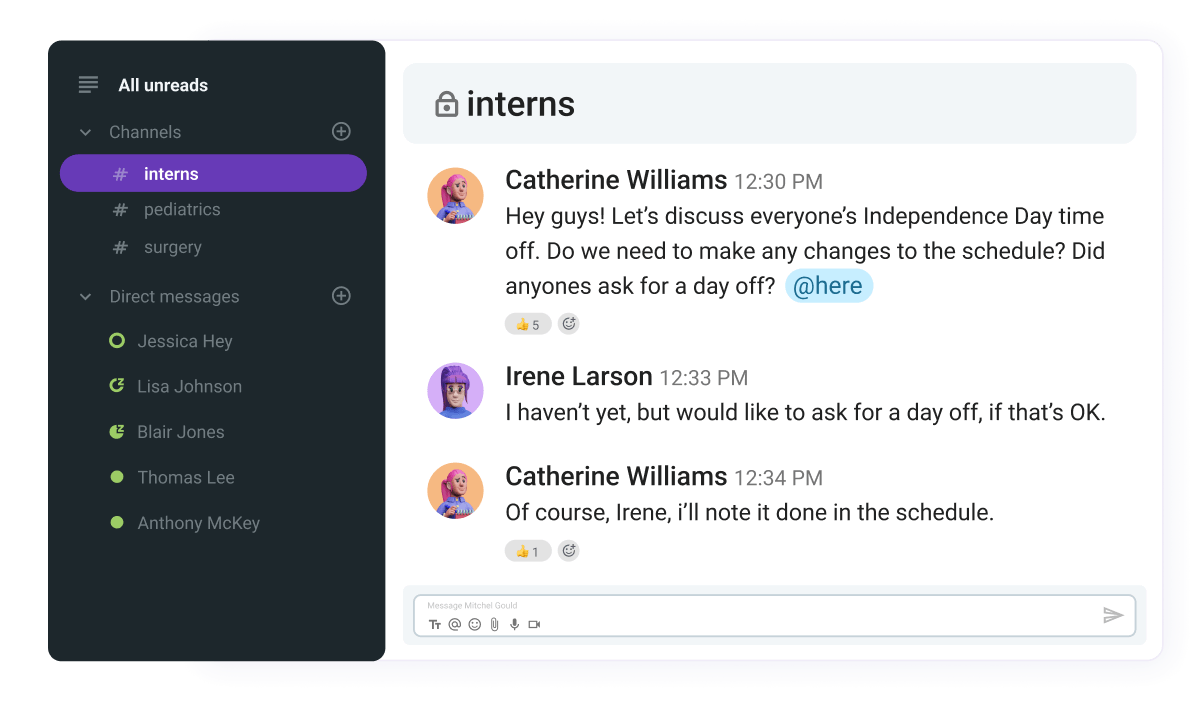

Let’s illustrate this model with an example from a business messaging app Pumble .

Why was there a misunderstanding in this conversation even though everything seemed fine at first glance?

This misunderstanding has arisen due to cultural cues.

Namely, Catherine had thought that Irene wanted a day off on July 4th.

However, Irene comes from Canada and celebrates Independence Day on July 1st.

On that day, she does not show up at work to Catherine’s bewilderment, because she has expected Irene to take a day off on July 4th, on US Independence Day.

So, due to cultural cues, there was a misunderstanding between them.

Still, this misunderstanding could have easily been avoided, had they cleared up the dates by providing each other with feedback.

8. Dance’s Helical model of communication

According to Dance’s Helical model of communication, with every cycle of communication, we expand our circle.

Therefore, each communication encounter is different from the previous one because communication never repeats itself.

What is Dance’s Helical communication model?

Dance’s Helical communication model views communication as a circular process that gets more and more complex as communication progresses.

That is why it is represented by a helical spiral in the Dance’s Helical communication model diagram below.

In their book Communication: Principles for a Lifetime , Steven A. Beebe, Susan J. Beebe, and Diana K. Ivy state:

“Interpersonal communication is irreversible. Like the spiral shown here, communication never loops back on itself. Once it begins, it expands infinitely as the communication partners contribute their thoughts and experiences to the exchange.” Steven A. Beebe, Susan J. Beebe, Diana K. Ivy

According to this communication model, in the communication process, the feedback we get from the other party involved influences our next statement and we become more knowledgeable with every new cycle.

Dance’s Helical communication model example

Dance himself explained his model with the example of a person learning throughout their life.

Namely, a person starts to communicate with their surroundings very early on, using rudimentary methods of communication.

For instance, as babies, we cry to get our mothers’ attention. Later on, we learn to speak in words, and then in full sentences.

During the whole process, we build on what we know to improve our communication.

Every communication act is, therefore, a chance for us to learn how to communicate more effectively in the future, and feedback helps us achieve more effective communication.

In a way, our whole life is one communicational journey toward the top of Dance’s helix.

Wrapping up: Communication models help us solve our workplace communication problems

Communication in real life might be too complex to be truly represented by communication models.

However, models of communication can still help us examine the steps in the process of communication, so we can better understand how we communicate both in the workplace and outside of it.

Let’s sum up the key takeaways from this guide.

In this guide, we have covered the most important models of communication, divided into 3 categories:

- Linear models — Mainly used in marketing, sales, and PR, in communication with customers, these models view communication as a one-way process.

- Interactive models — Used in internet-based and mediated communication, they refer to two-way communication with indirect feedback.

- Transactional models — The most complex models of communication, which best reflect the communication process.

Although none of these models represent our communication 100%, they can help us detect and solve potential problems and improve our communication skills.

References:

- Beebe, S. A., Beebe, S. J., & Ivy, D. K. (2022). Communication: Principles for a lifetime . Pearson Education Limited.

- Berlo, David K. (1960). The Process of Communication . Harcourt School.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (n.d.). Models of communication . Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/communication/Models-of-communication

- Fiske, J. (2011). Introduction to communication studies . Routledge.

- Hartley, J. (2020). Communication, cultural and Media Studies: The key concepts . Routledge.

- Iyer, N., Veenstra, A. S., & Sapienza, Z. (2015, January 1). Reading Lasswell’s model of communication backward: Three scholarly misconceptions . Mass Communication and Society. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www.academia.edu/13182400/Reading_Lasswells_Model_of_Communication_Backward_Three_Scholarly_Misconceptions

- Jones, R. G. (2018). Communication in the real world . Flat World Knowledge.

- Learning, L. (n.d.). Principles of public speaking . Principles of Public Speaking | Simple Book Production. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/publicspeakingprinciples/

- McQuail, D. (2012). McQuail’s mass communication theory . SAGE.

- McQuail, D., & Windahl, S. (2016). Communication models: For the study of Mass Communications . Routledge.

- MSG Management Study Guide . Communication Models – Aristotle, Berlos, Shannon and Weaver, Schramms. (n.d.). Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www.managementstudyguide.com/communication-models.htm

- Pierce, T., & Corey, A. M. (2009). The evolution of human communication: From theory to practice . EtrePress.

- Schramm, W. (1955). Information theory and mass … – journals.sagepub.com . SAGE Journals. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/107769905503200201

Explore further

Team Communication Fundamentals

Improving Team Communication

Improving Communication Effectiveness

Additional Materials

Free team chat app

Improve collaboration and cut down on emails by moving your team communication to Pumble.

Classic Models of Communication

- First Online: 02 December 2023

Cite this chapter

- Jessica Röhner 3 &

- Astrid Schütz 3

694 Accesses

This chapter will discuss influential conceptual approaches to human communication. It will begin with a general overview of psychological communication models before introducing a selection of classic models of communication.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alsaker, F. (2019). Mobbing [Bullying]. In M. A. Wirtz (Ed.), Dorsch – Lexikon der Psychologie (19th ed.). Hogrefe. https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/mobbing/

Google Scholar

Bauer, J. (2005). Die Neurobiologie der Empathie. Warum wir andere Menschen verstehen können [The neurobiology of empathy. Why we can understand other people]. Psychologie Heute, 32, 50–53.

Bensch, D., Maaß, U., Greiff, S., Horstmann, K. T., & Ziegler, M. (2019). The nature of faking: A homogeneous and predictable construct? Psychological Assessment, 31 (4), 532–544. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000619

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bond, C. F., & DePaulo, B. M. (2006). Accuracy of deception judgments. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10 (3), 214–234. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_2

Bühler, K. (1934). Sprachtheorie. Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache [Language Theory. The Representation Function of Language] . Fischer-Verlag.

Dehn-Hindenberg, A. (2007). Die Bedeutung von Kommunikation und Empathie im Therapieprozess: Patientenbedürfnisse in der Ergotherapie [The importance of communication and empathy in the therapeutic process. Patient needs in occupational therapy]. Ergotherapie und Rehabilitation, 46 (7) , 5–10.

DePaulo, B. M., Charlton, K., Cooper, H., Lindsay, J. J., & Muhlenbruck, L. (1997). The accuracy-confidence correlation in the detection of deception. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1 (4), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0104_5

DePaulo, B. M., Kashy, D. A., Kirkendol, S. E., Wyer, M. M., & Epstein, J. A. (1996). Lying in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (5), 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.979

Engen, H. G., & Singer, T. (2013). Empathy circuits. Current Opinion in Neurobiology , 23 (2) , 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2012.11.003

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. In P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (Eds.) Syntax and Semantics (Vol. 3, pp. 41–58). Academic Press.

Heringer, H. J. (2017). Interkulturelle Kommunikation [Intercultural Communication] (5th ed.). UTB.

Krauss, R. M., & Fussell, S. R. (1996). Social psychological models of interpersonal communication. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles (pp. 655–701). The Guilford Press.

Lamm, C., & Majdandžić, J. (2015). The role of shared neural activations, mirror neurons, and morality in empathy – A critical comment. Neuroscience Research, 90 , 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2014.10.008

Nietzsche, F. (1886). Also sprach Zarathustra [Thus Spake Zarathustra] . Reclam.

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory . Constable.

Rogers, C. (1961). On Becoming a Person. A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy . Constable.

Röhner, J., & Ewers, T. (2016). Trying to separate the wheat from the chaff: Construct- and faking-related variance on the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Behavior Research Methods , 48 , 243–258. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0568-1

Röhner, J., & Schütz, A. (2019a). Faking behavior. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences . Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_2341-1

Chapter Google Scholar

Röhner, J., & Schütz, A. (2019b). Fälschung eines erwünschten Eindrucks [Faking a desired impression]. In M. A. Wirtz (Ed.), Dorsch – Lexikon der Psychologie (19th ed., p. 583). Hogrefe.

Röhner, J., & Schütz, A. (2019c). Fälschung eines unerwünschten Eindrucks [Faking an undesired impression]. In M. A. Wirtz (Ed.), Dorsch – Lexikon der Psychologie (19th ed., p. 583). Hogrefe.

Röhner, J., & Schütz, A. (2020). Verfälschungsverhalten in Psychologischer Diagnostik. Report Psychologie, 45 , 16–23.

Röhner, J., & Schütz, A. (Eds.). (2021). Essenzen – Im Gespräch mit Paul Watzlawick [Essences – Conversing with Paul Watzlawick] . Hogrefe.

Röhner, J., & Schütz, A. (2023). Phänomene der Antwortverzerrung in der Diagnostik [Phenomena of Response Biases in Diagnostics] . Hogrefe.

Röhner, J., Thoss, P. J., & Schütz, A. (2022). Lying on the dissection table: Anatomizing faked responses. Behavior Research Methods, 54 , 2878–2904. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01770-8

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schulz von Thun, F. (1981). Miteinander reden 1: Störungen und Klärungen. Allgemeine Psychologie der Kommunikation [Talking to Each Other 1 – Disturbances and Clarifications. General Psychology of Communication] . Rowohlt.

Schulz von Thun, F. (2000). Miteinander reden. Menschliche Kommunikation [Talking to Each Other. Human Communication] . Huber.

Schütz, A. (1999). It was your fault! Self-serving biases in autobiographical accounts of conflicts in married couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16 (2), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407599162004

Article Google Scholar

Schütz, A. (2005). Je selbstsicherer, desto besser? Licht und Schatten positive Selbstbewertung [The More Confident, the Better? Light and Shadow of a Positive Self-Image] . Beltz.

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The Mathematical Theory of Communication . University of Illinois Press.

Temple, T., & Frings, C. (2020). Spiegelneurone [Mirror neurons]. In M. A. Wirtz (Ed.), Dorsch – Lexikon der Psychologie (19th ed.). Hogrefe. https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/spiegelneurone/

Vrij, A., & Granhag, P. A. (2014). Eliciting information and detecting lies in intelligence interviewing: An overview of recent research. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28 (6), 936–944. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3071

Watzlawick, P. (1969). Menschliche Kommunikation [Human Communication] . Huber.

Watzlawick, P. (1983). Anleitung zum Unglücklichsein [Guide to Unhappiness] . Piper.

Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J. H., & Jackson, D. D. (2017). Menschliche Kommunikation. Formen, Störungen, Paradoxien [Human Communication. Forms, Disorders, Paradoxes] (13th ed.). Hogrefe.

Weiss, B., & Feldman, R. S. (2006). Looking good and lying to do it: Deception as an impression management strategy in job interviews. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36 (4), 1070–1086. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00055.x

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany

Jessica Röhner & Astrid Schütz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jessica Röhner .

Answers to the Comprehension Questions

1. Encoder/decoder models, intentionalist models, perspective-taking models, and dialogic models.

2. Source of information (sender), transmitter (encoder), signal, channel, addressee (recipient), receiver (decoder), and interferences.

3. Factual level, self-revelation, relationship, and appeal.

4. Maxim of relation.

5. Putting ourselves in another person’s shoes and telling them what we understand.

6. All behavior communicates something. Even when we are silent, we are communicating.

7. “White lies” are told without bad intentions and are often little embellishments. “Black lies” are malicious or selfish and are told to harm others. Both types of lies violate the maxim of quality.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Röhner, J., Schütz, A. (2023). Classic Models of Communication. In: Psychology of Communication. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60170-6_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60170-6_2

Published : 02 December 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-47090-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-60170-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Definitions and Concepts of Communication

Introduction, general overviews.

- Reference Works

- Anthologies

- Online Bibliographies

- History of the Idea

- Culturally Based Concepts

- Conceptual Models and Metaphors

- Multiplicity of Definitions

- Intentionality, Behavior, and Systems

- Metacommunication and Paradox

- Representation, Experience, and Mutual Understanding

- Incommunicability and the Limits of Communication

- Communication as Constitutive

- Materiality and Discursivity

- Machine and Human Communication

- Communicative Action, Strategic Action, and Dialogue

- Communication as Ideology

- Cultural Bias and De-Westernization

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Codes and Cultural Discourse Analysis

- Communication History

- Critical and Cultural Studies

- Ethnography of Communication

- Global Englishes

- Intercultural Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International Communications

- Interpretation/Reception

- Media Sociology

- Philosophy of Communication

- Religion and the Media

- Religious Rhetoric

- Sense-Making/Sensemaking

- The Interface between Organizational Change and Organizational Change Communication

- Wilbur Schramm

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Media Streaming

- Web3 and Communication

- Find more forthcoming titles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Definitions and Concepts of Communication by Robert T. Craig LAST REVIEWED: 15 April 2024 LAST MODIFIED: 21 June 2024 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756841-0172

What is communication? The question is deceptively simple, not because there is no straightforward answer but because there are so many answers, many of which may seem perfectly straightforward in themselves. Communication is human interaction . . . the transfer of information . . . effect or influence . . . mutual understanding . . . community . . . culture . . . and so on. Any effort to reconcile these straightforward definitions quickly runs into contradictions and puzzles. Human interaction involves the transfer of information, but machines also exchange information, and so do animals and chemical molecules. Is human communication essentially different in some way? Effect or influence is not the same as mutual understanding and is sometimes quite the opposite. Is mutual understanding ever really possible? Is communication an intentional act or a process that goes on regardless of our intentions? If communication is culture, is it necessarily also community? Doesn’t the concept of communication vary, depending on how it is understood and practiced in each culture? Is it all relative, then, or are there good reasons to be critical of some cultural concepts? Obviously, communication can be defined in many different ways, and at least some of those differences seem potentially consequential. Whether we think of communication as essentially information transfer, or mutual understanding, or culture can make a difference, not only for how we understand the process intellectually but also for how we communicate in practice. Of course, we need not all agree on a single definition or choose a single definition for ourselves, but we can learn a lot by contemplating and debating the theoretical and practical implications of different concepts and theories of communication. This is what communication theorists do, and the academic subject of communication theory is a rich and varied resource for learning how to think about communication. The field of communication theory encompasses several distinct intellectual traditions, some thousands of years old, others very new. Some theories lend themselves to scientific empirical studies of communication, others to philosophical reflection or cultural criticism. This article is intended to represent the diversity of communication theory, hopefully in ways that are useful and inviting of further study rather than merely confusing. Included are introductory overview essays, textbooks, and other general sources such as encyclopedias, anthologies, and journals. Other sections cover historical studies on the idea of communication, ethnographic studies on culturally based concepts of communication, and theoretical models of the communication process. The section titled Conceptual Issues is divided into eleven subsections, each focusing on a key conceptual issue or controversy in communication theory.

For readers wanting to dip a toe in communication theory before diving in, the articles in this section provide overviews of the concept of communication while introducing important issues and conceptual approaches. Eadie and Goret 2013 surveys key concepts of communication that have influenced the academic field of communication studies. Cobley 2008 sketches the origins and historical development of the concept of communication. Steinfatt 2009 discusses the problem of defining communication and some characteristics of communication that affect the usefulness of definitions. Craig 1999 presents a conceptual model of communication theory as a field that integrates seven distinct intellectual traditions.

Cobley, Paul. 2008. Communication: Definitions and concepts. In International encyclopedia of communication . Edited by Wolfgang Donsbach. Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Sketches the ancient origins of the concept of communication, the distinction between communication as process and product, the social uses of communication, and 20th-century concepts that contributed to communication theory. Also notes the importance of understanding miscommunication.

Craig, Robert T. 1999. Communication theory as a field. Communication Theory 9.2:119–161.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.1999.tb00355.x

Conceptualizes communication theory as a field of “metadiscursive practice” in which diverse theoretical concepts of communication are engaged with each other and with ordinary (nontheoretical) concepts in ongoing debates about practical communication problems. Identifies seven interdisciplinary “traditions” of communication theory, each grounded in a distinct, practically oriented definition of communication.

Eadie, William F., and Robin Goret. 2013. Theories and models of communication: Foundations and heritage. In Theories and models of communication . Edited by Paul Cobley and Peter J. Schulz, 17–36. Handbooks of Communication Science, HOCS 1. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

With a focus on concepts of communication within the academic field of communication studies, this chapter organizes conceptions of communication under five broad categories: shaper of public opinion; language use; information transmission; developer of relationships; and definer, interpreter, and critic of culture.

Steinfatt, Thomas M. 2009. Definitions of communication. In Encyclopedia of communication theory . Edited by Stephen W. Littlejohn and Karen A. Foss. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Argues that the problem of defining communication is not to discover the correct meaning of the term but is rather to construct a definition that is useful for studying communication. Distinguishes several characteristics of communication that affect the usefulness of definitions. A critique of this piece is that it presupposes a transmission (speaker to listener) model of communication and fails to address alternative models that highlight constitutive, systemic, and other characteristics of communication (see under Conceptual Issues ).

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Communication »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Accounting Communication

- Acculturation Processes and Communication

- Action Assembly Theory

- Action-Implicative Discourse Analysis

- Activist Media

- Adherence and Communication

- Adolescence and the Media

- Advertisements, Televised Political

- Advertising

- Advertising, Children and

- Advertising, International

- Advocacy Journalism

- Agenda Setting

- Annenberg, Walter H.

- Apologies and Accounts

- Applied Communication Research Methods

- Argumentation

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Advertising

- Attitude-Behavior Consistency

- Audience Fragmentation

- Audience Studies

- Authoritarian Societies, Journalism in

- Bakhtin, Mikhail

- Bandwagon Effect

- Baudrillard, Jean

- Blockchain and Communication

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Brand Equity

- British and Irish Magazine, History of the

- Broadcasting, Public Service

- Capture, Media

- Castells, Manuel

- Celebrity and Public Persona

- Civil Rights Movement and the Media, The

- Co-Cultural Theory and Communication

- Cognitive Dissonance

- Collective Memory, Communication and

- Comedic News

- Communication Apprehension

- Communication Campaigns

- Communication, Definitions and Concepts of

- Communication Law

- Communication Management

- Communication Networks

- Communication, Philosophy of

- Community Attachment

- Community Journalism

- Community Structure Approach

- Computational Journalism

- Computer-Mediated Communication

- Content Analysis

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Communication

- Crisis Communication

- Critical Race Theory and Communication

- Cross-tools and Cross-media Effects

- Cultivation

- Cultural and Creative Industries

- Cultural Imperialism Theories

- Cultural Mapping

- Cultural Persuadables

- Cultural Pluralism and Communication

- Cyberpolitics

- Death, Dying, and Communication

- Debates, Televised

- Deliberation

- Developmental Communication

- Diffusion of Innovations

- Digital Divide

- Digital Gender Diversity

- Digital Intimacies

- Digital Literacy

- Diplomacy, Public

- Distributed Work, Comunication and

- Documentary and Communication

- E-democracy/E-participation

- E-Government

- Elaboration Likelihood Model

- Electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM)

- Embedded Coverage

- Entertainment

- Entertainment-Education

- Environmental Communication

- Ethnic Media

- Experiments

- Families, Multicultural

- Family Communication

- Federal Communications Commission

- Feminist and Queer Game Studies

- Feminist Data Studies

- Feminist Journalism

- Feminist Theory

- Focus Groups

- Food Studies and Communication

- Freedom of the Press

- Friendships, Intercultural

- Gatekeeping

- Gender and the Media

- Global Media, History of

- Global Media Organizations

- Glocalization

- Goffman, Erving

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Habituation and Communication

- Health Communication

- Hermeneutic Communication Studies

- Homelessness and Communication

- Hook-Up and Dating Apps

- Hostile Media Effect

- Identification with Media Characters

- Identity, Cultural

- Image Repair Theory

- Implicit Measurement

- Impression Management

- Infographics

- Information and Communication Technology for Development

- Information Management

- Information Overload

- Information Processing

- Infotainment

- Innis, Harold

- Instructional Communication

- Integrated Marketing Communications

- Interactivity

- Intercultural Capital

- Intercultural Communication, Tourism and

- Intercultural Communication, Worldview in

- Intercultural Competence

- Intercultural Conflict Mediation

- Intercultural Dialogue

- Intercultural New Media

- Intergenerational Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Interpersonal LGBTQ Communication

- Interpretive Communities

- Journalism, Accuracy in

- Journalism, Alternative

- Journalism and Trauma

- Journalism, Citizen

- Journalism, Citizen, History of

- Journalism Ethics

- Journalism, Interpretive

- Journalism, Peace

- Journalism, Tabloid

- Journalists, Violence against

- Knowledge Gap

- Lazarsfeld, Paul

- Leadership and Communication

- LGBTQ+ Family Communication

- Mass Communication

- McLuhan, Marshall

- Media Activism

- Media Aesthetics

- Media and Time

- Media Convergence

- Media Credibility

- Media Dependency

- Media Ecology

- Media Economics

- Media Economics, Theories of

- Media, Educational

- Media Effects

- Media Ethics

- Media Events

- Media Exposure Measurement

- Media, Gays and Lesbians in the

- Media Literacy

- Media Logic

- Media Management

- Media Policy and Governance

- Media Regulation

- Media, Social

- Media Systems Theory

- Merton, Robert K.

- Message Characteristics and Persuasion

- Mobile Communication Studies

- Multimodal Discourse Analysis, Approaches to

- Multinational Organizations, Communication and Culture in

- Murdoch, Rupert

- Narrative Engagement

- Narrative Persuasion

- Net Neutrality

- News Framing

- News Media Coverage of Women

- NGOs, Communication and

- Online Campaigning

- Open Access

- Organizational Change and Organizational Change Communicat...

- Organizational Communication

- Organizational Communication, Aging and

- Parasocial Theory in Communication

- Participation, Civic/Political

- Participatory Action Research

- Patient-Provider Communication

- Peacebuilding and Communication

- Perceived Realism

- Personalized Communication

- Persuasion and Social Influence

- Persuasion, Resisting

- Photojournalism

- Political Advertising

- Political Communication, Normative Analysis of

- Political Economy

- Political Knowledge

- Political Marketing

- Political Scandals

- Political Socialization

- Polls, Opinion

- Product Placement

- Public Interest Communication

- Public Opinion

- Public Relations

- Public Sphere

- Queer Intercultural Communication

- Queer Migration and Digital Media

- Race and Communication

- Racism and Communication

- Radio Studies

- Reality Television

- Reasoned Action Frameworks

- Reporting, Investigative

- Rhetoric and Communication

- Rhetoric and Intercultural Communication

- Rhetoric and Social Movements

- Rhetoric, Religious

- Rhetoric, Visual

- Risk Communication

- Rumor and Communication

- Schramm, Wilbur

- Science Communication

- Scripps, E. W.

- Selective Exposure

- Sesame Street

- Sex in the Media

- Small-Group Communication

- Social Capital

- Social Change

- Social Cognition

- Social Construction

- Social Identity Theory and Communication

- Social Interaction

- Social Movements

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Protest

- Sports Communication

- Stereotypes

- Strategic Communication

- Superdiversity

- Surveillance and Communication

- Symbolic Interactionism in Communication

- Synchrony in Intercultural Communication

- Tabloidization

- Telecommunications History/Policy

- Television, Cable

- Textual Analysis and Communication

- Third Culture Kids

- Third-Person Effect

- Time Warner

- Transgender Media Studies

- Transmedia Storytelling

- Two-Step Flow

- United Nations and Communication

- Urban Communication

- Uses and Gratifications

- Video Deficit

- Video Games and Communication

- Violence in the Media

- Virtual Reality and Communication

- Visual Communication

- Web Archiving

- Whistleblowing

- Whiteness Theory in Intercultural Communication

- Youth and Media

- Zines and Communication

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

IMAGES

VIDEO