An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Neuroscience of Happiness and Pleasure

Morten l kringelbach, kent c berridge.

- Copyright and License information

The evolutionary imperatives of survival and procreation, and their associated rewards, are driving life as most animals know it. Perhaps uniquely, humans are able to consciously experience these pleasures and even contemplate the elusive prospect of happiness. The advanced human ability to consciously predict and anticipate the outcome of choices and actions confers on our species an evolutionary advantage, but this is a double-edged sword, as John Steinbeck pointed out as he wrote of “the tragic miracle of consciousness” and how our “species is not set, has not jelled, but is still in a state of becoming” ( Steinbeck and Ricketts 1941 ). While consciousness allows us to experience pleasures, desires, and perhaps even happiness, this is always accompanied by the certainty of the end.

Nevertheless, while life may ultimately meet a tragic end, one could argue that if this is as good as it gets, we might as well enjoy the ride and in particular to maximize happiness. Yet, it is also true that for many happiness is a rare companion due to the competing influences of anxiety and depression.

In order to help understand happiness and alleviate the suffering, neuroscientists and psychologists have started to investigate the brain states associated with happiness components and to consider the relation to well-being. While happiness is in principle difficult to define and study, psychologists have made substantial progress in mapping its empirical features, and neuroscientists have made comparable progress in investigating the functional neuroanatomy of pleasure, which contributes importantly to happiness and is central to our sense of well-being.

In this article we will try to map out some of the intricate links between pleasure and happiness. Our main contention is that a better understanding of the pleasures of the brain may offer a more general insight into happiness, into how brains work to produce it in daily life for the fortunate, how brains fail in the less fortunate, and hopefully into better ways to enhance the quality of life.

A SCIENCE OF HAPPINESS?

As shown by the other contributions to this volume, there are many possible definitions and approaches to investigating happiness. Many would agree that happiness has remained difficult to define and challenging to measure—partly due to its subjective nature. Is it possible to get a scientific handle on such a slippery concept? There are several aids to start us off.

Since Aristotle, happiness has been usefully thought of as consisting of at least two aspects: hedonia (pleasure) and eudaimonia (a life well lived). In contemporary psychology these aspects are usually referred to as pleasure and meaning, and positive psychologists have recently proposed to add a third distinct component of engagement related to feelings of commitment and participation in life ( Seligman et al. 2005 ).

Using these definitions, scientists have made substantial progress in defining and measuring happiness in the form of self-reports of subjective well-being, in identifying its distribution across people in the real world, and in identifying how well-being is influenced by various life factors that range from income to other people ( Kahneman 1999 ). This research shows that while there is clearly a sharp conceptual distinction between pleasure versus engagement-meaning components, hedonic and eudaimonic aspects empirically cohere together in happy people.

For example, in happiness surveys, over 80 percent of people rate their overall eudaimonic life satisfaction as “pretty to very happy,” and comparably, 80 percent also rate their current hedonic mood as positive (for example, positive 6–7 on a 10 point valence scale, where 5 is hedonically neutral) ( Kesebir and Diener 2008 ). A lucky few may even live consistently around a hedonic point of 8—although excessively higher hedonic scores may actually impede attainment of life success, as measured by wealth, education, or political participation ( Oishi et al. 2007 ).

While these surveys provide interesting indicators of mental well-being, they offer little evidence of the underlying neurobiology of happiness. That is the quest we set ourselves here. But to progress in this direction, it is first necessary to make a start using whatever evidence is both relevant to the topic of well-being and happiness, and in which neuroscience has relative strengths. Pleasure and its basis offers a window of opportunity.

In the following we will therefore focus on the substantial progress in understanding the psychology and neurobiology of sensory pleasure that has been made over the last decade ( Berridge and Kringelbach 2008 ; Kringelbach and Berridge 2010 ). These advances make the hedonic side of happiness most tractable to a scientific approach to the neural underpinnings of happiness. Supporting a hedonic approach, it has been suggested that the best measure of subjective well-being may be simply to ask people how they hedonically feel right now—again and again—so as to track their hedonic accumulation across daily life ( Kahneman 1999 ). Such repeated self-reports of hedonic states could also be used to identify more stable neurobiological hedonic brain traits that dispose particular individuals toward happiness. Further, a hedonic approach might even offer a toehold into identifying eudaimonic brain signatures of happiness, due to the empirical convergence between the two categories, even if pleasant mood is only half the happiness story ( Kringelbach and Berridge 2009 ).

It is important to note that our focus on the hedonia component of happiness should not be confused with hedonism, which is the pursuit of pleasure for pleasure’s own sake, and more akin to the addiction features we describe below. Also, to focus on hedonics does not deny that some ascetics may have found bliss through painful self-sacrifice, but simply reflects that positive hedonic tone is indispensable to most people seeking happiness.

A SCIENCE OF PLEASURE

The link between pleasure and happiness has a long history in psychology. For example, that link was stressed in the writings of Sigmund Freud when he posited that people “strive after happiness; they want to become happy and to remain so. This endeavor has two sides, a positive and a negative aim. It aims, on the one hand, at an absence of pain and displeasure, and, on the other, at the experiencing of strong feelings of pleasure” ( Freud and Riviere 1930 : 76). Emphasizing a positive balance of affect to be happy implies that studies of hedonic brain circuits can advance the neuroscience of both pleasure and happiness.

A related but slightly different view is that happiness depends most chiefly on eliminating negative “pain and displeasure” to free an individual to pursue engagement and meaning. Positive pleasure by this view is somewhat superfluous. This view may characterize the twentieth-century medical and clinical emphasis on alleviating negative psychopathology and strongly distressing emotions. It fits also with William James’s quip nearly a century ago that “happiness, I have lately discovered, is no positive feeling, but a negative condition of freedom from a number of restrictive sensations of which our organism usually seems the seat. When they are wiped out, the clearness and cleanness of the contrast is happiness. This is why anaesthetics make us so happy. But don’t you take to drink on that account” ( James 1920 : 158).

Focusing on eliminating negative distress seems to leave positive pleasure outside the boundary of happiness, perhaps as an extra bonus or even an irrelevancy for ordinary pursuit. In practice, many mixtures of positive affect and negative affect may occur in individuals and cultures may vary in the importance of positive versus negative affect for happiness. For example, positive emotions are linked most strongly to ratings of life satisfaction overall in nations that stress self-expression, but alleviation of negative emotions may become relatively more important in nations that value individualism ( Kuppens et al. 2008 ).

By either hedonic view, psychology seems to be moving away from the stoic notion that affect states such as pleasure are simply irrelevant to happiness. The growing evidence for the importance of affect in psychology and neuroscience shows that a scientific account will have to involve hedonic pleasures and/or displeasures. To move toward a neuroscience of happiness, a neurobiological understanding is required of how positive and negative affect are balanced in the brain.

Thus, pleasure is an important component of happiness, according to most modern viewpoints. Given the potential contributions of hedonics to happiness, we now survey developments in understanding the brain mechanisms of pleasure. The scientific study of pleasure and affect was foreshadowed by the pioneering ideas of Charles Darwin, who examined the evolution of emotions and affective expressions, and suggested that these are adaptive responses to environmental situations. In that vein, pleasure “liking” and displeasure reactions are prominent affective reactions in the behavior and brains of all mammals ( Steiner et al. 2001 ) and likely had important evolutionary functions ( Kringelbach 2009 ). Neural mechanisms for generating affective reactions are present and similar in most mammalian brains, and thus appear to have been selected for and conserved across species ( Kringelbach 2010 ). Indeed, both positive affect and negative affect are recognized today as having adaptive functions ( Nesse 2004 ), and positive affect in particular has consequences in daily life for planning and building cognitive and emotional resources ( Fredrickson et al. 2008 ).

Such functional perspectives are consistent with a thesis that is crucial to our aim of identifying the neurobiological bases of happiness: that affective reactions such as pleasure have objective features beyond their subjective ones. This idea is important, since progress in affective neuroscience has been made recently by identifying objective aspects of pleasure reactions and triangulating toward underlying brain substrates. This scientific strategy divides the concept of affect into two parts: the affective state , which has objective aspects in behavioral, physiological, and neural reactions; and conscious affective feelings , seen as the subjective experience of emotion ( Kringelbach 2004 ). Note that such a definition allows conscious feelings to play a central role in hedonic experiences, but holds that the affective essence of a pleasure reaction is more than a conscious feeling. That objective “something more” is especially tractable to neuroscience investigations that involve brain manipulations and can be studied regardless of the availability or accuracy of corresponding subjective reports.

The available evidence suggests that brain mechanisms involved in fundamental pleasures (food and sexual pleasures) overlap with those for higher-order pleasures (for example, monetary, artistic, musical, altruistic, and transcendent pleasures) ( Kringelbach 2010 ).

From sensory pleasures and drugs of abuse to monetary, aesthetic and musical delights, all pleasures seem to involve the same hedonic brain systems, even when linked to anticipation and memory. Pleasures important to happiness, such as socializing with friends, and related traits of positive hedonic mood are thus all likely to draw upon the same neurobiological roots that evolved for sensory pleasures. The neural overlap may offer a way to generalize from fundamental pleasures that are best understood and so infer larger hedonic brain principles likely to contribute to happiness.

We note the rewarding properties for all pleasures are likely to be generated by hedonic brain circuits that are distinct from the mediation of other features of the same events (for example, sensory, cognitive) ( Kringelbach 2005 ). Thus, pleasure is never merely a sensation or a thought, but is instead an additional hedonic gloss generated by the brain via dedicated systems ( Frijda 2010 ).

THE NEUROANATOMY OF PLEASURE

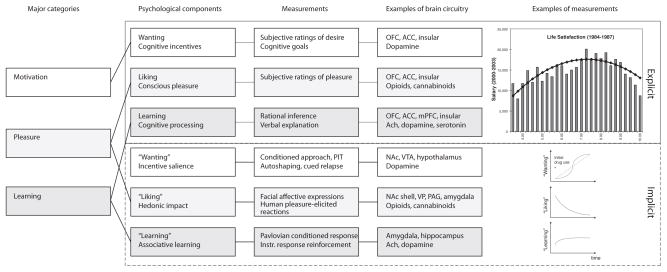

How does positive affect arise? Affective neuroscience research on sensory pleasure has revealed many networks of brain regions and neurotransmitters activated by pleasant events and states (see figures 1 and 2 ). Identification of hedonic substrates has been advanced by recognizing that pleasure or “liking” is but one component in the larger composite psychological process of reward, which also involves “wanting” and “learning” components ( Smith et al. 2010 ). Each component also has conscious and nonconscious elements that can be studied in humans—and at least the latter can also be probed in other animals.

Figure 1. Measuring Reward and Hedonia.

Reward and pleasure are multifaceted psychological concepts. Major processes within reward (first column) consist of motivation or wanting (white), learning (light gray), and—most relevant to happiness—pleasure liking or affect (gray). Each of these contains explicit (top three rows) and implicit (bottom three rows) psychological components (second column) that constantly interact and require careful scientific experimentation to tease apart. Explicit processes are consciously experienced (for example, explicit pleasure and happiness, desire, or expectation), whereas implicit psychological processes are potentially unconscious in the sense that they can operate at a level not always directly accessible to conscious experience (implicit incentive salience, habits and “liking” reactions), and must be further translated by other mechanisms into subjective feelings. Measurements or behavioral procedures that are especially sensitive markers of the each of the processes are listed (third column). Examples of some of the brain regions and neurotransmitters are listed (fourth column), as well as specific examples of measurements (fifth column), such as an example of how highest subjective life satisfaction does not lead to the highest salaries (top) ( Haisken-De New and Frick 2005 ). Another example shows the incentive-sensitization model of addiction and how “wanting” to take drugs may grow over time independently of “liking” and “learning” drug pleasure as an individual becomes an addict (bottom) ( Robinson and Berridge 1993 ).

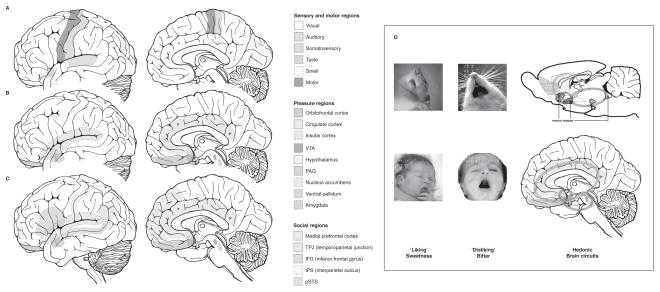

Figure 2. Hedonic Brain Circuitry.

The schematic figure shows the approximate sensorimotor, pleasure, and social brain regions in the adult brain. (a) Processing linked to the identification of and interaction with stimuli is carried out in the sensorimotor regions of the brain, (b) which are separate from the valence processing in the pleasure regions of the brain. (c) In addition to this pleasure processing, there is further higher-order processing of social situations (such as theory of mind) in widespread cortical regions. (d) The hedonic mammalian brain circuitry can be revealed using behavioral and subjective measures of pleasures in rodents and humans ( Berridge and Kringelbach 2008 ).

HEDONIC HOTSPOTS

Despite having extensive distribution of reward-related circuitry, the brain appears rather frugal in “liking” mechanisms that cause pleasure reactions. Some hedonic mechanisms are found deep in the brain (nucleus accumbens, ventral pallidum, brainstem) and other candidates are in the cortex (orbitofrontal, cingulate, medial prefrontal and insular cortices). Pleasure-activated brain networks are widespread and provide evidence for highly distributed brain coding of hedonic states, but compelling evidence for pleasure causation (detected as increases in “liking” reactions consequent to brain manipulation) has so far been found for only a few hedonic hotspots in the subcortical structures. Each hotspot is merely a cubic millimeter or so in volume in the rodent brain (and should be a cubic centimeter or so in humans, if proportional to whole brain volume). Hotspots are capable of generating enhancements of “liking” reactions to a sensory pleasure such as sweetness, when stimulated with opioid, endocannabinoid, or other neurochemical modulators ( Smith et al. 2010 ).

Hotspots exist in the nucleus accumbens shell and ventral pallidum, and possibly other forebrain and limbic cortical regions, and also in deep brainstem regions, including the parabrachial nucleus in the pons (see figure 2d ). The pleasure-generating capacity of these hotspots has been revealed in part by studies in which micro-injections of drugs stimulated neurochemical receptors on neurons within a hotspot, and caused a doubling or tripling of the number of hedonic “liking” reactions normally elicited by a pleasant sucrose taste. Analogous to scattered islands that form a single archipelago, hedonic hotspots are anatomically distributed but interact to form a functional integrated circuit. The circuit obeys control rules that are largely hierarchical and organized into brain levels. Top levels function together as a cooperative heterarchy, so that, for example, multiple unanimous “votes” in favor from simultaneously participating hotspots in the nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum are required for opioid stimulation in either forebrain site to enhance “liking” above normal.

In addition, as mentioned above, pleasure is translated into motivational processes in part by activating a second component of reward termed “wanting” or incentive salience, which makes stimuli attractive when attributed to them by mesolimbic brain systems ( Berridge and Robinson 2003 ). Incentive salience depends in particular on mesolimbic dopamine neurotransmission (though other neurotransmitters and structures also are involved).

Importantly, incentive salience is not hedonic impact or pleasure “liking” ( Berridge 2007 ). This is why an individual can “want” a reward without necessarily “liking” the same reward. Irrational “wanting” without liking can occur especially in addiction via incentive-sensitization of the mesolimbic dopamine system and connected structures. At extreme, the addict may come to “want” what is neither “liked” nor expected to be liked, a dissociation possible because “wanting” mechanisms are largely subcortical and separable from cortically mediated declarative expectation and conscious planning. This is a reason why addicts may compulsively “want” to take drugs even if, at a more cognitive and conscious level, they do not want to do so. That is surely a recipe for great unhappiness (see figure 2 , bottom right).

CORTICAL PLEASURE

In the cortex, hedonic evaluation of pleasure valence is anatomically distinguishable from precursor operations such as sensory computations, suggesting existence of a hedonic cortex proper ( figure 2 ). Hedonic cortex involves regions such as the orbitofrontal, insula, medial prefrontal and cingulate cortices, which a wealth of human neuroimaging studies have shown to code for hedonic evaluations (including anticipation, appraisal, experience, and memory of pleasurable stimuli) and have close anatomical links to subcortical hedonic hotspots. It is important, however, to again make a distinction between brain activity coding and causing pleasure. Neural coding is inferred in practice by measuring brain activity correlated to a pleasant stimulus, using human neuroimaging techniques, or electrophysiological or neurochemical activation measures in animals ( Aldridge and Berridge 2010 ). Causation is generally inferred on the basis of a change in pleasure as a consequence of a brain manipulation, such as a lesion or stimulation. Coding and causation often go together for the same substrate, but they may diverge so that coding occurs alone.

Pleasure encoding may reach an apex of cortical localization in a subregion that is midanterior and roughly midlateral within the orbitofrontal cortex of the prefrontal lobe, where neuroimaging activity correlates strongly to subjective pleasantness ratings of food varieties—and to other pleasures such as sexual orgasms, drugs, chocolate, and music. Most important, activity in this special midanterior zone of orbitofrontal cortex tracks changes in subjective pleasure, such as a decline in palatability when the reward value of one food was reduced by eating it to satiety (while remaining high to another food). The midanterior subregion of orbitofrontal cortex is thus a prime candidate for the coding of subjective experience of pleasure ( Kringelbach 2005 ).

Another potential coding site for positive hedonics in orbitofrontal cortex is along its medial edge that has activity related to the positive and negative valence of affective events ( Kringelbach and Rolls 2004 ), contrasted to lateral portions that have been suggested to code unpleasant events (although lateral activity may reflect a signal to escape the situation, rather than displeasure per se) ( O’Doherty et al. 2001 ). This medial–lateral hedonic gradient interacts with an abstraction–concreteness gradient in the posterior-anterior dimension, so that more complex or abstract reinforcers (such as monetary gain and loss) are represented more anteriorly in the orbitofrontal cortex than less complex sensory rewards (such as taste). The medial region that codes pleasant sensations does not, however, appear to change its activity with reinforcer devaluation, and so may not reflect the full dynamics of pleasure.

Still other cortical regions have been implicated by some studies in coding for pleasant stimuli, including parts of the mid-insular cortex that is buried deep within the lateral surface of the brain as well as parts of the anterior cingulate cortices on the medial surface of the cortex. As yet, however, pleasure coding is not as clear for those regions as for the orbitofrontal cortex, and it remains uncertain whether insular or anterior cingulate cortices specifically code pleasure or only emotion more generally. A related suggestion has emerged that the frontal left hemisphere plays a special lateralized role in positive affect more than the right hemisphere ( Davidson and Irwin 1999 ), though how to reconcile left-positive findings with many other findings of bilateral activations of orbitofrontal and related cortical regions during hedonic processing remains an ongoing puzzle ( Kringelbach 2005 ).

It remains still unknown, however, if even the midanterior pleasure-coding site of orbitofrontal cortex or medial orbitofrontal cortex or any other cortical region actually causes a positive pleasure state. Clearly, damage to the orbitofrontal cortex does impair pleasure-related decisions, including choices and context-related cognitions in humans, monkeys, and rats ( Anderson et al. 1999 ; Nauta 1971 ). But some caution regarding whether the cortex generates positive affect states per se is indicated by the consideration that patients with lesions to the orbitofrontal cortex do still react normally to many pleasures, although sometimes showing inappropriate emotions. Hedonic capacity after prefrontal damage has not, however, yet been studied in careful enough detail to draw firm conclusions about cortical causation (for example, using selective satiation paradigms), and it would be useful to have more information on the role of orbitofrontal cortex, insular cortex, and cingulate cortex in generating and modulating hedonic states.

Pleasure causation has been so far rather difficult to assess in humans given the limits of information from lesion studies, and the correlative nature of neuroimaging studies. A promising tool, however, is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is a versatile and reversible technique that directly alters brain activity in a brain target and where the ensuing whole-brain activity can be measured with Magnetoencephalography (MEG) ) Kringelbach et al. 2007 ). Pertinent to a view of happiness as freedom from distress, at least pain relief can be obtained from DBS of periaqueductal grey in the brainstem in humans, where specific neural signatures of pain have been found ( Green et al. 2009 ), and where the pain relief is associated with activity in the midanterior orbitofrontal cortex, perhaps involving endogenous opioid release. Similarly, DBS may alleviate some unpleasant symptoms of depression, though without actually producing positive affect.

Famously, also, pleasure electrodes were reported to exist decades ago in animals and humans when implanted in subcortical structures, including the nucleus accumbens, septum and medial forebrain bundle ( Olds and Milner 1954 ; Heath 1972 ) ( figure 2c ). However, recently we and others have questioned whether most such electrodes truly caused pleasure, or instead, only a psychological process more akin to “wanting” without “liking” ( Berridge and Kringelbach 2008 ). In our view, it still remains unknown whether DBS causes true pleasure, or if so, where in the brain electrodes produce it.

LOSS OF PLEASURE

The lack of pleasure, anhedonia, is one of the most important symptoms of many mental illnesses, including depression. It is difficult to conceive of anyone reporting happiness or well-being while so deprived of pleasure. Thus anhedonia is another potential avenue of evidence for the link between pleasure and happiness.

The brain regions necessary for pleasure—but disrupted in anhedonia—are not yet fully clear. Core “liking” reactions to sensory pleasures appear relatively difficult to abolish absolutely in animals by a single brain lesion or drug, which may be very good in evolutionary terms. Only the ventral pallidum has emerged among brain hedonic hotspots as a site where damage fully abolishes the capacity for positive hedonic reaction in rodent studies, replacing even “liking” for sweetness with “disliking” gapes normally reserved for bitter or similarly noxious tastes, at least for a while ( Aldridge and Berridge 2010 ). Interestingly, there are extensive connections from the ventral pallidum to the medial orbitofrontal cortex.

On the basis of this evidence, the ventral pallidum might also be linked to human anhedonia. This brain region has not yet been directly surgically targeted by clinicians but there is anecdotal evidence that some patients with pallidotomies (of nearby globus pallidus, just above and behind the ventral pallidum) for Parkinson’s patients show flattened affect (Aziz, personal communication), and stimulation of globus pallidus internus may help with depression. A case study has also reported anhedonia following bilateral lesion to the ventral pallidum ( Miller et al. 2006 ).

Alternatively, core “liking” for fundamental pleasures might persist intact but unacknowledged in anhedonia, while instead only more cognitive construals, including retrospective or anticipatory savoring, becomes impaired. That is, fundamental pleasure may not be abolished in depression after all. Instead, what is called anhedonia might be secondary to motivational deficits and cognitive misap-praisals of rewards, or to an overlay of negative affective states. This may still disrupt life enjoyment, and perhaps render higher pleasures impossible.

Other potential regions targeted by DBS to help with depression and anhedonia include the nucleus accumbens and the subgenual cingulate cortex. In addition, lesions of the posterior part of the anterior cingulate cortex have been used for the treatment of depression with some success ( Steele et al. 2008 ).

BRIDGING PLEASURE TO MEANING

It is potentially interesting to note that all these structures either have close links with frontal cortical structures in the hedonic network (for example, nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum) or belong to what has been termed the brain’s default network, which changes over early development ( Fransson et al. 2007 ; Fair et al. 2008 ).

Mention of the default network brings us back to the topic of eudaimonic happiness, and to potential interactions of hedonic brain circuits with circuits that assess meaningful relationships of self to social others. The default network is a steady state circuit of the brain, which becomes perturbed during cognitive tasks ( Gusnard and Raichle 2001 ). Most pertinent here is an emerging literature that has proposed the default network to carry representations of self ( Lou et al. 1999 ), internal modes of cognition ( Buckner et al. 2008 ), and perhaps even states of consciousness ( Laureys et al. 2004 ). Such functions might well be important to higher pleasures as well as meaningful aspects of happiness.

Although highly speculative, we wonder whether the default network might deserve further consideration for a role in connecting eudaimonic and hedonic happiness. At least, key regions of the frontal default network overlap with the hedonic network discussed above, such as the anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices, and have a relatively high density of opiate receptors. And activity changes in the frontal default network, such as in the subgenual cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices, correlate to pathological changes in subjective hedonic experience, such as in depressed patients ( Drevets et al. 1997 ).

Pathological self-representations by the frontal default network could also provide a potential link between hedonic distortions of happiness that are accompanied by eudaimonic dissatisfaction, such as in cognitive rumination of depression. Conversely, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression, which aims to disengage from dysphoria-activated depressogenic thinking, might conceivably recruit default network circuitry to help mediate improvement in happiness via a linkage to hedonic circuitry.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The most difficult questions facing pleasure and happiness research remain the nature of its subjective experience, the relation of hedonic components (pleasure or positive affect) to eudaimonic components (cognitive appraisals of meaning and life satisfaction), and the relation of each of these components to underlying brain systems. While some progress has been made in understanding brain hedonics, it is important not to over-interpret. In particular we have still not made substantial progress toward understanding the functional neuroanatomy of happiness.

In this article, we have identified a number of brain regions that are important in the brain’s hedonic networks, and speculated on the potential interaction of hedonics with eudaimonic networks. So far the most distinctive insights have come from studying sensory pleasures, but another challenge is to understand the how brain networks underlying fundamental pleasure relate to higher pleasures, such as music, dance, play, and flow to contribute to happiness. While it remains unclear how pleasure and happiness are exactly linked, it may be safe to say at least that the pathological lack of pleasure, in anhedonia or dysphoria, amounts to a formidable obstacle to happiness.

Further, in social animals like humans, it is worth noting that social interactions with conspecifics are fundamental and central to enhancing the other pleasures. Humans are intensely social, and data indicate that one of the most important factors for happiness is social relationships with other people. Social pleasures may still include vital sensory features such as visual faces, touch features of grooming and caress, as well as in humans more abstract and cognitive features of social reward and relationship evaluation. These may be important triggers for the brain’s hedonic networks in human beings.

In particular, adult pair bonds and attachment bonds between parents and infants are likely to be extremely important for the survival of the species ( Kringelbach et al. 2008 ). The breakdown of these bonds is all too common and can lead to great unhappiness. And even bond formation can potentially disrupt happiness, such as in transient parental depression after birth of an infant (in over 10 percent of mothers and approximately 3 percent of fathers [ Cooper and Murray 1998 ]). Progress in understanding the hedonics of social bonds could be useful in understanding happiness, and it will be important to map the developmental changes that occur over a lifespan. Fortunately, social neuroscience is beginning to unravel some of the complex dynamics of human social interactions and their relation to brain activations ( Parsons et al. 2010 ).

In conclusion, so far as positive affect contributes to happiness, then considerable progress has been made in understanding the neurobiology of pleasure in ways that might be relevant. For example, we can imagine several possibilities to relate happiness to particular hedonic psychological processes discussed above. Thus, one way to conceive of hedonic happiness is as “liking” without “wanting.” That is, a state of pleasure without disruptive desires, a state of contentment ( Kringelbach 2009 ). Another possibility is that moderate “wanting,” matched to positive “liking,” facilitates engagement with the world. A little incentive salience may add zest to the perception of life and perhaps even promote the construction of meaning, just as in some patients therapeutic deep brain stimulation may help lift the veil of depression by making life events more appealing. However, too much “wanting” can readily spiral into maladaptive patterns such as addiction, and is a direct route to great unhappiness. Finally, happiness of course springs not from any single component but from the interplay of higher pleasures, positive appraisals of life meaning and social connectedness, all combined and merged by interaction between the brain’s default networks and pleasure networks. Achieving the right hedonic balance in such ways may be crucial to keep one not just ticking over but actually happy.

Future scientific advances may provide a better sorting of psychological features of happiness and its underlying brain networks. If so, it remains a distinct possibility that more among us may be one day shifted into a better situation to enjoy daily events, to find life meaningful and worth living—and perhaps even to achieve a degree of bliss.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Peterson, Eric Jackson, Kristine Rømer Thomsen, Christine Parsons, and Katie Young for helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Our research has been supported by grants from the TrygFonden Charitable Foundation to Kringelbach and from the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse to Berridge.

- Aldridge JW, Berridge KC. Neural Coding of Pleasure: ‘Rose-Tinted Glasses’ of the Ventral Pallidum. In: Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC, editors. Pleasures of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 62–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson SW, et al. Impairment of Social and Moral Behavior Related to Early Damage in Human Prefrontal Cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2(11):1032–37. doi: 10.1038/14833. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berridge Kent. The Debate over Dopamine’s Role in Reward: The Case for Incentive Salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191(3):391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML. Affective Neuroscience of Pleasure: Reward in Humans and Animals. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:457–80. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1099-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berridge Kent C, Robinson Terry E. Parsing Reward. Trends in Neurosciences. 2003;26(9):507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buckner RL, et al. The Brain’s Default Network: Anatomy, Function, and Relevance to Disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper PJ, Murray L. Postnatal Depression. British Medical Journal. 1998;316(7148):1884–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1884. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davidson RJ, Irwin W. The Functional Neuroanatomy of Emotion and Affective Style. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1999;3(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01265-0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drevets WC, et al. Subgenual Prefrontal Cortex Abnormalities in Mood Disorders. Nature. 1997;386(6627):824–7. doi: 10.1038/386824a0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fair DA, et al. The Maturing Architecture of the Brain’s Default Network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(10):4028–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800376105. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fransson P, et al. Resting-State Networks in the Infant Brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(39):15531–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704380104. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fredrickson BL, et al. Open Hearts Build Lives: Positive Emotions, Induced through Loving-Kindness Meditation, Build Consequential Personal Resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(5):1045–62. doi: 10.1037/a0013262. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freud S, Riviere J. Civilization and Its Discontents. New York: J. Cape and H. Smith; 1930. [ Google Scholar ]

- Frijda Nico. On the Nature and Function of Pleasure. In: Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC, editors. Pleasures of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 99–112. [ Google Scholar ]

- Green AL, et al. Neural Signatures in Patients with Neuropathic Pain. Neurology. 2009;72(6):569–71. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000342122.25498.8b. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gusnard DA, Raichle ME. Searching for a Baseline: Functional Imaging and the Resting Human Brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2(10):685–94. doi: 10.1038/35094500. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haisken-De New JP, Frick R. Desktop Companion to the German SocioEconomic Panel Study (Gsoep) Berlin: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW); 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heath RG. Pleasure and Brain Activity in Man. Deep and Surface Electroencephalograms During Orgasm. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1972;154(1):3–18. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197201000-00002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- James W. To Miss Frances R. Morse. Nanheim, July 10, 1901. In: James H, editor. Letters of William James. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press; 1920. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahneman D. Objective Happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwartz N, editors. Well-Being: The Foundation of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 3–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kesebir P, Diener E. In Pursuit of Happiness: Empirical Answers to Philosophical Questions. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00069.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML. Emotion. In: Gregory RL, editor. The Oxford Companion to the Mind. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 287–90. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML. The Human Orbitofrontal Cortex: Linking Reward to Hedonic Experience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6(9):691–702. doi: 10.1038/nrn1747. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML. The Pleasure Center: Trust Your Animal Instincts. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML. The Hedonic Brain: A Functional Neuroanatomy of Human Pleasure. In: Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC, editors. Pleasures of the Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 202–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC. Pleasures of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, et al. Deep Brain Stimulation for Chronic Pain Investigated with Magnetoencephalography. Neuroreport. 2007;18(3):223–28. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328010dc3d. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, et al. A Specific and Rapid Neural Signature for Parental Instinct. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:2. e1664. doi: 10.371/journal.pone.0001664. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET. The Functional Neuroanatomy of the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex: Evidence from Neuroimaging and Neuropsychology. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;72(5):341–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.03.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC. Towards a Functional Neuroanatomy of Pleasure and Happiness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13(11):479–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.08.006. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuppens P, et al. The Role of Positive and Negative Emotions in Life Satisfaction Judgment across Nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(1):66–75. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.66. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laureys S, et al. Brain Function in Coma, Vegetative State, and Related Disorders. Lancet Neurology. 2004;3(9):537–46. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00852-X. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lou HC, et al. A 15O-H2O PET Study of Meditation and the Resting State of Normal Consciousness. Human Brain Mapping. 1999;7(2):98–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)7:2<98::AID-HBM3>3.0.CO;2-M. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller JM, et al. Anhedonia after a Selective Bilateral Lesion of the Globus Pallidus. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):786–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.786. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nauta WJ. The Problem of the Frontal Lobe: A Reinterpretation. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1971;8(3):167–87. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(71)90017-3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nesse RM. Natural Selection and the Elusiveness of Happiness. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 2004;359(1449):1333–47. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1511. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Doherty J, et al. Abstract Reward and Punishment Representations in the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(1):95–102. doi: 10.1038/82959. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oishi S, et al. The Optimal Level of Well-Being: Can We Be Too Happy? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2:346–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00048.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olds J, Milner P. Positive Reinforcement Produced by Electrical Stimulation of Septal Area and Other Regions of Rat Brain. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1954;47:419–27. doi: 10.1037/h0058775. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parsons CE, et al. The Functional Neuroanatomy of the Evolving Parent-Infant Relationship. Progress in Neurobiology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.03.001. forthcoming. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The Neural Basis of Drug Craving: An Incentive-Sensitization Theory of Addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18(3):247–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seligman ME, et al. Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. American Psychologist. 2005;60(5):410–21. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith KS, et al. Hedonic Hotspots: Generating Sensory Pleasure in the Brain. In: Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC, editors. Pleasures of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 27–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steele JD, et al. Anterior Cingulotomy for Major Depression: Clinical Outcome and Relationship to Lesion Characteristics. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(7):670–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.019. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinbeck J, Ricketts EF. The Log from the Sea of Cortez. London: Penguin; 1941. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steiner JE, et al. Comparative Expression of Hedonic Impact: Affective Reactions to Taste by Human Infants and Other Primates. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2001;25(1):53–74. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00051-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- PDF (566.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The art of happiness: an explorative study of a contemplative program for subjective well-being.

- 1 Department of Psychology and Cognitive Science, University of Trento, Trento, Italy

- 2 Department of Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 3 Institute Lama Tzong Khapa, Pisa, Italy

In recent decades, psychological research on the effects of mindfulness-based interventions has greatly developed and demonstrated a range of beneficial outcomes in a variety of populations and contexts. Yet, the question of how to foster subjective well-being and happiness remains open. Here, we assessed the effectiveness of an integrated mental training program The Art of Happiness on psychological well-being in a general population. The mental training program was designed to help practitioners develop new ways to nurture their own happiness. This was achieved by seven modules aimed at cultivating positive cognition strategies and behaviors using both formal (i.e., lectures, meditations) and informal practices (i.e., open discussions). The program was conducted over a period of 9 months, also comprising two retreats, one in the middle and one at the end of the course. By using a set of established psychometric tools, we assessed the effects of such a mental training program on several psychological well-being dimensions, taking into account both the longitudinal effects of the course and the short-term effects arising from the intensive retreat experiences. The results showed that several psychological well-being measures gradually increased within participants from the beginning to the end of the course. This was especially true for life satisfaction, self-awareness, and emotional regulation, highlighting both short-term and longitudinal effects of the program. In conclusion, these findings suggest the potential of the mental training program, such as The Art of Happiness , for psychological well-being.

Introduction

People desire many valuable things in their life, but—more than anything else—they want happiness ( Diener, 2000 ). The sense of happiness has been conceptualized as people's experienced well-being in both thoughts and feelings ( Diener, 2000 ; Kahneman and Krueger, 2006 ). Indeed, research on well-being suggests that the resources valued by society, such as mental health ( Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., 2004 ) and a long life ( Danner et al., 2001 ), associate with high happiness levels. Since the earliest studies, subjective well-being has been defined as the way in which individuals experience the quality of their life in three different but interrelated mental aspects: infrequent negative affect, frequent positive affect, and cognitive evaluations of life satisfaction in various domains (physical health, relationships, and work) ( Diener, 1984 , 1994 , 2000 ; Argyle et al., 1999 ; Diener et al., 1999 ; Lyubomksky et al., 2005 ; Pressman and Cohen, 2005 ). A growing body of research has been carried out aimed at identifying the factors that affect happiness, operationalized as subjective well-being. In particular, the construct of happiness is mainly studied within the research fields of positive psychology or contemplative practices, which are grounded in ancient wisdom traditions. Positive psychology has been defined as the “the scientific study of human strengths and virtues” ( Sheldon and King, 2001 ), and it can be traced back to the reflections of Aristotle about different perspectives on well-being ( Ryan and Deci, 2001 ). On the other end, contemplative practices include a great variety of mental exercises, such as mindfulness, which has been conceived as a form of awareness that emerges from experiencing the present moment without judging those experiences ( Kabat-Zinn, 2003 ; Bishop et al., 2004 ). Most of these exercises stem from different Buddhist contemplative traditions such as Vipassana and Mahayana ( Kornfield, 2012 ). Notably, both perspective share the idea of overcoming suffering and achieving happiness ( Seligman, 2002 ). Particularly, Buddhism supports “the cultivation of happiness, genuine inner transformation, deliberately selecting and focusing on positive mental states” ( Lama and Cutler, 2008 ). In addition, mindfulness has been shown to be positively related to happiness ( Shultz and Ryan, 2015 ), contributing to eudemonic and hedonic well-being ( Howell et al., 2011 ).

In fact, although the definition of happiness has a long history and goes back to philosophical arguments and the search for practical wisdom, in modern times, happiness has been equated with hedonism. It relies on the achievement of immediate pleasure, on the absence of negative affect, and on a high degree of satisfaction with one's life ( Argyle et al., 1999 ). Nonetheless, scholars now argue that authentic subjective well-being goes beyond this limited view and support an interpretation of happiness as a eudemonic endeavor ( Ryff, 1989 ; Keyes, 2006 ; Seligman, 2011 ; Hone et al., 2014 ). Within this view, individuals seem to focus more on optimal psychological functioning, living a deeply satisfying life and actualizing their own potential, personal growth, and a sense of autonomy ( Deci and Ryan, 2008 ; Ryff, 2013 ; Vazquez and Hervas, 2013 ; Ivtzan et al., 2016 ). In psychology, such a view finds one of its primary supports in Maslow's (1981) theory of human motivation. Maslow argued that experience of a higher degree of satisfaction derives from a more wholesome life conduct. In Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory, once lower and more localized needs are satisfied, the unlimited gratification of needs at the highest level brings people to a full and deep experience of happiness ( Inglehart et al., 2008 ). Consequently, today, several scholars argue that high levels of subjective well-being depend on a multi-dimensional perspective, which encompasses both hedonic and eudemonic components ( Huta and Ryan, 2010 ; Ryff and Boylan, 2016 ). Under a wider perspective, the process of developing well-being reflects the notion that mental health and good functioning are more than a lack of illness ( Keyes, 2005 ). This approach is especially evident if we consider that even the definition of mental health has been re-defined by the World Health Organization (1948) , which conceives health not merely as the absence of illness, but as a whole state of biological, psychological, and social well-being.

To date, evidence exists suggesting that happiness is, in some extent, modulable and trainable. Thus, simple cognitive and behavioral strategies that individuals choose in their lives could enhance happiness ( Lyubomirsky et al., 2005 ; Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009 ). In the history of psychology, a multitude of clinical treatments have been applied to minimize the symptoms of a variety of conditions that might hamper people from being happy, such as anger, anxiety, and depression (for instance, see Forman et al., 2007 ; Spinhoven et al., 2017 ). In parallel with this view, an alternative—and less developed—perspective found in psychology focuses on the scientific study of individual experiences and positive traits, not for clinical ends, but instead for personal well-being and flourishing (e.g., Fredrickson and Losada, 2005 ; Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009 ). Yet, the question of exactly how to foster subjective well-being and happiness, given its complexity and importance, remains open to research. Answering this question is of course of pivotal importance, both individually and at the societal level. Positive Psychology Interventions encompass simple, self-administered cognitive behavioral strategies intended to reflect the beliefs and behaviors of individuals and, in response to that, to increase the happiness of the people practicing them ( Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009 ; Hone et al., 2015 ). Specifically, a series of comprehensive psychological programs to boost happiness exist, such as Fordyce's program ( Fordyce, 1977 ), Well-Being Therapy ( Fava, 1999 ), and Quality of Life Therapy ( Frisch, 2006 ). Similarly, a variety of meditation-based programs aim to develop mindfulness and emotional regulatory skills ( Carmody and Baer, 2008 ; Fredrickson et al., 2008 ; Weytens et al., 2014 ), such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1990 ) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Teasdale et al., 2000 ). Far from being a mere trend ( De Pisapia and Grecucci, 2017 ), those mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to lead to increased well-being ( Baer et al., 2006 ; Keng et al., 2011 ; Choi et al., 2012 ; Coo and Salanova, 2018 ; Lambert et al., 2019 ) in several domains, such as cognition, consciousness, self, and affective processing ( Raffone and Srinivasan, 2017 ). Typically, mindfulness programs consist of informal and formal practice that educate attention and develop one's capacity to respond to unpredicted and/or negative thoughts and experiences ( Segal and Teasdale, 2002 ). In this context, individuals are gradually introduced to meditation practices, focusing first on the body and their own breath, and later on thoughts and mental states. The effects of these programs encompass positive emotions and reappraisal ( Fredrickson et al., 2008 ; Grecucci et al., 2015 ; Calabrese and Raffone, 2017 ) and satisfaction in life ( Fredrickson et al., 2008 ; Kong et al., 2014 ) and are related to a reduction of emotional reactivity to negative affect, stress ( Arch and Craske, 2006 ; Jha et al., 2017 ), and aggressive behavior ( Fix and Fix, 2013 ). All these effects mediate the relationship between meditation frequency and happiness ( Campos et al., 2016 ). This allows positive psychology interventions to improve subjective well-being and happiness and also reduce depressive symptoms and negative affect along with other psychopathologies ( Seligman, 2002 ; Quoidbach et al., 2015 ). Engaging in mindfulness might enhance in participants the awareness of what is valuable to them ( Shultz and Ryan, 2015 ). This aspect has been related to the growth of self-efficacy and autonomous functioning and is attributable to an enhancement in eudemonic well-being ( Deci and Ryan, 1980 ). Moreover, being aware of the present moment provides a clearer vision of the existing experience, which in turn has been associated with increases in hedonic well-being ( Coo and Salanova, 2018 ). Following these approaches, recent research provides evidence that trainings that encompass both hedonic and eudemonic well-being are correlated with tangible improved health outcomes ( Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009 ).

Although there is a consistent interest in scientific research on the general topic of happiness, such studies present several limitations. Firstly, most of the research has focused on clinical studies to assess the effectiveness of happiness-based interventions—in line with more traditional psychological research, which is primarily concerned with the study of mental disorders ( Garland et al., 2015 , 2017 ; Groves, 2016 ). Secondly, most of the existing interventions are narrowly focused on the observation of single dimensions (i.e., expressing gratitude or developing emotional regulation skills) ( Boehm et al., 2011 ; Weytens et al., 2014 ). Moreover, typically studies involve brief 1- to 2-week interventions ( Gander et al., 2016 ), in contrast with the view that eudemonia is related to deep and long-lasting aspects of one's personal lifestyle. Furthermore, while the effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies is well-documented, research that investigates the effects of mindfulness retreats has been lacking, which are characterized by the involvement of more intense practice from days to even years [for meta-analysis and review, see Khoury et al. (2017) , McClintock et al. (2019) , Howarth et al. (2019) ].

In this article, we report the effects on subjective well-being of an integrated mental training program called The Art of Happiness , which was developed and taught by two of the authors (CM for the core course subject matter and NDP for the scientific presentations). The course lasted 9 months and included three different modules (see Methods and Supplementary Material for all details), namely, seven weekends (from Friday evening to Sunday afternoon) dedicated to a wide range of specific topics, two 5-day long retreats, and several free activities at home during the entire period. The course was designed to help practitioners develop new ways to nurture their own happiness, cultivating both self-awareness and their openness to others, thereby fostering their own emotional and social well-being. The basic idea was to let students discover how the union of ancient wisdom and spiritual practices with scientific discoveries from current neuropsychological research can be applied beneficially to their daily lives. This approach and mental training program was inspired by a book of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso and the psychiatrist Lama and Cutler (2008) . The program rests on the principle that happiness is inextricably linked to the development of inner equilibrium, a kinder and more open perspective of self, others, and the world, with a key role given to several types of meditation practices. Additionally, happiness is viewed as linked to a conceptual understanding of the human mind and brain, as well as their limitations and potentiality, in the light of the most recent scientific discoveries. To this end, several scientific topics and discoveries from neuropsychology were addressed in the program, with a particular focus on cognitive, affective, and social neuroscience. Topics were taught and discussed with language suitable for the general public, in line with several recent books (e.g., Hanson and Mendius, 2011 ; Dorjee, 2013 ; Goleman and Davidson, 2017 ). The aim of this study was to examine how several psychological measures, related to psychological well-being, changed among participants in parallel with course attendance and meditation practices. Given the abovementioned results of the positive effects on well-being ( Baer et al., 2006 ; Fredrickson et al., 2008 ; Keng et al., 2011 ; Choi et al., 2012 ; Kong et al., 2014 ; Coo and Salanova, 2018 ; Lambert et al., 2019 ), we predicted to find a significant increase in the dimensions of life satisfaction, control of anger, and mindfulness abilities. Conversely, we expected to observe a reduction of negative emotions and mental states ( Arch and Craske, 2006 ; Fix and Fix, 2013 ; Jha et al., 2017 )—i.e., stress, anxiety and anger. Moreover, our aim was to explore how those measures changed during the course of the mental training program, considering not only the general effects of the course (longitudinal effects) but also specific effects within each retreat (short-term effects). Our expectation for this study was therefore that the retreats would have had an effect on the psychological dimensions of well-being linked to the emotional states of our participants, while the whole course would have had a greater effect on the traits related to well-being. The conceptual distinction between states and traits was initially introduced in regard to anxiety by Cattell and Scheier (1961) , and then subsequently further elaborated by Spielberger et al. (1983) . When considering a mental construct (e.g., anxiety or anger), we refer to trait as a relatively stable feature, a general behavioral attitude, which reflects the way in which a person tends to perceive stimuli and environmental situations in the long term ( Spielberger et al., 1983 ; Spielberger, 2010 ). For example, subjects with high trait anxiety have indeed anxiety as a habitual way of responding to stimuli and situations. The state, on the other hand, can be defined as a temporary phase within the emotional continuum, which, for example, in anxiety is expressed through a subjective sensation of tension, apprehension, and nervousness, and is associated with activation of the autonomic nervous system in the short term ( Spielberger et al., 1983 ; Saviola et al., 2020 ). Here, in the adopted tests and analyses, we keep the two time scales separated, and we investigate the results with the aim of understanding the effects of the program on states and traits of different emotional and well-being measures. As a first effect of the course, we expect that the retreats affect mostly psychological states (as measured in the comparison of psychological variables between start and end of each retreat), whereas the full course is predicted to affect mainly psychological traits (as measured in the comparison of the psychological variables between start, middle, and end of the entire 9-month period).

Materials and Methods

Participants.

The participants in the mental training program and in the related research were recruited from the Institute Lama Tzong Khapa (Pomaia, Italy) in a 9-month longitudinal study (seven modules and two retreats) on the effects of a program called The Art of Happiness (see Supplementary Material for full details of the program). Twenty-nine participants followed the entire program (there were nine dropouts after the first module). Their mean age was 52.86 years (range = 39–66; SD = 7.61); 72% were female. Participants described themselves as Caucasian, reaching a medium-high scholarly level with 59% of the participants holding an academic degree and 41% holding a high school degree. The participants were not randomly selected, as they were volunteers in the program. Most of them had no serious prior experience of meditation, only basic experience consisting of personal readings or watching video courses on the web, which overall we considered of no impact to the study. The only exclusion criteria were absence of a history of psychiatric or neurological disease, and not being currently on psychoactive medications. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sapienza University of Rome, and all participants gave written informed consent. The participants did not receive any compensation for participation in the study.

The overall effectiveness of the 9-month training was examined using a within-subjects design, with perceived stress, mindfulness abilities, etc. (Time: pre–mid–end) as the dependent variable. The effectiveness of the retreats was examined using a 2 × 2 factor within-subjects design (condition: pre vs. post; retreat: 1 vs. 2), with the same dependent variables. The specific contemplative techniques that were applied in the program are described in the Supplementary Material , the procedure is described in the Procedure section, and the measurements are described in the Materials section.

Mental Training Program

The program was developed and offered at the Institute Lama Tzong Khapa (Pomaia, Italy). It was one of several courses that are part of the Institute's ongoing programs under the umbrella of “Secular Ethics and Universal Values.” These various programs provide participants with opportunities to discover how the interaction of ancient wisdom and spiritual practices with contemporary knowledge from current scientific research in neuropsychology can be applied extensively and beneficially to improve the quality of their daily lives.

Specifically, The Art of Happiness was a 9-month program, with one program activity each month, either a weekend module or a retreat; there were two retreats—a mid-course retreat and a concluding retreat (for full details on the program, see Supplementary Material ). Each thematic module provided an opportunity to sequentially explore the topics presented in the core course text, The Art of Happiness by the Lama and Cutler (2008) .

In terms of the content of this program, as mentioned above, the material presented and explored has been drawn on the one hand from the teachings of Mahayana Buddhism and Western contemplative traditions, and current scientific research found in neuropsychology on the other hand. On the scientific side, topics included the effects of mental training and meditation, the psychology and neuroscience of well-being and happiness, neuroplasticity, mind–brain–body interactions, different areas of contemplative sciences, the placebo effects, the brain circuits of attention and mind wandering, stress and anxiety, pain and pleasure, positive and negative emotions, desire and addiction, the sense of self, empathy, and compassion (for a full list of the scientific topics, see Supplementary Material ).

The overall approach of the course was one of non-dogmatic exploration. Topics were presented not as undisputed truths, but instead as information to be shared, explored, examined, and possibly verified by one's own experience. Participants were heartily invited to doubt, explore, and test everything that was shared with them, to examine and experience firsthand whether what was being offered has validity or not.

The course was, essentially, an informed and gentle training of the mind, and in particular of emotions, based on the principle that individual well-being is inextricably linked to the development of inner human virtues and strengths, such as emotional balance, inner self-awareness, an open and caring attitude toward self and others, and clarity of mind that can foster a deeper understanding of one's own and others' reality.

The program provided lectures and discussions, readings, and expert videos introducing the material pertinent to each module's topic. Participants engaged with the material through listening, reading, discussing, and questioning. Participants were provided with additional learning opportunities to investigate each topic more deeply, critically, and personally, through the media of meditation, journaling, application to daily life, exercises at home, and contemplative group work with other participants in dyads and triads. Participants were then encouraged to reflect repeatedly on their insights and on their experiences, both successful and not, to apply their newly acquired understandings to their lives, by incorporating a daily reflection practice into their life schedule. The two program retreats also provided intensive contemplative experiences and activities, both individual and in dialogue with others.

On this basis, month after month in different dedicated modules, participants learned new ways to nurture their own happiness, to cultivate their openness to others, to develop their own emotional and social well-being, and to understand some of the scientific discoveries on these topics.

The specific topics addressed in corresponding modules and retreats, each in a different and consecutive month, were as follows: (1) The Purpose of Life: Authentic Happiness; (2) Empathy and Compassion; (3) Transforming Life's Suffering; (4) Working with Disturbing Emotions I: Hate and Anger; first retreat (intermediate); (5) Working with Disturbing Emotions II: The Self Image; (6) Life and Death; (7) Cultivating the Spiritual Dimension of Life: A Meaningful Life; second retreat (final). Full details of the entire program are reported in the Supplementary Material .

Participants were guided in the theory and practice of various contemplative exercises throughout the course pertaining to all the different themes. Recorded versions of all the various meditation exercises were made available to participants, enabling them to repeat these practices at home at their own pace.

Participants were encouraged to enter the program already having gained some basic experience of meditation, but this was not a strict requirement. In fact, not all participants in this experiment actually fulfilled this (only five), although each of the other participants had previous basic experiences of meditation (through personal readings, other video courses, etc.). In spite of this variety, by the end of the 9-month program, all participants were comfortable with contemplative practices in general and more specifically with the idea of maintaining a meditation practice in their daily lives.

During the various Art of Happiness modules, a variety of basic attentional and mindful awareness meditations were practiced in order to enhance attentional skills and cultivate various levels of cognitive, emotional, social, and environmental awareness.

Analytical and reflective contemplations are a form of deconstructive meditation ( Dahl et al., 2015 ), which were applied during the course in different contexts. On the one hand, these types of meditations were applied in the context of heart-opening practices—for example, in the cultivation of gratitude, forgiveness, loving-kindness toward self and others, self-compassion, and compassion for others. Analytical and reflective meditations were also practiced as a learning tool for further familiarization with some of the more philosophical subject matter of the course—engaging in a contemplative analysis of impermanence (for example, contemplating more deeply and personally the transitory nature of one's own body, of one's own emotions and thoughts, as well as of the material phenomena that surround us). These analytical meditations were also accompanied by moments of concentration (sustained attention) at the conclusion of each meditation focusing on what the meditator has learned or understood in the meditative process, in order to stabilize and reinforce those insights more deeply within the individual.

Additional contemplative activities were also included in the program: contemplative art activities, mindful listening, mindful dialogue, and the practice of keeping silence during the retreat. Participants were, in addition, encouraged to keep a journal of their experiences during their Art of Happiness journey, especially in relation to their meditations and the insights and questions that emerged within themselves, in order to enhance their self-awareness and cultivate a deeper understanding of themselves, their inner life and well-being, and their own inner development during the course and afterward.

During the two retreats, the previous topics were explored again (modules 1–4 for the intermediary retreat and modules 5–7 for the final retreat), but without discussing the theoretical aspects (i.e., the neuroscientific and psychological theories), instead only focusing on the contemplative practices, which were practiced extensively for the whole day, both individually and in group activities (for a full list of the contemplative practices and retreat activities, see Supplementary Material ).

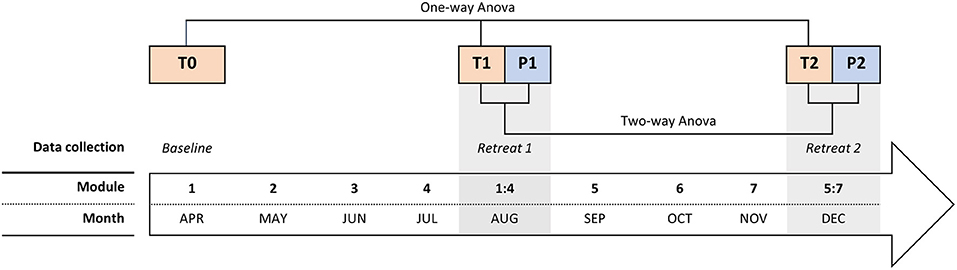

We collected data at five-time points, always during the first day (either of the module or the retreat): at baseline (month 1 - T0), at pre (T1) and post (P1) of the mid-course retreat (month 5–Retreat 1), and at pre (T2) and post (R2) of the final retreat (month 9–Retreat 2), as shown in Figure 1 . Participants filled out the questionnaires on paper all together within the rooms of the Institute Lama Tzong Khapa at the beginning of each module or retreat, and at the end of the retreats, with the presence of two researchers. The order of the questionnaires was randomized, per person and each questionnaire session lasted less than an hour.

Figure 1 . The timing of the course and the experimental procedure, including the modules, the retreats, and the 5 data collections (from T0 to P2).

The adopted questionnaires were those commonly used in the literature to measure a variety of traits and states linked to well-being. An exhaustive description of the self-reported measures follows below.

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS ( Diener et al., 1985 ) was developed to represent cognitive judgments of life satisfaction. Participants indicated their agreement in five items with a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Scores range from 5 to 35, with higher scores representing higher levels of satisfaction. Internal consistency is very good with Cronbach's α = 0.85 [Italian version of the normative data in Di Fabio and Palazzeschi (2012) ].

Short Version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)

The PSS ( Cohen et al., 1983 ) was designed to assess individual perception and reaction to stressful daily-life situations. The questionnaire consists of 10 questions related to the feelings and thoughts of the last month, with a value ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) depending on the severity of the disturbance caused. Scores range from 0 to 40. Higher scores represent higher levels of perceived stress, reflecting the degree to which respondents find their lives unpredictable or overloaded. Cronbach's α ranges from 0.78 to 0.93 [Italian version of the normative data by Mondo et al. (2019) ].

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI ( Spielberger et al., 1983 ) was developed to assess anxiety. It has 40 items, on which respondents evaluate themselves in terms of frequency with a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The items are grouped in two independent subscales of 20 items each that assess state anxiety, with questions regarding the respondents' feelings at the time of administration, and trait anxiety, with questions that explore how the participant feels habitually. The scores range from 20 to 80. Higher scores reflect higher levels of anxiety. Internal consistency coefficients for the scale ranged from 0.86 to 0.95 [Italian version of the normative data by Spielberger et al. (2012) ].

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

PANAS ( Watson et al., 1988 ) measures two distinct and independent dimensions: positive and negative affect. The questionnaire consists of 20 adjectives, 10 for the positive affect subscale and 10 for the negative affect scale. The positive affect subscale reflects the degree to which a person feels enthusiastic, active, and determined while the negative affect subscale refers to some unpleasant general states such as anger, guilt, and fear. The test presents a five-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all; 5 = extremely). The alpha reliabilities are acceptably high, ranging from 0.86 to 0.90 for positive affect and from 0.84 to 0.87 for negative affect [Italian version of the normative data by Terracciano et al. (2003) ].

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

The FFMQ ( Baer et al., 2008 ) was developed to assess mindfulness facets through 39 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). A total of five subscales are included: attention and observation of one's own thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and emotions ( Observe ); the ability to describe thoughts in words, feelings, perceptions, and emotions ( Describe ); act with awareness, with attention focused and sustained on a task or situation, without mind wandering ( Act-aware ); non-judgmental attitude toward the inner experience ( Non-Judge ); and the tendency to not react and not to reject inner experience ( Non-React ). Normative data of the FFMQ have demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach's α ranging from 0.79 to 0.87 [Italian version by Giovannini et al. (2014) ].

State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2)

The STAXI-2 ( Spielberger, 1999 ) provides measures to assess the experience, expression, and control of anger. It comprises 57 items rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much indeed). Items are grouped by four scales: the first, State Anger scale, refers to the emotional state characterized by subjective feelings and relies on three more subscales: Angry Feelings, Physical Expression of Anger, and Verbal Expression of Anger. The second scale is the Trait Anger and indicates a disposition to perceive various situations as annoying or frustrating with two subscales—Angry Temperament and Angry Reaction. The third and last scales are Anger Expression and Anger Control. These assess anger toward the environment and oneself according to four relatively independent subscales: Anger Expression-OUT, Anger Expression-IN, Anger Control-OUT, and Anger Control-IN. Alpha coefficients STAXI-2 were above 0.84 for all scales and subscales, except for Trait Anger Reaction, which had an alpha coefficient of 0.76 [Italian version by Spielberger (2004) ].

Statistical Analysis

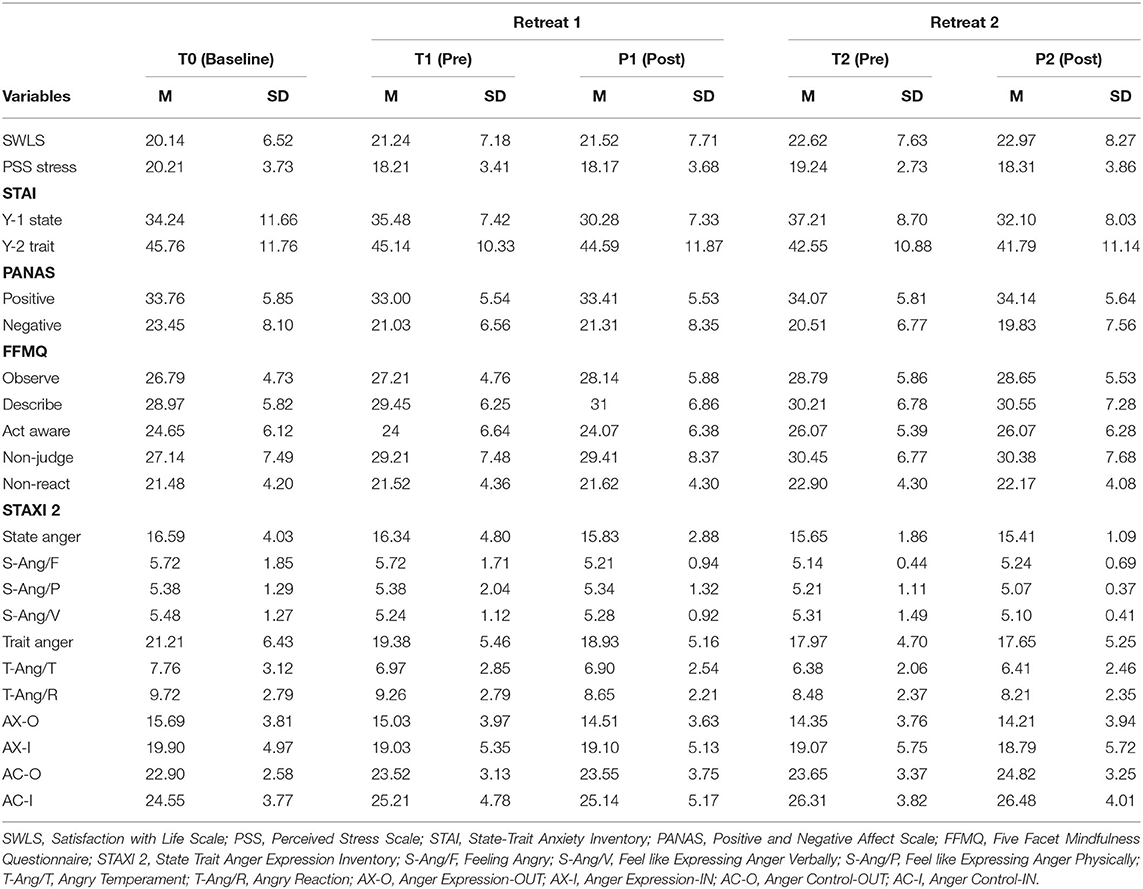

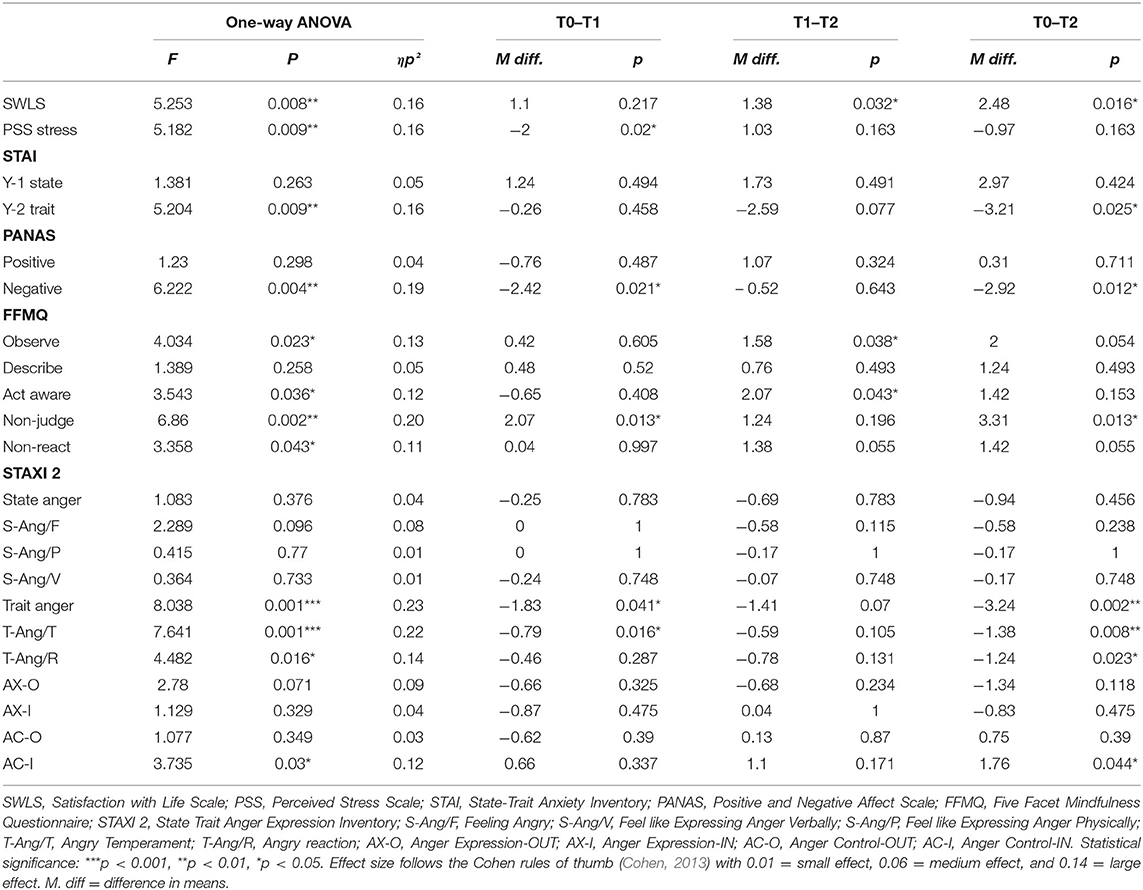

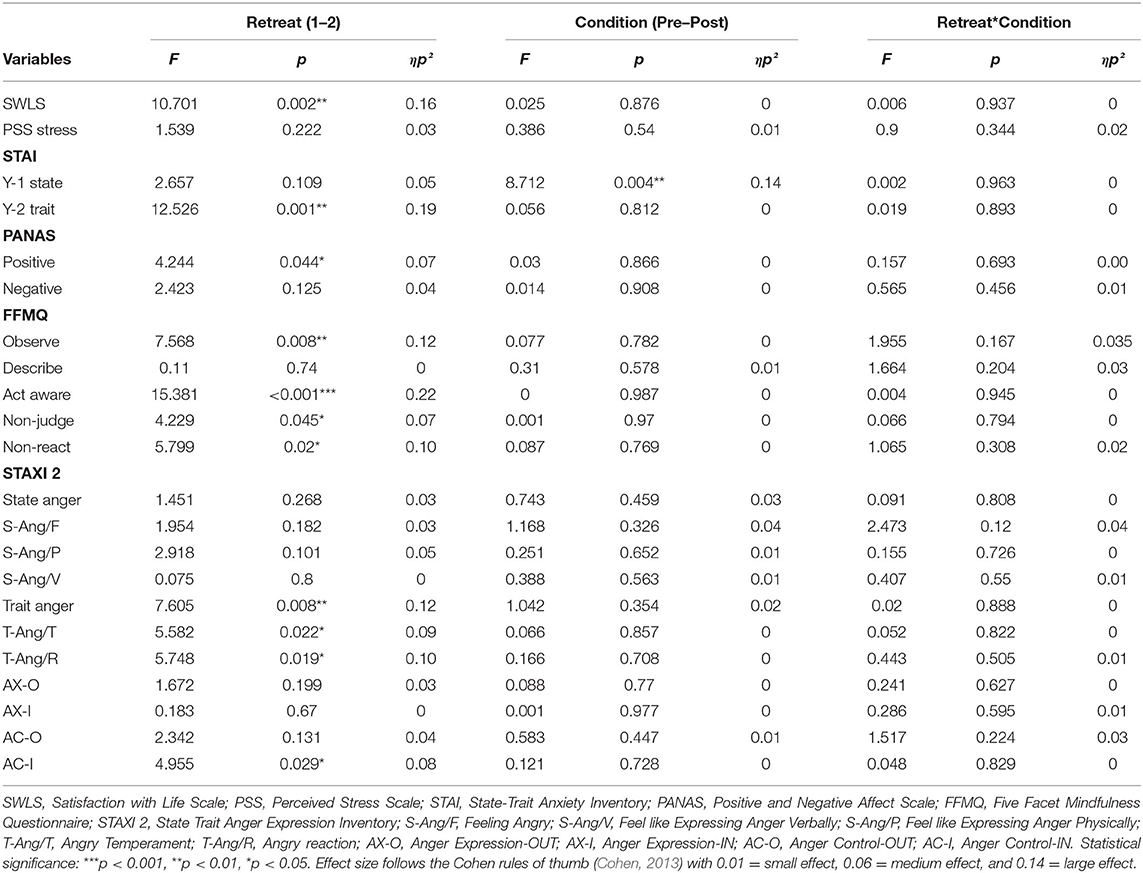

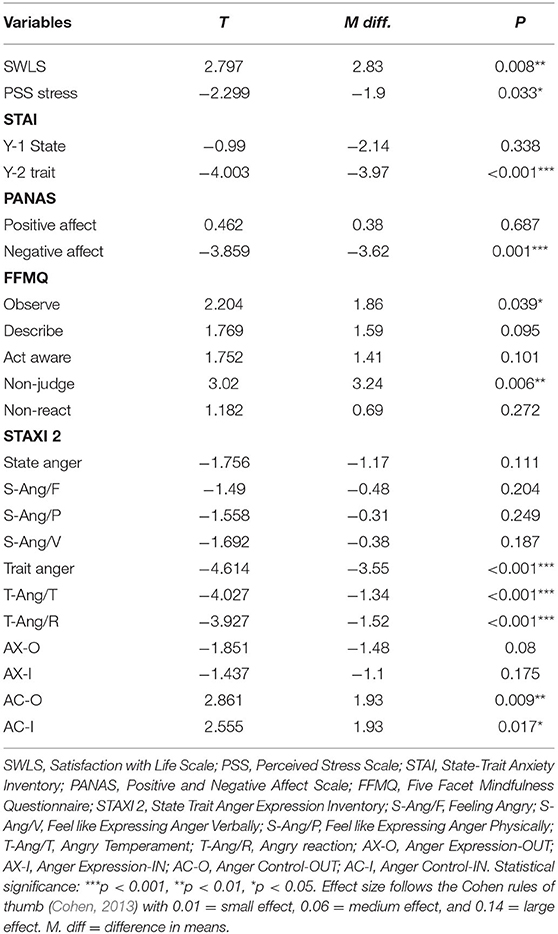

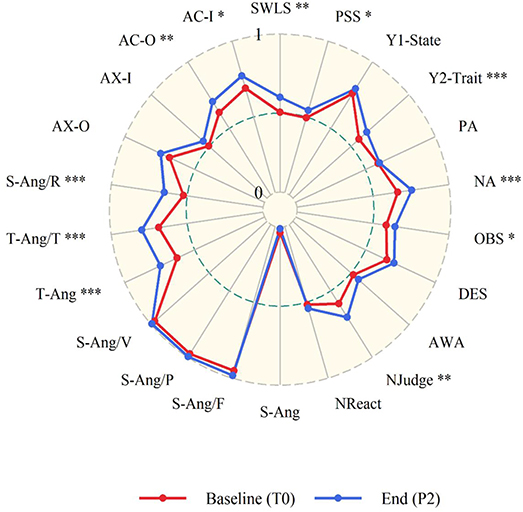

The responses on each questionnaire were scored according to their protocols, which resulted in one score per participant and a time point for each of the 22 scale/subscale questionnaires examined. Missing values (<2%) were imputed using the median. Descriptive statistics for all variables were analyzed and are summarized in Table 1 and in the first panel (column) of Figures 2 – 5 . Prior to conducting primary analyses, the distribution of scores on all the dependent variables was evaluated. Because the data were not normally distributed, we used non-parametric tests. Permutation tests are non-parametric tests as they do not rely on assumptions about the distribution of the data and can be used with different types of scales and with a small sample size.

Table 1 . Descriptive statistics of the depended variables among time points.

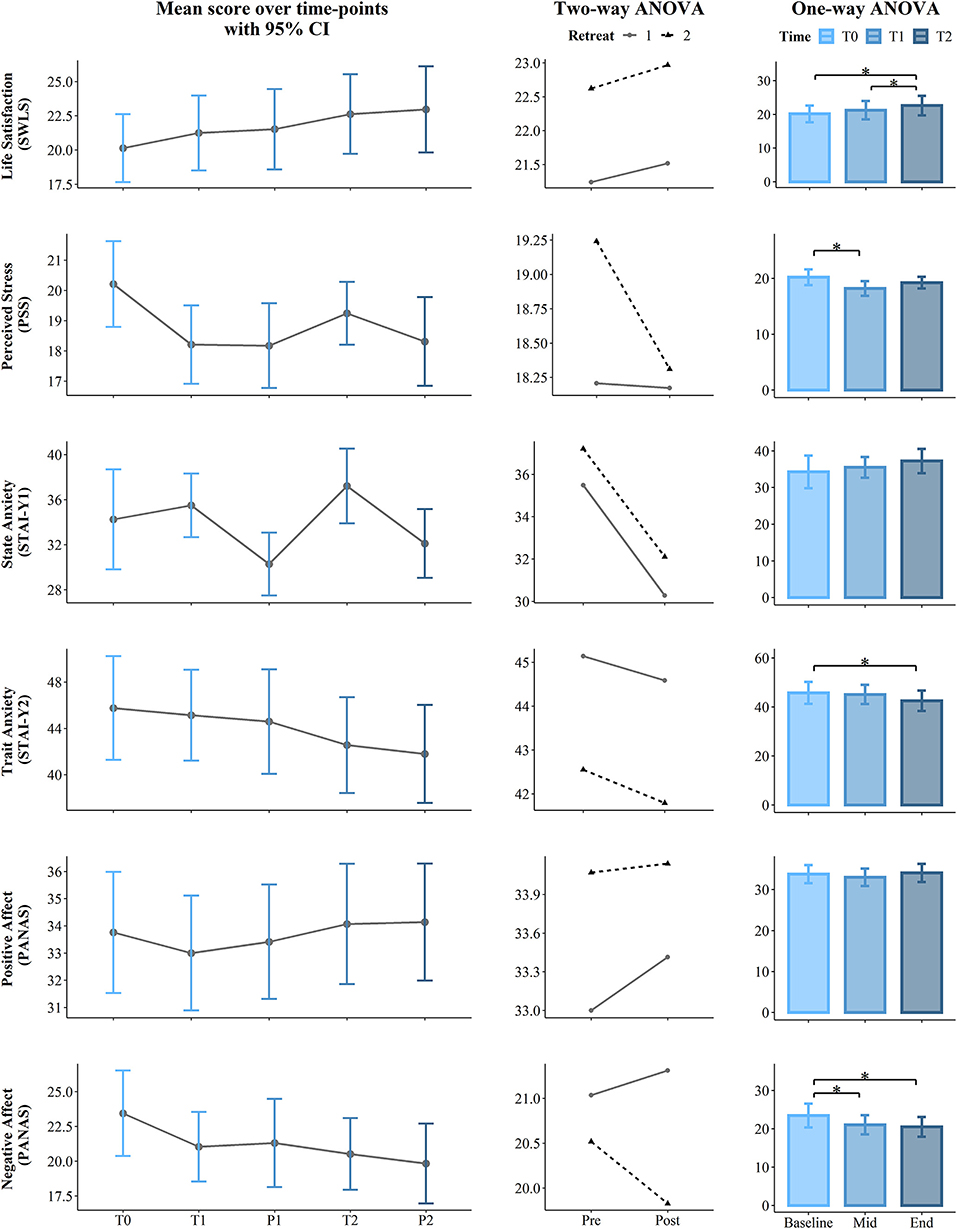

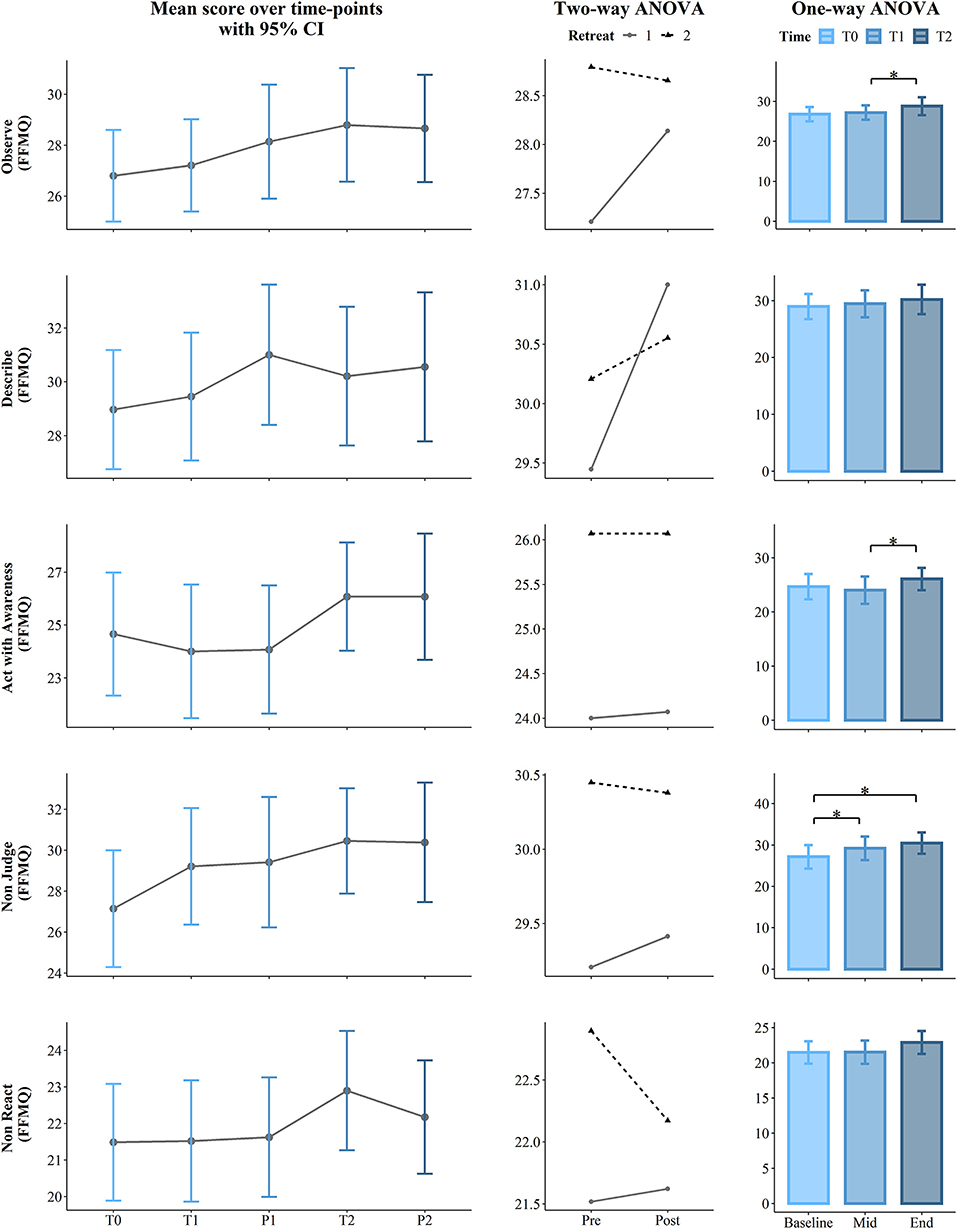

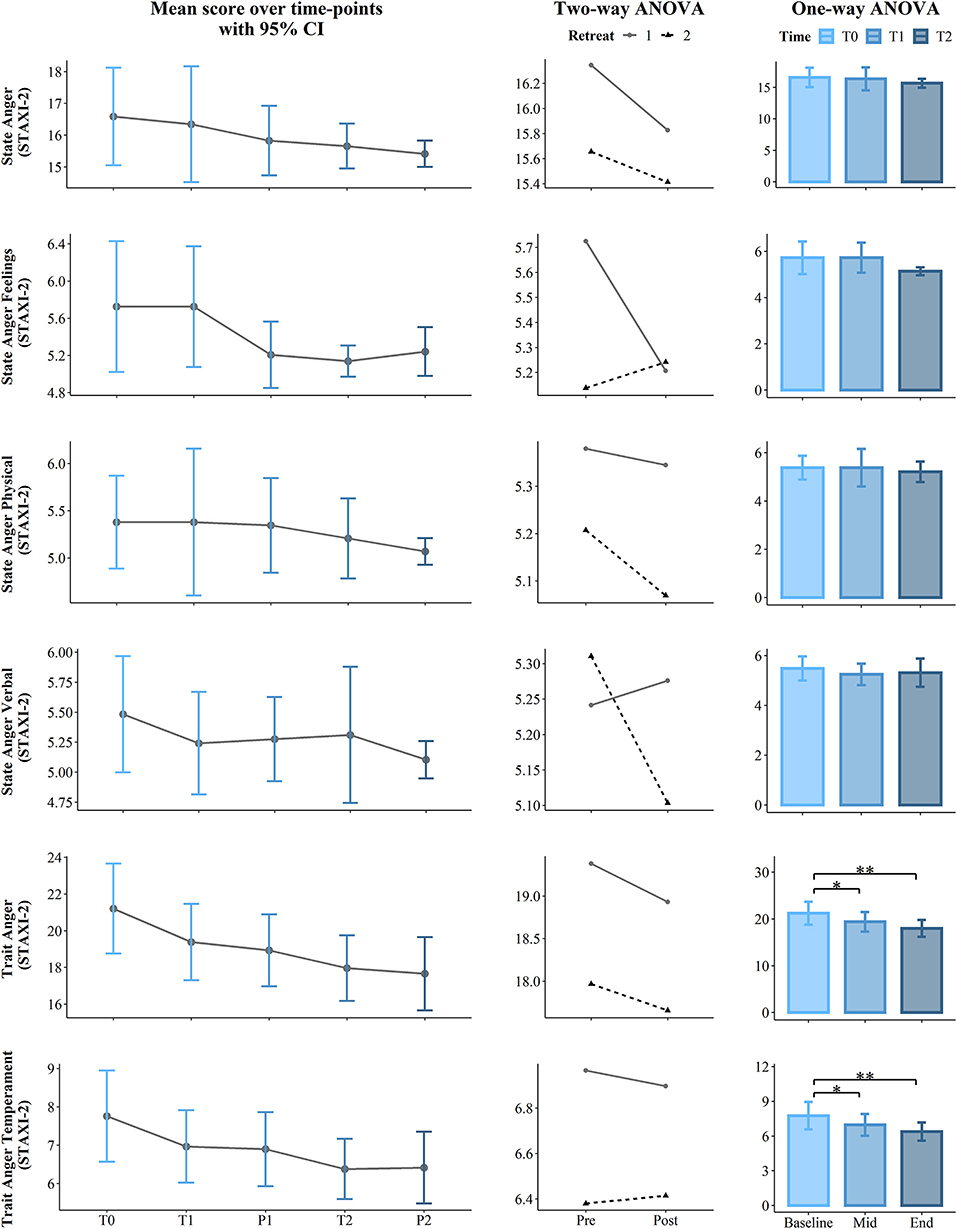

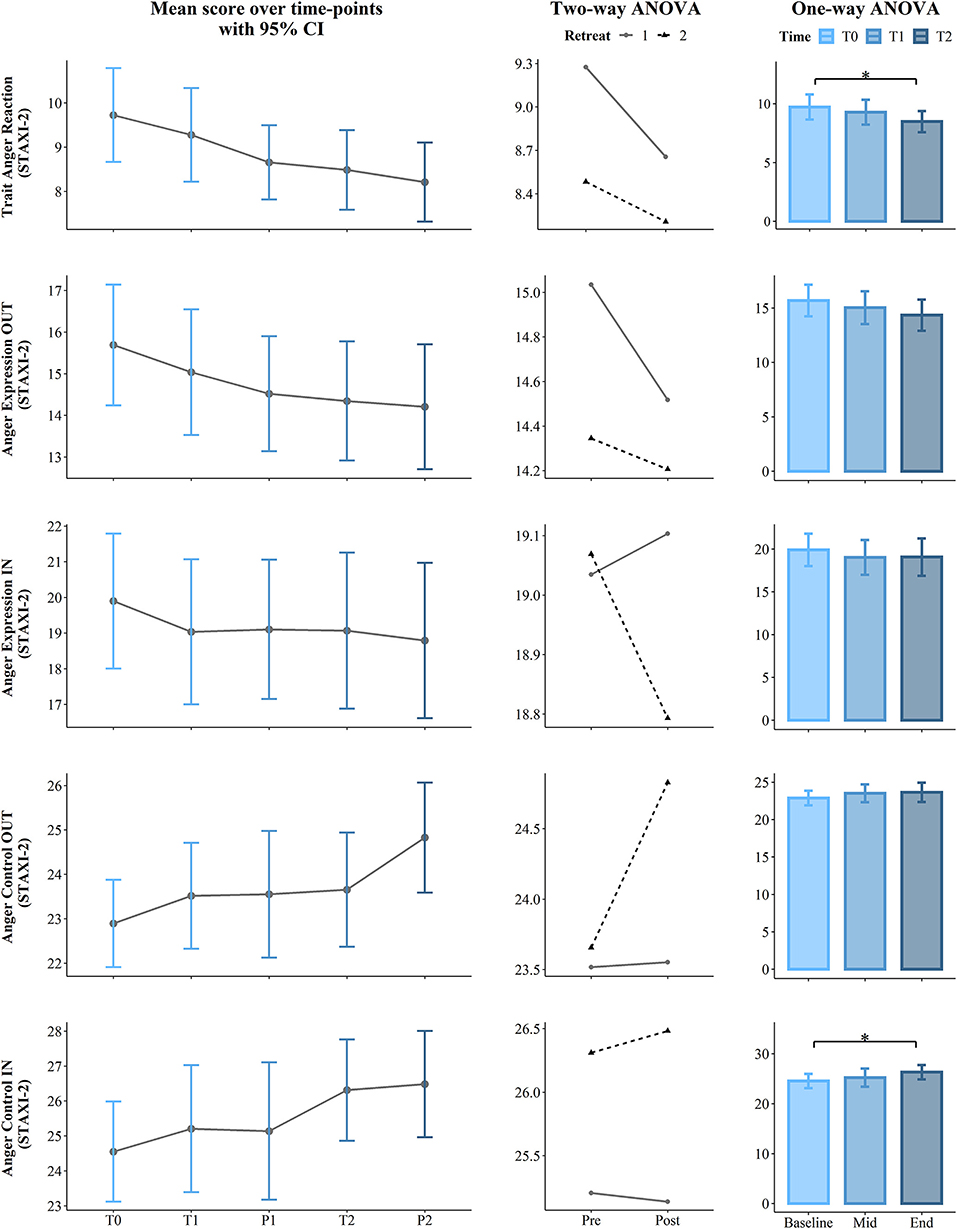

Figure 2 . Results of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), State and Trait Anxiety Index (STAI), and Positive and Negative Affect Scales (PANAS). The first (left) panel depicts pooled mean raw data per time point estimating 95% confidence interval. The second (central) panel represents changes in pooled mean ( y -axis) between retreats. The solid line represents retreat 1 and the dotted line denotes retreat 2 derived from the contrasts of the two-way ANOVA. The third (right) panel depicts bar charts representing the changes in mean between the 3 time points derived from the one-way ANOVA. Note that scores are on the y -axis and time is on the x -axis. Time points legend: baseline (month 1—T0), pre (T1), post (P1), mid-course retreat (month 5—retreat 1), pre (T2), and post (R2) of the final retreat (month 9—retreat 2). Statistical significance, * p < 0.05.