An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Alcohol and substance use among first-year students at the University of Nairobi, Kenya: Prevalence and patterns

Catherine mawia musyoka, anne mbwayo, dennis donovan, muthoni mathai.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2019 Oct 1; Accepted 2020 Aug 11; Collection date 2020.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Increase in alcohol and substance use among college students is a global public health concern. It is associated with the risk of alcohol and substance use disorders to the individual concerned and public health problems to their family and society. Among students there is also the risk of poor academic performance, taking longer to complete their studies or dropping out of university.

This study determined the prevalence and patterns of alcohol and substance use of students at the entry to the university.

A total of 406 (50.7% male) students were interviewed using the Assessment of Smoking and Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST) and the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Tool (AUDIT). Bivariate logistic regression analyses were used to examine associations between substance use and students' socio-demographic characteristics. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the predictors of the lifetime and current alcohol and substance use.

Lifetime and current alcohol and substance use prevalence were 103 (25%) and 83 (20%) respectively. Currently frequently used substances were alcohol 69 (22%), cannabis 33 (8%) and tobacco 28 (7%). Poly-substance use was reported by 48 (13%) respondents, the main combinations being cannabis, tobacco, and alcohol. Students living in private hostels were four times more likely to be current substance users compared with those living on campus (OR = 4.7, 95% CI: 2.0, 10.9).

A quarter of the study respondents consumed alcohol and/or substances at the entry to university pushing the case for early intervention strategies to delay initiation of alcohol and substance use and to reduce the associated harmful consequences.

Introduction

Alcohol and substance use has continued to rise globally, more so among college students [ 1 ]. Statistics show a consistency of alcohol and substance use across countries. Globally, a total population of about 275 million people used a psychoactive substance at least once in 2016 [ 1 ]. In the United States of America (USA) the rate of substance is rising among those aged 18 to 25 years, with many of them being new users [ 2 ]. Alcohol, cannabis, and opioids are the most used substances by those aged 18 to 25 years in America [ 3 ]. In this age group, the daily use of marijuana was reported by 2.6 million users, while 3.4 million (10%) had alcohol use disorders [ 2 ]. In Europe an estimated 19.1 million young adults (aged 15–34) used substances in 2018 [ 4 ]; males used substances twice as much as females with cannabis being the most used substance [ 4 ].

In Africa studies conducted in universities in Nigeria, Uganda, Ethiopia and South Africa have found that the prevalence of alcohol and substance use ranged between 27.5% and 62%[ 5 , 6 ]. The prevalence of substance use among undergraduate students in one university in Nigeria was reported at 27.5% [ 7 ]. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes (UNODC) 2018 report on substance use in Nigeria, puts the overall past-year prevalence at 14.3 million (14.4%) [ 1 ]. While use is reported across all age groups, the highest use was among the 25 to 39-year-olds and cannabis was the most used substance, with an average initiation age of 19 years; amphetamines and ecstasy use among young people was also reported [ 1 ]. Prescription opioids, mostly tramadol, morphine, and codeine, were also in high use; others included alcohol and tobacco use [ 8 ].

A higher prevalence of substance use, ranging from 20% to 68%, has also been found in different universities in Kenya [ 9 , 10 ].

A study at one Kenyan public university reported a substance use prevalence of 25.5%, with alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco being the most used substances [ 11 ].

Research shows that the transition periods from one life event to another are high potential entry points for youths to experiment with substance use and risky behaviours [ 12 ]. Students, aged between 18 to 25 years are at the transition point from high school education to college education [ 13 ]. This transition is associated with an increased risk for substance use initiation [ 14 ]. This risk in Kenya is exacerbated by the long waiting period students take to gain admission into the universities. During this waiting period, idleness may lead the youngsters to start experimenting with alcohol and substance use, behaviours which they may carry with them to the university. Furthermore, many of these students joining the university experience a new freedom from parental and teacher supervision. They additionally become responsible for larger sums of money than ever before in their lives [ 15 ]. The combination of these factors increases the susceptibility of the new students to harmful peer influence which may lead to alcohol and substance use initiation.

Age of onset of alcohol and substance use has dropped significantly worldwide from mean age 21 years in the mid-1980s to 10 years in 2012 [ 16 – 20 ]. The ages of 13 to 15 years are the critical years for the onset of substance use in Kenya [ 21 ]. Early initiation of substance use is positively predictive of the development of harmful immediate and long term consequences to the users [ 22 ]. Young people are particularly vulnerable to the harmful physiological effects of alcohol and substance use because of their immature body systems [ 20 , 23 ]. Psychologically, alcohol and substance use leads to disinhibition and a propensity for risky behaviours among young people [ 24 ]. This increases the risk of accidents and injuries, criminal behaviour, poor social relations, sexual assault, and risky sexual behaviour. In the long term, there is an increased risk of poor academic performance and the development of substance use disorders (SUD) [ 25 – 27 ].

Students who take alcohol and substances have been reported, more than their non-drug-using peers, to take longer to complete their studies, they get into trouble with university administration and some get expelled from the universities [ 28 ].

Universities, therefore, have to invest resources in the prevention and management of individuals with potential alcohol and substance use disorders to minimize the impact on their academic functioning and psychological wellbeing during their college years.

Programs for the prevention of alcohol and substances abuse are integral to many institutions of higher learning [ 29 ]. The strategies used include those aimed at universal prevention for those not yet using, selective prevention for those already experimenting with substances, and treatment of alcohol and substance use disorders for those suffering from harmful substance use [ 30 ]. The goal for universal prevention is to prevent young people from initiating substance use, while selective prevention is aimed at those at risk of problematic substance use [ 30 ]. In line with these practices, the University of Nairobi has a department on alcohol and substance abuse prevention that carries out activities to educate students on the negative effects of alcohol and substance use. There are also university counsellors who identify those students who abuse alcohol and substances and undertake counselling and rehabilitation [ 31 ]. Although the University has a policy of prohibiting alcohol or substance use in all its premises [ 31 ], students still get access to and use alcohol and other substances while at the university.

This study, therefore, aimed to determine the prevalence and patterns of alcohol and substance use of the students joining the University of Nairobi. The study findings will help guide universities to design and implement appropriate interventions for the prevention and management of alcohol and substance use among students.

Ethics and consent

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital and the University of Nairobi Ethical Committee (KNH-UoN ERC) P98/02/2018. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

This study was conducted at the University of Nairobi, which has 61,000 graduate and postgraduate students. Students are either publicly or privately sponsored. They may reside either in on or off-campus residences. The University of Nairobi has seven campuses located in Nairobi city and its environs ( www.uonbi.ac.ke ). The Chiromo and Kikuyu campuses were purposely selected as the study campuses. This choice was informed by previous surveys that have shown that students on these campuses have a high prevalence of substance use [ 32 ]. They were thus selected as the campuses that would provide the determination of the need for and design of prevention and intervention services. The selected campuses also have students who study varied courses in the sciences and humanities which were important to give a full representation of the study domains available in the university education system.

Study design and population

A cross-sectional study was done on first-year students of the academic year 2018/19 who joined the Kikuyu and Chiromo campuses of the University of Nairobi.

The students in the Chiromo campus take science-based programs like analytical chemistry, astronomy and astrophysics as well as environmental conservation and natural resources management.

Students in the Kikuyu campus take education-based courses like education science, physical education and education arts. These are all 4-year degree programs.

Sample size calculation

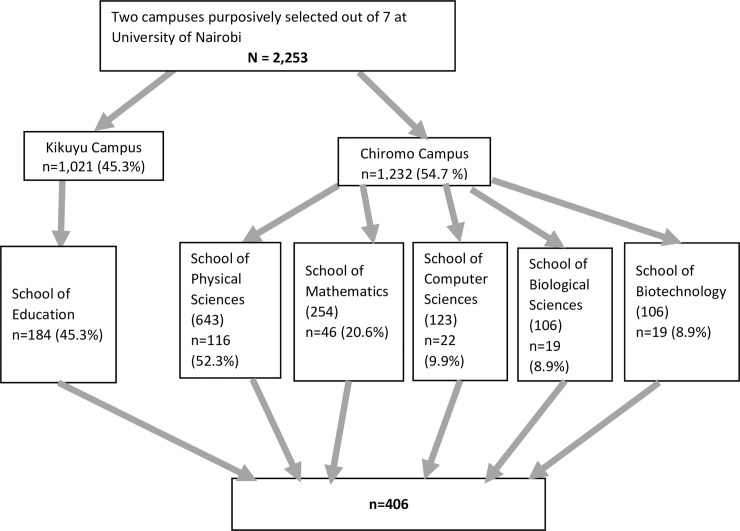

Using the Cochran’s formula for sample size calculation [ 33 ], a sample size of 406 respondents was obtained after adjusting for an anticipated 5% non-response rate. Given that Kikuyu campus had an enrolment of 1021 (45.3%) students and Chiromo campus had enrolled 1232 (54.7%) students, out of the sample size of 406, Chiromo proportionately contributed 222 (54.7%) and Kikuyu campus contributed 184 (45.3%).

Sampling procedure

Sampling probability to population size (PPS) strategy was employed. At the first stage, purposive sampling of the seven campuses of the University of Nairobi selected Kikuyu and Chiromo campuses. This selection was based on the documented high prevalence rates of alcohol and substance abuse among the students of these campuses [ 32 ].

At the second stage, total population sampling was done whereby all the six schools making up the Kikuyu and Chiromo campuses were studied. These schools are Education in Kikuyu, and Physical Sciences, Biological Sciences, Mathematics, Biotechnology and Computing in Chiromo.

At the third stage, the enrolment lists of first-year students in these schools were obtained and used to make the sampling frame for simple random sampling. The frame comprised 1,021 (45.3%) students in Kikuyu and 1,232 (54.7%) students in Chiromo. Kikuyu Campus with its one school retained the size of its frame for its School of Education. In Chiromo Campus the five schools had each allocated a population-proportionate sampling weight ( Fig 1 ). These various sampling frames were used for the third stage of sampling.

Fig 1. Flow chart of the sampling procedure.

Simple random sampling was applied to each of the constructed sampling frames. First, students were assigned a number starting from 1–1,021 in Kikuyu Campus and 1–1,232 in Chiromo Campus.

Random numbers were generated from the computer software Random.org and used to select study participants from each school. Secondly, the students in each school of Chiromo campus were randomly sampled by application of proportions to the population as summarized in Fig 1 . A final total of 406 study participants was selected.

Data collection

Data were collected between September and November 2018 using the World Health Organization (WHO) Assessment of Smoking and Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST) [ 34 ], the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Tool (AUDIT) [ 35 ] and a researcher designed socio-demographic questionnaire.

Data collection tools

A researcher designed socio-demographic questionnaire was used to collect data on sex, date of birth, age, school of study, course of study, sponsorship (public or private), marital status and residence while studying. The ASSIST tool identifies more than 10 different types of substances including alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco, which are the most commonly used drugs by students [ 34 , 36 ]. Participants were asked if they had ever (lifetime) used alcohol and/or any of the listed substances and if the answer was affirmative, more detailed information was obtained about the previous 3-month frequency and consequences of use of the endorsed substances. The AUDIT-10 tool includes 10 questions that assess alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems. Response options range from 0 to 4 and a summed total range from 0 to 40 scores. A score of 8 or more indicates hazardous or harmful or probable dependent drinking [ 37 ].

The consumption-related items assess binge drinking, defined by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) as the use of four or more standard drinks for women and seven or more standard drinks for men on any one occasion and at least once a week [ 38 ]. These tools have been validated for use in various settings involving a wide range of populations [ 36 ]. The validity and reliability of the ASSIST and AUDIT tools have been reported as good; they have been adapted for use in Kenya to investigate substance use among university students [ 10 , 39 ].

Questionnaire administration and retrieval

The questionnaires were administered in classrooms, 30 minutes before a lecture, with permission from the lecturer and assistance of the class representatives. All the students enrolled in a particular school were assigned a unique student number. These numbers were used to make a list. The randomization program ( Random.org ) was used to generate a list of those numbers to be selected. The students whose numbers were selected were then approached and requested consent to participate in the survey. If the student was not present in class on the day of data collection or if they declined to participate, the student whose number was next on the list was approached and requested to participate. This process was repeated until the required sample size of 406 was achieved. Filled questionnaires were collected by the principal investigator (PI) or research assistants and immediately checked for completeness. They were then transported and securely stored in a locked drawer, which accessible only to the PI to be retrieved later for further cleaning and data processing.

Variable measures

The main outcomes of alcohol and substance use were assessed as ‘Ever Used’ and ‘Current Use’. Following guidelines for the ASSIST, ‘current use’ was defined by consumption or use of alcohol or other substances in the immediate 3 months preceding the day of data collection. Patterns of alcohol use among the students were measured by the AUDIT-10.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were coded and entered using the EpiData 3.1 software. It was checked for inconsistencies and missing values. Incomplete questionnaires were dropped at this point. The cleaned data were exported to Stata software. Data were stratified by study campus and school. The sampling scheme was self-weighing. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software version 14.2 Special Edition. Stata survey suite was used to adjust for the stratification on data analysis.

Related questions were aggregated to indicate the prevalence of any alcohol or substance used in a lifetime and current use which was defined as use within the immediate 3 months before the day of data collection. Summaries of the lifetime and current use prevalence and social demographic variables were done using descriptive statistics such as mean and mode. Associations between the outcome variables for the lifetime and current use and the independent variables were examined by calculating odds ratios. The variables that were statistically significant at the p < 0.05 levels in bivariate analyses were used to create multivariate models. Multivariate logistical regression was used to assess the impact of explanatory variables on the outcome of the lifetime and current substance use prevalence, for women and men separately.

Baseline characteristics of the study respondents

A total of 406 study respondents consented to participate in the study. Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. Just over half (222/406, 54.7%) the respondents were registered for courses in Chiromo campus. By sex, approximately half of the respondents 206/406 (50.7%) were male.

Table 1. Social demographic characteristics of the study respondents.

The mean age of all respondents was 19.3± 1.2 years. The majority (371/406 (93.7%), were public sponsored and 318/406 (78.5%) resided on campus at university hostels.

Prevalence of substance use among the study respondents

The prevalence rates of substance use among the study respondents are as presented in ( Table 2 ). Overall 103 respondents (25.4%, 95% CI:21.21, 29.90) had ever used alcohol or another substance in their lifetime. Alcohol was the most used substance, having been ever used by 89/406, (21.9%, 95% CI:17.99, 26.27) of the study respondents in their lifetime. Cannabis was ever consumed by 33/406 (8.1%, 95% CI: 5.66, 11.23) of the study respondents. All the other groups of drugs listed (opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens, sedatives, and inhalants) had been used by (9.4%, 95% CI: 6.71, 12.62) of the respondents. Males had a higher prevalence of lifetime substance use at 63/206 (30.6%, 95% CI: 24.37, 37.36) compared to females at 40/200 (19%, 95% CI:13.81,25.13). This pattern was replicated across most substances assessed.

Table 2. Prevalence and associated confidence intervals by sex among the study respondents.

*opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens, sedatives, and inhalants.

The overall prevalence of recent substance use (reported use in the last three months) was 83/406 (20.4%, 95% CI: 16.62, 24.70). A similar pattern to that of ever use of substances was reported, with males’ current use of alcohol (22.8%,95% CI:17.27,29.16) being double the females’ rates of use for alcohol (11.00% 95% CI: 7.02, 16.18), this higher pattern of substance use among the males was replicated across most of the other substances ( Table 2 ).

Patterns of current substance use (use within last 3 months before the study)

The study participants who reported current alcohol use 42/406 (10.3%) drank twice or more times per month, 15/406 (3.7%) drank at least once a month while 8/406 (2%) drank alcohol every week and 4/406 (1%) drank daily ( Table 3 ). Weekly use of cannabis was reported by 6/406 (1.5%) of the users, while 13/406 (3.2%) used cannabis twice or more times per month. Out of the six respondents who reported use of cocaine two reported daily use, while the others used at least once a month ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Patterns of substance use among study respondents within the last 3 months.

Predictors of current and lifetime substance use among study respondents.

Female first-year students had a significantly lower odds of current substance use compared to their male counterparts, (Odd Ratio (OR) 0.43(0.19–0.95), p<0.005) ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Predictors of the lifetime and current substance use among study respondents adjusting for sampling weights.

*Significant at p≤0.05.

There was no significant difference in odds of current substance use between students who were government-sponsored compared to the privately sponsored ones. However, students who lived in private hostels were four times more likely to be current substance users as compared to those who resided in campus hostels (OR 4.40(1.14–16.86), p<0.005) ( Table 4 ).

The odds of current substance use by respondents from the School of Biological Sciences were five times those of the respondents from the School of Physical sciences (OR 5.10 (1.60–16.38), p<0.05) ( Table 4 ).

This study examined the prevalence, patterns, and predictors of the lifetime and current alcohol and substance use among first-year students at the University of Nairobi.

The overall lifetime substance use prevalence was found to be 25.4%. This is a considerably high rate, with nearly a quarter of the respondents using alcohol and other substances at admission to the university. The findings of this study are comparable with those of a similar study among students of Kenyatta University which found a lifetime substance use prevalence of 25.1% [ 11 ]. The comparability of findings may be due to students of the two universities being drawn from similar catchment populations as well as staying in the same urban settings.

The study findings are however, lower than those found in a study done among college students in Eldoret, Kenya, which found a lifetime substance use prevalence of 69.7% [ 9 ]. Given that the Eldoret study and the present one had respondents of similar age and education, differences in geographical locations and settings between Eldoret and Nairobi may explain the disparities of findings. Eldoret is located in a more rural setting as compared to the very metropolitan Nairobi, the capital city of Kenya. It is expected that students in the major cities have more vulnerabilities as well as opportunities for alcohol and substance use. Nevertheless, students in a major city may be more exposed to information on the negative effects of substance use due to connection to the internet and programs that target the prevention of substance use among university students. Moreover, the study done in Eldoret was done eight years earlier; a lot has changed in Kenya in terms of legislation concerning alcohol and substance use, and implementation of the Alcoholic Drinks Control Act 2010, revised 2012 [ 40 ].

The national prevalence of lifetime substance use in Kenya, for those aged 15–24 years, is 37.1% while the current substance use is 19.8% [ 19 ], these figures are higher than the lifetime substance use prevalence of 25.4% and 17% current substance use found by this study. However, this study found a higher prevalence of current alcohol and cannabis use at 17% and 5.2% compared to the Kenyan national prevalence of 11.7% and 1.5% respectively [ 19 ]. These higher trends of the current use of alcohol and cannabis by university students may be explained by the normalizing of substance use behaviour and aggressive marketing of alcohol and other substances among college students through digital platforms and social media like Facebook and WhatsApp, of which college students are prolific users [ 41 ].

The prevalence of substance use in studies across different geographical locations and social-economic environments in Africa showed comparable results to those reported by our study. In Northern Tanzania, a study by Francis et al reported a prevalence of current alcohol use of 45% among male college students and 26% among female students [ 42 ]. In South Africa, Ramsoomar et el , in a study done among adolescents at 13 and 18 years, found that the prevalence of lifetime use of substances rose from 22% at 13 years to 66% at 18 years [ 18 ]. A study among medical students in Nigeria reported a lifetime prevalence of use of mild stimulants of 46.1%, alcohol, 39.7%, and tobacco, 6% [ 43 ]. The prevalence of stimulant use in the Nigerian study was higher than the prevalence reported in our study. Besides, the use of alcohol is more common among our study respondents as compared to the use of stimulants. However, the prevalence rates of tobacco and cannabis were comparable to the findings in our study. This may be explained by the fact that all the study sites are in urban settings and the risks and exposures to substance use are comparable in most of the cities.

Prevalence studies done in European countries showed some similarities as well as contrasting findings. In France, a study among university students reported the prevalence of alcohol and tobacco consumption was at 20.1% and 23.2% respectively [ 44 ]. Studies among university students in nine member countries of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) found varying prevalence rates of illicit drugs, ranging from 0.2% in Cambodia to 45.7% in Laos [ 26 ]. The prevalence rates of our study fall within these ranges.

In the study among French students, even though the prevalence of alcohol use was comparable to the findings of our study, the reported 23.2% prevalence of tobacco consumption was higher than the 5.1% current use reported by our study. This difference in tobacco use among French study respondents and the respondents in our study may be accounted for by the tobacco control measures by the government of Kenya through the enacted Tobacco control act 2007 revised (2012), which has prohibited tobacco use in all public places among other controls [ 45 ]. These differences also support the premise that government legislation and enforcement are important in controlling substance use among young people.

The results for the prevalence of lifetime substance use by age showed a slightly higher rate among students who were 20 years and above compared to those aged below 19 years. There was, however, little difference in the prevalence of current substance use among students in the two age categories. Studies have shown that substance use behaviour is highest at the age of 18 to 24 years [ 46 ]. Young people at this age pursue their university education; at the same time, the age of initiation to alcohol and substance use has reportedly reduced in recent years [ 20 ]. In Kenyan studies, university students are among the leading categories of substance users [ 10 ].

There was a sex difference in the use of substances; males had higher rates of use in all categories of substances. These results are similar to those from other parts of the world in which males college students have been found to have higher rates of substance use than females students [ 5 , 42 , 47 ]. This trend may be a result of societies that are more tolerant of substance use among men as opposed to women.

The residence of the university students was associated with differences in the rates of substance use. The study results indicated that 48% of the students who reported current alcohol and substances use resided in private hostels.

Those who resided at home with parents were the second-largest users, while those who resided in university hostels reported the least substance use. These findings contradict an earlier study by Simons-Morton et . al , which found that students who resided in campus residences had the highest substance use [ 48 ]. The findings, however, are in agreement with a study that found that living in off-campus residences posed a high risk of alcohol use [ 49 ]. Private student hostels in Kenya do not have strict enforcement of rules regarding the use of alcohol and drugs in their premises. The landlords would not want to lose tenants by enforcing restriction measures on substance use by the student residents. This therefore, accords the resident students liberties to behave as they please, thus making them more vulnerable to substance use. This phenomenon could also be as a result of the difference in the social-economic status of students who reside in on or off-campus accommodation. In Kenya, students who reside in off-campus residences are often from a higher social economic background as compared to those using on-campus accommodation facilities. This underpins the need to have prevention interventions among university students target both on-campus and off-campus residents. Most of the preventive interventions for alcohol and substance use among university students focus on-campus facilities, this leaves out a vulnerable group in off-campus student residents.

The patterns of alcohol use found in the study also reveal that most students only used alcohol occasionally. This was most likely during the weekends when they socialize with their friends. This is of concern because these students often may take many substances at one sitting, as well as mixing different types of substances. Research evidence shows that students who binge drink are most likely to suffer acute and negative consequences of substance use [ 46 ]. There were 5% of students who reported regular use of alcohol, some even daily use. These students are of concern given that they are at great risk of having their substance use alter the cognitive and physical functioning. This potentially would lead to poor academic outcomes as well as violence and criminal activities as has been documented in previous studies [ 23 , 50 ].

Given the high number of students who used alcohol and other substances by the time they reported for university education, preventive interventions should start at the pre-university level. These levels include at high schools and home environments and they should be intensified throughout their university education period.

Current models of delivering alcohol and substance use prevention interventions include face-to-face interventions with the college students however, these are difficult to implement, because of the stigma associated with substance use. As a result, only 10–15% of college students receive the interventions needed to address their substance use problems [ 51 ]. Innovative and youth-friendly intervention strategies are key to prevent alcohol and substance use among university students [ 30 ]. The use of technology-based interventions would provide a more acceptable avenue to deliver evidence-based interventions to college students compared to face-to-face programs [ 30 ]. University management should explore all avenues to provide innovative strategies for the prevention of alcohol and substance use, as well as related negative consequences, among their students.

Strengths of the study

This study provides epidemiological information about the prevalence and patterns of alcohol and substance use among first-year university students. Furthermore, the results of this study have positive implications for strengthening interventions on substance use prevention among university students as well as a reference point for future comparative studies.

Limitations of the study

This study used a cross-sectional design and data; as such, this precluded any causal associations to be made on the factors associated with alcohol and substance use.

Also, the self-report measures employed in data collection may have led to recall and reporting bias as students may have given socially desirable responses, thus potentially leading to over/under-reporting of the prevalence of substance use.

To minimise on recall bias, we used pictorial charts of standard alcoholic drinks to aid the respondents. Moreover, we emphasized to the respondents the need to be truthful as their responses were confidential. This study was done on two campuses of a single public university; thus the findings may not be generalizable to other universities.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study demonstrated that the prevalence of alcohol and substance use among first-year university students at the Kikuyu and Chiromo campuses of the University of Nairobi is high. Interventions for the prevention and management of alcohol and substance use should therefore, start as early as at the entry to university. Thematic orientation programs are key to educate first-year university students on the negative effects of alcohol and substance use. Life skills training should be instituted to help students adjust and adapt to their university life well. Off-campus residence, advanced age, and male gender of university students were found to be positively predictive of their use of alcohol and other substances. Therefore, alcohol and substance use prevention intervention strategies should allow extra focus on these vulnerable sub-groups. Universities should also increase the available accommodation facilities for their students since living in on-campus residences was found to be associated with lower rates of substance use. This would also make prevention interventions among college students easier to implement.

We propose that programs for alcohol and substance use prevention and education should have a multi-sectoral approach, which should start at high school level and be intensified as the young adults join university education.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments.

We are grateful to the study participants for their genuine participation in this research and the research assistants for their commitment to this study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

CMM received the research award "This research was supported by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA). CARTA is jointly led by the African Population and Health Research Center and the University of the Witwatersrand and funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Grant No--B 8606.R02), Sida (Grant No:54100113), the DELTAS Africa Initiative (Grant No: 107768/Z/15/Z) and Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD). The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust (UK) and the UK government. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Fellow". www.aphrc.org www.cartafrica.org The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

- 1. World Drug Report U. World Drug Report, Youth. 30 Sep 201. New York, United States: United Nations; 2018. 1–62 p.

- 2. McCance-Katz EF. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). SAMHSA—Subst Abus Ment Heal Serv Adm. 2017;53. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Organization of American States C. Report on Drug Use in the America 2019. Washington, D.C., 2019.: Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD), Organization of American States (OAS), Report on Drug Use in the Americas 2019, 2019.

- 4. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs. European Drug Report [Internet]. European Union Publications Office. 2019. 1–94 p. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/4541/TDAT17001ENN.pdf_en

- 5. Kassa A, Taddesse F, Yilma A. Prevalence and factors determining psychoactive substance (PAS) use among Hawassa University (HU) undergraduate students, Hawassa Ethiopia. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2014;14:1044 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4288666&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1044 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Nwanna UK, Sulayman AA, Oluwole I, Kolawole AK, Komuhang G, Lawoko S. Prevalence & Risk Factors for Substance Abuse among University Students in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Med Res Public Heal (IJMRPH. 2018;1(2):1–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Johnson OE, Akpanekpo EI, Okonna EM, Adeboye SE, Udoh AJ. The prevalence and factors affecting psychoactive substance use among undergraduate students in University of Uyo, Nigeria. J Community Med Prim Heal Care. 2017;29(2):11–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Drug Use in Nigeria. 2018;61. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Atwoli L, Mungla P a, Ndung’u MN, Kinoti KC, Ogot EM. Prevalence of substance use among college students in Eldoret, western Kenya. [Internet]. Vol. 11, BMC psychiatry. 2011. p. 34 Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/11/34 10.1186/1471-244X-11-34 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Ndegwa S, Munene A, Oladipo R. Factors Associated with Alcohol Use among University Students in a Kenyan University. 2017;1:102–17. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Tumuti S, Wang T, Waweru EW, Ronoh AK. Prevalence, Drugs Used, Sources, And Awareness of Curative and Preventive Measures among Kenyatta University Students, Nairobi County, Kenya. J Emerg Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 2014;5(3):352–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Monitoring the Future. Drug Monitoring the Future 2017. Teen Drug Use. 2017;2017.

- 13. Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. Behavioral Risks During the Transition From High School to College. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(5):1497–504. 10.1037/a0012614 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. White HR. To Adulthood: A Comparison of College Students. 2005;281–305. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Ayalew M, Tafere M, Asmare Y. Prevalence, Trends, and Consequences of Substance Use Among University Students: Implication for Intervention. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2018;38(3):169–73. 10.1177/0272684X17749570 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Peltzer K, Phaswana-mafuya N, Africa S, Chancellor DV. Drug use among youth and adults in a population-based survey in South Africa. 2012;1–6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the FUTURE: College Students & Adults Ages 19–55. Monitoring the Future. 2014;2. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Ramsoomar L, Morojele NK, Norris SA. Alcohol use in early and late adolescence among the Birth to Twenty cohort in Soweto, South Africa. 2013;19274(5):57–66. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Nacada. Rapid Situation Assessment of the Status of Drug and Substance Abuse. 2012.

- 20. Nair UR, Vidhukumar K, Prabhakaran A. Age at Onset of Alcohol Use and Alcohol Use Disorder: Time-trend Study in Patients Seeking De-addiction Services in Kerala. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38(4):315–9. 10.4103/0253-7176.185958 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. NACADA (National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse). National Survey on Alcohol and Drug Abuse Among Secondary School. 2016;1–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. WHO. Global Health Risks. 2009.

- 23. White A, Hingson R. the Burden of Alcohol Use College Students. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2013;35(2):201–18. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Donovan E, Das Mahapatra P, Green TC, Chiauzzi E, McHugh K, Hemm A. Efficacy of an online intervention to reduce alcohol-related risks among community college students. Addict Res Theory. 2015;23(5):437–47. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Zufferey A, Michaud PA, Jeannin A, Berchtold A, Chossis I, van Melle G, et al. Cumulative risk factors for adolescent alcohol misuse and its perceived consequences among 16 to 20-year-old adolescents in Switzerland. Prev Med (Baltim). 2007;45:233–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Yi S, Peltzer K, Pengpid S, Susilowati IH. Prevalence and associated factors of illicit drug use among university students in the association of southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Subst Abus Treat Prev Policy. 2017;12(1):1–7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. UNODC WDR. World Drug Report 2019. 2019.

- 28. Skidmore CR, Kaufman EA, Crowell SE. Substance Use Among College Students. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;25(4):735–53. 10.1016/j.chc.2016.06.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Sundström C, Gajecki M, Johansson M, Blankers M, Sinadinovic K, Stenlund-Gens E, et al. Guided and unguided internet-based treatment for problematic alcohol use—A randomized controlled pilot trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(7). [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Marsch LA, Borodovsky JT. Technology-based Interventions for Preventing and Treating Substance Use Among Youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;25(4):755–68. 10.1016/j.chc.2016.06.005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. University of Nairobi. UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI PREVENTION OF ALCOHOL AND DRUGS ABUSE POLICY. 2015;2011(FEBRUARY 2011).

- 32. Hassan MN. Factors Associated With Alcohol Abuse among University of Nairobi Students. Biomedcnetral psychiatry. 2013;7(5):69–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Daniel WW 1999. BIOSTATISTICS. Vol. 53, Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 1999. 1689–1699 p. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. WHO. WHO | The ASSIST project—Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test. World Health Organization; 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. WHO. World Health Organization; 2001. 3–4 p. [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Humeniuk R, Ali R. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and Pilot Brief Intervention: A Technical Report of Phase II Findings of the WHO ASSIST Project. 2006;[inclusive pages].

- 37. SAUNDERS JB, AASLAND OG, BABOR TF, DE LA FUENTE JR, GRANT M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption‐II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. DeMartini KS, Fucito LM, O’Malley SS. Novel Approaches to Individual Alcohol Interventions for Heavy Drinking College Students and Young Adults. Curr Addict Reports [Internet]. 2015;2(1):47–57. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40429-015-0043-1 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Muriungi SK, Psychology C, Ndetei DM, Chb MB, Psych MRC, Psych FRC. Effectiveness of psycho-education on depression, hopelessness, suicidality, anxiety and substance use among basic diploma students at Kenya Medical Training College. 2013;19(2). [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Alcoholic drinks control act. 2012;(4).

- 41. Anderson P, De Bruijn A, Angus K, Gordon R, Hastings G. Special issue: The message and the media: Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(3):229–43. 10.1093/alcalc/agn115 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Francis JM, Weiss HA, Mshana G, Baisley K, Grosskurth H, Kapiga SH. The epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders among young people in Northern Tanzania. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):1–17. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Makanjuola A., Abiodun O., Sajo S. Alcohol and psychoactive substance use among medical students of the University of Ilorin, Nigeria. Eur Sci J. 2014;10(8):69–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Tavolacci MP, Ladner J, Grigioni S, Richard L, Villet H, Dechelotte P. Prevalence and association of perceived stress, substance use and behavioral addictions: a cross-sectional study among university students in France, 2009–2011. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2013;13(1):724 Available from: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-724 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Tobacco control act. 2012;(4).

- 46. Dhanookdhary AM, Gomez AM, Khan R, Lall A, Murray D, Prabhu D, et al. Substance Use among University Students at the St Augustine Campus of The University of the West Indies. 2010;59(6). [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Silva LVER, Malbergier A, Stempliuk V de A, de Andrade AG. [Factors associated with drug and alcohol use among university students]. Rev Saude Publica [Internet]. 2006;40(2):280–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16583039 10.1590/s0034-89102006000200014 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Simons-Morton E T. Social Influence on the Prevalence of Alcohol Use Among. 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Benz MB, DiBello AM, Balestrieri SG, Miller MB, Merrill JE, Lowery AD, et al. Off-Campus Residence as a Risk Factor for Heavy Drinking Among College Students. Subst Use Misuse [Internet]. 2017;52(9):1133–8. Available from: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1298620 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Tahtamouni LH, Mustafa NH, Alfaouri AA, Hassan IM, Abdalla MY, Yasin SR. Prevalence and risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse among Jordanian collegiate students and athletes. Eur J Public Health [Internet]. 2008;18:661–5. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-56749177301&doi=10.1093%2Feurpub%2Fckn062&partnerID=40&md5=28ac60872878d619c58fa494d57470c1 10.1093/eurpub/ckn062 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Cagande CC, Pradhan BK, Pumariega AJ. Treatment of adolescent substance use disorders. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2014;25(1):157–71. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data availability statement.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (715.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Open access

- Published: 29 March 2021

Interventions for adolescent alcohol consumption in Africa: protocol for a scoping review including an overview of reviews

- Alice M. Biggane 1 ,

- Eleanor Briegal 1 &

- Angela Obasi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6801-8889 1 , 2

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 88 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2063 Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Harmful alcohol use is a leading risk to the health of populations worldwide. Within Africa, where most consumers are adolescents, alcohol use represents a key public health challenge. Interventions to prevent or substantially delay alcohol uptake and decrease alcohol consumption in adolescence could significantly decrease morbidity and mortality, through both immediate effects and future improved adult outcomes. In Africa, these interventions are urgently needed; however, key data necessary to develop them are lacking as most evidence to date relates to high-income countries. The purpose of this review is to examine and map the range of interventions in use and create an evidence base for future research in this area.

In the first instance, we will conduct a review of systematic reviews relevant to global adolescent alcohol interventions. We will search the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL, Web of Science, Global Health and PubMed using a broad search. In the second instance we will conduct a scoping review by drawing on the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley. We will search for all study designs and grey literature using the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL, Web of Science and Global Health, Google searches and searches in websites of relevant professional bodies and charities. An iterative approach to charting, collating, summarising and reporting the data will be taken, with the development of charting forms and the final presentation of results led by the extracted data. In both instances, the inclusion and exclusion criteria have been pre-defined, and two reviewers will independently screen abstracts and full text to determine eligibility of articles.

It is anticipated that our findings will map intervention strategies aiming to reduce adolescent alcohol consumption in Africa. These findings are likely to be useful in informing future research, policy and public health strategies. Findings will be disseminated widely through peer-reviewed publication and in various media, for example, conferences, congresses or symposia.

Protocol Registration

This protocol was submitted to the Open Science Framework on May 03, 2021. www.osf.io/qnvba

Peer Review reports

Harmful alcohol use is a leading risk to the health of populations worldwide; it is a significant barrier to achieving many health-related targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including those for maternal and child health, infectious diseases, noncommunicable diseases, mental health and injuries and poisonings [ 1 ]. Alcohol use represents a key public health challenge in Africa where it accounts for more deaths and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost than in any other region [ 1 , 2 ] and twice as many preventable deaths as tobacco [ 3 ].

Most alcohol consumers in Africa are adolescents and young people; the use is highly gendered, and adolescent males are at particular risk [ 4 ]. Evidence suggests that early alcohol initiation (aged < 14 years) predicts alcoholism in middle age [ 1 ] and is potentially a more powerful precursor to alcoholism than excess drinking in early adulthood [ 1 ]. Adolescents are more vulnerable to alcohol-related harm per volume than adults [ 1 ], and those who drink are more likely than their elders to engage in heavy episodic drinking (HED) (> 60 g alcohol at least once in the preceding month), which the WHO (World Health Organization) has identified as the most deleterious drinking pattern [ 5 ]. Alcohol use in adolescents is associated with alterations in verbal learning, visual–spatial processing, memory and attention as well as with deficits in development and integrity of the grey and white matter of the central nervous system [ 6 ]. These neurocognitive alterations are associated with behavioural, emotional, social and academic problems in later life [ 7 , 8 ]. Further, alcohol consumption in adolescence is associated with sexual risk taking [ 9 ], adverse HIV outcomes, self-harm, suicide and the perpetration of sexual violence [ 4 ].

Interventions to prevent or substantially delay alcohol uptake and decrease alcohol consumption in adolescence could significantly decrease morbidity and mortality, through both immediate effects and future improved adult outcomes [ 4 , 10 ]. These interventions are urgently needed in Africa; however, key data necessary to develop them are lacking as most evidence to date relates to high-income countries (HICs) [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. We are aware of only one systematic review which included an evaluation of interventions to reduce adolescent alcohol consumption [ 14 ]; it featured one study from Africa [ 15 ]. This evidence gap was highlighted by Das et al. in their 2016 global overview of systematic reviews regarding adolescent substance abuse interventions including alcohol, in which they cautioned “there is a dire need for rigorous, higher quality evidence especially from low- and middle-income countries” [ 16 ]. This call has since been echoed by others [ 17 ]. The current review complements this work and specifically aims to map and characterise the specific adolescent alcohol interventions which have been used in Africa.

Types of intervention

Adolescent alcohol use is shaped by a complex range of factors acting at multiple levels in the environments in which adolescents grow and develop [ 18 ]. These levels of influence are commonly categorized in socio-ecological frameworks [ 18 , 19 ] as macro-system (e.g. policies, societal beliefs and cultures), community level (neighbourhood risks and resources), micro-system (households, schools, peer networks), and individual level (gender, age, socioeconomic status).

Figure 1 illustrates how interventions seek to exert effects or modify factors at one or more of these levels and how strategies used to deliver the interventions within settings (e.g. teachers and/or peers as educators in school-based programmes) vary. Theoretical models underpinning proposed mechanisms of action for intervention (e.g. Stages of Change model vs. Theory of Planned Behaviour) also vary. We will assess the available evidence for each type of intervention and identify evidence gaps to inform future research and implementation.

Intervention levels and example mechanisms of action

This review protocol has been registered within the Open Science Framework database (registration number: www. osf.io/qnvba ). Further, this review protocol is also being reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement as appropriate which can be found in Additional File 1 [ 20 , 21 ].

The review will be conducted in two stages. First, in stage one, the proposed overview of systematic reviews will capture systematic reviews published since 2000 to complement Das et al.’s 2016 overview of systematic reviews [ 16 ] and provide the most up to date syntheses of the evidence base. This overview of reviews will be reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 [ 20 , 21 ].

Second, in stage two, the proposed scoping review of peer reviewed and grey literature published since 2000 will identify interventions and gaps in the evidence base relating to adolescent alcohol interventions in Africa. This will be reported in accordance with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) [ 22 ].

The methodologies for each of the above two stages are described in what follows. In both stages, interventions will be categorized by setting, delivery model and theoretical construct. Adolescents are defined as those aged 10–19 years; however, since many studies target youth (aged 15–24 years), we will include reviews and interventions targeting older groups if adolescents are also included. If possible, we will stratify our findings by age. Otherwise, we will report the combined results for adolescents and youth as representative of the population of interest. If we identify a new, relevant systematic review providing good quality evidence for appropriate interventions in Africa, we will at that point discuss the need for the scoping review and proceed as deemed appropriate.

Stage 1: Overview of systematic reviews

We will identify and review recent Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews of randomised or non-randomised controlled trials, which fully or partly addressed alcohol interventions for adolescents. For the purpose of this review, we have defined a systematic review as a review of evidence based on a clearly formulated question, to identify and critically appraise relevant research by following a systematic, explicit and repeatable methodology [ 23 ].

Eligibility criteria

We will develop a comprehensive search strategy to review the available literature underpinned by our pre-defined inclusion criteria (Table 1 ).

Our pre-defined exclusion criteria are as follows:

No information on an alcohol use intervention

Duplicate publications

Reviews other than systematic, e.g. narrative, scoping

Grey literature

Published before 2000

Interventions that were not purposely developed to target adolescent alcohol consumption

Interventions that were exclusively targeting individuals aged 25 years or more

Identifying relevant studies

We will search the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL, Web of Science, Global Health and PubMed for publications published from January 2000 onwards, using a broad search strategy building on that outlined by Das et al. [ 16 ] in their 2016 overview. This will include a combination of appropriate keywords, medical subject headings (MeSH terms) and free text terms; an outline of our search strategy for PubMed is available in Additional File 2 ; it will be updated accordingly for the other databases. We will also examine cross-references and bibliographies of included publications to identify additional sources of information. If required, we will contact the publication’s lead author to clarify or seek additional information. All articles identified from the literature search will be screened by two reviewers independently. First, titles and abstracts of articles returned from the initial searches will be screened based on the eligibility criteria outlined above. Second, full texts will be examined in detail and screened for eligibility. Third, references of all considered articles will be hand-searched to identify any relevant publication missed in the search strategy. Any disagreements on selection of reviews will be resolved via discussion and if needed the input of a third reviewer. A flow chart showing studies included and excluded at each stage of the screening process will be included in the full publication [ 24 ].

Extracting and charting the data

After retrieval of the full texts of all the reviews that meet the inclusion criteria (Table 1 ), data from each review will be extracted, independently by two reviewers, in a standardised form using Microsoft Excel. Data we will collect includes but is not limited to:

Author(s), year of publication, publication type, study location

Study populations—characteristics and locations

Aims of study

Intervention details building on the TIDieR Format [ 25 ] (name, rationale/theory, materials, provider, mode, context (e.g. school/community/clinic), intensity and duration, tailoring, modification, fidelity)

Comparator (if any)

Target demographics (gender, age, i.e. older/younger adolescents (10–14/15–19))

Geographical location—country

Setting (e.g. urban/rural)

Outcome measured

Measurement of treatment effects

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Risk of bias tool

As shown in Fig. 1 , the types of intervention will vary, and we anticipate that some may be complex interventions operating at more than one ecological level. For example, community-based interventions aimed at decreasing alcohol availability for adolescents may be combined with school-based programmes targeting individual knowledge. The latter maybe delivered by teachers or peer educators.

These elements and any other relevant information regarding the intervention programmes (socio-ecological level, setting, delivery mechanism, target group, behaviour change theory), acceptability and costs will be extracted. When there is missing data, we will attempt to contact the original authors to obtain the relevant information. We do not have any pre-planned data assumption or simplifications. We will extract pooled effect size for the outcomes reported by the review authors with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We will assess and report, in duplicate, the quality of included reviews using the 11-point assessment of the methodological quality of systematic reviews (AMSTAR-2) criteria [ 26 ]. We will report the final results using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting tool [ 24 ].

Data analysis

We will analyse the data arising from all included publications to create an overview of the various adolescent alcohol interventions being used global and their reported effectiveness and location. We plan to analyse the data using descriptive statistics via Microsoft Excel and report the findings narratively, using tables to characterise key features, interventions and findings. We will also seek to identify whether interventions were exclusively designed to target alcohol consumption or were part of a wider substance abuse or healthcare intervention. Where possible, we will explore both the variations and overlap that may exist in findings of the reviews, as well as issues such as the numbers of studies included, date ranges covered by the reviews, sample sizes, target populations and settings. However, we will be adaptive to the data we extract and the subsequent analysis as appropriate.

- Scoping review

A scoping review will allow us to identify and map the range and type of interventions as described in Fig. 1 [ 24 , 27 ]. A strength of this type of review is that, in addition to published articles, we will also search for grey literature, such as reports and guidance documents as it is possible that some of the information being sought (i.e. descriptions of alcohol interventions in use) for our target population are documented in non-traditional forms of scientific publications. In designing our scoping review protocol, we draw on Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework [ 27 ] and its amendments [ 28 , 29 ] as follows.

Identifying the research question

Based on gaps in the literature and the study team’s knowledge of the field these are as follows:

What interventions have been used to delay, reduce or otherwise modify alcohol consumption among adolescents in Africa?

What are the settings, delivery methods, theoretical bases and reported effectiveness of these interventions?

These questions will be refined, or new ones added, as the researcher team becomes familiar with the literature [ 27 ].

We will develop a comprehensive search strategy to review the available literature using the ‘Population–Concept–Context (PCC)’ framework for scoping reviews [ 30 ], underpinned by our pre-defined inclusion criteria (Table 2 ).

Protocol only

Not used in Africa

Drawing on the three-step process recommended by JBI [ 29 ], we will systematically search the following databases: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL, Web of Science and Global Health for relevant publications from the year 2000 onwards. We will also perform targeted searches for grey literature published from the year 2000 onwards, by searching (1) Google, (2) relevant discipline-based listservs (e.g. academic institutes) and (3) the websites of agencies that fund or implement public health interventions in Africa (e.g. ministries of health, charity organisations). Relevant blogs, newsletters, reports and surveys will also be considered.

The draft literature search for MEDLINE (Ovid) can be found in supplementary information Additional File 3 , which uses a combination of keywords, MeSH and free text terms; it will be updated accordingly for the other databases. Intervention types will not be included in the search to avoid limiting the results. We will review potentially relevant text words in the titles and abstracts of important papers in the field, thus compiling a list of terms that can be used to inform our search strategy. The literature search will be supplemented by handsearching of the reference lists of included studies for keywords and contacting methodological experts in each field. The search strategy and its iterations will be peer reviewed by a health librarian specialist using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist [ 31 ]. There will be no language restrictions and relevant articles will be translated into English as needed.

Study selection

All identified records (titles and abstracts) will be collated in a reference manager for de-duplication. The abstracts (and the full sources where abstracts are not available) will be screened by two reviewers to identify relevant literature based on our a priori inclusion criteria. Neither of the review authors will be blind to the journal titles or to the study authors or institutions, after which we will retrieve the full text of all potentially eligible articles, which will also be independently screened. Any disagreements during screening will be resolved via discussion and if needed the input of a third reviewer. The final unique set of records will be imported into an Excel file to facilitate independent screening and log disagreements between reviewers. We will also record reasons for exclusion at the full-text review stage.

We expect that some of the grey literature might subsequently be published elsewhere in the indexed literature. This will be accounted for by cross-checking authors’ names across grey literature and index literature results to identify potential duplicates.

Charting the data

We will develop a charting form to aid the collection and recording of key information using Excel, this will be done in duplicate. We will record the following:

Study populations

Intervention type, and comparator (if any); duration of the intervention

Demographics (gender, age, i.e. older/younger adolescents (10–14/15–19))

Setting (e.g. urban/rural, school/community/clinic)

Methodology

Important results

The information from research-based and non-research-based publications will be collected in separate extraction forms. Additional categories that may emerge during data extraction will be added accordingly.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

We will combine all relevant findings from the data retrieved across the various sources to create a useful summary which identifies and maps relevant interventions and their characteristics. This will include general and specific descriptions of the interventions, the population targeted, the delivery methods, the reported effectiveness and lessons learned where possible. Further, we will also extract relevant data surrounding development of the intervention and resources required. We plan to analyse the data using descriptive statistics via Microsoft Excel and report the findings narratively. If appropriate, we will include tables describing key features. If possible, and dependent on the number of studies retrieved and included, we will include a geographical map showing areas in which interventions have been used. We will also look for overlap and variations between the studies in terms of intervention type, results, setting, population targeted and follow-up timeframe. However, we will be adaptive to the data we extract and the subsequent analysis as appropriate. It should be noted that this study will not assess the quality of evidence and therefore cannot comment on the generalisability and robustness of individual studies [ 27 ]. We will report the final results using the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) [ 22 ].

Any amendments to this protocol when conducting the study will be outlined in Open Science Framework and reported in the final manuscript.

Our scoping review including an overview of reviews will systematically identify and map the interventions used to target adolescent alcohol use in Africa. Both stages of our review will be of value to a range of stakeholders in the field of adolescent alcohol use. Our characterisation of the different interventions that exist, the degree to which each has been implemented and tested and the gaps and priority research questions identified will be relevant to a variety of audiences including researchers, public health practitioners, policy makers and charity organisations.

Publication of this research protocol is in keeping with good, transparent research practise, as it reduces the risk of bias and selective reporting while providing an opportunity to strengthen our proposed review.

We do not anticipate any practical or operational issues arising that will affect the performance of this study as our research team has experience and knowledge of both the subject matter and the methodology. We will make our data available to other researchers by request. One potential limitation of this study is the difficulties that exist in categorising adolescents in terms of age; however, by including studies with participants up to the age of 24 years and stratifying our results as possible, we should capture all relevant populations as previously outlined in this protocol.

As there are no human participants involved, there will be no requirement for ethical approval. Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design of this protocol; however, the authors will work with patients and members of the public through stakeholder and other PPI research forums in disseminating the findings of the review both in the UK and the Global South.

Findings will be disseminated widely through peer-reviewed publication and in various media, for example, conferences, congresses or symposia. This review will inform other researchers in the field of adolescent health as a standalone piece of work but will also provide a baseline resource which can be used to inform future research planning.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

Assessment of the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews

Disability-adjusted life years

Heavy episodic drinking

High-income countries

Joanna Briggs Institute

Population, Concept, Context

Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews

Sustainable Development Goals

World Health Organization

Global status report on alchohol and health 2018. World Health Organisation; 2019.

Sommer M, Likindikoki S, Kaaya S. Boys’ and young men’s perspectives on violence in Northern Tanzania. Culture, health & sexuality. 2013;15(6):695–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.779031 .

Article Google Scholar

Peer N. There has been little progress in implementing comprehensive alcohol control strategies in Africa. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(6):631–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2017.1316986 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ferreira-Borges C, Parry C, Babor T. Harmful use of alcohol: a shadow over sub-Saharan Africa in need of workable solutions. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2017;14(4):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14040346 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, Arian N, Zimsen SRM, Tymeson HD, et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2 .

Spear LP. Effects of adolescent alcohol consumption on the brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2018;19(4):197–214. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2018.10 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brown SA, et al. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Supplement 4):S290–310.

Windle M, et al. Transitions into underage and problem drinking: developmental processes and mechanisms between 10 and 15 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Supplement 4):S273–89.

Sommer M, Likindikoki S, Kaaya S. Tanzanian adolescent boys’ transitions through puberty: the importance of context. American journal of public health. 2014;104(12):2290–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302178 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tanner-Smith EE, Lipsey MW. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2015;51:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2014.09.001 .

Yuma-Guerrero PJ, Lawson KA, Velasquez MM, von Sternberg K, Maxson T, Garcia N. Screening, brief intervention, and referral for alcohol use in adolescents: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):115–22. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1589 .

Foxcroft DR, Tsertsvadze A. Universal school‐based prevention programs for alcohol misuse in young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(5):CD009113. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009113 .

Derges J, Kidger J, Fox F, Campbell R, Kaner E, Hickman M. Alcohol screening and brief interventions for adults and young people in health and community-based settings: a qualitative systematic literature review. BMC public health. 2017;17(1):562. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4476-4 .

Foxcroft DR, Tsertsvadze A. Universal alcohol misuse prevention programmes for children and adolescents: Cochrane systematic reviews. Perspect Public Health. 2012;132(3):128–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913912443487 .

Perry CL, Grant M. Comparing peer-led to teacher-led youth alcohol education in four countries. Alcohol Res Health. 1988;12(4):322.

Google Scholar

Das JK, Salam RA, Arshad A, Finkelstein Y, Bhutta ZA. Interventions for adolescent substance abuse: an overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59(4):S61–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.021 .

Salam RA, Das JK, Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA. Adolescent health interventions: conclusions, evidence gaps, and research priorities . Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016; 59 (4):S88–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.006 .

Sudhinaraset M, Wigglesworth C, Takeuchi DT. Social and cultural contexts of alcohol use: influences in a social–ecological framework. Alcohol research: current reviews; 2016.

Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry. 1993;56(1):96–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624 .

Page MJ, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Hoffmann T, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. MetaArXiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/v7gm2 .

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, Langlois EV, O'Brien KK, Horsley T, et al. Reporting scoping reviews—PRISMA ScR extension . Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2020;123:177–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.016 .

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 .

Munn Z, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Method. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 .

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Bmj. 2014;348(mar07 3):g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687 .

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 .

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 .

The Joanna Briggs Institute, ‘The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 Edition'. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014.

Peters M, Godfrey C, Khalil H. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ manual: methodology for JBI scoping review. Adelaide, Australia; 2015.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;75:40–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Camila Olarte Parra, Alison Derbyshire and Professor Paul Garner for providing advice during the writing of this protocol.

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (project reference 16/136/35) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had or will have no role in the development of this protocol, the collection and analyses, or interpretation of results, or in the writing or publication of the review’s results.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of International Public Health, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place, Liverpool, UK

Alice M. Biggane, Eleanor Briegal & Angela Obasi

AXESS Sexual Health, Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK

Angela Obasi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have made substantive intellectual contributions to the development of this protocol. AB, EB and AIO jointly conceived the idea for the project. AB, EB and AIO contributed to the study design and development of research questions. AB conceptualised the review approach and led the writing of the manuscript. AIO led the supervision of the manuscript preparation. All authors provided detailed comments on earlier drafts and approved this manuscript. AIO is guarantor of this review.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Angela Obasi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

None of the authors have any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information