Peer Recognized

Make a name in academia

How to Write a Research Paper: the LEAP approach (+cheat sheet)

In this article I will show you how to write a research paper using the four LEAP writing steps. The LEAP academic writing approach is a step-by-step method for turning research results into a published paper .

The LEAP writing approach has been the cornerstone of the 70 + research papers that I have authored and the 3700+ citations these paper have accumulated within 9 years since the completion of my PhD. I hope the LEAP approach will help you just as much as it has helped me to make an real, tangible impact with my research.

What is the LEAP research paper writing approach?

I designed the LEAP writing approach not only for merely writing the papers. My goal with the writing system was to show young scientists how to first think about research results and then how to efficiently write each section of the research paper.

In other words, you will see how to write a research paper by first analyzing the results and then building a logical, persuasive arguments. In this way, instead of being afraid of writing research paper, you will be able to rely on the paper writing process to help you with what is the most demanding task in getting published – thinking.

The four research paper writing steps according to the LEAP approach:

I will show each of these steps in detail. And you will be able to download the LEAP cheat sheet for using with every paper you write.

But before I tell you how to efficiently write a research paper, I want to show you what is the problem with the way scientists typically write a research paper and why the LEAP approach is more efficient.

How scientists typically write a research paper (and why it isn’t efficient)

Writing a research paper can be tough, especially for a young scientist. Your reasoning needs to be persuasive and thorough enough to convince readers of your arguments. The description has to be derived from research evidence, from prior art, and from your own judgment. This is a tough feat to accomplish.

The figure below shows the sequence of the different parts of a typical research paper. Depending on the scientific journal, some sections might be merged or nonexistent, but the general outline of a research paper will remain very similar.

Here is the problem: Most people make the mistake of writing in this same sequence.

While the structure of scientific articles is designed to help the reader follow the research, it does little to help the scientist write the paper. This is because the layout of research articles starts with the broad (introduction) and narrows down to the specifics (results). See in the figure below how the research paper is structured in terms of the breath of information that each section entails.

How to write a research paper according to the LEAP approach

For a scientist, it is much easier to start writing a research paper with laying out the facts in the narrow sections (i.e. results), step back to describe them (i.e. write the discussion), and step back again to explain the broader picture in the introduction.

For example, it might feel intimidating to start writing a research paper by explaining your research’s global significance in the introduction, while it is easy to plot the figures in the results. When plotting the results, there is not much room for wiggle: the results are what they are.

Starting to write a research papers from the results is also more fun because you finally get to see and understand the complete picture of the research that you have worked on.

Most importantly, following the LEAP approach will help you first make sense of the results yourself and then clearly communicate them to the readers. That is because the sequence of writing allows you to slowly understand the meaning of the results and then develop arguments for presenting to your readers.

I have personally been able to write and submit a research article in three short days using this method.

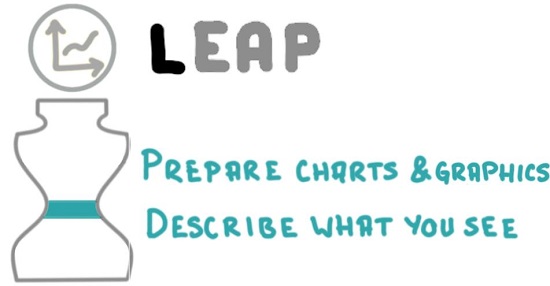

Step 1: Lay Out the Facts

You have worked long hours on a research project that has produced results and are no doubt curious to determine what they exactly mean. There is no better way to do this than by preparing figures, graphics and tables. This is what the first LEAP step is focused on – diving into the results.

How to p repare charts and tables for a research paper

Your first task is to try out different ways of visually demonstrating the research results. In many fields, the central items of a journal paper will be charts that are based on the data generated during research. In other fields, these might be conceptual diagrams, microscopy images, schematics and a number of other types of scientific graphics which should visually communicate the research study and its results to the readers. If you have reasonably small number of data points, data tables might be useful as well.

Tips for preparing charts and tables

- Try multiple chart types but in the finished paper only use the one that best conveys the message you want to present to the readers

- Follow the eight chart design progressions for selecting and refining a data chart for your paper: https://peerrecognized.com/chart-progressions

- Prepare scientific graphics and visualizations for your paper using the scientific graphic design cheat sheet: https://peerrecognized.com/tools-for-creating-scientific-illustrations/

How to describe the results of your research

Now that you have your data charts, graphics and tables laid out in front of you – describe what you see in them. Seek to answer the question: What have I found? Your statements should progress in a logical sequence and be backed by the visual information. Since, at this point, you are simply explaining what everyone should be able to see for themselves, you can use a declarative tone: The figure X demonstrates that…

Tips for describing the research results :

- Answer the question: “ What have I found? “

- Use declarative tone since you are simply describing observations

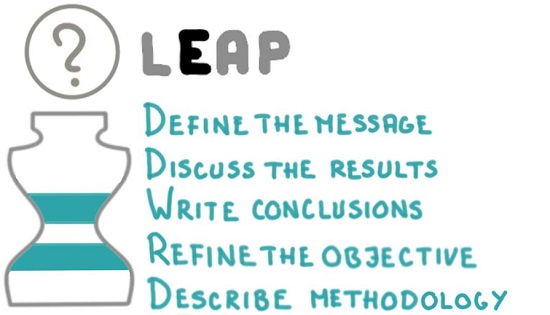

Step 2: Explain the results

The core aspect of your research paper is not actually the results; it is the explanation of their meaning. In the second LEAP step, you will do some heavy lifting by guiding the readers through the results using logic backed by previous scientific research.

How to define the Message of a research paper

To define the central message of your research paper, imagine how you would explain your research to a colleague in 20 seconds . If you succeed in effectively communicating your paper’s message, a reader should be able to recount your findings in a similarly concise way even a year after reading it. This clarity will increase the chances that someone uses the knowledge you generated, which in turn raises the likelihood of citations to your research paper.

Tips for defining the paper’s central message :

- Write the paper’s core message in a single sentence or two bullet points

- Write the core message in the header of the research paper manuscript

How to write the Discussion section of a research paper

In the discussion section you have to demonstrate why your research paper is worthy of publishing. In other words, you must now answer the all-important So what? question . How well you do so will ultimately define the success of your research paper.

Here are three steps to get started with writing the discussion section:

- Write bullet points of the things that convey the central message of the research article (these may evolve into subheadings later on).

- Make a list with the arguments or observations that support each idea.

- Finally, expand on each point to make full sentences and paragraphs.

Tips for writing the discussion section:

- What is the meaning of the results?

- Was the hypothesis confirmed?

- Write bullet points that support the core message

- List logical arguments for each bullet point, group them into sections

- Instead of repeating research timeline, use a presentation sequence that best supports your logic

- Convert arguments to full paragraphs; be confident but do not overhype

- Refer to both supportive and contradicting research papers for maximum credibility

How to write the Conclusions of a research paper

Since some readers might just skim through your research paper and turn directly to the conclusions, it is a good idea to make conclusion a standalone piece. In the first few sentences of the conclusions, briefly summarize the methodology and try to avoid using abbreviations (if you do, explain what they mean).

After this introduction, summarize the findings from the discussion section. Either paragraph style or bullet-point style conclusions can be used. I prefer the bullet-point style because it clearly separates the different conclusions and provides an easy-to-digest overview for the casual browser. It also forces me to be more succinct.

Tips for writing the conclusion section :

- Summarize the key findings, starting with the most important one

- Make conclusions standalone (short summary, avoid abbreviations)

- Add an optional take-home message and suggest future research in the last paragraph

How to refine the Objective of a research paper

The objective is a short, clear statement defining the paper’s research goals. It can be included either in the final paragraph of the introduction, or as a separate subsection after the introduction. Avoid writing long paragraphs with in-depth reasoning, references, and explanation of methodology since these belong in other sections. The paper’s objective can often be written in a single crisp sentence.

Tips for writing the objective section :

- The objective should ask the question that is answered by the central message of the research paper

- The research objective should be clear long before writing a paper. At this point, you are simply refining it to make sure it is addressed in the body of the paper.

How to write the Methodology section of your research paper

When writing the methodology section, aim for a depth of explanation that will allow readers to reproduce the study . This means that if you are using a novel method, you will have to describe it thoroughly. If, on the other hand, you applied a standardized method, or used an approach from another paper, it will be enough to briefly describe it with reference to the detailed original source.

Remember to also detail the research population, mention how you ensured representative sampling, and elaborate on what statistical methods you used to analyze the results.

Tips for writing the methodology section :

- Include enough detail to allow reproducing the research

- Provide references if the methods are known

- Create a methodology flow chart to add clarity

- Describe the research population, sampling methodology, statistical methods for result analysis

- Describe what methodology, test methods, materials, and sample groups were used in the research.

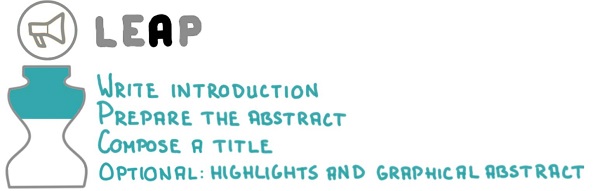

Step 3: Advertize the research

Step 3 of the LEAP writing approach is designed to entice the casual browser into reading your research paper. This advertising can be done with an informative title, an intriguing abstract, as well as a thorough explanation of the underlying need for doing the research within the introduction.

How to write the Introduction of a research paper

The introduction section should leave no doubt in the mind of the reader that what you are doing is important and that this work could push scientific knowledge forward. To do this convincingly, you will need to have a good knowledge of what is state-of-the-art in your field. You also need be able to see the bigger picture in order to demonstrate the potential impacts of your research work.

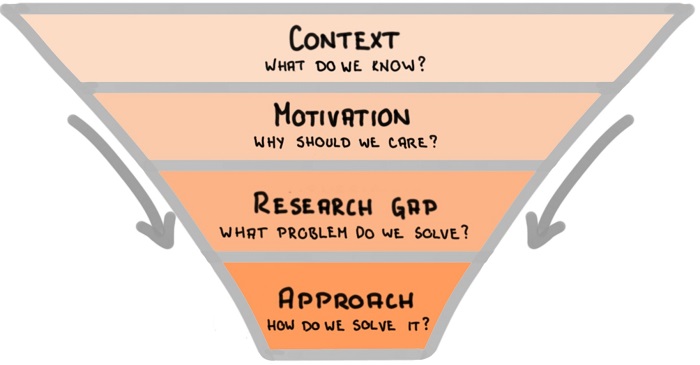

Think of the introduction as a funnel, going from wide to narrow, as shown in the figure below:

- Start with a brief context to explain what do we already know,

- Follow with the motivation for the research study and explain why should we care about it,

- Explain the research gap you are going to bridge within this research paper,

- Describe the approach you will take to solve the problem.

Tips for writing the introduction section :

- Follow the Context – Motivation – Research gap – Approach funnel for writing the introduction

- Explain how others tried and how you plan to solve the research problem

- Do a thorough literature review before writing the introduction

- Start writing the introduction by using your own words, then add references from the literature

How to prepare the Abstract of a research paper

The abstract acts as your paper’s elevator pitch and is therefore best written only after the main text is finished. In this one short paragraph you must convince someone to take on the time-consuming task of reading your whole research article. So, make the paper easy to read, intriguing, and self-explanatory; avoid jargon and abbreviations.

How to structure the abstract of a research paper:

- The abstract is a single paragraph that follows this structure:

- Problem: why did we research this

- Methodology: typically starts with the words “Here we…” that signal the start of own contribution.

- Results: what we found from the research.

- Conclusions: show why are the findings important

How to compose a research paper Title

The title is the ultimate summary of a research paper. It must therefore entice someone looking for information to click on a link to it and continue reading the article. A title is also used for indexing purposes in scientific databases, so a representative and optimized title will play large role in determining if your research paper appears in search results at all.

Tips for coming up with a research paper title:

- Capture curiosity of potential readers using a clear and descriptive title

- Include broad terms that are often searched

- Add details that uniquely identify the researched subject of your research paper

- Avoid jargon and abbreviations

- Use keywords as title extension (instead of duplicating the words) to increase the chance of appearing in search results

How to prepare Highlights and Graphical Abstract

Highlights are three to five short bullet-point style statements that convey the core findings of the research paper. Notice that the focus is on the findings, not on the process of getting there.

A graphical abstract placed next to the textual abstract visually summarizes the entire research paper in a single, easy-to-follow figure. I show how to create a graphical abstract in my book Research Data Visualization and Scientific Graphics.

Tips for preparing highlights and graphical abstract:

- In highlights show core findings of the research paper (instead of what you did in the study).

- In graphical abstract show take-home message or methodology of the research paper. Learn more about creating a graphical abstract in this article.

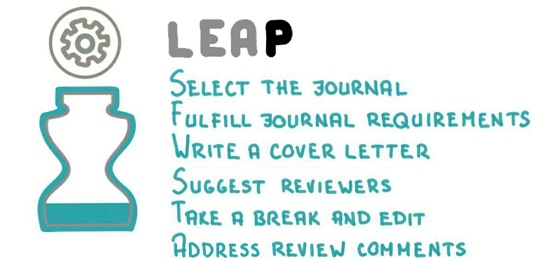

Step 4: Prepare for submission

Sometimes it seems that nuclear fusion will stop on the star closest to us (read: the sun will stop to shine) before a submitted manuscript is published in a scientific journal. The publication process routinely takes a long time, and after submitting the manuscript you have very little control over what happens. To increase the chances of a quick publication, you must do your homework before submitting the manuscript. In the fourth LEAP step, you make sure that your research paper is published in the most appropriate journal as quickly and painlessly as possible.

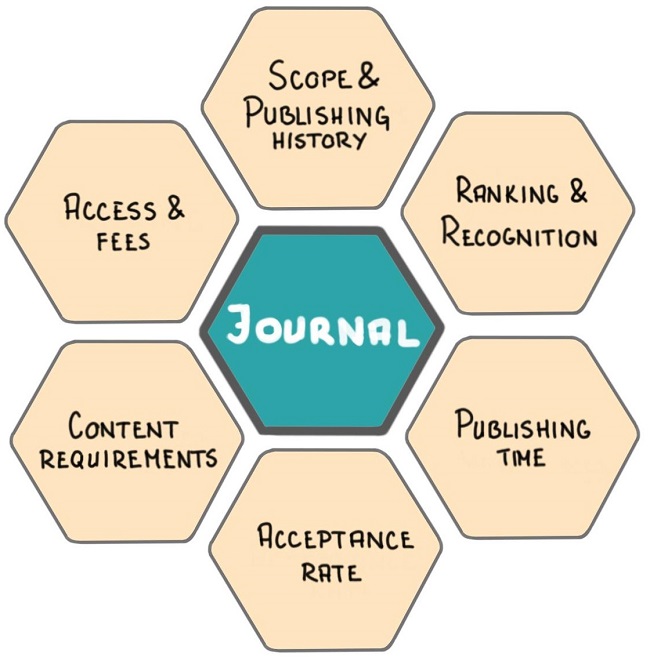

How to select a scientific Journal for your research paper

The best way to find a journal for your research paper is it to review which journals you used while preparing your manuscript. This source listing should provide some assurance that your own research paper, once published, will be among similar articles and, thus, among your field’s trusted sources.

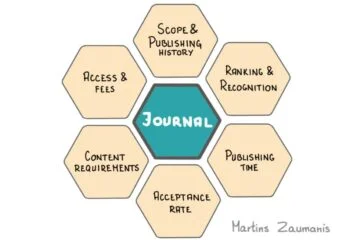

After this initial selection of hand-full of scientific journals, consider the following six parameters for selecting the most appropriate journal for your research paper (read this article to review each step in detail):

- Scope and publishing history

- Ranking and Recognition

- Publishing time

- Acceptance rate

- Content requirements

- Access and Fees

How to select a journal for your research paper:

- Use the six parameters to select the most appropriate scientific journal for your research paper

- Use the following tools for journal selection: https://peerrecognized.com/journals

- Follow the journal’s “Authors guide” formatting requirements

How to Edit you manuscript

No one can write a finished research paper on their first attempt. Before submitting, make sure to take a break from your work for a couple of days, or even weeks. Try not to think about the manuscript during this time. Once it has faded from your memory, it is time to return and edit. The pause will allow you to read the manuscript from a fresh perspective and make edits as necessary.

I have summarized the most useful research paper editing tools in this article.

Tips for editing a research paper:

- Take time away from the research paper to forget about it; then returning to edit,

- Start by editing the content: structure, headings, paragraphs, logic, figures

- Continue by editing the grammar and language; perform a thorough language check using academic writing tools

- Read the entire paper out loud and correct what sounds weird

How to write a compelling Cover Letter for your paper

Begin the cover letter by stating the paper’s title and the type of paper you are submitting (review paper, research paper, short communication). Next, concisely explain why your study was performed, what was done, and what the key findings are. State why the results are important and what impact they might have in the field. Make sure you mention how your approach and findings relate to the scope of the journal in order to show why the article would be of interest to the journal’s readers.

I wrote a separate article that explains what to include in a cover letter here. You can also download a cover letter template from the article.

Tips for writing a cover letter:

- Explain how the findings of your research relate to journal’s scope

- Tell what impact the research results will have

- Show why the research paper will interest the journal’s audience

- Add any legal statements as required in journal’s guide for authors

How to Answer the Reviewers

Reviewers will often ask for new experiments, extended discussion, additional details on the experimental setup, and so forth. In principle, your primary winning tactic will be to agree with the reviewers and follow their suggestions whenever possible. After all, you must earn their blessing in order to get your paper published.

Be sure to answer each review query and stick to the point. In the response to the reviewers document write exactly where in the paper you have made any changes. In the paper itself, highlight the changes using a different color. This way the reviewers are less likely to re-read the entire article and suggest new edits.

In cases when you don’t agree with the reviewers, it makes sense to answer more thoroughly. Reviewers are scientifically minded people and so, with enough logical and supported argument, they will eventually be willing to see things your way.

Tips for answering the reviewers:

- Agree with most review comments, but if you don’t, thoroughly explain why

- Highlight changes in the manuscript

- Do not take the comments personally and cool down before answering

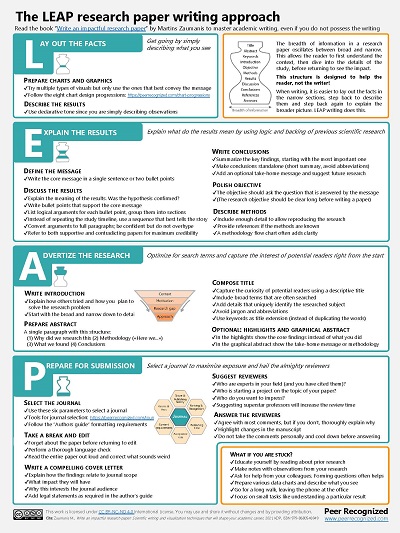

The LEAP research paper writing cheat sheet

Imagine that you are back in grad school and preparing to take an exam on the topic: “How to write a research paper”. As an exemplary student, you would, most naturally, create a cheat sheet summarizing the subject… Well, I did it for you.

This one-page summary of the LEAP research paper writing technique will remind you of the key research paper writing steps. Print it out and stick it to a wall in your office so that you can review it whenever you are writing a new research paper.

Now that we have gone through the four LEAP research paper writing steps, I hope you have a good idea of how to write a research paper. It can be an enjoyable process and once you get the hang of it, the four LEAP writing steps should even help you think about and interpret the research results. This process should enable you to write a well-structured, concise, and compelling research paper.

Have fund with writing your next research paper. I hope it will turn out great!

Learn writing papers that get cited

The LEAP writing approach is a blueprint for writing research papers. But to be efficient and write papers that get cited, you need more than that.

My name is Martins Zaumanis and in my interactive course Research Paper Writing Masterclass I will show you how to visualize your research results, frame a message that convinces your readers, and write each section of the paper. Step-by-step.

And of course – you will learn to respond the infamous Reviewer No.2.

Hey! My name is Martins Zaumanis and I am a materials scientist in Switzerland ( Google Scholar ). As the first person in my family with a PhD, I have first-hand experience of the challenges starting scientists face in academia. With this blog, I want to help young researchers succeed in academia. I call the blog “Peer Recognized”, because peer recognition is what lifts academic careers and pushes science forward.

Besides this blog, I have written the Peer Recognized book series and created the Peer Recognized Academy offering interactive online courses.

Related articles:

One comment

- Pingback: Research Paper Outline with Key Sentence Skeleton (+Paper Template)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

I want to join the Peer Recognized newsletter!

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Copyright © 2024 Martins Zaumanis

Contacts: [email protected]

Privacy Policy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major components of a research paper written using American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Apply general APA style and formatting conventions in a research paper.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use APA style , the documentation and formatting style followed by the American Psychological Association, as well as MLA style , from the Modern Language Association. There are a few major formatting styles used in academic texts, including AMA, Chicago, and Turabian:

- AMA (American Medical Association) for medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA (American Psychological Association) for education, psychology, and the social sciences

- Chicago—a common style used in everyday publications like magazines, newspapers, and books

- MLA (Modern Language Association) for English, literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—another common style designed for its universal application across all subjects and disciplines

While all the formatting and citation styles have their own use and applications, in this chapter we focus our attention on the two styles you are most likely to use in your academic studies: APA and MLA.

If you find that the rules of proper source documentation are difficult to keep straight, you are not alone. Writing a good research paper is, in and of itself, a major intellectual challenge. Having to follow detailed citation and formatting guidelines as well may seem like just one more task to add to an already-too-long list of requirements.

Following these guidelines, however, serves several important purposes. First, it signals to your readers that your paper should be taken seriously as a student’s contribution to a given academic or professional field; it is the literary equivalent of wearing a tailored suit to a job interview. Second, it shows that you respect other people’s work enough to give them proper credit for it. Finally, it helps your reader find additional materials if he or she wishes to learn more about your topic.

Furthermore, producing a letter-perfect APA-style paper need not be burdensome. Yes, it requires careful attention to detail. However, you can simplify the process if you keep these broad guidelines in mind:

- Work ahead whenever you can. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” includes tips for keeping track of your sources early in the research process, which will save time later on.

- Get it right the first time. Apply APA guidelines as you write, so you will not have much to correct during the editing stage. Again, putting in a little extra time early on can save time later.

- Use the resources available to you. In addition to the guidelines provided in this chapter, you may wish to consult the APA website at http://www.apa.org or the Purdue University Online Writing lab at http://owl.english.purdue.edu , which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

General Formatting Guidelines

This chapter provides detailed guidelines for using the citation and formatting conventions developed by the American Psychological Association, or APA. Writers in disciplines as diverse as astrophysics, biology, psychology, and education follow APA style. The major components of a paper written in APA style are listed in the following box.

These are the major components of an APA-style paper:

Body, which includes the following:

- Headings and, if necessary, subheadings to organize the content

- In-text citations of research sources

- References page

All these components must be saved in one document, not as separate documents.

The title page of your paper includes the following information:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Name of the institution with which the author is affiliated

- Header at the top of the page with the paper title (in capital letters) and the page number (If the title is lengthy, you may use a shortened form of it in the header.)

List the first three elements in the order given in the previous list, centered about one third of the way down from the top of the page. Use the headers and footers tool of your word-processing program to add the header, with the title text at the left and the page number in the upper-right corner. Your title page should look like the following example.

The next page of your paper provides an abstract , or brief summary of your findings. An abstract does not need to be provided in every paper, but an abstract should be used in papers that include a hypothesis. A good abstract is concise—about one hundred fifty to two hundred fifty words—and is written in an objective, impersonal style. Your writing voice will not be as apparent here as in the body of your paper. When writing the abstract, take a just-the-facts approach, and summarize your research question and your findings in a few sentences.

In Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” , you read a paper written by a student named Jorge, who researched the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets. Read Jorge’s abstract. Note how it sums up the major ideas in his paper without going into excessive detail.

Write an abstract summarizing your paper. Briefly introduce the topic, state your findings, and sum up what conclusions you can draw from your research. Use the word count feature of your word-processing program to make sure your abstract does not exceed one hundred fifty words.

Depending on your field of study, you may sometimes write research papers that present extensive primary research, such as your own experiment or survey. In your abstract, summarize your research question and your findings, and briefly indicate how your study relates to prior research in the field.

Margins, Pagination, and Headings

APA style requirements also address specific formatting concerns, such as margins, pagination, and heading styles, within the body of the paper. Review the following APA guidelines.

Use these general guidelines to format the paper:

- Set the top, bottom, and side margins of your paper at 1 inch.

- Use double-spaced text throughout your paper.

- Use a standard font, such as Times New Roman or Arial, in a legible size (10- to 12-point).

- Use continuous pagination throughout the paper, including the title page and the references section. Page numbers appear flush right within your header.

- Section headings and subsection headings within the body of your paper use different types of formatting depending on the level of information you are presenting. Additional details from Jorge’s paper are provided.

Begin formatting the final draft of your paper according to APA guidelines. You may work with an existing document or set up a new document if you choose. Include the following:

- Your title page

- The abstract you created in Note 13.8 “Exercise 1”

- Correct headers and page numbers for your title page and abstract

APA style uses section headings to organize information, making it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought and to know immediately what major topics are covered. Depending on the length and complexity of the paper, its major sections may also be divided into subsections, sub-subsections, and so on. These smaller sections, in turn, use different heading styles to indicate different levels of information. In essence, you are using headings to create a hierarchy of information.

The following heading styles used in APA formatting are listed in order of greatest to least importance:

- Section headings use centered, boldface type. Headings use title case, with important words in the heading capitalized.

- Subsection headings use left-aligned, boldface type. Headings use title case.

- The third level uses left-aligned, indented, boldface type. Headings use a capital letter only for the first word, and they end in a period.

- The fourth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are boldfaced and italicized.

- The fifth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are italicized and not boldfaced.

Visually, the hierarchy of information is organized as indicated in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” .

Table 13.1 Section Headings

| Level of Information | Text Example |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | |

| Level 2 | |

| Level 3 | |

| Level 4 | |

| Level 5 |

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” , but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice. Longer or more complex papers may need level 2 headings or other lower-level headings to organize information clearly. Use your outline to craft your major section headings and determine whether any subtopics are substantial enough to require additional levels of headings.

Working with the document you developed in Note 13.11 “Exercise 2” , begin setting up the heading structure of the final draft of your research paper according to APA guidelines. Include your title and at least two to three major section headings, and follow the formatting guidelines provided above. If your major sections should be broken into subsections, add those headings as well. Use your outline to help you.

Because Jorge used only level 1 headings, his Exercise 3 would look like the following:

| Level of Information | Text Example |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 |

Citation Guidelines

In-text citations.

Throughout the body of your paper, include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. As you learned in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , the purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; each source you cite will have a longer entry in the references section that provides more detailed information.

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, it is also required that you include the page number where the quote appears in your citation.

This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can choose the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually a straightforward task. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.2 “Citing and Referencing Techniques” and Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provide extensive guidelines for citing a variety of source types.

Writing at Work

APA is just one of several different styles with its own guidelines for documentation, formatting, and language usage. Depending on your field of interest, you may be exposed to additional styles, such as the following:

- MLA style. Determined by the Modern Languages Association and used for papers in literature, languages, and other disciplines in the humanities.

- Chicago style. Outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style and sometimes used for papers in the humanities and the sciences; many professional organizations use this style for publications as well.

- Associated Press (AP) style. Used by professional journalists.

References List

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive bibliographical information. Again, this information allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

The specific format of entries in the list of references varies slightly for different source types, but the entries generally include the following information:

- The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

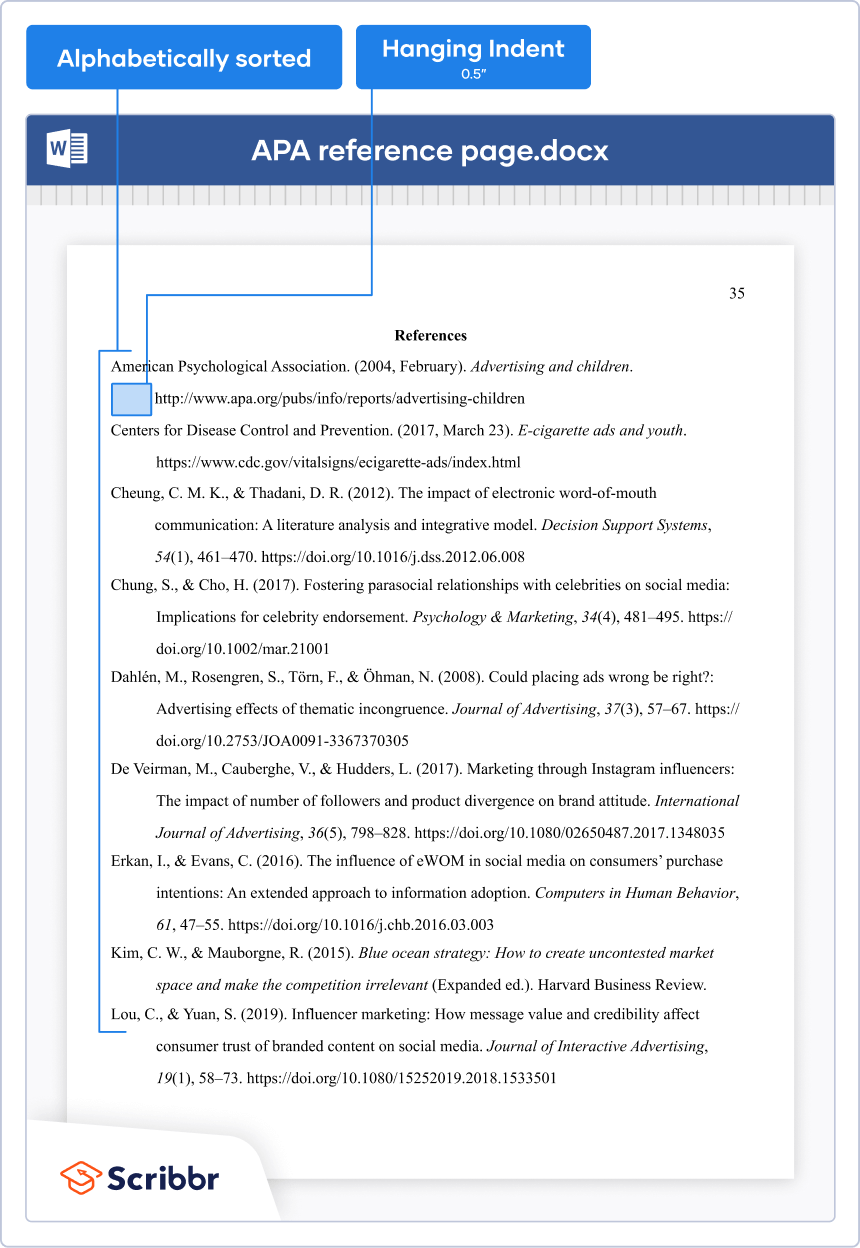

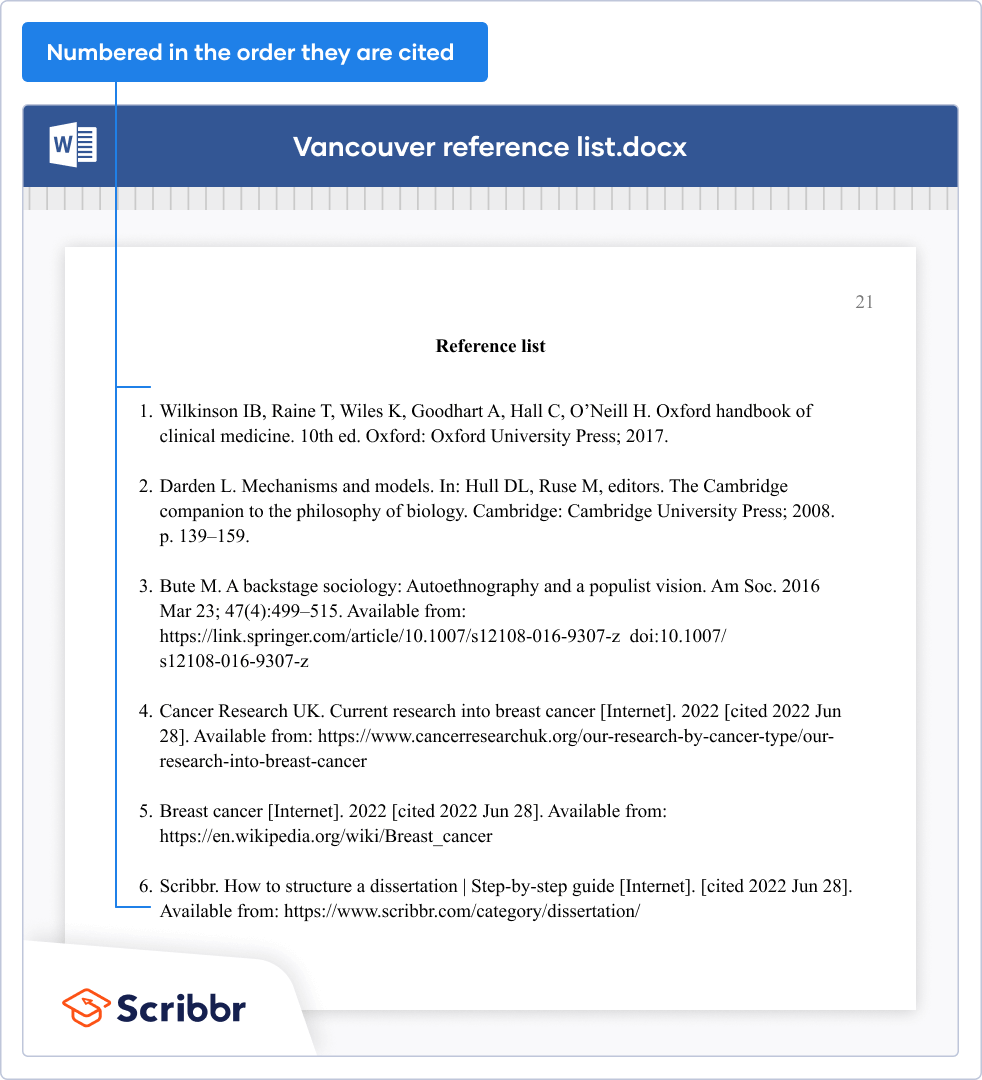

The references page is double spaced and lists entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces. Review the following example. ( Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provides extensive guidelines for formatting reference entries for different types of sources.)

In APA style, book and article titles are formatted in sentence case, not title case. Sentence case means that only the first word is capitalized, along with any proper nouns.

Key Takeaways

- Following proper citation and formatting guidelines helps writers ensure that their work will be taken seriously, give proper credit to other authors for their work, and provide valuable information to readers.

- Working ahead and taking care to cite sources correctly the first time are ways writers can save time during the editing stage of writing a research paper.

- APA papers usually include an abstract that concisely summarizes the paper.

- APA papers use a specific headings structure to provide a clear hierarchy of information.

- In APA papers, in-text citations usually include the name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

- In-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, which provide detailed bibliographical information about a source.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Paper Format

Consistency in the order, structure, and format of a paper allows readers to focus on a paper’s content rather than its presentation.

To format a paper in APA Style, writers can typically use the default settings and automatic formatting tools of their word-processing program or make only minor adjustments.

The guidelines for paper format apply to both student assignments and manuscripts being submitted for publication to a journal. If you are using APA Style to create another kind of work (e.g., a website, conference poster, or PowerPoint presentation), you may need to format your work differently in order to optimize its presentation, for example, by using different line spacing and font sizes. Follow the guidelines of your institution or publisher to adapt APA Style formatting guidelines as needed.

Academic Writer ®

Master academic writing with APA’s essential teaching and learning resource

Course Adoption

Teaching APA Style? Become a course adopter of the 7th edition Publication Manual

Instructional Aids

Guides, checklists, webinars, tutorials, and sample papers for anyone looking to improve their knowledge of APA Style

Formatting Your Research Project

To learn how to set up your research project in MLA format, visit our free sample chapter on MLA Handbook Plus , the only authorized subscription-based digital resource featuring the MLA Handbook, available for unlimited simultaneous users at subscribing institutions.

CoB Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU)

- Learn More About a Topic

- Find Scholarly Articles

- Use Scholarly Articles

- Organizing Your Research

- Cite Your Sources

- Libraries Events - Reading Purple

Question? Ask me!

Learn More About Your Research Topic

- Get started with reviewing the literature

- A literature review is NOT...

- Types of literature reviews

- Finding published literature reviews

A literature review examines existing contributions around a topic, question, or issue in a field of study. These contributions can include peer reviewed articles, books, and other published research. Literature reviews can be used to give an overview of a field of research to describe theories, explore methodologies, and discuss developments in a field by drawing on research from multiple studies.

A literature review can be used to:

- Ground yourself in a topic and learn more about it

- Find new ideas to explore

- Discover existing research (so you do not repeat it)

- Determine what methodologies have already been used to research a topic

- Discover flaws, problems, and gaps that exist in the literature

- Critique or evaluate existing research on a topic

- Situate your research in a larger context or advocate for your research by demonstrating that you are extending upon existing knowledge

What makes a good literature review?

A good literature review has a clear scope - don't try to collect everything about a topic that has ever been published! Instead focus in on what you want to know more about your specific research topic. A good literature review might also:

- Cover all important relevant literature - if you are finding too many sources, try narrowing in on key authors and well cited-research

- Is up-to-date - limit your review to a certain time period

- Provide an insightful analysis of the ideas and conclusions in the literature

- Point out similarities and differences, strengths and weaknesses in the literature

- Identify gaps in the literature for future research - or to set up your own research as relevant!

- Provides the context for which the literature is important - what impact does the literature have on countries, people, industries, etc.

- Systematic Review: AI's Impact on Higher Education - Learning, Teaching, and Career Opportunities Review this example to learn one way a literature review can be written.

A well conducted literature review can set up your final research product. Many researchers will write literature reviews at the beginning of their research article to situate their research within the larger context in their field or topic. This demonstrates that they have awareness of their topic and how they are building upon the topic. Keeping good notes when you are conducting your review can help set you up for success when you begin work on your final research product. When conducting your literature review AVOID:

- Summarizing articles INSTEAD draw connections between different articles

- Creating a chronological account of a topic INSTEAD focus on current literature or foundational works

- Sharing personal opinions on whether or not you liked articles INSTEAD ask questions

A strong literature review organizes existing contributions to a conversation into categories or “themes.” There are multiple ways to approach targeting a literature review to achieve your specific learning goals. Common types of reviews include:

Traditional Review

- Analyzes, synthesizes, and critiques a body of literature

- Identifies patterns and themes in the literature

- Draws conclusions from the literature

- Identifies gaps in literature

Argumentative Review

- Examines literature selectively in order to support or refuse an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature

Historical Review

- Examines research throughout a period of time

- Places research in a historical context

Integrative Review

- Aims to review, critique, and synthesize literature on a topic in an integrated way that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated

- Might include case studies, observational studies, and meta-analysis, as well as other types of research

Methodological Review

- Focuses on method of analysis (how researchers came to the idea) rather than on findings (their final conclusions and what they found)

Published literature reviews are called review articles, however, research articles often contain brief literature reviews at the beginning to give context to the study within that article.

By reviewing published literature reviews you can more easily ground yourself in a topic, it's main themes, and find relevant literature for your own review.

Tip: When identifying main themes related to your topic, look at the headers in a research article. Some authors choose to list their literature review themes as headers to organize their review. Others might choose to name their themes in the first few sentences of each paragraph in their review. Sometimes a literature review, especially if it is brief, will be included in the introduction or some other beginning part of the article.

Approaching a Literature Review

- Evidenced-based approach

An Evidence-Based Management Framework can help direct your literature review process.

"Evidence-Based" is a term that was originally coined in the 1990s in the field of medicine, but today its principles extend across disciplines as varied as education, social work, public work, and management. Evidence-Based Management focuses on improving decision-making process.

While conducting a literature review, we need to gather evidence and summarize it to support our decisions and conclusions regarding the topic or problem. We recommend you use a 4 step approach of the Evidence-Based Management Framework while working on a literature review.

During the "Ask" step , you need to define a specific topic, thesis, problem, or research question that your literature review will be focusing on.

It may require first to gain some knowledge about the area or discipline that your topic, thesis, problem, or research question originate from. At this moment, think about a type of a literature review you plan to work on. For example are you reviewing the literature to educate yourself on a topic, to plan to write a literature review article, or to prepare to situate your research project within the broader literature?

Use this to determine the scope of your literature review and the type of publications you need to use (e.g., journals, books, governmental documents, conference proceedings, dissertations, training materials, and etc.).

A few other questions you might ask are:

- Is my topic, question, or problem narrowed enough to exclude irrelevant material?

- What is the number of sources to use to fulfill the research need and represent the scope? i.e. is the topic narrow enough that you want to find everything that exists or broad enough that you only want to see what a few experts have to say?

- What facets of a topic are the focus? Am I looking at issues of theory? methodology? policy? quantitative research? or qualitative research?

During the “Acquire” step , you are actively gathering evidence and information that relates to your topic or problem.

This is when you search for related scholarly articles, books, dissertations, and etc. to see “what has been done” and “what we already know” about the topic or problem. While doing a literature review in business, you may also find it helpful to review various websites such as professional associations, government websites offering industry data, companies’ data, conference proceedings, or training materials. It may increase your understanding about the current state of the knowledge in your topic or problem.

During this step, you should keep a careful records of the literature and website resources you review.

During the “Appraise” step, you actively evaluate the sources used to acquire the information. To make decisions regarding the relevance and trustworthiness of the sources and information, you can ask the following questions:

- Is the source reputable? (e.g., peer-reviewed journals and government websites typically offer more trustworthy information)

- How old (dated) is the source? Is it still current, or is there newer updated information that you might be able to find?

- How closely does the source match the topic / problem / issue you are researching?

During this step, you may decide to eliminate some of the material you gathered during the “Acquire” step . Similarly, you may find that you need to engage in additional searches to find information that suits your needs. This is normal—the process of the "Appraisal" step often uncovers new keywords and new potential sources.

During the “Aggregate” step , you “pull together” the information you deemed trustworthy and relevant. The information gathered and evaluated needs to be summarized in a narrative form—a summary of your findings.

While summarizing and aggregating information, use synthesis language like this:

- Much of the literature on [topic X] focuses on [major themes] .

- In recent years, researchers have begun investigating [facets A, B, and C] of [topic X] .

- The studies in this review of [topic X] confirm / suggest / call into question / support [idea / practice / finding / method / theory / guideline Y].

- In the reviewed studies [variable X] was generally associated with higher / lower rates of [outcome Y].

- A limitation of some / most / all of these studies is [Y].

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Find Scholarly Articles >>

- Last Updated: Sep 27, 2024 11:54 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.jmu.edu/reu

Redirect Notice

Page limits.

Follow the page limits specified below for the attachments in your grant application, unless otherwise specified in the notice of funding opportunity (NOFO) or related NIH Guide notice. Funding opportunity instructions always supersede general application guide instructions and NIH Guide notice information supersedes both the funding opportunity and the application guide.

If no page limit is listed in the table below, in Section IV of the NOFO under Page Limitations, or in a related notice, you can assume the attachment does not have a limit. When preparing an administrative supplement request, follow the appropriate page limits for the activity code of parent award.

Standard page limits are organized by Activity Code

- Fellowship (F) Applications

- Individual Career Development Award (K, excluding K12) Applications

- Institutional Training (T), International Training (D43, D71, U2R), Institutional Career Awards (K12, KL2), and Research Education (R25, UE5,R38, DP7) Applications

- S10, R01, U01, R03, R21, and all other applications

For all Fellowship (F) Applications

Including F05, F30, F31, F32, F33, F37, F38, F99/K00

If no page limit is listed in the table below, in Section IV of the NOFO under Page Limitations, or in a related notice, you can assume the attachment does not have a limit.

| Section of Application | Page Limits* (Unless the funding opportunity specifies a different limit) |

|---|---|

| 30 lines of text | |

| Three sentences | |

| (when applicable) | 1 |

6 | |

1 | |

6 | |

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

6 | |

6 | |

| Note: This page limit includes the Additional Educational Information required for F30 and F31 applications. | 2 |

| (when applicable) | 1 |

5 |

For Individual Career Development Award (K, excluding K12) Applications

Including K01, K02, K05, K07, K08, K18, K22, K23, K24, K25, K26, K38, K43, K76, and K99/R00

| Section of Application | Page Limits* (Unless the funding opportunity specifies a different limit) |

|---|---|

| 30 lines of text | |

| Three sentences | |

| (when applicable) | 1 |

12 (for both attachments combined) | |

1 | |

1 | |

| (Include only when required by the specific NOFO, e.g., K24 and K05) | 6 |

6 | |

6 | |

1 | |

1 | |

5 |

For Institutional Training (T) , International Training ( D43 , D71 , U2R ), Institutional Career Development ( K12 , KL2 ), and Research Education ( R25 , UE5 , R38 , DP7 ) Applications

If no page limit is listed in the table below,in Section IV of the NOFO under Page Limitations, or in a related notice, you can assume the attachment does not have a limit.

| Section of Application | Page Limits* (Unless the funding opportunity specifies a different limit) |

|---|---|

| 30 lines of text | |

| Three sentences | |

| (when applicable) | 3 |

| (when applicable) | 1 |

| (Attachment 2 on PHS 398 Research Plan form; applies only to , , , and ) | 1 |

| (uploaded via the Research Strategy on PHS 398 Research Plan form) For , , , and applications only | 25 |

| (Attachment 2 on PHS 398 Research Training Program Plan form) For , , , , , and all only | 25 |

| (Attachment 3 on PHS 398 Research Training Program Plan form) For , , , , , and all only | 3 |

| (Attachment 4 on PHS 398 Research Training Program Plan form) For , , , , and all only | 3 |

| (for renewal applications) For D43, D71, U2R, K12, KL2, and all Training (T) only | 5 pages for a program overview and 1 page for each appointee to the grant |

5 |

For R01 , R03 , R21 , S10 , U01 , and all other Applications

Note: Not all application form sets include all the attachments listed below. For example, the S10 does not include the PHS Research Plan form so the Introduction, Specific Aims, and Research Strategy attachment page limits do not apply.

| Section of Application | Activity Codes | Page Limits* (Unless the funding opportunity specifies a different limit) |

|---|---|---|

| For all Activity Codes | 30 lines of text | |

| For all Activity Codes excluding C06, UC6, and G20. | three sentences | |

| For all Activity Codes (including each applicable component of a multi-component application) | 1 | |

| For all Activity Codes that use an application form with the Specific Aims section (including each component of a multi-component application) | 1 | |

| For Activity Code | 5 | |

For Activity Codes , , , , R16, , , , , , , , , , , X01 and X02 opportunities can be either 6 or 12 pages. Review the NOFO for details. R21 page limit may be different when combined with other activity codes. For example, R21/R33. | 6 | |

| For Activity Code | 10 | |

For Activity Codes , , , , , , , , , , , / , , , , , , , , / , , , , , , , , , , , , / , / , , , , , , , , , , X01 and X02 opportunities can be either 6 or 12 pages. Review the NOFO for details. | 12 | |

| For all other Activity Codes | Follow NOFO instructions | |

| For Activity Codes , , , , , (Attachment 7 on SBIR/STTR Information form) | 12 | |

| For all Activity Codes (including and which previously had special page limits) | 5 |

Microsoft Research Lab – Asia

Probts: unified benchmarking for time-series forecasting, share this page.

Author: Machine Learning Group

Time-series forecasting is crucial across various industries, including health, energy, commerce, climate, etc. Accurate forecasts over different prediction horizons are essential for both short-term and long-term planning needs across these domains. For instance, during a public health emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic, projections of infected cases and fatalities over one to four weeks are essential for allocating medical and societal resources effectively. In the energy sector, precise forecasts of electricity demand on an hourly, daily, weekly, and even monthly basis are crucial for power management and renewable energy scheduling. Logistics relies on forecasting short-term and long-term cargo volumes for adaptive route scheduling and efficient supply chain management.

Beyond covering various prediction horizons, accurate forecasting must extend beyond point estimates to include distributional forecasts that quantify estimation uncertainty. Both the expected estimates and the associated uncertainties are indispensable for subsequent planning and optimization, providing a comprehensive view that informs better decision-making.

Given the critical need for accurate point and distributional forecasting across diverse prediction horizons, researchers from Microsoft Research Asia revisited existing time-series forecasting studies to assess their effectiveness in meeting these essential demands. The review encompasses state-of-the-art models developed across various research threads:

- Classical time-series models : These models typically require training from scratch on each dataset, focusing on either long-term point forecasting (e.g., PatchTST, iTransformer) or short-term distributional forecasting (e.g., CSDI, TimeGrad).

- Recent time-series foundation models : These models involve universal pre-training across extensive datasets and are developed by both industrial labs (e.g., TimesFM, MOIRAI, Chronos) and academic institutions (e.g., Timer, UniTS).

Despite the advancements, researchers find that existing approaches often lack a holistic consideration of all essential forecasting needs. This limitation results in “biased” methodological designs and unverified performance in untested scenarios.

To address the gaps identified in existing time-series forecasting studies, researchers developed the ProbTS tool. ProbTS serves as a unified benchmarking platform designed to evaluate how well current approaches meet essential forecasting needs. By highlighting crucial methodological differences, ProbTS provides a comprehensive understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of advanced time-series models and unveils opportunities for future research and innovation.

Repo: https://github.com/microsoft/ProbTS (opens in new tab)

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.07446v4 (opens in new tab)

Paradigm differences: Methodological analysis of time series forecasting

The benchmark study using ProbTS highlights two crucial methodological differences found in contemporary research: the forecasting paradigms for point and distributional estimation, and the decoding schemes for variable-length forecasting across different horizons.

Forecasting paradigms for point and distributional estimation

- Point forecasting only: Approaches that support only point forecasting, providing expected estimates without uncertainty quantification.

- Predefined distribution heads: Methods that use predefined distribution heads to generate distributional forecasts, offering a fixed structure for uncertainty estimation.

- Neural distribution estimation modules: Techniques employing neural network-based modules to estimate distributions, allowing for more flexible and potentially more accurate uncertainty quantification.

Decoding schemes for variable-length forecasting across different horizons

- Autoregressive (AR) methods: These methods generate forecasts step-by-step, using previous predictions as inputs for future time steps. They are suitable for scenarios where sequential dependencies are crucial.

- Non-Autoregressive (NAR) methods: These methods produce forecasts for all time steps simultaneously, offering faster predictions and potentially better performance for long-term forecasting.

The research results under the ProbTS framework reveals several key insights:

Firstly, due to customized neural architectures, long-term point forecasting approaches excel in long-term scenarios but struggle in short-term cases and with complex data distributions. The lack of uncertainty quantification leads to significant performance gaps compared to probabilistic models when dealing with complex data distributions. Conversely, short-term probabilistic forecasting methods are proficient in short-term distributional forecasting but exhibit performance degradation and efficiency issues in long-term scenarios.

Secondly, regarding the characteristics of different decoding schemes, NAR decoding is predominantly used in long-term point forecasting models, while short-term probabilistic forecasting models do not show such a biased preference. Meanwhile, AR decoding suffers from error accumulation over extended horizons but may perform better with strong seasonal patterns.

Lastly, for current time-series foundation models, the limitations of AR decoding are reaffirmed in long-term forecasting. Additionally, foundation models show limited support for distributional forecasting, highlighting the need for improved modeling of complex data distributions.

Detailed results and analysis on classical time-series models

Researchers benchmark classical time-series models across a wide range of forecasting scenarios, encompassing both short and long prediction horizons. The evaluation includes both point forecasting metrics (Normalized Mean Absolute Error, NMAE) and distributional forecasting metrics (Continuous Ranked Probability Score, CRPS). Additionally, researchers calculate a non-Gaussianity score to quantify the complexity of data distribution for each forecasting scenario.

Based on the data presented in Figure 2, several noteworthy observations emerge:

- Limitations of long-term point forecasting models: Customized neural architectures for time-series, primarily designed for long-term point forecasting, excel in long-term scenarios. However, their architectural benefits significantly diminish in short-term cases (see Figure 2(a) and 2(c)). Furthermore, their inability to quantify forecasting uncertainty results in larger performance gaps compared to probabilistic models, especially when the data distribution is complex (see Figure 2(c) and 2(d)).

- Weaknesses of short-term probabilistic forecasting models: Current probabilistic forecasting models, while proficient in short-term distributional forecasting, face challenges in long-term scenarios, as evidenced by significant performance degradations (see Figure 2(a) and 2(b)). In addition to unsatisfactory performance, some models experience severe efficiency issues as the prediction horizon increases.

These observations yield several important implications. Firstly, effective architecture designs for short-term forecasting remain elusive and warrant further research. Secondly, the ability to characterize complex data distributions is crucial, as long-term distributional forecasting presents significant challenges in both performance and efficiency.

Following that, researchers compare Autoregressive (AR) and Non-Autoregressive (NAR) decoding schemes across various forecasting scenarios, highlighting their respective pros and cons in relation to forecasting horizons, trend strength, and seasonality strength.

Researchers find that nearly all long-term point forecasting models use the NAR decoding scheme for multi-step outputs, whereas probabilistic forecasting models exhibit a more balanced use of AR and NAR schemes. Researchers aim to elucidate this disparity and highlight the pros and cons of each scheme, as shown in Figure 3.

- Error accumulation in AR decoding: Figure 3(a) shows that existing AR models experiences a larger performance gap compared to NAR methods as the prediction horizon increases, suggesting that AR may suffer from error accumulation.

- Impact of trend strength: Figure 3(b) connects the performance gap with trend strength, indicating that strong trending effects can lead to significant performance differences between NAR and AR models. However, there are exceptions where strong trends do not cause substantial performance degradation in AR-based models.

- Impact of seasonality strength: Figure 3(c) explains these exceptions by introducing seasonality strength as a factor. Surprisingly, AR-based models perform better in scenarios with strong seasonal patterns, likely due to their parameter efficiency in such contexts.

- Combined effects of trend and seasonality: Figure 3(d) demonstrates the combined effects of trend and seasonality on performance differences.

Based on these analyses, researchers point out that the choice between AR and NAR decoding schemes in different research branches is primarily driven by the specific data characteristics in their focused forecasting scenarios. This explains the preference for the NAR decoding paradigm in most long-term forecasting models. However, this preference for NAR may overlook the advantages of AR, particularly its effectiveness in handling strong seasonality. Since both NAR and AR have their own strengths and weaknesses, future research should aim for a more balanced exploration, leveraging their unique advantages and addressing their limitations.

Detailed results and analysis on time-series foundation models

Researchers then extend the analysis framework to include recent time-series foundation models and examine their distributional forecasting capabilities.

The results show that:

- AR vs. NAR decoding in long-term forecasting: Figure 4(a) reaffirms the limitations of AR decoding over extended forecasting horizons. This suggests that time-series data, due to its continuous nature, may require special adaptations beyond those used in language modeling (which operates in a discrete space). Additionally, it is confirmed that AR-based and NAR-based models can deliver comparable performance in short-term scenarios, with AR-based models occasionally outperforming their NAR counterparts.

- Distributional forecasting capabilities: Figure 4(b) compares the distributional forecasting capabilities of foundation models with CSDI, underscoring the importance of capturing complex data distributions. Current foundation models demonstrate limited support for distributional forecasting, typically using predefined distribution heads (e.g., MOIRAI) or approximated distribution modeling in a value-quantized space (e.g., Chronos).

These observations lead to several important conclusions: While AR-based models can be effective in short-term scenarios, their performance diminishes over longer horizons, highlighting the need for further refinement. Time-series data may require unique treatments to optimize AR decoding, particularly for long-term forecasting. The ability to accurately model complex data distributions remains a critical area for improvement in time-series foundation models.

Future directions: Evolving perspectives, models, and tools

Based on the evaluation and analysis of existing methods, researchers have proposed several important future directions for time series prediction models. These directions, if pursued, could significantly impact key scenarios across various industry sectors.

Future direction 1: Adopting a comprehensive perspective of forecasting demands. One primary future direction is to adopt a holistic perspective of essential forecasting demands when developing new models. This approach can help rethink the methodological choices of different models, understand their strengths and weaknesses, and foster more diverse research explorations.

Future direction 2: Designing a universal model. A fundamental question raised by these results is whether we can develop a universal model that fulfills all essential forecasting demands or if we should treat different forecasting demands separately, introducing specific techniques for each. While it is challenging to provide a definitive answer, the ultimate goal could be to create a universal model. When developing such a model, it is necessary to consider issues such as input representation, encoding architecture, decoding scheme, and distribution estimation module, etc. Additionally, future research is needed to address the challenge of distributional forecasting in high-dimensional and noisy scenarios, particularly for long horizons, and to leverage the advantages of both AR and NAR decoding schemes while avoiding their weaknesses.

Future direction 3: Developing tools for future research. To support future research in these directions, researchers have made the ProbTS tool publicly available, hoping this tool will facilitate advancements in the field and encourage collective efforts from the research community.

By addressing these future directions, researchers aim to push the boundaries of time-series forecasting, ultimately developing models that are more robust, versatile, and capable of handling a wide range of forecasting challenges. This progress holds the potential to significantly impact numerous industries, leading to better decision-making, optimized operations, and improved outcomes across critical sectors.

- Follow on X

- Like on Facebook

- Follow on LinkedIn

- Subscribe on Youtube

- Follow on Instagram

- Subscribe to our RSS feed

Share this page:

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit

- Management Team

- Working Groups

- Leadership Partners & Associate Members

- Pre-Clinical Courses

- Physician Associate Program

- Physician Assistant Online Program

- Yale School of Nursing

- Yale School of Public Health

- FAQs on Pronoun Use

- Faculty & Staff

- Students & Trainees

- News & Events

- Our Members

- Defending Gender-Affirming Care in Alabama

- Flawed Medicaid Report in Florida

- Biased Science in Texas & Alabama

- Healthcare Program Project

- Yale Clinics & Programs

- Organizations with LGBTQI Health Resources

- LGBTQI+ and Diversity Groups at Yale

- Health Professional Community

- Connecticut State Community

- Regional and National Community

INFORMATION FOR

- Residents & Fellows

- Researchers

Participate in Research: New Resource for Families and Practitioners

A new webpage has been launched at the Yale Child Study Center (YCSC) to allow families and referring practitioners – and soon school-based personnel – to view and access research participation opportunities at the center. Details including brief study descriptions, eligibility criteria, applicable compensation, and contact information are provided across nearly 30 studies, with more to be added soon.

YCSC research teams collaborate with youth, families, schools, and communities to improve overall social, emotional, behavioral, and developmental health. Visit the new website to learn more about the current and ongoing research efforts underway and find out how to participate in – or refer potential participants to – clinical or school-based studies. A “ Frequently Asked Questions ” page is also available, addressing some general questions related to research participation, including the voluntary nature of all study participation.

The YCSC, which serves as the department of child psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine, is actively growing in many areas – from basic research in childhood psychiatric disorders to applied research with youth, schools, and families to advance social, emotional, and academic outcomes. There are also research efforts underway related to training clinicians and other behavioral health professionals in evidence-based mental health services, as well as in training educators and school-based practitioners in evidence-based social and emotional instruction.

Please enable JavaScript in your web browser to get the best experience.

We use cookies to track usage and preferences.

Primary navigation

- PhD students

- Exhibitions

- Translation

- Work experience

Research reveals impact of gut microbiome on hormone levels in mice

- Date created: 26 September 2024

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Email

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute have shown that the balance of bacteria in the gut can influence symptoms of hypopituitarism in mice.

They also showed that aspirin was able to improve hormone deficiency symptoms in mice with this condition.

Christophe Galichet and Robin Lovell-Badge were researching mouse Sox3 mutations, which cause hypopituitarism in mice and humans, at the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR). When they transferred mice with Sox3 mutations from the NIMR to the Crick, they made an unexpected discovery.

People with mutations in a gene called Sox3 develop hypopituitarism, where the pituitary gland doesn’t make enough hormones. It can result in growth problems, infertility and poor responses of the body to stress.

In research published today in PLOS Genetics , the scientists at the Crick removed Sox3 from mice, causing them to develop hypopituitarism around the time of weaning (starting to eat solid food).

They found that mutations in Sox3 largely affect the hypothalamus in the brain, which instructs the pituitary gland to release hormones. However, the gene is normally active in several brain cell types, so the first task was to ask which specific cells were most affected by its absence.

The scientists observed a reduced number of cells called NG2 glia, suggesting that these play a critical role in inducing the pituitary gland cells to mature around weaning, which was not known previously. This could explain the associated impact on hormone production.

The team then treated the mice with a low dose of aspirin for 21 days. This caused the number of NG2 glia in the hypothalamus to increase and reversed the symptoms of hypopituitarism in the mice.

NG2 glia (red) in the median eminence, which connects the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, are reduced in the mice with Sox3 mutations (right-hand panel).

Although it’s not yet clear how aspirin had this effect, the findings suggest that it could be explored as a potential treatment for people with Sox3 mutations or other situations where the NG2 glia are compromised.

It was a huge surprise to find that changes in the gut microbiome reversed hypopituitarism in the mice without Sox3. Christophe Galichet

An incidental discovery revealed the role of gut bacteria in hormone production

When the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) merged with the Crick in 2015, mouse embryos were transferred from the former building to the latter, and this included the mice with Sox3 mutations.

When these mice reached the weaning stage at the Crick, the researchers were surprised to find that they no longer had the expected hormonal deficiencies.

After exploring a number of possible causes, lead author Christophe Galichet compared the microbiome – bacteria, fungi and viruses that live in the gut – in the mice from the Crick and mice from the NIMR, observing several differences in its makeup and diversity. This could have been due to the change in diet, water environment, or other factors that accompanied the relocation.

He also examined the number of NG2 glia in the Crick mice, finding that these were also at normal levels, suggesting that the Crick-fed microbiome was somehow protective against hypopituitarism.

To confirm this theory, Christophe transplanted faecal matter retained from NIMR mice into Crick mice, observing that the Crick mice once again showed symptoms of hypopituitarism and had lower numbers of NG2 glia.

Although the exact mechanism is unknown, the scientists conclude that the make-up of the gut microbiome is an example of an important environmental factor having a significant influence on the consequences of a genetic mutation, in this case influencing the function of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland.

Christophe Galichet , former Senior Laboratory Research Scientist at the Crick and now Research Operations Manager at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre , said: “It was a huge surprise to find that changes in the gut microbiome reversed hypopituitarism in the mice without Sox3 . It’s reinforced to me how important it is to be aware of all variable factors, including the microbiome, when working with animals in research and how nurture can influence nature.”