- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 24 October 2019

A scoping review of the literature on the current mental health status of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America

- Mara Mihailescu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6878-1024 1 &

- Elena Neiterman 2

BMC Public Health volume 19 , Article number: 1363 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

70 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

This scoping review summarizes the existing literature regarding the mental health of physicians and physicians-in-training and explores what types of mental health concerns are discussed in the literature, what is their prevalence among physicians, what are the causes of mental health concerns in physicians, what effects mental health concerns have on physicians and their patients, what interventions can be used to address them, and what are the barriers to seeking and providing care for physicians. This review aims to improve the understanding of physicians’ mental health, identify gaps in research, and propose evidence-based solutions.

A scoping review of the literature was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, which examined peer-reviewed articles published in English during 2008–2018 with a focus on North America. Data were summarized quantitatively and thematically.

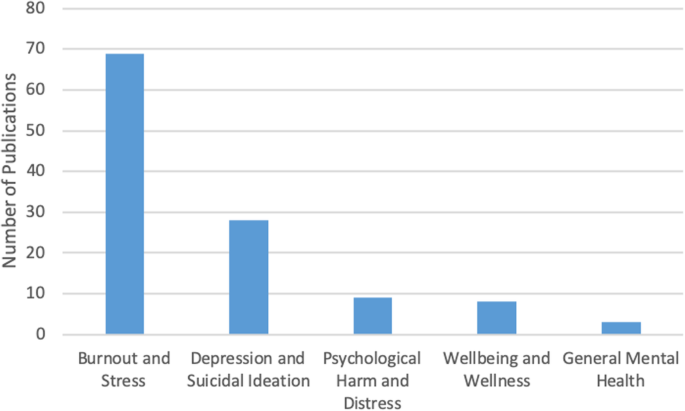

A total of 91 articles meeting eligibility criteria were reviewed. Most of the literature was specific to burnout ( n = 69), followed by depression and suicidal ideation ( n = 28), psychological harm and distress ( n = 9), wellbeing and wellness ( n = 8), and general mental health ( n = 3). The literature had a strong focus on interventions, but had less to say about barriers for seeking help and the effects of mental health concerns among physicians on patient care.

Conclusions

More research is needed to examine a broader variety of mental health concerns in physicians and to explore barriers to seeking care. The implication of poor physician mental health on patients should also be examined more closely. Finally, the reviewed literature lacks intersectional and longitudinal studies, as well as evaluations of interventions offered to improve mental wellbeing of physicians.

Peer Review reports

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.” [ 41 ] One in four people worldwide are affected by mental health concerns [ 40 ]. Physicians are particularly vulnerable to experiencing mental illness due to the nature of their work, which is often stressful and characterized by shift work, irregular work hours, and a high pressure environment [ 1 , 21 , 31 ]. In North America, many physicians work in private practices with no access to formal institutional supports, which can result in higher instances of social isolation [ 13 , 27 ]. The literature on physicians’ mental health is growing, partly due to general concerns about mental wellbeing of health care workers and partly due to recognition that health care workers globally are dissatisfied with their work, which results in burnout and attrition from the workforce [ 31 , 34 ]. As a consequence, more efforts have been made globally to improve physicians’ mental health and wellness, which is known as “The Quadruple Aim.” [ 34 ] While the literature on mental health is flourishing, however, it has not been systematically summarized. This makes it challenging to identify what is being done to improve physicians’ wellbeing and which solutions are particularly promising [ 7 , 31 , 33 , 37 , 38 ]. The goal of our paper is to address this gap.

This paper explores what is known from the existing peer-reviewed literature about the mental health status of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America. Specifically, we examine (1) what types of mental health concerns among physicians are commonly discussed in the literature; (2) what are the reported causes of mental health concerns in physicians; (3) what are the effects that mental health concerns may have on physicians and their patients; (4) what solutions are proposed to improve mental health of physicians; and (5) what are the barriers to seeking and providing care to physicians with mental health concerns. Conducting this scoping review, our goal is to summarize the existing research, identifying the need for a subsequent systematic review of the literature in one or more areas under the study. We also hope to identify evidence-based interventions that can be utilized to improve physicians’ mental wellbeing and to suggest directions for future research [ 2 ]. Evidence-based interventions might have a positive impact on physicians and improve the quality of patient care they provide.

A scoping review of the academic literature on the mental health of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 2 ] methodological framework. Our review objectives and broad focus, including the general questions posed to conduct the review, lend themselves to a scoping review approach, which is suitable for the analysis of a broader range of study designs and methodologies [ 2 ]. Our goal was to map the existing research on this topic and identify knowledge gaps, without making any prior assumptions about the literature’s scope, range, and key findings [ 29 ].

Stage 1: identify the research question

Following the guidelines for scoping reviews [ 2 ], we developed a broad research question for our literature search, asking what does the academic literature tell about mental health issues among physicians, residents, and medical students in North America ? Burnout and other mental health concerns often begin in medical training and continue to worsen throughout the years of practice [ 31 ]. Recognizing that the study and practice of medicine plays a role in the emergence of mental health concerns, we focus on practicing physicians – general practitioners, specialists, and surgeons – and those who are still in training – residents and medical students. We narrowed down the focus of inquiry by asking the following sub-questions:

What types of mental health concerns among physicians are commonly discussed in the literature?

What are the reported causes of mental health problems in physicians and what solutions are available to improve the mental wellbeing of physicians?

What are the barriers to seeking and providing care to physicians suffering from mental health problems?

Stage 2: identify the relevant studies

We included in our review empirical papers published during January 2008–January 2018 in peer-reviewed journals. Our exclusive focus on peer-reviewed and empirical literature reflected our goal to develop an evidence-based platform for understanding mental health concerns in physicians. Since our focus was on prevalence of mental health concerns and promising practices available to physicians in North America, we excluded articles that were more than 10 years old, suspecting that they might be too outdated for our research interest. We also excluded papers that were not in English or outside the region of interest. Using combinations of keywords developed in consultation with a professional librarian (See Table 1 ), we searched databases PUBMed, SCOPUS, CINAHL, and PsychNET. We also screened reference lists of the papers that came up in our original search to ensure that we did not miss any relevant literature.

Stage 3: literature selection

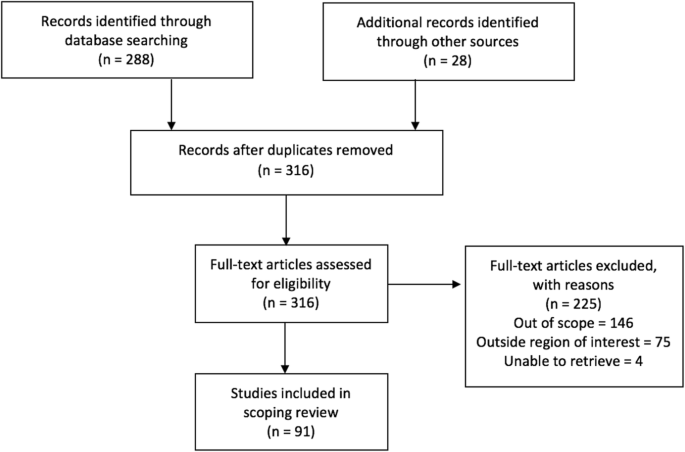

Publications were imported into a reference manager and screened for eligibility. During initial abstract screening, 146 records were excluded for being out of scope, 75 records were excluded for being outside the region of interest, and 4 papers were excluded because they could not be retrieved. The remaining 91 papers were included into the review. Figure 1 summarizes the literature search and selection.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Stage 4: charting the data

A literature extraction tool was created in Microsoft Excel to record the author, date of publication, location, level of training, type of article (empirical, report, commentary), and topic. Both authors coded the data inductively, first independently reading five articles and generating themes from the data, then discussing our coding and developing a coding scheme that was subsequently applied to ten more papers. We then refined and finalized the coding scheme and used it to code the rest of the data. When faced with disagreements on narrowing down the themes, we discussed our reasoning and reached consensus.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The data was summarized by frequency and type of publication, mental health topics, and level of training. The themes inductively derived from the data included (1) description of mental health concerns affecting physicians and physicians-in-training; (2) prevalence of mental health concerns among this population; (3) possible causes that can explain the emergence of mental health concerns; (4) solutions or interventions proposed to address mental health concerns; (5) effects of mental health concerns on physicians and on patient outcomes; and (6) barriers for seeking and providing help to physicians afflicted with mental health concerns. Each paper was coded based on its relevance to major theme(s) and, if warranted, secondary focus. Therefore, one paper could have been coded in more than one category. Upon analysis, we identified the gaps in the literature.

Characteristics of included literature

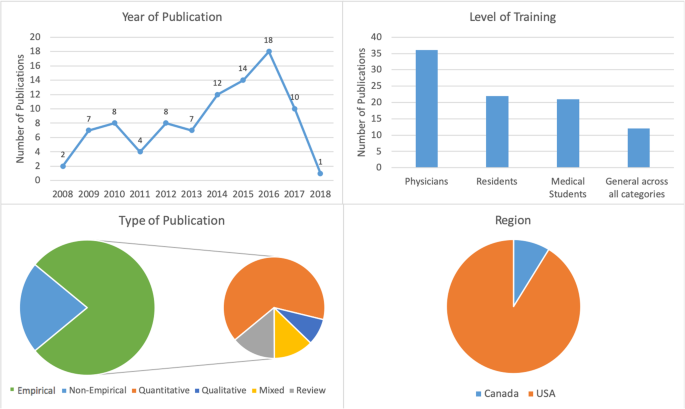

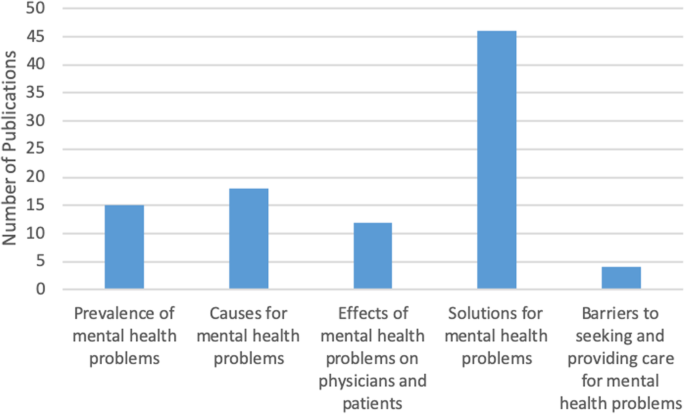

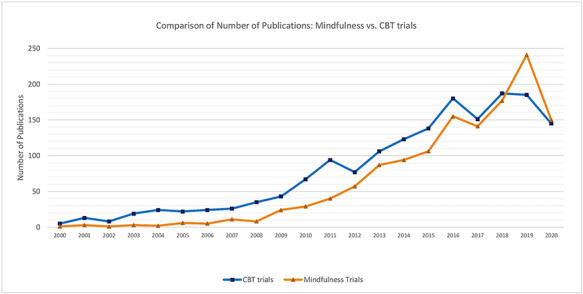

The initial search yielded 316 records of which 91 publications underwent full-text review and were included in our scoping review. Our analysis revealed that the publications appear to follow a trend of increase over the course of the last decade reflecting the growing interest in physicians’ mental health. More than half of the literature was published in the last 4 years included in the review, from 2014 to 2018 ( n = 55), with most publications in 2016 ( n = 18) (Fig. 2 ). The majority of papers ( n = 36) focused on practicing physicians, followed by papers on residents ( n = 22), medical students ( n = 21), and those discussing medical professionals with different level of training ( n = 12). The types of publications were mostly empirical ( n = 71), of which 46 papers were quantitative. Furthermore, the vast majority of papers focused on the United States of America (USA) ( n = 83), with less than 9% focusing on Canada ( n = 8). The frequency of identified themes in the literature is broken down into prevalence of mental health concerns ( n = 15), causes of mental health concerns ( n = 18), effects of mental health concerns on physicians and patients ( n = 12), solutions and interventions for mental health concerns ( n = 46), and barriers to seeking and providing care for mental health concerns ( n = 4) (Fig. 3 ).

Number of sources by characteristics of included literature

Frequency of themes in literature ( n = 91)

Mental health concerns and their prevalence in the literature

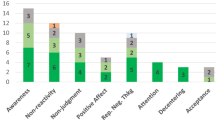

In this thematic category ( n = 15), we coded the papers discussing the prevalence of specific mental health concerns among physicians and those comparing physicians’ mental health to that of the general population. Most papers focused on burnout and stress ( n = 69), which was followed by depression and suicidal ideation ( n = 28), psychological harm and distress ( n = 9), wellbeing and wellness ( n = 8), and general mental health ( n = 3) (Fig. 4 ). The literature also identified that, on average, burnout and mental health concerns affect 30–60% of all physicians and residents [ 4 , 5 , 8 , 9 , 15 , 25 , 26 ].

Number of sources by mental health topic discussed ( n = 91)

There was some overlap between the papers discussing burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation, suggesting that work-related stress may lead to the emergence of more serious mental health problems [ 3 , 12 , 21 ], as well as addiction and substance abuse [ 22 , 27 ]. Residency training was shown to produce the highest rates of burnout [ 4 , 8 , 19 ].

Causes of mental health concerns

Papers discussing the causes of mental health concerns in physicians formed the second largest thematic category ( n = 18). Unbalanced schedules and increasing administrative work were defined as key factors in producing poor mental health among physicians [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 13 , 15 , 27 ]. Some papers also suggested that the nature of the medical profession itself – competitive culture and prioritizing others – can lead to the emergence of mental health concerns [ 23 , 27 ]. Indeed, focus on qualities such as rigidity, perfectionism, and excessive devotion to work during the admission into medical programs fosters the selection of students who may be particularly vulnerable to mental illness in the future [ 21 , 24 ]. The third cluster of factors affecting mental health stemmed from structural issues, such as pressure from the government and insurance, fragmentation of care, and budget cuts [ 13 , 15 , 18 ]. Work overload, lack of control over work environment, lack of balance between effort and reward, poor sense of community among staff, lack of fairness and transparency by decision makers, and dissonance between one’s personal values and work tasks are the key causes for mental health concerns among physicians [ 20 ]. Govardhan et al. conceptualized causes for mental illness as having a cyclical nature - depression leads to burnout and depersonalization, which leads to patient dissatisfaction, causing job dissatisfaction and more depression [ 19 ].

Effects of mental health concerns on physicians and patients

A relatively small proportion of papers (13%) discussed the effects of mental health concerns on physicians and patients. The literature prioritized the direct effect of mental health on physicians ( n = 11) with only one paper focusing solely on the indirect effects physicians’ mental health may have on patients. Poor mental health in physicians was linked to decreased mental and physical health [ 3 , 14 , 15 ]. In addition, mental health concerns in physicians were associated with reduction in work hours and the number of patients seen, decrease in job satisfaction, early retirement, and problems in personal life [ 3 , 5 , 15 ]. Lu et al. found that poor mental health in physicians may result in increased medical errors and the provision of suboptimal care [ 25 ]. Thus physicians’ mental wellbeing is linked to the quality of care provided to patients [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 10 , 17 ].

Solutions and interventions

In this largest thematic category ( n = 46) we coded the literature that offered solutions for improving mental health among physicians. We identified four major levels of interventions suggested in the literature. A sizeable proportion of literature discussed the interventions that can be broadly categorized as primary prevention of mental illness. These papers proposed to increase awareness of physicians’ mental health and to develop strategies that can help to prevent burnout from occurring in the first place [ 4 , 12 ]. Some literature also suggested programs that can help to increase resilience among physicians to withstand stress and burnout [ 9 , 20 , 27 ]. We considered the papers referring to the strategies targeting physicians currently suffering from poor mental health as tertiary prevention . This literature offered insights about mindfulness-based training and similar wellness programs that can increase self-awareness [ 16 , 18 , 27 ], as well as programs aiming to improve mental wellbeing by focusing on physical health [ 17 ].

While the aforementioned interventions target individual physicians, some literature proposed workplace/institutional interventions with primary focus on changing workplace policies and organizational culture [ 4 , 13 , 23 , 25 ]. Reducing hours spent at work and paperwork demands or developing guidelines for how long each patient is seen have been identified by some researchers as useful strategies for improving mental health [ 6 , 11 , 17 ]. Offering access to mental health services outside of one’s place of employment or training could reduce the fear of stigmatization at the workplace [ 5 , 12 ]. The proposals for cultural shift in medicine were mainly focused on promoting a less competitive culture, changing power dynamics between physicians and physicians-in-training, and improving wellbeing among medical students and residents. The literature also proposed that the medical profession needs to put more emphasis on supporting trainees, eliminating harassment, and building strong leadership [ 23 ]. Changing curriculum for medical students was considered a necessary step for the cultural shift [ 20 ]. Finally, while we only reviewed one paper that directly dealt with the governmental level of prevention, we felt that it necessitated its own sub-thematic category because it identified the link between government policy, such as health care reforms and budget cuts, and the services and care physicians can provide to their patients [ 13 ].

Barriers to seeking and providing care

Only four papers were summarized in this thematic category that explored what the literature says about barriers for seeking and providing care for physicians suffering from mental health concerns. Based on our analysis, we identified two levels of factors that can impact access to mental health care among physicians and physicians-in-training.

Individual level barriers stem from intrinsic barriers that individual physicians may experience, such as minimizing the illness [ 21 ], refusing to seek help or take part in wellness programs [ 14 ], and promoting the culture of stoicism [ 27 ] among physicians. Another barrier is stigma associated with having a mental illness. Although stigma might be experienced personally, literature suggests that acknowledging the existence of mental health concerns may have negative consequences for physicians, including loss of medical license, hospital privileges, or professional advancement [ 10 , 21 , 27 ].

Structural barriers refer to the lack of formal support for mental wellbeing [ 3 ], poor access to counselling [ 6 ], lack of promotion of available wellness programs [ 10 ], and cost of treatment. Lack of research that tests the efficacy of programs and interventions aiming to improve mental health of physicians makes it challenging to develop evidence-based programs that can be implemented at a wider scale [ 5 , 11 , 12 , 18 , 20 ].

Our analysis of the existing literature on mental health concerns in physicians and physicians-in-training in North America generated five thematic categories. Over half of the reviewed papers focused on proposing solutions, but only a few described programs that were empirically tested and proven to work. Less common were papers discussing causes for deterioration of mental health in physicians (20%) and prevalence of mental illness (16%). The literature on the effects of mental health concerns on physicians and patients (13%) focused predominantly on physicians with only a few linking physicians’ poor mental health to medical errors and decreased patient satisfaction [ 3 , 4 , 16 , 24 ]. We found that the focus on barriers for seeking and receiving help for mental health concerns (4%) was least prevalent. The topic of burnout dominated the literature (76%). It seems that the nature of physicians’ work fosters the environment that causes poor mental health [ 1 , 21 , 31 ].

While emphasis on burnout is certainly warranted, it might take away the attention paid to other mental health concerns that carry more stigma, such as depression or anxiety. Establishing a more explicit focus on other mental health concerns might promote awareness of these problems in physicians and reduce the fear such diagnosis may have for doctors’ job security [ 10 ]. On the other hand, utilizing the popularity and non-stigmatizing image of “burnout” might be instrumental in developing interventions promoting mental wellbeing among a broad range of physicians and physicians-in-training.

Table 2 summarizes the key findings from the reviewed literature that are important for our understanding of physician mental health. In order to explicitly summarize the gaps in the literature, we mapped them alongside the areas that have been relatively well studied. We found that although non-empirical papers discussed physicians’ mental wellbeing broadly, most empirical papers focused on medical specialty (e.g. neurosurgeons, family medicine, etc.) [ 4 , 8 , 15 , 19 , 25 , 28 , 35 , 36 ]. Exclusive focus on professional specialty is justified if it features a unique context for generation of mental health concerns, but it limits the ability to generalize the findings to a broader population of physicians. Also, while some papers examined the impact of gender on mental health [ 7 , 32 , 39 ], only one paper considered ethnicity as a potential factor for mental health concerns and found no association [ 4 ]. Given that mental health in the general population varies by gender, ethnicity, age, and sexual orientation, it would be prudent to examine mental health among physicians using an intersectional analysis [ 30 , 32 , 39 ]. Finally, of the empirical studies we reviewed, all but one had a cross-sectional design. Longitudinal design might offer a better understanding of the emergence and development of mental health concerns in physicians and tailor interventions to different stages of professional career. Additionally, it could provide an opportunity to evaluate programs’ and policies’ effectiveness in improving physicians’ mental health. This would also help to address the gap that we identified in the literature – an overarching focus on proposing solutions with little demonstrated evidence they actually work.

This review has several limitations. First, our focus on academic literature may have resulted in overlooking the papers that are not peer-reviewed but may provide interesting solutions to physician mental health concerns. It is possible that grey literature – reports and analyses published by government and professional organizations – offers possible solutions that we did not include in our analysis or offers a different view on physicians’ mental health. Additionally, older papers and papers not published in English may have information or interesting solutions that we did not include in our review. Second, although our findings suggest that the theme of burnout dominated the literature, this may be the result of the search criteria we employed. Third, following the scoping review methodology [ 2 ], we did not assess the quality of the papers, focusing instead on the overview of the literature. Finally, our research was restricted to North America, specifically Canada and the USA. We excluded Mexico because we believed that compared to the context of medical practice in Canada and the USA, which have some similarities, the work experiences of Mexican physicians might be different and the proposed solutions might not be readily applicable to the context of practice in Canada and the USA. However, it is important to note that differences in organization of medical practice in Canada and the USA do exist, as do differences across and within provinces in Canada and the USA. A comparative analysis can shed light on how the structure and organization of medical practice shapes the emergence of mental health concerns.

The scoping review we conducted contributes to the existing research on mental wellbeing of American and Canadian physicians by summarizing key knowledge areas and identifying key gaps and directions for future research. While the papers reviewed in our analysis focused on North America, we believe that they might be applicable to the global medical workforce. Identifying key gaps in our knowledge, we are calling for further research on these topics, including examination of medical training curricula and its impact on mental wellbeing of medical students and residents, research on common mental health concerns such as depression or anxiety, studies utilizing intersectional and longitudinal approaches, and program evaluations assessing the effectiveness of interventions aiming to improve mental wellbeing of physicians. Focus on the effect physicians’ mental health may have on the quality of care provided to patients might facilitate support from government and policy makers. We believe that large-scale interventions that are proven to work effectively can utilize an upstream approach for improving the mental health of physicians and physicians-in-training.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

United States of America

World Health Organization

Ahmed N, Devitt KS, Keshet I, Spicer J, Imrie K, Feldman L, et al. A systematic review of the effects of resident duty hour restrictions in surgery: impact on resident wellness, training, and patient outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):1041–53.

Article Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Atallah F, McCalla S, Karakash S, Minkoff H. Please put on your own oxygen mask before assisting others: a call to arms to battle burnout. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):731.e1.

Baer TE, Feraco AM, Tuysuzoglu Sagalowsky S, Williams D, Litman HJ, Vinci RJ. Pediatric resident burnout and attitudes toward patients. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20162163. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2163 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Blais R, Safianyk C, Magnan A, Lapierre A. Physician, heal thyself: survey of users of the Quebec physicians health program. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(10):e383–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brennan J, McGrady A. Designing and implementing a resiliency program for family medicine residents. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(1):104–14.

Cass I, Duska LR, Blank SV, Cheng G, NC dP, Frederick PJ, et al. Stress and burnout among gynecologic oncologists: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology Evidence-based Review and Recommendations. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(2):421–7.

Chan AM, Cuevas ST, Jenkins J 2nd. Burnout among osteopathic residents: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2016;116(2):100–5.

Chaukos D, Chad-Friedman E, Mehta DH, Byerly L, Celik A, McCoy TH Jr, et al. Risk and resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):189–94.

Compton MT, Frank E. Mental health concerns among Canadian physicians: results from the 2007-2008 Canadian physician health study. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(5):542–7.

Cunningham C, Preventing MD. Burnout. Trustee. 2016;69(2):6–7 1.

PubMed Google Scholar

Daskivich TJ, Jardine DA, Tseng J, Correa R, Stagg BC, Jacob KM, et al. Promotion of wellness and mental health awareness among physicians in training: perspective of a national, multispecialty panel of residents and fellows. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):143–7.

Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: a potential threat to successful health care reform. JAMA. 2011;305(19):2009–10.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Epstein RM, Krasner MS. Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):301–3.

Evans RW, Ghosh K. A survey of headache medicine specialists on career satisfaction and burnout. Headache. 2015;55(10):1448–57.

Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, Sharek PJ, Lewin D, Chiang VW, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):488–91.

Fargen KM, Spiotta AM, Turner RD, Patel S. The importance of exercise in the well-rounded physician: dialogue for the inclusion of a physical fitness program in neurosurgery resident training. World Neurosurg. 2016;90:380–4.

Gabel S. Demoralization in Health Professional Practice: Development, Amelioration, and Implications for Continuing Education. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2013 Spring. 2013;33(2):118–26.

Google Scholar

Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389–95.

Jennings ML, Slavin SJ. Resident wellness matters: optimizing resident education and wellness through the learning environment. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1246–50.

Keller EJ. Philosophy in medical education: a means of protecting mental health. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(4):409–13.

Krall EJ, Niazi SK, Miller MM. The status of physician health programs in Wisconsin and north central states: a look at statewide and health systems programs. WMJ. 2012;111(5):220–7.

Lemaire JB, Wallace JE. Burnout among doctors. BMJ. 2017;358:j3360.

Linzer M, Bitton A, Tu SP, Plews-Ogan M, Horowitz KR, Schwartz MD, et al. The end of the 15-20 minute primary care visit. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1584–6.

Lu DW, Dresden S, McCloskey C, Branzetti J, Gisondi MA. Impact of burnout on self-reported patient care among emergency physicians. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(7):996–1001.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422.

McClafferty H, Brown OW. Section on integrative medicine, committee on practice and ambulatory medicine, section on integrative medicine. Physician health and wellness. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):830–5.

Miyasaki JM, Rheaume C, Gulya L, Ellenstein A, Schwarz HB, Vidic TR, et al. Qualitative study of burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurologists in 2016. Neurology. 2017;89(16):1730–8.

Peterson J, Pearce P, Ferguson LA, Langford C. Understanding scoping reviews: definition, purpose, and process. JAANP. 2016;29:12–6.

Przedworski JM, Dovidio JF, Hardeman RR, Phelan SM, Burke SE, Ruben MA, et al. A comparison of the mental health and well-being of sexual minority and heterosexual first-year medical students: a report from the medical student CHANGE study. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):652–9.

Ripp JA, Privitera MR, West CP, Leiter R, Logio L, Shapiro J, et al. Well-being in graduate medical education: a call for action. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):914–7.

Salles A, Mueller CM, Cohen GL. Exploring the relationship between stereotype perception and Residents’ well-being. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(1):52–8.

Shiralkar MT, Harris TB, Eddins-Folensbee FF, Coverdale JH. A systematic review of stress-management programs for medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):158–64.

Sikka R, Morath J, Leape L. The quadruple aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(10):608–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160 .

Tawfik DS, Phibbs CS, Sexton JB, Kan P, Sharek PJ, Nisbet CC, et al. Factors Associated With Provider Burnout in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):608. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-4134 Epub 2017 Apr 18.

Turner TB, Dilley SE, Smith HJ, Huh WK, Modesitt SC, Rose SL, et al. The impact of physician burnout on clinical and academic productivity of gynecologic oncologists: a decision analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(3):642–6.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272.

Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47–54.

Woodside JR, Miller MN, Floyd MR, McGowen KR, Pfortmiller DT. Observations on burnout in family medicine and psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):13–9.

World Health Organization. (2001). Mental disorders affect one in four people.

World Health Organization. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice (Summary Report). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Not Applicable

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa, 55 Laurier Ave E, Ottawa, ON, K1N 6N5, Canada

Mara Mihailescu

School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON, N2L 3G1, Canada

Elena Neiterman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.M. and E.N. were involved in identifying the relevant research question and developing the combinations of keywords used in consultation with a professional librarian. M.M. performed the literature selection and screening of references for eligibility. Both authors were involved in the creation of the literature extraction tool in Excel. Both authors coded the data inductively, first independently reading five articles and generating themes from the data, then discussing their coding and developing a coding scheme that was subsequently applied to ten more papers. Both authors then refined and finalized the coding scheme and M.M. used it to code the rest of the data. M.M. conceptualized and wrote the first copy of the manuscript, followed by extensive drafting by both authors. E.N. was a contributor to writing the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mara Mihailescu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mihailescu, M., Neiterman, E. A scoping review of the literature on the current mental health status of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America. BMC Public Health 19 , 1363 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7661-9

Download citation

Received : 29 April 2019

Accepted : 20 September 2019

Published : 24 October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7661-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Mental illness

- Medical students

- Scoping review

- Interventions

- North America

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 20 August 2024

Examining the mental health services among people with mental disorders: a literature review

- Yunqi Gao 1 ,

- Richard Burns 1 ,

- Liana Leach 1 ,

- Miranda R. Chilver 1 &

- Peter Butterworth 2 , 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 24 , Article number: 568 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1188 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Mental disorders are a significant contributor to disease burden. However, there is a large treatment gap for common mental disorders worldwide. This systematic review summarizes the factors associated with mental health service use.

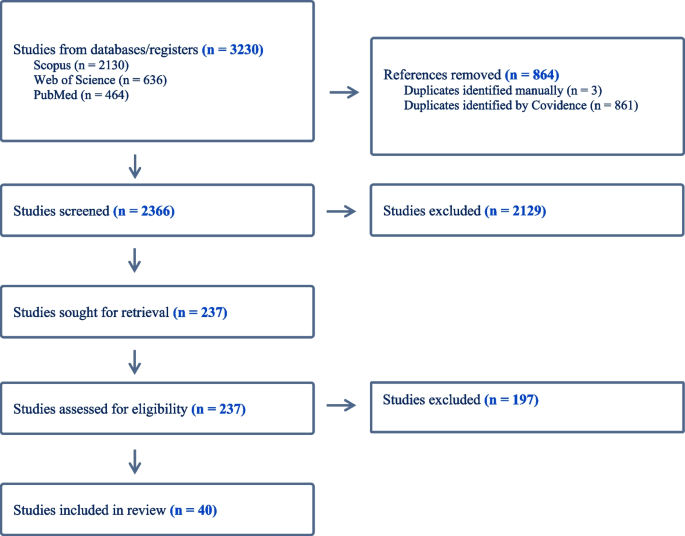

PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of Science were searched for articles describing the predictors of and barriers to mental health service use among people with mental disorders from January 2012 to August 2023. The initial search yielded 3230 articles, 2366 remained after removing duplicates, and 237 studies remained after the title and abstract screening. In total, 40 studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Middle-aged participants, females, Caucasian ethnicity, and higher household income were more likely to access mental health services. The use of services was also associated with the severity of mental symptoms. The association between employment, marital status, and mental health services was inconclusive due to limited studies. High financial costs, lack of transportation, and scarcity of mental health services were structural factors found to be associated with lower rates of mental health service use. Attitudinal barriers, mental health stigma, and cultural beliefs also contributed to the lower rates of mental health service use.

This systematic review found that several socio-demographic characteristics were strongly associated with using mental health services. Policymakers and those providing mental health services can use this information to better understand and respond to inequalities in mental health service use and improve access to mental health treatment.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Mental disorders such as depression and anxiety are prevalent, with nationally representative studies showing that one-fifth of Australians experience a mental disorder each year [ 5 ]. More recent estimates derived from a similar survey during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic were 21.5% [ 11 ]. Mental illness can reduce the quality of life, and increase the likelihood of communicable and non-communicable diseases [ 116 , 137 ], and is among the costliest burdens in developed countries [ 22 , 34 , 80 ]. The National Mental Health Commission [ 96 ] stated that the annual cost of mental ill-health in Australia was around $4000 per person or $60 billion. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019 reported that mental disorders rank the seventh leading cause of disability-adjusted life years and the second leading cause of years lived with disability [ 48 ]. Helliwell et al. [ 56 ] indicated that chronic mental illness was a key determinant of unhappiness, and it triggered more pain than physical illness. Mental health issues can have a spillover effect on all areas of life, poor mental health conditions might lead to lower educational achievements and work performance, substance abuse, and violence [ 102 ]. In Australia, despite considerable additional investment in the provision of mental health services research suggests that the rate of psychological distress at the population level has been increasing [ 38 ], this has been argued to reflect that people who most need mental health treatment are not accessing services. Insufficient numbers of mental health services and mental healthcare professionals and inadequate health literacy have been reported as the pivotal determinants of poor mental health [ 18 ]. Previous studies have reported large treatment gaps in mental health services; finding only 42–44% of individuals with mental illness seek help from any medical or professional service provider [ 85 , 112 ] and this active proportion was much lower in low and middle-income countries [ 32 , 114 , 130 ].

Several studies have investigated factors associated with high and low rates of mental health service use and identified potential barriers to accessing mental health service use. Demographic, social, and structural factors have been associated with low rates of mental health service use. Structural barriers include the availability of mental health services and high treatment costs, social barriers to treatment access include stigma around mental health [ 125 ], fear of being perceived as weak or stigmatized [ 79 ], lack of awareness of mental disorders, and cultural stigma [ 17 ].

Existing studies that have systematically reviewed and evaluated the literature examining mental health service use have largely been constrained to specific population groups such as military service members [ 63 ] and immigrants [ 33 ], children and adolescents [ 35 ], young adults [ 76 ], and help-seeking among Filipinos in the Philippines [ 93 ]. These systematic reviews emphasize mental health service use by specific age groups or sub-groups, and the findings might not represent the patterns and barriers to mental health service use in the general population. One paper has reviewed mental health service use in the general adult population. Roberts et al. [ 112 ] found that need factors (e.g. health status, disability, duration of symptoms) were the strongest determinants of health service use for those with mental disorders.

The study results from Roberts et al. [ 112 ] were retrieved in 2016, and the current study seeks to build on this prior review with more recent research data by identifying publications since 2012 on mental health service use with a focus on high-income countries. This is in the context of ongoing community discussion and reform of the design and delivery of mental health services in Australia [ 140 ], and the need for current evidence to inform this discussion in Australia and other high-income countries. This systematic review aims to investigate factors associated with mental health service use among people with mental disorders and summarize the major barriers to mental health treatment. The specific objectives are (1) to identify factors associated with mental health service use among people with mental disorders in high-income countries, and (2) to identify commonly reported barriers to mental health service use.

Methodology

Selection procedures.

Our review adhered to PRISMA guidelines to present the results. We utilized PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of Science to search for articles describing the facilitators and barriers to mental health service use among people with mental illness from January 2012 up to August 2023. There were no specific factors that were of interest as part of conducting this systematic review, instead, the review had a broad focus intending to identify factors shown to be associated with mental health service use in the recent literature. The keywords used in our search of electronic databases were related to mental disorders and mental health service use. The full search terms and strategies were shown in Supplementary Table 1. We uploaded the search results to Covidence for deduplication and screening. After eliminating duplicates, the first author retrieved the title abstract and full-text articles for all eligible papers. Then each title and abstract were screened by two independent reviewers, to select those that would progress to full-text review. Subsequently, the two reviewers screened the full text of all the selected papers and conducted the data extraction for those that met the eligibility criteria. There were discrepancies in 12% of the papers reviewed, and all conflicts were resolved through discussion and agreed on by at least three authors.

Selection criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

In this systematic review, the scope was restricted to studies that draw samples from the general population, and the participants were either diagnosed with mental disorders or screened positive using a standardized scale. Case-control studies and cohort studies were considered for inclusion. The applied inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1 .

Data extraction

After the full-text screening, details from all eligible studies were extracted by field into a data extraction table with thematic headings. The descriptive data includes the study title, author, publication year, geographic location, sample size, population details (gender, age), type of study design, mental disorder type (medical diagnosis or using scales) and quality grade (e.g. good, fair, and poor).

Quality assessment

The Newcastle Ottawa Scale [ 136 ] was used to evaluate the study quality for all eligible papers. We assessed the cross-sectional and cohort studies using separate assessment forms and graded each study as good, fair, or poor. The quality grade for each study was included in the data extraction table. The first author conducted the quality assessment using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale for cohort studies and the adapted scale for cross-sectional studies.

The search process is summarized in Fig. 1 . The initial search from PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of Science yielded 3230 articles: 2366 remained after removing duplicates; 2129 studies were considered not relevant; and 237 studies remained following title and abstract screening. In total, 40 studies met the inclusion criteria. Of these, four were cohort studies while thirty-six were cross-sectional studies. Ten studies (25.0%) were conducted in Canada, and nine (22.5%) were from the United States. Three studies used data from Germany (7.5%). Two studies each reported data from Australia, Denmark, Sweden, Singapore, or South Korea (5.0% of studies for each country). A single study was included with data from either the United Kingdom, Italy, Israel, Portugal, Switzerland, Chile, New Zealand, or reported pooled multinational data from six European countries (each country/ study representing 2.5% of the total sample of studies) (Table 2 ).

Flowchart for selections of studies

Study characteristics

As shown in Tables 2 , 3 and 4 , the sample size of studies varies; a cross-sectional study from Canada had the largest sample which contained over seven million participants [ 39 ], while the smallest sample size was 362 [ 100 ]. Sixteen studies (40.0%) used DSM-IV diagnoses [ 4 ] to measure mental disorders, twelve studies (30.0%) applied the International Classification of Disease [ 138 ], and six studies used (15.0%) the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [ 69 ]. Only three studies (7.5%) had a hospital diagnosis of mental disorders, while three studies (7.5%) used the Patient Health Questionnaire [ 72 ] to define mental disorders.

Twenty-seven studies (67.5%) analyzed the rate of mental health service use over the last 12 months, six studies (15.0%) focused on lifetime service use, and three studies (7.5%) assessed both 12-month and lifetime mental health service use. A few studies examined other time frames, with single studies investigating mental health service use over the past 3 months, 5 years, and 7 years, and one included study considered mental health service use during the 24 months before and after a sibling’s death.

Twenty of the forty studies were classified as good quality (50.0%), seventeen as fair (42.5%), and three as poor quality (7.5%).

Overview of samples and factors investigated

The included studies examined a range of different factors associated with mental health service use. These included gender, age, marital status, ethnic groups, alcohol and drug abuse, education and income level, employment status, symptom severity, and residential location. The review identified service utilization factors related to socio-demographics, differences in utilization across countries, emerging socio-demographic factors and contexts, as well as structural and attitudinal barriers. These are described in further detail below.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Fifteen studies analyzed the association between gender and mental health service use, with fourteen studies reporting that mental health service use was more frequent among females with mental disorders than males [ 2 , 37 , 42 , 43 , 47 , 54 , 66 , 67 , 90 , 103 , 119 , 123 , 128 , 130 ]. A South Korean study concluded that gender was not associated with mental health service use [ 100 ], which might be due to the small sample size of 362 participants in the study.

Fourteen studies investigated age in association with mental health service use. Nine studies concluded that mental health service use was lower among young and old adult groups, with middle-aged persons with a mental disorder being most likely to access treatment from a mental health professional [ 26 , 42 , 43 , 47 , 54 , 66 , 67 , 123 , 130 ]. Forslund et al. [ 43 ] reported that mental health service use for women in Sweden peaked in the 45-to-64-year age group, while amongst males, mental health service use was stable across the lifespan. In contrast, two articles from New Zealand and Singapore each reported that young adults were the age group most likely to access services [ 28 , 119 ]. Reich et al. [ 103 ] concluded that age was unrelated to mental health service use when considered for the whole population, but sex-specific analyses reported that mental health service use was higher in older than younger females, while the opposite pattern was observed for males. A Canadian study using community health survey data also observed no significant age-related differences in mental health service use [ 104 ].

Marital status

There was mixed evidence concerning marital status. Studies from the United States and Germany concluded that participants who were married or cohabiting had lower rates of mental health service use [ 26 , 90 ], while Silvia et al. [ 120 ] found that mental health service use was higher among married participants in Portugal. Shafie et al. [ 119 ] reported being widowed was associated with lower rates of mental health service use in Singapore.

Ethnic groups

Eight studies examined the relationship between ethnic background and mental healthcare service use. Non-Hispanic White respondents were more likely to use mental health services in Canada and the United States [ 24 , 26 , 30 , 130 , 139 ], while Asians showed lower rates of mental health service use [ 28 , 139 ]. Chow & Mulder [ 28 ] investigated mental health service use among Asians, Europeans, Maori, and Pacific peoples in New Zealand. They concluded that Maori had the highest rate of mental health service use compared with other ethnic groups. De Luca et al. [ 30 ] reported that mental health service use was lower among ethnic minority non-veterans compared to veterans in the United States, especially for those with Black or Hispanic backgrounds. In contrast, a study conducted in the UK found that mental health service use did not vary by ethnicity, with no difference between white and non-white persons [ 54 ].

Alcohol and drug abuse

Two studies reported risky alcohol use was negatively associated with mental health service use [ 26 , 132 ]. However, within the time frame of the current review, there was insufficient published evidence on the impact of drug abuse on mental health service use among people with mental disorders. Choi, Diana & Nathan [ 26 ] found that drug abuse can lead to lower rates of mental health service use in the United States. In contrast, Werlen et al. [ 132 ] reported that risky use of (non-prescribed) prescription medications was associated with higher rates of mental health service use in Switzerland.

Education, income, and employment status

Four studies analyzed the relationship between education level, income, and mental health service use. Higher levels of educational attainment [ 26 , 120 ] and higher income [ 26 ] were generally reported to be associated with an increased likelihood of mental health service use. However, Reich et al. [ 103 ] observed that in Germany, high education and perceived middle or high social class were associated with reduced mental health service use. One paper reported no significant difference in mental health service use in South Korea, possibly due to the small number of people accessing mental healthcare services [ 100 ].

Three studies reported that compared to those who are unemployed, those in work were less likely to use mental health services [ 26 , 90 , 119 ]. This outcome aligned with a Canadian study consisting of immigrants and general populations, Islam et al. [ 66 ] concluded that immigrants who were currently unemployed had higher odds of seeking treatment than those who were employed. However, an Italian [ 123 ] and a South Korean study [ 100 ] found that employment status was not related to mental health service use.

Symptom severity

Ten studies investigated the association between symptom severity and mental health service use and ten papers concluded that participants with moderate or serious psychological symptoms were more likely to use mental health services compared to those with mild symptoms [ 23 , 27 , 66 , 103 , 120 , 123 , 130 , 139 ]. Other studies showed that study participants who viewed their mental health as poor [ 42 ], who were diagnosed with more than one mental disorder [ 103 ], and those who recognized their own need for mental health treatment [ 54 , 139 ] were more likely to receive mental health services.

Residential location

Three studies investigated the association between residential location and mental health service use. Volkert et al. [ 128 ] concluded that the rates of mental health service use in Germany were significantly lower among those living in Canterbury than those living in Hamburg. A Canadian study found individuals living in neighborhoods where renters outnumber homeowners were less likely to access mental health services [ 42 ]. In the United States, for participants with low or moderate mental illness, mental health service use was lower for those residing closer to clinics [ 46 ].

Immigrants & refugees

The reviewed research found that non-refugee immigrants had slightly higher rates of mental health service use than refugees [ 10 ]. Other research found that long-term residents were more likely to access services than immigrants regardless of their origin [ 31 , 134 ]. For example, Italian citizens were found to have higher rates of mental health service use compared to immigrants, especially for affective disorders [ 123 ]. In Canada, immigrants from West and Central Africa were more likely to access mental health services compared to immigrants from East Asia and the Pacific [ 31 ]. Research from Chile found that the rates of mental health service use were similar for immigrants and non-immigrants [ 40 ]. Although, a positive association between the severity of symptoms and rates of mental health service use was only observed among immigrants [ 40 ]. Whitley et al. [ 134 ] found that immigrants born in Asia or Africa had lower rates of mental health service use, but higher rates of service satisfaction scores compared to immigrants from other countries.

Emerging areas

Our literature review identified several areas in which only a small number of studies were found. We briefly describe them here as these may reflect emerging areas of research interest. Few published articles examined mental health treatment among participants with mental disorders together with chronic physical health conditions, and we only included the papers in this systematic review if they contained a healthy comparison group. We identified two papers that focused on survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer [ 68 ] and participants with physical health problems [ 110 ]. Both studies reported that participants with other chronic conditions reported higher rates of mental health service use than the general population [ 68 , 110 ].

Two studies compared treatment seeking among people experiencing stressful life events. Erlangsen et al. [ 39 ] investigated the impact of spousal suicide, and Gazibara et al. [ 45 ] examined the effect of a sibling’s death on mental health service use. People bereaved by relatives’ deaths were more likely to use mental health services than the general population [ 39 , 45 ]. The peak effect was observed in the first 3 months after the death for both genders, while evidence of an increase in mental health service use was evident up to 24 months before a sibling’s death and remained evident for at least 24 months after the death [ 45 ].

One paper studied the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on mental health service use. An Israeli study concluded that compared to 2018 and 2019, adults reported they were reluctant to receive treatment during the pandemic lockdown and observed a decrease in mental health service use [ 13 ].

Structural and attitudinal barriers

In addition to the research considering a range of population characteristics (e.g. male, younger, or older age), several papers examined how attitudinal and structural factors were associated with mental health service use. The most frequently reported of these factors were cost [ 23 , 46 , 68 , 120 ], lack of transportation [ 46 , 83 ], inadequate services/ lack of availability [ 23 , 46 , 83 , 128 ], poor understanding of mental disorders and what services were available [ 10 , 11 , 22 , 83 , 100 , 105 , 120 ], language difficulties [ 10 ], and stigma-related barriers [ 83 , 100 , 103 , 105 , 128 ]. Cultural issues and personal beliefs may influence the understanding of mental disorders and prevent people from using mental health services due to mistrust or fear of treatment [ 100 , 128 ]. The review also observed some unique barriers to different population groups. Choi, Diana & Nathan [ 26 ] mentioned that lack of readiness and treatment cost were the biggest difficulties for older adults, while young participants were more concerned about stigma. Females also reported childcare as a factor limiting their ability to use mental health services, while the evidence reviewed argued that males prefer to solve mental health issues on their own, with internal control beliefs and lack of social support likely reducing their use of mental health services [ 37 , 103 ].

Summary of evidence

This systematic review investigated mental health service use among people with mental disorders and identified the factors associated with service use in high-income countries.

Most studies found that females with mental health conditions were more likely to use mental health services than males. The relationship between age and mental health service use was bell-shaped, with middle-aged participants having higher rates of mental health service use than other age groups. Possible explanations included that the elderly might be reluctant to disclose mental health symptoms, they might attribute their mental health symptoms to increasing age [ 20 ], and they may prefer to self-manage instead of seeking help from health professionals [ 44 ]. Caucasian ethnicity and higher household income were also associated with higher rates of mental health service use. Greater use of mental health services was observed in participants with severe mental symptoms, including among veterans [ 19 , 37 , 92 ]. Two studies also concluded that compared to other cultural groups, Asian respondents were more likely to receive treatment when problems were severe or had disabling effects [ 86 , 97 ]. There was mixed evidence regarding employment status, although some studies found employment to be negatively related to receiving treatment [ 26 , 90 ], and unemployed people are more likely to seek help [ 119 ]. There was inconsistent evidence for the association between marital status and service utilization. This contradictory evidence on marital status might be attributed to a lack of specification, some papers categorize it as married and non-married [ 26 , 71 , 131 ], while others further differentiate between those who were widowed, separated, and divorced [ 90 , 119 ].

A number of studies showed that immigrants can face unique stressors owing to their experience of migration, which may exacerbate or be the source of their mental health issues, and impact the use of mental health services [ 1 , 8 ]. These include separation from families, support networks, linguistic and cultural barriers [ 9 , 113 ].

Due to the increased number of international migrants, immigrants’ mental health status and healthcare use has drawn growing attention [ 7 , 77 , 99 ]. Kirmayer et al. [ 70 ] and Helman [ 57 ] found that culture might be associated with people’s attitudes and understanding of mental health, influencing help-seeking behaviors. In general, the current results showed that immigrants and refugees were less likely to use mental health services than their native-born counterparts, and this finding was consistent with previous studies [ 75 , 82 , 127 ]. For immigrants, the length of stay in the host country was closely related to rates of mental health service use, which was argued to reflect increasing familiarity with the host culture and language proficiency [ 1 , 59 ].

Both mental disorders and chronic diseases contribute significantly to the global burden of disease. Prior studies have shown that people with chronic disease have a higher chance of experiencing psychological distress [ 6 , 14 , 68 , 73 ], and vice versa [ 49 , 74 ]. Hendrie et al. [ 58 ] concluded that respondents with chronic diseases were more likely to attend mental healthcare and reported higher costs. Negative experiences and stressful consequences related to chronic disease might contribute to the increased potential for mental illness but more opportunities to seek help from health professionals [ 60 , 108 , 135 ]. People with chronic diseases and mental health problems might experience more long-term pain and limitations in their daily lives, and these stressors can exacerbate their health conditions, and impact their attitude toward seeking help.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on mental health service use worldwide, the hospital admission and consultation rate decreased dramatically during the first pandemic year [ 118 ]. This reduction in service access might be a side effect of social distancing measures taken as mitigation measures, reducing both inciting incidents and physical access to services.

Financial difficulty, service availability, and stigma were frequently identified in the literature as structural and attitudinal factors associated with lower rates of mental health service use. These factors were associated with the different rates of mental health service use for different ethnicities. For example, Asian people were less likely than other groups to identify cost as a factor limiting their use of mental health services, with a major barrier for Asian people being stigma and cultural factors [ 139 ].

Limitations

This systematic review employed a broad search strategy with broad search terms to capture relevant articles. Rather than emphasizing a particular mental disorder, this review focused on the rates of mental health service use among adults aged 18 years or older who were experiencing a common mental disorder. However, this review still contained limitations. First was the potential for selection bias. Although we used various search terms for mental health service use and mental disorder, it is possible that the service use was not the primary research question for some papers, or that the relevant service use outcome was not statistically significant- in these cases, if the information was not reported in the abstract, relevant papers might have been missed. It is also important to note that this systematic review includes studies conducted in different countries and that the mental health systems and opportunities for access vary among countries. We only searched for full-text peer-reviewed articles published in English. Grey literature and papers published in other languages were excluded from the search. Most of the included literature used self-reported data to measure service access, and these data can be liable to recall bias. Studies using administrative data were also included in the systematic review, and we note that although they have large datasets, compared to survey data, there is often a lack of adequate control variables included to minimize possible confounding influences.

Future research

There is a need for more published articles on several aspects that may influence the service utilization among people with mental disorders, including the impact of residential or neighborhood areas, and household income across various income groups. These aspects are important population characteristics that require further research to inform the targeting and type of support (e.g. low-cost, accessible). Additionally, there was a lack of longitudinal research on mental health service use, future studies could use the data to identify changes over time and relate events to specific exposures (e.g. Covid-19 pandemic). Future studies can investigate the cost of mental health treatment in detailed aspects, (e.g. publicly funded mental health services, community-based support for free or low-cost mental health services). Overall, there was a lack of studies for ethnic minorities, given ethnic minority groups were more vulnerable to mental disorders but with less mental health service use. Future research can expand gender identity representation in data collection and move beyond the binary genders. People with non-binary gender identities can face greater challenges and disadvantages in mental health and mental health service use.

This review identified that middle-aged, female gender, Caucasian ethnicity, and severity of mental disorder symptoms were factors consistently associated with higher rates of mental health service use among people with a mental disorder. In comparison, the influence of employment and marital status on mental health service use was unclear due to the limited number of published studies and/ or mixed results. Financial difficulty, stigma, lack of transportation, and inadequate mental health services were the structural barriers most consistently identified as being associated with lower rates of mental health service use. Finally, ethnicity and immigrant status were also associated with differences in understanding of mental health (i.e. mental health literacy), effectiveness of mental health treatments, as well as language difficulties. The insights gained through this review on the factors associated with mental health service use can help clinicians and policymakers to identify and provide more targeted support for those least likely to access services, and this in turn may contribute to reducing inequalities in not only mental health service use but also the burden of mental disorders.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials related to the study are available on request from the first author, [email protected].

Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer MS, et al. Use of mental health–related services among immigrant and US-born Asian americans: results from the national latino and Asian American study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):91–8.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Abramovich A, De Oliveira C, Kiran T, Iwajomo T, Ross LE, Kurdyak P. Assessment of health conditions and health service use among transgender patients in Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2015036. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15036 .

Ambikile JS, Iseselo MK. Mental health care and delivery system at Temeke hospital in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1271-9 .

Article Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017-18, Mental health, ABS, viewed 23 July 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/mental-health/2017-18 .

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1069–78.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bacon L, Bourne R, Oakley C, Humphreys M. Immigration policy: implications for mental health services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2010;16:124–32.

Bhatia S, Ram A. Theorizing identity in transnational and diaspora cultures: a critical approach to acculturation. Int J Intercultural Relations. 2009;33:140–9.

Bhugra D. Migration, distress and cultural identity. Br Med Bull. 2004;69:129–41.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Björkenstam E, Helgesson M, Norredam M, Sijbrandij M, de Montgomery CJ, Mittendorfer-Rutz E. Differences in psychiatric care utilization between refugees, non-refugee migrants and Swedish-born youth. Psychol Med. 2022;52(7):1365–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720003190 .

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020–2022). National study of mental health and wellbeing. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release .

Blais RK, Tsai J, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Barriers and facilitators related to mental health care use among older veterans in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(5):500–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300469 .

Blasbalg U, Sinai D, Arnon S, Hermon Y, Toren P. Mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a large-scale population-based study in Israel. Compr Psychiatr. 2023;123:123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152383 .

Bodurka-Bevers D, Basen-Engquist K, Carmack CL, Fitzgerald MA, Wolf JK, Moor Cd, Gershenson DM. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with epthelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:302–8.

Bondesson E, Alpar T, Petersson IF, Schelin MEC, Jöud A. Health care utilization among individuals who die by suicide as compared to the general population: a population-based register study in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1616. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14006-x

Borges G, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Andrade L, Benjet C, Cia A, Kessler RC, Orozco R, Sampson N, Stagnaro JC, Torres Y, Viana MC, Medina-Mora ME. Twelve-month mental health service use in six countries of the Americas: a regional report from the World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e53. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796019000477 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brenman NF, Luitel NP, Mall S, Jordans MJD. Demand and access to mental health services: a qualitative formative study in Nepal. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014;14(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-14-22 . PMID: 25084826.

Budhathoki SS, Pokharel PK, Good S, Limbu S, Bhattachan M, Osborne RH. The potential of health literacy to address the health related UN sustainable development goal 3 (SDG3) in Nepal: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1943-z . PMID: 28049468.

Brown JS, Evans-Lacko S, Aschan L, Henderson MJ, Hatch SL, Hotopf M. Seeking informal and formal help for mental health problems in the community: a secondary analysis from a psychiatric morbidity survey in South London. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):275.

Burroughs H, Lovell K, Morley M, Baldwin R, Burns A, Chew-Graham C. Justifiable depression’: how primary care professionals and patients view late-life depression? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):369–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmi115 .

Caron J, Fleury MJ, Perreault M, Crocker A, Tremblay J, Tousignant M, Kestens Y, Cargo M, Daniel M. Prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders, and use of mental health services in the epidemiological catchment area of Montreal South-West. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-183 .

Chan CMH, Ng SL, In S, Wee LH, Siau CS. Predictors of psychological distress and mental health resource utilization among employees in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010314 .

Chaudhry MM, Banta JE, McCleary K, Mataya R, Banta JM. Psychological distress, structural barriers, and health services utilization among U.S. adults: National Health interview survey, 2011–2017. Int J Mental Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2022.2123694

Chiu M, Amartey A, Wang X, Kurdyak P, Luppa M, Giersdorf J, Riedel-Heller S, Prütz F, Rommel A. Ethnic differences in mental health status and service utilization: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada frequent attenders in the German healthcare system: determinants of high utilization of primary care services. Results from the cross-sectional. Can J PsychiatryBMC Fam Pract. 2018;6321(71):481–91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-1082-9 .

Cho SJ, Lee JY, Hong JP, Lee HB, Cho MJ, Hahm BJ. Mental health service use in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:943–51.

Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN. Treatment use, perceived need, and barriers to seeking treatment for substance abuse and mental health problems among older adults compared to younger adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:113–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.004 .

Chong SA, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Kwok KW, Subramaniam M. Where do people with mental disorders in Singapore go to for help? Ann Acad Med Singap. 2012;41(4):154–60.

Chow CS, Mulder RT. Mental health service use by asians: a New Zealand census. N Z Med J. 2017;130(1461):35–41.

PubMed Google Scholar

Dang HM, Lam TT, Dao A, Weiss B. Mental health literacy at the public health level in low and middle income countries: an exploratory mixed methods study in Vietnam. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0244573. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244573

De Luca SM, Blosnich JR, Hentschel EA, King E, Amen S. Mental health care utilization: how race, ethnicity and veteran status are associated with seeking help. Community Ment Health J. 2016;52(2):174–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9964-3 .

Durbin A, Moineddin R, Lin E, Steele LS, Glazier RH. Mental health service use by recent immigrants from different world regions and by non-immigrants in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0995-9

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine J, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581–90.

Derr AS. Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67:265–74. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500004 .

Dimoff JK, Kelloway EK. With a little help from my Boss: the impact of workplace mental health training on leader behaviors and employee resource utilization. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24:4–19.

Duong MT, Bruns EJ, Lee K, et al. Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2021;48:420–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01080-9 .

Edman JL, Kameoka VA. Cultural differences in illness schemas: an analysis of Filipino and American illness attributions. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1997;28(3):252–65.

Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Johnson SC, Kinneer P, Kang H, Vasterling JJ, Timko C, Beckham JC. Are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using mental health services? New data from a national random-sample survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(2):134–41. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.004792011 .

Enticott J, Dawadi S, Shawyer F, Inder B, Fossey E, Teede H, Rosenberg S, Ozols Am I, Meadows G. Mental Health in Australia: psychological distress reported in six consecutive cross-sectional national surveys from 2001 to 2018. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:815904. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.815904

Erlangsen A, Runeson B, Bolton JM, Wilcox HC, Forman JL, Krogh J, Katherine Shear M, Nordentoft M, Conwell Y. Association between spousal suicide and mental, physical, and social health outcomes a longitudinal and nationwide register-based study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):456–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0226 .

Errazuriz A, Schmidt K, Valenzuela P, Pino R, Jones PB. Common mental disorders in Peruvian immigrant in Chile: a comparison with the host population. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1274. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15793-7

Evans-Lacko S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, Florescu S, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, He Y, Hu C, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lund C, Kovess-Masfety V, Levinson D, Thornicroft G. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1560–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717003336 .

Fleury MJ, Grenier G, Bamvita JM, Perreault M, Kestens Y, Caron J. Comprehensive determinants of health service utilisation for mental health reasons in a Canadian catchment area. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-20

Forslund T, Kosidou K, Wicks S, Dalman C. Trends in psychiatric diagnoses, medications and psychological therapies in a large Swedish region: a population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):328. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02749-z

Garrido MM, Kane RL, Kaas M, Kane RA. Use of mental health care by community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):50–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03220.x .

Gazibara T, Ornstein KA, Gillezeau C, Aldridge M, Groenvold M, Nordentoft M, Thygesen LC. Bereavement among adult siblings: an examination of health services utilization and mental health outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(12):2571–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab212 .

Glasheen C, Forman-Hoffman VL, Hedden S, Ridenour TA, Wang J, Porter JD. Residential transience among adults: prevalence, characteristics, and association with mental illness and mental health service use. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55(5):784–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00385-w .

Gonçalves DC, Coelho CM, Byrne GJ. The use of healthcare services for mental health problems by middle-aged and older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(2):393–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2014.04.013 .

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar