An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Domestic Violence in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Synthesis of Systematic Reviews

Meghan royle.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Bitna Kim, Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology, College of Criminal Justice, Sam Houston State University, PO Box 2296, Huntsville, TX 77341, USA. Email: [email protected]

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until permissions are revoked in writing. Upon expiration of these permissions, PMC is granted a perpetual license to make this article available via PMC and Europe PMC, consistent with existing copyright protections.

The current systematic meta-review aimed to map out, characterize, analyze, and synthesize the overarching findings of systematic reviews on domestic violence (DV) in the context of COVID-19. Specifically, a systematic meta-review was conducted with three main objectives: (1) to identify what types and aspects of DV during COVID-19 have been reviewed systematically to date (research trends), (2) to synthesize the findings from recent systematic reviews of the theoretical and empirical literature (main findings), and (3) to discuss what systematic reviewers have proposed about implications for policy and practice as well as for future primary research (implications). We identified, appraised, and synthesized the evidence contained in systematic reviews by means of a so-called systematic meta-review. In all, 15 systematic reviews were found to be eligible for inclusion in the current review. Thematic codes were applied to each finding or implication in accordance with a set of predetermined categories informed by the DV literature. The findings of this review provide clear insight into current knowledge of prevalence, incidence, and contributing factors, which could help to develop evidence-informed DV prevention and intervention strategies during COVID-19 and future extreme events. This systematic meta-review does offer a first comprehensive overview of the research landscape on this subject. It allows scholars, practitioners, and policymakers to recognize initial patterns in DV during COVID-19, identify overlooked areas that need to be investigated and understood further, and adjust research methods that will lead to more robust studies.

Keywords: domestic violence, family violence, COVID-19, systematic meta-review

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic violence 1 (DV)— any form of physical, psychological, sexual, economic, or other violence and abuse occurring within the family or domestic setting, including violence against adults (partners, elders, adult children, or adult siblings) as well as minors (children and adolescents) ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Lausi et al., 2021 )—has become a significant issue worldwide, as movement restrictions and lockdown measures force DV victims to spend more time at home with their abusers ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ). Survivors are already isolated to some extent, but quarantine and lockdown have further compounded their situation. This double isolation is characterized by the absence of formal or informal support networks, enabling perpetrators to act without scrutiny or repercussions ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). As Viero et al. (2021) describe, the stay-at-home (SAH) mantra becomes a paradox in the DV context ( Viero et al., 2021 ).

While DV has been a worldwide concern during the COVID-19 pandemic, studies of past epidemics and natural disasters that document their impacts on DV experience and reporting, as well as changes in the delivery of violence prevention and response services, show mixed results ( Piquero et al., 2021 ). Researchers found that the 2014 outbreak of Ebola in West and Central Africa and the 2017 outbreak of cholera in Yemen both led to elevated rates of DV, as well as disruptions in welfare structures, communities, and protection responses ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ). A growing body of research indicates, however, that pandemics and natural disasters reduce violent crime, boost family functioning, and enhance prosocial behavior within communities and families by preserving community trust or strengthening cooperation ( Cerna-Turoff et al., 2019 ).

In Cerna-Turoff et al. (2019) , the first known systematic review and meta-analysis on the topic of epidemics’ and natural disasters’ impacts on violent crime, the researchers investigated the magnitude and direction of the association between natural disasters and various forms of child abuse (CA) within the family or domestic context. They found no consistent association or directional influence between natural disasters and CA. As a result, they suggested that this finding challenges the assumption that DV escalates when epidemics and natural disasters strike. Cerna-Turoff et al. (2019) cautioned, however, that a concrete conclusion could not be reached due to the lack of studies on the subject.

Researchers across the globe have moved quickly to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between DV and COVID-19 and to identify emerging issues related to DV within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, as evidenced by an increasing body of primary research ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ). A systematic review approach has become increasingly common across the disciplines in researching DV associated with COVID-19, as the DV literature continues to grow at a rapid rate. To be able to respond to DV not only during the current COVID-19 pandemic, but also in future pandemics, systematic reviewers have synthesized international findings concerning issues surrounding DV about which researchers, practitioners, and policymakers must remain informed and ready to continue exploring ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ). Recently, the proliferation of systematic reviews on DV during the COVID-19 pandemic has made it challenging to keep up. It is arguably imperative to synthesize the overarching findings of systematic reviews on DV and aim to further advance both researchers’ and policymakers’ efforts to prevent DV during COVID-19 and future extreme events ( Marmor et al., 2021 ).

Current Research

Through the use of a systematic meta-review approach, we located systematic reviews of DV during the COVID-19 published across a range of disciplines, synthesized their findings, and identified DV-specific themes pertaining to policy, practice, and future research implications.

As such, the current systematic meta-review aimed to map out, characterize, and analyze all of the empirical evidence for DV within the context of COVID-19 ( Marmor et al., 2021 ). Specifically, three main objectives guided our systematic meta-review: (1) identifying which types and aspects of DV have been reviewed systematically during COVID-19 (research trends), (2) synthesizing the recent systematic review findings (main findings), and (3) contemplating the implications that systematic reviewers have proposed for policy and practice as well as future primary research (implications). Lastly, this study concluded with recommendations for future systematic reviews of DV during the pandemic based on its synthesis findings.

As the first systematic meta-review of DV in the context of COVID-19, the current review provides a comprehensive overview of the research landscape. The findings will enable scholars to recognize initial patterns in DV during COVID-19, identify areas that need further exploration and understanding, and adapt methods to develop more robust studies ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ). Furthermore, those who assess and intervene with potential DV offenders and victims may find the current systematic meta-review of great interest, as it may provide guidance for tailoring prevention/intervention strategies.

Inclusion Criteria

Only systematic reviews of DVs in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic were eligible for inclusion. Specifically, to be included in the current “systematic meta-review” (i.e., a synthesis of systematic reviews), a systematic review had to meet the following criteria: (1) searched at least one database, in addition to reference checking, hand-searching, citation searching, or contacting primary research authors ( Gibson et al., 2011 ), (2) were published in a peer-reviewed journal using publication as a proxy for research quality ( Kim & Merlo, 2021 ; Pratt, 2010 ), and (3) reviewed the existing literature on DV in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. DV encompasses intimate partner violence (IPV), elder abuse, CA, and any form of violence within the family or domestic setting ( Abdo et al., 2020 ).

Search Strategy and Identified Studies

It is necessary to identify, appraise, and synthesize the evidence contained in systematic reviews by means of systematic meta-review ( Gibson et al., 2011 ; Kim & Merlo, 2021 ). A systematic meta-review approach brings several advantages, including exhaustive literature searches and the ability to synthesize large amounts of information ( Cervero & Gaines, 2015 ; Jaspers et al., 2011 ). Following the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines ( Moher et al., 2009 ), two researchers searched through a number of online databases in December 2021, and the search was subsequently updated in March 2022, August 2022, and November 2022. We sought to identify all systematic reviews of DV during the pandemic published in peer-reviewed journals that were available (either in print or in electronic form) that met the inclusion criteria for this review.

The specific electronic databases used were as follows: Criminal Justice Abstracts, Criminology: A Sage Full-Text Collection, Sociological Abstracts, PsychINFO, MEDLINE, Social Science Abstracts, Psychological & Behavioral Science Collection, Health and Safety Science Abstracts, and Current Contents. The following Boolean search strings were used: (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “novel coronavirus” OR “coronavirus”) AND (“domestic violence” OR “domestic abuse” OR “family violence” OR “violence against women” OR “violence against children” “intimate partner violence” OR “abuse” OR “maltreatment” OR “vulnerability” OR “assault”) ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; McNeil et al., 2022 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ).

Hand searches were conducted in two premier journals for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in violence: Trauma, Violence, & Abuse and Aggression and Violent Behaviors (2020–2022). The titles and abstracts of all studies published in Child Abuse and Neglect (2020–2022), where review studies are frequently published, were also reviewed. The search looked for any mention in the title, the abstract, or the keyword list of the words “systematic review” or “literature review” paired with any of the following terms: domestic violence, domestic abuse, child abuse, and family violence. In addition, the reference lists of those articles retrieved from each of the databases and journals were scanned to identify additional systematic review studies. As the last step, after obtaining the initial sample studies through online databases, reference lists, and journals, we checked Google Scholar using the authors’ names to locate studies by the active researchers cited ( Kim & Merlo, 2021 ).

We attempted to obtain copies of each likely candidate and the abstracts of likely references were reviewed to ensure that they used a systematic review approach. In the full-text review, each paper was evaluated according to the inclusionary criteria. As a result of these search strategies and inclusion criteria, 17 systematic reviews were found to be eligible for inclusion in the current review. Supplemental Appendix 1 depicts a PRISMA diagram of the study selection process.

Data Extraction and Coding

Two researchers independently extracted and coded information from each eligible study according to the review protocol. During coding, the primary focus was on identifying and coding study characteristics, main findings, and implications for policy and future research. To achieve this, we followed Wilson et al.’s (2019) meta-aggregation screening and coding procedure. Thematic codes were applied to each finding or implication in accordance with a set of predetermined categories informed by the DV literature. During the coding process, additional thematic codes were created and refined to better capture the underlying themes of a particular finding or implication. Cases of discrepancies in coding were moderated through consultation and agreement ( Kim & Merlo, 2021 ).

Research Trends: Characteristics of Eligible Systematic Reviews

Table 1 displays the study characteristics (i.e., authors’ disciplines, DV types, types of included studies, number of included studies, and national origins of included studies) as well as the main research questions of eligible systematic reviews. The systematic reviews were conducted in a variety of disciplines, including CCJ, gender studies, forensic and legal medicine, social work, education and health gynecology, psychology, psychiatry, medical science, education and humanities, child studies, and nursing. This result reflects that multiple disciplines recognize the seriousness of DV in the context of COVID-19 ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ).

Characteristics of Eligible Systematic Reviews ( N = 17).

CM = child maltreatment; DV = domestic violence; IPV = intimate partner violence; VAC = violence against children; VAW = violence against women.

Table 1 lists and groups the systematic reviews according to DV type. Nine synthesized the existing research findings on IPV against women ( Bayu, 2020 ; Lausi et al., 2021 ; McNeil et al., 2022 ; Moreira & da Costa, 2020 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ), four covered CA ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ; Rapp et al., 2021 ), and four covered DV against any member of the family (Javed & Mehmood, 2002; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Su et al., 2021 ; Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ). The literature reviewed consists primarily of journal articles, but six systematic reviews ( Bayu, 2020 ; Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ) also included narrative reviews, case studies, forum reports, working papers, commentaries, and letters to editors, which added interesting new insights. In systematic reviews, the number of included studies varied widely, from 3 ( Abdo et al., 2020 ) to 80 ( Bayu, 2020 ). The geographic areas covered by the systematic reviews were varied. Aside from Abdo et al. (2020) , which examined only US-based studies, the remaining 13 reviewed primary studies from multiple countries.

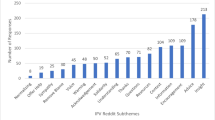

The four main research questions were addressed in systematic reviews, including prevalence and incidence ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Bayu, 2020 ; Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Lausi et al., 2021 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ; McNeil et al., 2022 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ; Rapp et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ; Viero et al., 2021 ), contributing factors ( Bayu, 2020 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; McNeil et al., 2022 ; Moreira & da Costa, 2020 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Rapp et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ; Viero et al., 2021 ), mitigating policies and practices ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Su et al., 2021 ), and emerging issues and patterns of DV studies ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ).

A synthesis of the main findings

Table 2 presents the main findings of each systematic review. The sequence of studies in Table 2 is identical to the one in Table 1 . That is, the studies in Table 2 are listed by DV type. This section presents the main findings according to the research questions and types of DV.

Main Findings.

CM = child maltreatment; DV = domestic violence; IPV = intimate partner violence; SAH = stay at home; VAW = violence against women.

Prevalence and incidence

Several reviews have been conducted to estimate the effect of COVID-19-related restrictions (i.e., SAH orders, lockdown orders) on reporting of DV incidents ( Bayu, 2020 ; Lausi et al., 2021 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ). While several systematic reviews demonstrate that DV cases have increased in most countries during the current outbreak of COVID-19 ( McNeil et al., 2022 ), others suggest that DV has declined significantly over the same period ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ). It has become evident that DV rates differ significantly between data reported by victims and those reported by help professionals (i.e., police officers, anti-DV workers, and healthcare providers) in addition to country-specific variations ( Lausi et al., 2021 ).

IPV against women : As a result of COVID-19 and movement restrictions, many women were confined at home with their abusers while social protection services for them were disrupted, thereby increasing IPV risk ( Bayu, 2020 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ). Basically, systematic reviews have concluded that a “lockdown” at home policy to counter the pandemic has aggravated the problem of IPV against women, causing what the UN has referred to as a “pandemic on a pandemic” ( Bayu, 2020 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; McNeil et al., 2022 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ). Viero et al.’s (2021) systematic review, for example, discovered a massive increase in IPV-related calls as well as police reports in Argentina, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the United States once restrictions were put in place to combat the outbreak. In addition, the systematic reviews provided information about specific circumstances associated with increasing IPV in the COVID-19 context. Globally, DV increased in the first week following the COVID-19 lockdown, according to Kourti et al. (2021) . Sánchez et al. (2020) also note that IPV against women has been increasing not only among low- and middle-income nations but also in high-income regions where social distancing measures are in place.

The COVID-19 lockdown has generally been acknowledged to be a substantial issue regarding IPV; however, some systematic reviewers have introduced primary studies that present a different picture ( Kourti et al., 2021 ). As an example, Viero et al. (2021) reported a dramatic decline in IPV victim requests for help during the lockdown. Nevertheless, Viero et al. (2021) , along with other systematic reviewers, caution that this result should not be interpreted as indicating a reduction in IPV cases since home confinement can limit victims’ access to help ( Kourti et al., 2021 ).

Among the systematic reviews in the current systematic meta-review studies, Piquero et al. (2021) precisely estimated the effect sizes of COVID-19-related restrictions on IPV incident reports by conducting a meta-analysis. The findings of this meta-analysis were based on police crime/incident reports, police calls for service, hotline registries, and health records before and after COVID-19 restrictions. An analysis of primary study results revealed that 29 studies reported an increase in IPV post-lockdowns, while eight studies reported a decrease. The meta-analysis results showed that SAH/lockdown orders caused a 7.86% increase in IPV incidents, and the effects increased, even more, when only US studies were considered, showing that 8.10% more incidents occurred.

For assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on IPV, Lausi et al. (2021) synthesized the results of studies comparing IPV rates before and after the SAH policies were implemented. Importantly, they divided IPV studies into categories based on data sources and compared data from victims (e.g., data collected from anonymous online surveys) with those from help professionals (e.g., help lines, healthcare system, or police system). It was found that IPV rates differed substantially between data sources and between countries. Studies with victim data showed an increase in IPV during SAH policies, particularly verbal, emotional, and psychological violence. Physical assault episodes decreased, but their severity worsened. Among the findings of this study, most female IPV victims reported that they did not seek help or report that abuse to authorities during the SAH period.

In contrast to studies with victim surveys, based on data from help professionals, the number of victims contacting hospitals and calling helplines during the pandemic appeared to be lower than in previous years. Lausi et al. (2021) included five studies using data collected from police reports. Mixed results were found in these studies. IPV increased by 8.1% during the pandemic period compared to the same period in previous years, according to a UK study. Specifically, IPV calls from third parties (e.g., neighbors) and high-density areas increased. In contrast, both US and Australian studies found no significant differences in IPV over the SAH period. Finally, Mexico City’s Attorney General’s office reported a significant decrease in IPV. In an explanation of these mixed responses, Lausi et al. (2021) claimed both increases and decreases were due to the increased IPV (e.g., fewer police calls due to increased stalking and control by abusers).

CA : The prevalence and incidence of CA within the family or domestic context have been examined in several systematic reviews ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ; Rapp et al., 2021 ). Compared to IPV against women, the number of police and social service reports of CA declined significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Kourti et al. (2021) , decreased rates during the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely due to the limited detection opportunities associated with the closure of schools and other educational resources, not by a decrease in incidence. Furthermore, a lack of willingness to visit hospitals for issues not related to COVID-19 led to professionals having less ability to keep an eye on children for signs of abuse, resulting in CA being underreported during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Rapp et al., 2021 ).

In examining the rate of CA during COVID-19, several systematic reviews have found mixed results, depending on the data collection method ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Marmor et al., 2021 : Rapp et al., 2021 ). Specifically, studies using police reports and official referrals to child protective services showed an overall decrease in CA, but the reviewed articles using other data collection methods, such as hospital reports, surveys, and calls to helplines, showed a significant increase ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ). The expert opinion articles also indicate an increase in CA and neglect cases ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ). Among the reasons for the discrepancy between expert opinion articles and the actual published data, Abdo et al. (2020) noted that high demand for expert evaluation and follow-up occurred during COVID-19, leading to CA case numbers being overestimated, whereas COVID-19 may not have affected those who were chronically exposed to highly stressful environments and adverse economic conditions.

Contributing factors

In view of the fact that the review studies identified too many factors contributing to increased vulnerability to DV during the pandemic and the social distancing measures, the current systematic meta-review classified the factors based on an ecological framework, one of the most widely used theoretical models in DV research ( Kim, 2021 ). This classification strategy provides a better understanding of DV dynamics on different ecological system levels ( Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ). Based on an ecological model of DV, we analyze it at four levels, namely ontogenetic (i.e., the individual’s development history), microsystem (i.e., the family unit), exosystem (i.e., the formal and informal social structures), and macrosystem (i.e., societal and cultural values and beliefs), and assumes that each of these domains contributes to risk and protective markers ( Kim & Merlo, 2021 ).

Ontogenetic (individuals)

IPV against women—Victimization : Five systematic reviews delineated the sociodemographic characteristics and psychopathological vulnerabilities of female IPV victims ( Bayu, 2020 ; McNeil et al., 2022 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ). There is mounting evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic caused economic instability and worsened gender, sexual orientation, disability, race, and ethnicity inequalities ( Bayu, 2020 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). According to Viero et al. (2021) , women are particularly vulnerable to IPV and have been economically dependent on abusive partners in the wake of the pandemic. As a result of the pandemic, there has been an increase in job losses and unemployment, especially among migrants, women of color, and those with little or no education. Mental health issues and other psychological states, such as stress, anxiety, and depression, were also frequently identified as contributing to female IPV victimization ( Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ). Besides identifying individual contributing factors, systematic reviewers detailed the mechanisms of female IPV victimizations. The COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with measures to restrict contact and movement, can lead to economic and social stresses, which result in alcohol and substance abuse, exacerbating psychopathological conditions that contribute to perpetrators engaging in IPV against women ( Bayu, 2020 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ).

IPV against women—Perpetration : In three systematic reviews, IPV perpetrators’ personal characteristics were examined ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ; Viero et al., 2021 ). Women were at greater risk of becoming IPV victims, whereas men were more frequently reported as perpetrators ( Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ). Aside from the stress of confinement and financial uncertainty, which were also identified as factors contributing to female IPV victimization, gender role attitudes, control desires, and aggressive and controlling behaviors have all been linked to increased IPV perpetration by male partners ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ).

CA—Perpetration : As a result of SAH orders and limited access to teachers, who are mandated reporters, children have been particularly vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Syibulhuda and Ediati’s (2021) systematic review is unique in that it compares risk factors for CA perpetration before and during the pandemic. CA perpetration is still related to socioeconomic conditions and mental health, and this has been the case both prior to and during the pandemic, according to the review results. Childhood experience, however, had only been identified as a risk factor for CA perpetration before the pandemic ( Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ). In another systematic review, Rapp et al. (2021) found that CA perpetration is associated with increased parental stress.

Microsystem (family and relationships)

IPV against women : A systematic review found that forced lockdowns and work-from-home policies affect the dynamics in families, particularly those with middle and low socioeconomic status ( Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ). Families that live in crowded homes and have decreased income are at the greatest risk of stress, anger, frustration, and conflicts within the families ( Bayu, 2020 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; McNeil et al., 2022 ). Apart from these tense family situations, dependence on partners, increased controlling behavior, a lack of assertive communication, and fatigue also contribute to the high rates of IPV against women during a pandemic. In addition, IPV victims are struggling to implement security plans due to the fear of contagion and a lack of social contacts and support around them ( Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ).

CA : In a systematic review by Bayu (2020) , the only one to examine the factors contributing to CA at the microsystem level, staying with an abusive parent during the COVID-19 emergency was found to contribute significantly to the rise in CA. Bayu (2020) further highlighted that children are victims of DV as well if they witness it being perpetrated against an adult in the home.

Exosystem (community)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many DV shelters closed or were converted into health centers ( Bayu, 2020 ). The abusers exploit victims’ inability to ask for help or escape due to this community factor, namely a lack of services and support organizations for DV victims and difficulty in accessing these services, which contributes to high DV rates ( Bayu, 2020 ; Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ). Another exosystem-level risk factor is the lack of mental health services since DV victims exposed to their abusers more often during the pandemic require increased mental health services ( Su et al., 2021 ). In a pandemic, it is crucial not only to increase the number of community services available to DV victims, but also to improve the quality of services. Poor performance in the health sector, including the lack of training given to health professionals in screening and identifying DV cases and a high priority placed on care associated with COVID-19 at the expense of DV intervention, contributed to the high incidence of DV during the pandemic ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ). Living in remote rural areas, as well as facing restrictions on activities or difficulty accessing normal community activities, can further isolate a person and make it harder to seek help, leading to higher DV rates ( Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ).

Macrosystem (culture/laws)

Macrosystem-level risk factors for DV during a pandemic have only been examined in a small number of primary studies. However, systematic reviews have repeatedly stressed their importance as major causes and triggers of DV ( Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ). During a pandemic, a lack of firm policies related to DV matters contributes to a high rate of IPV against women during that pandemic ( Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ). The economy at the national level, however, does not influence DV levels during a pandemic. IPV against women was evident both in economically fragile regions and in economically affluent ones, according to Kourti et al.’s (2021) systematic review. It is important to have social welfare and other policies at the macrosystem level to cushion the negative impacts of the economic crisis caused by COVID-19 ( Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ).

Mitigating policies and practices

Four systematic reviews identified and synthesized the specific multidisciplinary interventions and strategies needed to address DV within the context of COVID-19 ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Su et al., 2021 ). These practical and timely solutions primarily focus on reducing victims’ exposure to abusers and improving their access to services. The two types of platforms available are face-to-face and virtual ad-hoc help-seeking solutions ( Su et al., 2021 ).

Face-to-face help-seeking solutions

In systematic reviews, two main results were presented regarding face-to-face help-seeking programs undertaken during the COVID-19 period when access to help was restricted ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Su et al., 2021 ). First, results indicated that European countries and Canada have more successfully and actively implemented initiatives for communicating the code word (either verbally or in writing) for abused women who cannot access virtual channels ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ). For example, in France, Germany, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands, and Spain, there is a specific code called “Mask 19,” which enables abused women to initiate help-seeking activities. In the UK, “ANI” (which stands for “Action Needed”) allows domestic abuse victims to seek immediate assistance at participating pharmacies, while in France, “Safe Word” emergency alert systems, and in Canada, “The Signal for Help” hand gesture, have been implemented ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Su et al., 2021 ). Also, in the UK, there is a “silent solution” where DV victims can call an emergency line (999), tap their fingers on the phone or cough as an alternative to speaking, and if prompted, can press 55 on the phone to specify an emergency ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ).

Another finding is that community sectors and public places play a crucial role in facilitating help-seeking for women who cannot access virtual resources ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ). In France, Spain, Germany, Italy, Norway, and Argentina, pharmacies and grocery stores have been used to provide essential services, like using confidentiality codes and distributing informative handouts ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ). Postal workers and delivery drivers in the UK have also been asked by the police to watch out for signs of abuse and to notify police and social services on behalf of DV victims ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Su et al., 2021 ).

Virtual help-seeking solutions

Many countries, especially high-income countries such as Norway, Germany, France, Spain, Italy, and Argentina, have promoted virtual help-seeking services to reduce the time and effort DV victims spend seeking help ( Su et al., 2021 ). In particular, DV victim centers have benefited from ad-hoc online help-seeking platforms, which have provided DV victims with a comprehensive set of health and safety resources without the need to search for another website ( Su et al., 2021 ). Shelters, victim support centers, helplines, and police departments have also used virtual channels, such as websites and messaging applications, to maintain contact with DV victims and provide support resources. This has minimized the risk of exposure to COVID-19 and ensured the victim’s privacy and security ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ).

Studies on DV: Emerging issues

In systematic reviews of studies on DV during the COVID-19 pandemic, systematic reviewers have explored and discussed emerging issues ( Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). Three major issues were identified in the current study. Studies of DV often discuss factors contributing to an increase in DV incidence that are specific to COVID-19 ( Nasution & Fitriana, 2020 ). Several factors have consistently been identified as contributing to the surge in DV over the years ( Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ). The roles of COVID-19, however, were interpreted inconsistently. According to Pentaraki and Speake’s (2020) literature analysis, COVID-19 can be viewed as a context that exposes and exacerbates preexisting inequalities or as a cause of DV. Specifically, some researchers have suggested that COVID-19 conditions are merely factors that aggravate or trigger DV instead of causing DV ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). Others, however, argue that DV aggression results from frustration and agitation generated by the COVID-19 context ( Mazza et al., 2020 ). Pentaraki and Speake (2020) warn that this approach risks scapegoating COVID-19 as a cause of DV.

There is also an emerging concern about how useful online support measures have been during the pandemic among DV victims. A systematic review by Pentaraki and Speake (2020) found several articles concluding that providing online support is not appropriate and effective in cases of DV during lockdowns, despite this technique’s popularity. Two reasons lead to this conclusion. On the one hand, the provision of online support can pose risks to DV victims, since the perpetrator may be monitoring online communication channels. In addition, victims may be confined to small spaces and spend more time with the perpetrator, making it difficult to communicate safely and confidentially with virtual support services ( Campbell, 2020 ). It is also unlikely that all women have access to stable internet or can afford communication or broadband technology in some regions of the world due to extreme poverty ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ; Ragavan et al., 2020 ).

The third emerging issue relates to the scope and methodology of DV studies on COVID-19. According to systematic reviews, DV definitions vary greatly between studies, resulting in virtually no generalizable results ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ). Physical and psychological violence are the subjects of most DV studies surrounding COVID-19, and sexual violence and verbal abuse are understudied ( Kourti et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, in light of the study methodologies, DV studies were found to be inconsistent in their study designs and have often relied on administrative data, such as helpline reports. Police reports, surveys, and big data are less commonly used ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Viero et al., 2021 ). Research results regarding changes in DV rates during COVID-19 vary according to the method used to collect data ( Lausi et al., 2021 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ). In general, researchers have faced difficulty conducting rigorous studies on the trends in DV incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Viero et al., 2021 ).

A Synthesis of Policy and Practice Implications

We reviewed the policy and practice implications in the included systematic reviews and identified six recurring themes, including basic and extensive-intensive services, digital equality and alternative avenues to online, intersectional approaches, training and education, multidisciplinary approaches, and collaborations. This section discusses the implications based on these themes.

Both Basic and Extensive-Intensive Services

In addition to operating specialized centers and volunteer initiatives, systematic reviewers have noted the importance of maintaining and providing basic services for DV victims in their community ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ). At a time when women and children needed DV services more than ever during COVID-19, evidence suggests that basic services decreased and were disrupted as resources were diverted to deal with the pandemic ( Bayu, 2020 ). Because of the pandemic’s long-term impact, basic support services and programs must be maintained, expanded, and diversified to prevent DV, ensure the continuity of quality care, identify DV signs, and provide support to DV victims in the event of a pandemic ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ). Among these services are helplines and child protection services ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ). As a way to resolve barriers to help-seeking during the pandemic, such as inadequate information about community-based DV services and concerns about contracting the virus at service points, several authors recommended routine screening for DV during remote primary care consultations ( Bayu, 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ).

The systematic reviewers also called for more comprehensive and intensive services. For screening, identifying, and addressing DV cases throughout and after the COVID-19 pandemic, intensive law enforcement, social services, victim advocacy follow-up, and transitional housing options are vital ( Piquero et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ). Basic as well as extensive-intensive services to DV victims cannot be provided without the government dedicating resources to service providers ( Marmor et al., 2021 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ).

Digital Equality

Since DV facilities have been closed in response to social isolation and regulations of COVID-19, efforts have been made to create and implement online interventions and web-based services to reach out to those women and children at the greatest risk of DV ( Marmor et al., 2021 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ; Viero et al., 2021 ). A few examples are developing apps, expanding remote victim services, and implementing abuse screenings and safety planning through telehealth ( Piquero et al., 2021 ; Viero et al., 2021 ). In fact, a growing body of evidence suggests that technology-based online interventions may benefit DV victims and may result in better outcomes than traditional in-person interventions ( Su et al., 2021 ). Rural areas and poor countries, however, do not have high-speed internet access and DV victims cannot afford technology for communication and broadband. In this context, researchers emphasized the importance of designing and developing online systems that are accessible via low-tech devices ( Su et al., 2021 ). More importantly, the digital divide should be addressed with greater digital equality , along with free or low-cost technology, in an era of rapid advancements in online interventions and web-based services for DV victims during the pandemic, to ensure that no one is left behind ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ).

Community Development

Special attention needs to be paid to DV victims or those at risk with no private space and who are confined with perpetrators because of lockdown measures. For them, seeking online assistance is difficult, and remote support is unsafe ( Bayu, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). There should be alternatives to technology-based online interventions available to this group. Systematic reviewers highlighted the value of community development work and the need to mobilize all sectors of the community to address DV during pandemics ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). As a good example, the use of specific colors or codes to activate the help-seeking process in the community through pharmacies and supermarket chains has been implemented in European countries and Canada during COVID-19 ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Su et al., 2021 ). As part of their intriguing proposal, Su et al. (2021) suggested repurposing hotels for shelter homes during a pandemic. By integrating hotels into a coordinated community response to DV, the massive negative impact of COVID-19 on tourism could be effectively managed. In addition, Su et al. (2021) stressed the importance of places in the community where victims can pack an escape bag or pick up resources, tips, and supplies discreetly if they wish to escape their abusers during a lockdown.

An Intersectional Approach to Marginalized Groups

Both evidence and history support the conclusion that pandemics exacerbate gender and intersectional inequalities, and marginalized groups face additional challenges ( Marmor et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ). In addition, people with mental illness or chronic health conditions, immigrants or refugees, and those living in remote rural areas are some of the groups who are disproportionately isolated during the pandemic ( Piquero et al., 2021 ). It is crucial to understand how a pandemic affects marginalized groups and create policies, plans, and responses that are effective, sensitive, responsive, and equitable ( Bayu, 2020 ). During the COVID-19 pandemic, emergency measures often fail to consider the different needs of marginalized groups ( Bayu, 2020 ).

Systematic reviewers have urged policy responses and resources to address DV, taking into consideration the intersection of families and children’s social identities ( Marmor et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). Other than culturally adapted screening instruments ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ), DV services based on an intersectional approach for marginalized groups have also been proposed ( Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). As an example, Pentaraki and Speake (2020) recommended that governments exclude DV victims from restrictions on movement during lockdowns. Moreover, Pentaraki and Speake (2020) underlined the importance of implementing public policies for DV prevention, protection, investigation, and punishment in remote rural areas.

Training, Education, and Campaign for Health Professionals, Teachers, and the Public

Health professionals have played a crucial role in identifying and managing DV cases during the pandemic. Accordingly, several authors have highlighted the importance of training and education for health professionals, particularly psychiatrists, radiologists, dentists, and maxillofacial surgery teams ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ). A key component of health professional training and education is information about early signs of abuse, technical knowledge, and remote primary care consultations ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ). Cappa and Jijon (2021) also suggested that teachers should be trained on how to recognize signs of CA to stay vigilant.

Systematic reviewers have recommended extending educational efforts to community members ( Su et al., 2021 ). In COVID-19, public campaigns via television or social media, along with informative leaflets and handouts, are considered cost-effective ways to educate the public on available services and new policy initiatives ( Kourti et al., 2021 ). Su et al. (2021) proposed expanding the campaign’s scope to include both DV victims and abusers. Specifically, through integrated campaign interventions, communication and marketing resources need to deliver persuasive messages to DV victims, encouraging them to seek help, as well as educating DV offenders about the laws, regulations, and social consequences associated with DV abuse, which reduces the likelihood of further DV.

Multidisciplinary, Multi-Agency, and Cross-Country Collaborations

According to systematic reviewers, multipronged and multidisciplinary strategies are needed to address DV, both amid and beyond the pandemic, since DV solutions require people and resources from diverse fields, namely healthcare, law enforcement, laws, education, social science, social work, and technology ( Bayu, 2020 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ; Su et al., 2021 ).

Several systematic reviews also emphasize the need for collaboration and integration among different systems and social services when collecting data, selecting indicators, assessing impact, and designing interventions to combat DV ( Marmor et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ).

Specific examples of multi-agency partnerships include collaboration between police and local health protection teams to identify vulnerable women and children through linked datasets ( Viero et al., 2021 ) and team-based response units between COVID-19 testing and vaccination sites, police agencies, and DV response organizations to conduct abuse screenings and safety plans ( Piquero et al., 2021 ).

Furthermore, the systematic literature reviews emphasize the importance of international collaborative effort during a pandemic to develop key recommendations, establish an international protocol, and integrate international assistance into developing countries, and countries where technology-based solutions and legal frameworks are limited, to protect DV victims ( Bayu, 2020 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ). Technology advances have made multilingual experts around the world potential sources of assistance for DV victims. Global organizations and government agencies should therefore implement a system that connects international experts with individuals experiencing or at risk of DV all over the world ( Su et al., 2021 )

A Synthesis of Future Research Implications

Policy implications have been a focus during the systematic reviews related to COVID-19, but some reviews have outlined subject areas that merit more primary research, along with suggestions for research designs. Four recurring themes were identified, including longitudinal research, reliable and valid data, marginalized groups, and international/comparative research.

Longitudinal Research

It is still too early to tell what will happen with the pandemic. In the existing synthesis studies, primary studies were conducted during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic ( Rapp et al., 2021 ). The vast majority of studies investigating DV changes in response to pandemic-related lockdown orders only used short observation periods ( Piquero et al., 2021 ). Although it is evident that the COVID-19 pandemic has created a variety of circumstances that are known to indicate an increase in DV, DV continues to be high globally regardless of whether a pandemic is occurring, and services for DV remain critical regardless of the circumstances ( Cerna-Turoff et al., 2019 ). According to some experts, as people adjust to the new reality and seek assistance, these rates will steadily decline as the pandemic progresses ( Kourti et al., 2021 ). There is currently no way to fully assess the COVID-19 pandemic’s long-term impacts on DV ( Marmor et al., 2021 ; Rapp et al., 2021 ).

Previous studies of natural catastrophes have demonstrated that it takes at least 1 year to confidently conclude that natural disasters cause greater levels and severity of DV than those found in non-disaster settings ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Cerna-Turoff et al., 2019 ). Systematic reviewers have recommended conducting longitudinal studies through ongoing data collection to determine if DV incidence has remained the same or changed over time during and after the pandemic, as well as if risk factors for DV remain similar or change over time ( Piquero et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ; Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ). A comprehensive understanding of pandemic effects and their aftermath requires more well-designed studies published over time with more representative samples ( Abdo et al., 2020 ).

Reliable and Valid Data

Even though a large volume of literature exists on DV during COVID-19, most studies are not data driven, and few rigorous empirical studies estimate DV incidences during COVID-19 ( Abdo et al., 2020 ; Viero et al., 2021 ). According to several systematic reviews, DV data remain limited and of poor quality due to the absence of internationally accepted standards for measuring and producing statistics, as well as selection bias present in police, healthcare, and administrative datasets ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ; Rapp et al., 2021 ). DV cases are defined and handled differently in different countries, states, and even different cities. It is possible that this variability has contributed to different DV reporting rates and incidence rates during COVID-19 ( Rapp et al., 2021 ).

The primary limitation of research conducted during COVID-19, aside from these general concerns about DV data, is the lack of data directly collected from DV victims ( Rapp et al., 2021 ). In part, this is due to social isolation, which makes it difficult to reach out to victims. Victim perspectives are essential to fully understand the nature and context of DV during COVID-19. The systematic reviewers recommend that future research should strive to develop innovative methods for including DV victims as active participants in their studies ( Marmor et al., 2021 ).

DV studies conducted within the COVID-19 context mainly focus on women and children, leaving out other family members ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ). Data were also lacking for DV among men and non-heterosexuals during COVID-19 ( Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020 ; Kourti et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). In directing future research, systematic reviewers have urged the scientific community to use reliable and valid data from multiple sources, including police agencies, shelters, clinical settings, and self-report victimization records so that they could estimate the varying forms of DV against different family members during and after the COVID-19 outbreak ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Piquero et al., 2021 ).

Marginalized Groups

As discussed previously, systematic reviewers have concluded that DV could be effectively addressed by an intersectional approach to prevention, screening, and intervention ( Sánchez et al., 2020 ). There are, however, only a few primary studies included in the existing systematic reviews that examine specific risk factors associated with marginalized groups ( Marmor et al., 2021 ). The cultural and contextual differences, as well as the possible disproportionate effects of the pandemic and restrictions on DV among vulnerable individuals in the community, were often overlooked in studies ( Marmor et al., 2021 ). Specifically, there was a shortage of literature on the current topics pertaining to people of color, the elderly, children, the disabled, the LGBT community, immigrants, asylum seekers, refugees, closed religious communities, and other minorities ( Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ). As recommended by systematic reviewers, future DV research should investigate the moderating effects of cultural, gender, religious, and other social identities on COVID-19/DV relationships, as well as how marginalized groups are affected differently by DV risk and protective factors ( Javed & Mehmood, 2020 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ; Pentaraki & Speake, 2020 ).

International and Comparative Research

The global nature of COVID-19 warrants further international and comparative research on DV ( Rapp et al., 2021 ). It is important to conduct international and comparative research on the pandemic’s impact in different countries that takes into account cultural norms, such as health behaviors, and the intersectionality of social identities, all of which may contribute to the unique combinations of risk factors and protective factors specific populations may experience ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Marmor et al., 2021 ). In addition to providing insights into DV trends during and after the pandemic, an international and comparative approach would allow for fully integrated findings and provide insights into possible imbalances in the pandemic’s effects on DV across different contexts and sectors of society ( Marmor et al., 2021 ).

Systematic reviewers have emphasized the importance of international collaboration to share information about DV during and after the COVID-19 pandemic ( Marmor et al., 2021 ). Additional information on the risk factors associated with DV at the different ecological levels is critically needed ( Dutton, 1995 ). Among the recommended strategies is to establish an international information registry. This registry, together with international data entry standards, will enable cross-country comparisons and generalizations of key findings on DV in pandemic contexts ( Cappa & Jijon, 2021 ; Rapp et al., 2021 ). Developing effective prevention measures will be impossible without these global efforts to accumulate the evidence base ( Marmor et al., 2021 ).

Public health leaders, women’s and children’s groups, and policymakers worldwide have expressed concerns about the pandemic’s potential to cause a spike in DV. The need for a better understanding of DV within the COVID-19 context cannot be overstated ( Piquero et al., 2021 ). To address this need, the present study synthesized 15 systematic review studies published across various disciplines pertaining to DV during the COVID-19 pandemic using a systematic meta-review approach. It is hoped that the findings of this review provide clear insight into current knowledge of prevalence, incidence, and contributing factors, which could help to develop evidence-informed DV prevention and intervention strategies.

Despite its contributions, we must acknowledge two limitations of this study. The first limitation relates to our search strategy. The current systematic meta-review did not search gray literature. Therefore, we cannot guarantee that we located all relevant systematic reviews ( Waller et al., 2021 ). Including detectable gray literature, however, would increase selection bias, since it is impossible to determine the representativeness of gray literature ( Tsuji et al., 2020 ). The quality of gray literature is also a concern, as most gray literature is not peer reviewed ( Pratt, 2010 ). Overall, we believe that ensuring the quality of systematic reviews included and preventing selection bias outweighs the concern about potential publication bias ( Kim, 2022 ; Pratt, 2010 ). Second, we need to recognize the inherent limitation of a systematic meta-review approach with regard to its contents. Because our meta-review relied on systematic reviewers’ work, it is less likely to provide the same level of detail reported in the primary studies ( Kim & Merlo, 2021 ). In other words, synthesizing systematic reviews may inevitably result in information loss as we move from primary studies to systematic reviews and then to the systematic meta-review ( Gibson et al., 2011 ). As a solution to this inherent limitation, we checked the primary studies whenever necessary to identify the details.

Implications for Future Systematic Reviews

The findings section outlines themes that recur in the implications for future primary research that the studies’ systematic reviewers proposed. Here we discuss four areas where systematic reviewers’ attention is warranted.

DV service provision systems : Prior systematic reviews have consistently described primary studies on health sectors in various countries, observing commonalities in the process and roles related to DV intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Kourti et al., 2021 ; Sánchez et al., 2020 ). Comparatively, concerning DV service provision systems, no systematic review exists. Instead, one existing systematic review ( Su et al., 2021 ) briefly summarized the development of DV services provision systems as well as legislation in three example countries (Australia, the UK, and China). According to Su et al. (2021) , Australia and the UK have similar DV service provision systems and adequate DV legislation, but China’s DV service provision systems lack availability, accessibility, and awareness, and their legislation is inadequate ( Su et al., 2021 ).

In the existing systematic reviews, there is very little data available on DV service provision systems, as well as no synthesis of research on the COVID-19 pandemic impact on these systems. There have been few primary studies on this topic, which might explain this ( Garcia et al., 2022 ). Several emerging studies, however, have examined the early-phase impacts of COVID-19 on domestic and family violence service provisions in multiple countries ( Carrington et al., 2021 ; Johnson et al., 2020 ; Murugan et al., 2022 ). These studies explored the views and experiences of service providers and practitioners on how they have adapted to changes in DV service delivery during COVID-19. Examples include studies conducted in Australia ( Carrington et al., 2021 ; Cortis et al., 2021 ; Pfitzner et al., 2021 ), the United States ( Garcia et al., 2022 ; Voth Schrag et al., 2022 ; Wood et al., 2022 ), and the UK ( Riddell & Haighton, 2022 ).

A brief review of the available studies revealed that four major service adaptations and changes have occurred across countries as a result of COVID-19, involving the shift toward remote service provision ( Carrington et al., 2021 ; Cortis et al., 2021 ; Riddell & Haighton, 2022 ; Sapire et al., 2022 ; Voth Schrag et al., 2022 ; Wood et al., 2022 ), a reduction in overall service capacity ( Cortis et al., 2021 ; Wood et al., 2022 ), inter-agency collaborations ( Garcia et al., 2022 ; Murugan et al., 2022 ; Riddell & Haighton, 2022 ), and the provision of limited DV services to historically oppressed or marginalized groups ( Garcia et al., 2022 ; Sapire et al., 2022 ).

These emerging studies also identified the unique characteristics of DV service provision systems and the challenges each country faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. As an example, in Australia, DV services transformed from preventative, early intervention approaches to crisis driven, reactive responses as a result of victims’ isolation with perpetrators ( Cortis et al., 2021 ). In the UK, national initiatives were introduced, while local authorities created their own service specifications. A range of specialist domestic abuse services was also delivered by the voluntary sector organizations ( Riddell & Haighton, 2022 ). In the United States, Sapire et al. (2022) reported that disruptions to gender-based violence services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic compounded long-term policy and funding constraints, leaving DV service providers unprepared for the challenges posed by the pandemic.

Further systematic reviews are needed to fully understand the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on DV service provision systems and policies worldwide ( Garcia et al., 2022 ). Specifically, the similarities and differences among countries in DV service adaptations, modifications to safety plans for survivors undergoing SAH and social distancing orders, and emergency preparedness plans must be identified, documented, and evaluated in systematic reviews. Using information from future systematic reviews, policymakers and service providers can prioritize DV services in emergencies, improve DV service delivery during a pandemic like COVID-19 by addressing barriers, and elevate policies addressing the structural oppressions affecting DV ( Garcia et al., 2022 ; Sapire et al., 2022 ; Wood et al., 2022 ).

Domestic homicide (DH) : The COVID-19 pandemic accompanied by uncertainty and unrest lead to an increase in firearm sales in the United States ( Lynch & Logan, 2022 ; Lyons et al., 2021 ). The link between firearm access and the risk of lethal IPV is well established ( Kaukinen, 2020 ; Wood et al., 2022 ), but little empirical research appears to have been conducted on the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on DH. Lynch and Logan (2022) are among the exceptions. Based on the perception of DV service providers, this study examined gun violence and firearm access in the context of the pandemic. Nearly 30% of respondents reported that firearm-related homicides increased during the pandemic. Their responses, however, were not verified through official data.

While the limited data have been inconsistent outside the United States, reports have emerged of an apparent increase in DH during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through the analysis of newspaper articles, Barchielli et al. (2021) found that the number of women killed in the family/affective sphere in Italy increased by 5% during the COVID-19 lockdown. Furthermore, Bradbury-Jones and Isham (2020) reported in their editorial letter that DH incidences in the UK have increased since lockdown restrictions were implemented. Yet, they cautioned that it was too early to tell whether the increased reporting of these deaths was due to increased media attention or an actual increase in DH rates. Indeed, Stripe (2020) found an increase in the number of DHs recorded by the police in England and Wales in 2020, compared to the same period in 2019, but a slight decline compared to 2018.

Among the most rigorous studies with official data and sophisticated statistical techniques are Asik and Ozen (2020) , which examined the effect of social distancing measures on female homicides in Turkey. Compared to the same period between 2014 and 2019, the probability of a woman being killed by an intimate partner declined by about 57% during the period of strict social distancing measures, and by 83.8% during curfews. Given that most women are killed by ex-partners or by partners they are seeking separation from, Asik and Ozen (2020) suggested that the physical inability of ex-partners to reach the victims, fewer women leaving their current partners due to economic hardships and fears of infection, and/or an increased risk of being caught, may have contributed to the decline in DH. A number of potentially conflicting mechanisms may be at play in the pandemic, leaving questions about how it will affect DH ( Asik & Ozen, 2020 ). Further systematic reviews are needed to identify the prevalence and incidence of DH and to evaluate how country-specific situational factors, like firearm ownership, moderate COVID-19’s effects on DH rates ( Lynch & Logan, 2022 ; Wood et al., 2022 ).

Cases of heterogeneous perpetrators, victims, and circumstances : A variety of factors have contributed to DV vulnerability during the pandemic, according to systematic reviews. However, systematic reviewers have failed to identify and synthesize empirical research findings concerning risk factors specific to each social identity, suggesting that future systematic reviews need to pay particular attention to a heterogeneous group of perpetrators and victims with different social and economic backgrounds.

Existing systematic reviews cannot provide a comprehensive explanation of DV in the context of COVID-19, primarily due to the lack of discussion on macrosystem-level contributing factors. Researchers, especially feminist scholars, have emphasized the need to frame DV research within a social and cultural context encompassing all aspects of macrosystems, particularly the social norms around gender roles and patriarchy ( Malmquist, 2013 ). A macro-level contributory factor must be incorporated into future assessments of DV risks during pandemics ( Scott, 2020 ).

Each country implemented different protection measures at different times and in different ways. It could be helpful to compare the prevalence and patterns between countries with and without specific COVID-19 protection measures to understand the impacts of such measures on family dynamics and DV. In systematic reviews, the vast majority of primary studies included were conducted in developed countries, despite DV being a global issue. The more empirical research is conducted in developing countries, the easier it becomes for systematic reviewers to combine the findings and compare them with those from primary studies in developed countries, ultimately giving us more generalizable findings in the field.

Meta-analysis with an ecological perspective : The current systematic meta-review results suggest that the causes of DVs during COVID-19 may be complicated, and contributing factors may vary based on victim–perpetrator relationships, families, communities, and countries. Since all but one of the systematic reviews in the current study used a descriptive approach, this study was unable to directly compare the relative significance of contributing factors. To expand our knowledge of DV in the context of a pandemic, future systematic review studies need to employ a meta-analytic approach by estimating and comparing the effect sizes of different ecological system levels of risk factors to predict DV perpetration and victimization, which, in turn, can help practitioners identify potential offenders and victims in advance. There may be differences in the relative significance of the factors contributing to DV during the pandemic compared to what they were before ( Syibulhuda & Ediati, 2021 ). The results of a meta-analysis will be useful to fully integrate the findings and identify changes in the contributing factors’ effect sizes before and during the pandemic ( Marmor et al., 2021 ).

DV in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a subject of substantial scholarly inquiry across multiple disciplines. Our systematic meta-review contributes to the DV literature since it provides a more complete picture of DV by synthesizing systematic review results, identifying gaps in research and policies, and recommending future directions. Taken collectively, our findings suggest that DV occurs in a predictable and non-random manner, but within pandemic contexts, it exhibits diverse characteristics and dynamics. A single intervention will not be able to prevent all types of DV victimizations during the pandemic. When researchers and policymakers better understand the nature of DV and types of victimizations, they can allow limited resources to be allocated more efficiently and prevention strategies to be targeted at areas of greatest need. The development of evidence-informed policies, programs, and practices will require more systematic reviews and meta-analyses, especially those that apply the ecological approach as well as the multidisciplinary approach. It is also crucial that the international DV research community collaborates in order to better document, prevent, and address the potential for significant spikes in DV related to pandemics and develop strategies for knowledge dissemination.

Critical Findings:

The research questions most frequently addressed in the DV and COVID-19 systematic reviews included in the current study relate to prevalence and incidence, contributing factors, mitigating policies and practices, and emerging issues in studies on DV in the context of COVID-19.

The recurring themes related to policy and practice implications discussed in systematic reviews included basic and extensive-intensive services, digital equality, community development, an intersectional approach to marginalized groups, training/education/campaign for health professionals, teachers, and the public, and multidisciplinary, multi-agency, and cross-country collaborations.

The recurring themes associated with implications for future primary research discussed in systematic reviews included the need for longitudinal research, reliable and valid data, the sample of marginalized groups, and international and comparative research.

Implications of the Review for Practice, Policy, and Research:

Multipronged and multidisciplinary strategies are needed to address DV, both amid and beyond the pandemic, since DV solutions require people and resources from diverse fields, namely healthcare, law enforcement, laws, education, social science, social work, and technology

Systematic reviewers have recommended conducting longitudinal studies through ongoing data collection to determine if DV incidence has remained the same or changed over time during and after the pandemic, as well as if risk factors for DV remain similar or change over time

Future systematic review studies need to employ a meta-analytic approach by estimating and comparing the effect sizes of different ecological system levels of risk factors to predict DV perpetration and victimization, which, in turn, can help practitioners identify potential offenders and victims in advance.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tva-10.1177_15248380231155530 for Domestic Violence in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Synthesis of Systematic Reviews by Bitna Kim and Meghan Royle in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

Author Biographies

Bitna Kim , Ph.D., is a Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Sam Houston State University. Specific areas of interest include a systemic review and meta-analysis of the risk factors and intervention/programs, multi-agency partnerships, and international/comparative criminology and criminal justice.

Meghan Royle , M.A., is a doctoral student in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Sam Houston State University whose research focuses on health criminology and related constructs. She graduated from the Univesity of Maine in 2019 with a B.S. in biology and from Sam Houston State University in 2021 with an M.A. in criminal justice and criminology.

In this article, the term “domestic violence” (DV) refers to all forms of violence committed within a family or domestic context. The term “intimate partner violence” (IPV) refers to a case of violence against partners, whereas the term “child abuse” (CA) refers to a case of violence against children.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References marked with an asterisk indicate systematic reviews included in the current systematic meta-review.

- *Abdo C., Miranda E. P., Santos C. S., Júnior J. D., Bernardo W. M. (2020). Domestic violence and substance abuse during COVID19: A systematic review. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62, S337–S342 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asik G. A., Ozen E. N. (2020). It take a curfew: The effect of COVID-19 on female homicides (Working Paper No. 1443). The Economic Research Forum. www.erf.org.eg [ Google Scholar ]

- Barchielli B., Baldi M., Paoli E., Roma P., Ferracuti S., Napoli C., Giannini A. M., Lausi G. (2021). When “stay at home” can be dangerous: Data on domestic violence in Italy during COVID-19 lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 8948. 10.3390/ijerph18178948 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Bayu E. K. (2020). The correlates of violence against women and surveillance of novel Coronavirus (COVID -19) pandemic outbreak globally: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 10, 1–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradbury-Jones C., Isham L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2047–2049. 10.1111/jocn.15296 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campbell A. M. (2020). An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports, 2, 100089. 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Cappa C., Jijon I. (2021). COVID-19 and violence against children: A review of early studies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 116, 105053. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carrington K., Morley C., Warren S., Ryan V., Ball M., Clarke J., Vitis L. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Australian domestic and family violence services and their clients. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56, 539–558. 10.1002/ajs4.183 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cerna-Turoff I., Fischer H. -T., Mayhew S., Devries K. (2019). Violence against children and natural disasters: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative evidence. PLoS One, 14(5): e0217719. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217719 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cervero R. M., Gaines J. K. (2015). The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: An updated synthesis of systematic reviews. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 35(2), 131–138. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cortis N., Smyth C., Valentine K., Breckenridge J., Cullen P. (2021). Adapting service delivery during COVID-19: Experiences of domestic violence practitioners. British Journal of Social Work, 51, 1779–1798. 10.1002/ijgo.13285 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dutton D. G. (1995). The domestic assault of women: Psychological and criminal justice perspectives. UBC Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia R., Henderson C., Randell K., Villaveces A., Katz A., Abioye F., DeGue S., Premo K., Miller-Wallfish S., Change J. C., Miller E., Ragavan M .I. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on intimate partner violence advocates and agencies. Journal of Family Violence, 37, 893–906. 10.1007/s10896-021-00337-7 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gibson M., Petticrew M., Bambra C., Sowden A. J., Wright K. E., Whitehead M. (2011). Housing and health inequalities: A synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health & Place, 17(1), 175–185. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jaspers M., Smeulers M., Vermeulen H., Peute L. W. (2011). Effects of clinical decision-support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: A synthesis of high-quality systematic review findings. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 18(3), 327–334. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Javed S., Mehmood Y. (2020). No lockdown for domestic violence during COVID-19: A systematic review for the implication of mental-well being. Life and Science, 1(suppl), 94–99. 10.37185/LnS.1.1.169 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson K., Green L., Volpellier M., Kidenda S., McHale T., Naimer K., Mishori R. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on services for people affected by sexual and gender-based violence. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 150, 285–287. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaukinen C. (2020). When stay-at-home orders leave victims unsafe at home: Exploring the risk and consequences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 668–679. 10.1007/s12103-020-09533-5 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim B. (2021). Partner-killing of men by female intimate partners. In Shackelford Todd K. (Ed), The SAGE handbook of domestic violence (pp. 287–306): Sage. 10.4135/9781529742343.n18 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim B. (2022). Publication bias: A “bird’s-eye view” of meta-analytic practice in criminology and criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Justice, 78, 101878. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101878 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim B., Merlo A. (2021). Domestic homicide: A synthesis of systematic review evidence. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F15248380211043812 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- *Kourti A., Stavridou A., Panagouli E., Psaltopoulou T., Spiliopoulou C., Tsolia M., Sergentanis T. N., Tsitsika A. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. Advance online publication. 10.1177/15248380211038690 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]