- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

New South Wales

Western australia, other discoveries, immigration boom, life and lawlessness on the goldfields.

Australian gold rushes

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- History Today - The Australian Gold Rush Begins

- kidcyber - Gold Rush in Australia: About Life on the Goldfields from 1851

- State Library of New South Wales - Eureka! The Rush for Gold

- National Museum of Australia - Gold Rushes

- Australian gold rushes - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Australian gold rushes - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The discovery of gold in New South Wales in 1851 began the first of a series of gold rushes in colonial Australia—a defining era of its history. The gold rushes transformed the colonies and shaped Australia’s population and society as the lure of gold attracted miners, known as diggers, from all over the world. The resultant demographic changes, associated economic upheavals, and subsequent development of often rural areas left an indelible mark on the development of the region.

- California Gold Rush (1848–59)

- Cariboo Gold Rush (1860–63)

- Klondike Gold Rush (1896–99)

Gold discoveries

In the 1840s prominent Scottish geologist Roderick Murchison predicted that New South Wales had economically significant deposits of gold. Although his theory soon proved correct, colonial governors kept the early discoveries quiet. The territory had been founded as a penal settlement, and the government feared that news of a gold discovery would lead to an increase in crime or even a convict uprising amongst the miscreant population. Officials were also concerned about the potential economic effects of gold discoveries on agricultural products, which were the colony’s major exports. Specifically, they sought to protect the struggling pastoral industry from a sudden loss of workers in search of riches, and thus suppressed early news of gold.

It was against this backdrop that the earliest known payable gold found in Australia was discovered in New South Wales in 1847 by William Tipple Smith, a mineralogist who had read Murchison’s predictions. Smith sent his first gold sample, taken from the western slopes of the Blue Mountains near the town of Bathurst to Murchison. Murchison notified the colonial government, which declined to take action. The following year Smith found more gold in the Bathurst region. Hoping for a reward that would help offset the costs of his expedition, Smith offered to share the location of the goldfield with government officials, but they declined to pay him. Smith was largely forgotten to history until the late 20th century, when a historian found letters documenting his gold discoveries.

Shortly thereafter, however, the New South Wales government changed its attitude toward gold prospecting after thousands of Australians left the colony for the California Gold Rush of 1849. The exodus caused labor shortages and an economic downturn, and, desperate to revive the economy, the government offered a reward for the discovery of commercial quantities of gold within its borders.

The government having ignored Smith’s discovery, Edward Hammond Hargraves was widely credited as the first person to find payable gold in Australia. Originally from England , Hargraves had been one of the many New South Welshmen to join the California Gold Rush. Although he found no gold in North America , he keenly noticed similarities in the geography of California’s goldfields and the landscape near Bathurst and became convinced that the area housed gold. Upon returning to Australia, Hargraves assembled a team of miners consisting of John Lister and three brothers, William, James, and Henry Tom, and taught them how to pan . He also showed them how to build a rocker, or cradle , to more quickly separate gold from other minerals. On February 12, 1851, Hargraves discovered flecks of gold in Lewis Ponds Creek, and Lister and the Tom brothers soon made larger finds of gold nuggets . Claiming to have found the nuggets himself, Hargraves kept the entirety of the government reward and named the area Ophir , after the biblical city of gold. (Lister and the Tom brothers were finally given credit as the real discoverers of the gold in 1890.)

An account of the discovery was published in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1851, and the news quickly spread worldwide. Within a week more than 400 people had arrived to dig in the area, and the first Australian gold rush was underway. In the year following the Bathurst discovery, around 370,000 immigrants arrived in Australia to seek their fortunes on the goldfields.

The New South Wales gold rush generated an economic slump in the newly formed colony of Victoria as thousands of workers deserted farms and industries to head north to the Bathurst goldfields. In response, the Victorian government quickly formed a gold discovery committee and offered its own reward to anyone who found gold within 200 miles (320 kilometers) of Melbourne .

Although Australian Aboriginal peoples and white settlers had previously found gold in the region, the first official discovery was credited to James Esmond, who found gold near the town of Clunes in June 1851 and sparked the Victorian gold rush. Two months later, in August 1851, James Regan and John Dunlop discovered gold in Ballarat , at Poverty Point, and the site would become the most productive alluvial goldfield in the world at that time. Other discoveries followed at Castlemaine , Daylesford, Creswick, Maryborough , Bendigo , and McIvor. Victoria’s deposits were so rich that the colony accounted for more than one-third of the world’s gold production during the 1850s.

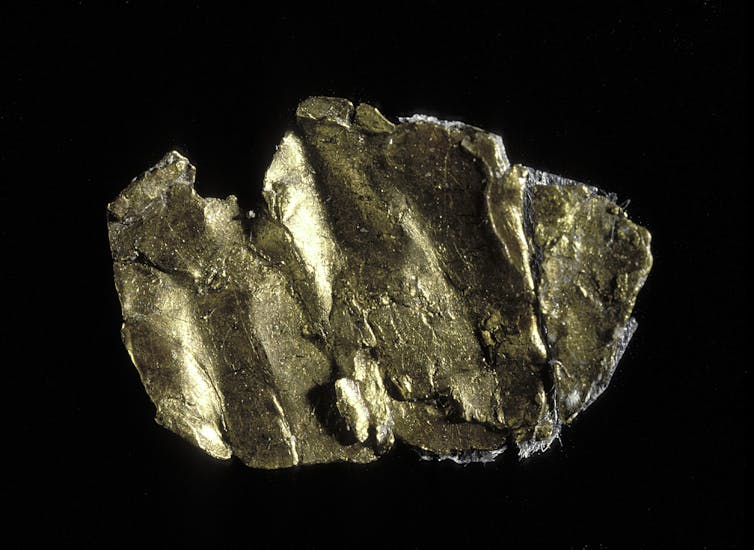

On February 5, 1869, miners found the “Welcome Stranger” nugget near the town of Dunolly, north of Ballarat. It remains the largest alluvial gold nugget ever found, weighing about 159 pounds (72 kg).

Queensland was the next colony to join the gold frenzy. In the mid-1850s, when Queensland was still part of New South Wales, the colonial government encouraged the search for gold on the northern frontier with the hopes that a discovery there would attract white settlers from the south. Although Capt. Maurice O’Connell, the leader of a government settlement at Gladstone , reported “very promising prospects of gold” in 1857, it was a discovery made a year later that sparked the first Queensland gold rush. A prospector named Chapple found gold at Canoona, near Rockhampton , in July or August 1858, and by the end of the year some 15,000 hopeful miners had arrived. The Canoona deposits were small, however, and most of the prospectors were disappointed.

Queensland achieved political separation from New South Wales in 1859, and the new colony’s first major gold find came almost a decade later. In 1867 James Nash discovered gold in the small agricultural town of Gympie , about 90 miles (145 km) north of Brisbane . The find marked the start of the Gympie gold rush, and within months 25,000 people came to the area to try their luck. The influx of miners gave a much-needed boost to the struggling economy of the young colony.

Later discoveries sparked other gold rushes in Queensland. In late 1871 an Australian Aboriginal boy, Jupiter Mosman, found gold in a stream in the northeast. The town of Charters Towers was founded at the site, and miners flooded in. The population reached a peak of 30,000 during the gold rush of the 1870s and ’80s.

Farther north, a find along the Palmer River pulled miners to the frontier in the mid-1870s. Then, in 1882, Edwin and Thomas Morgan made one of Australia’s most important gold strikes at a site known as Ironstone Mountain, near Rockhampton . The brothers renamed the mountain Mount Morgan after themselves, and the so-called “mountain of gold” would become one of Queensland’s richest and longest surviving gold mines. Work would continue at the site until 1981.

The development of Western Australia lagged behind that of the eastern colonies for most of the 19th century, in part because of the apparent paucity of mineral resources. Its fortunes began to change when gold was discovered in the 1880s. A short-lived rush to the Kimberley district in 1886 was followed by more promising finds in the Pilbara and Yilgarn districts in 1887–88. The next important discovery was made along the Murchison River in 1891.

The Murchison gold rush was soon followed by Western Australia’s two most celebrated finds. In 1892 Arthur Bayley and William Ford struck gold in the south at a site called Fly Flat , which was soon renamed Coolgardie. Then, in 1893, a prospector named Paddy Hannan, working with Tom Flanagan and Daniel Shea, discovered gold at a site 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Coolgardie. The main deposit of deep rich ores came to be known as the Golden Mile reef, and the area developed as Hannan’s Find . The town that grew there was named Kalgoorlie.

The goldfields of Western Australia posed great challenges for diggers. The harsh desert landscape heightened the risk of disease, dehydration , and heatstroke , and many miners died. Nevertheless, the western gold discoveries brought a flood of migrants from the eastern colonies who eagerly crossed the continent to escape the economic depressions then occurring in New South Wales and Victoria. During the 1890s the population of Western Australia quadrupled, reaching nearly 180,000 in 1900.

Gold was also discovered at other sites in Australia. South Australia experienced its first gold rush after a discovery at Echunga in 1852. In the Northern Territory workers digging during construction of the Overland Telegraph line in 1871 found traces of gold in the stony hills around Pine Creek, south of Darwin . Gold prospectors began arriving through Port Darwin in 1872. In Tasmania gold finds at a number of sites, including Lefroy in 1869, drew hopeful diggers. However, the quantities of gold unearthed at these sites were much smaller than those in the eastern states and Western Australia, so the gold rushes were smaller as well.

The gold rushes had an immense impact on Australia’s population. News of the 1851 discoveries attracted people from countries around the world, and immigration quadrupled Australia’s population in just two decades, exploding from 438,000 in 1851 to 1.7 million in 1871. As the population expanded, it also began to diversify. Other than the Australian Aboriginal peoples , the colonial population before the gold rushes consisted almost entirely of people from the British Isles . Although the majority of the new immigrants also came from the United Kingdom , they were joined by prospectors from the United States , Germany , France , Italy , Poland , Hungary , and other countries. The gold rush era was also the first time that Australia experienced a significant influx of Chinese immigrants. By 1861 more than 38,000 Chinese people lived in Australia, making up more than 3 percent of the population. More than 12,000 Chinese immigrants arrived in the year 1856 alone.

Chinese prospectors experienced much hardship, racism , and mistreatment on the Australian goldfields. Most were under contract to Chinese and foreign businessmen. In exchange for their passage to Australia, they had to work until they paid off their debt and could then return to China. The Chinese diggers were particularly hardworking and efficient, and unlike white miners, who worked alone or in small groups, the Chinese prospectors worked together in teams of 30 to 100 miners. They preferred to rework claims that had been abandoned by other miners rather than exploring new ground, and thus often found gold that others had overlooked.

The increasing presence of Chinese prospectors was accompanied by a rise in xenophobia by white Australian, European, and American diggers. Strong anti-Chinese sentiment arose on the goldfields throughout the Australian gold rushes, and many racially fueled riots erupted. Some of the most violent riots took place at Lambing Flat (now known as Young) in New South Wales in 1860–61. In the last of these disturbances, on June 30, 1861, some 3,000 Australian, European, and American miners attacked a Chinese camp. They beat the Chinese prospectors, burned their tents, and cut off their queues (traditional long hair braids). In a misdirected response to the riots, the New South Wales government passed the Chinese Immigration Act to greatly reduce Chinese migration to the colony. Similar restrictions had already been introduced in Victoria (1855), South Australia (1857), and would soon follow in Queensland (1877) and Western Australia (1886).

Despite the hatred they endured, some Chinese immigrants were able to find success in the goldfields and also beyond them. Early miners were initially prohibited from planting vegetable gardens in an attempt to discourage the establishment of permanent homes, but the Victorian government began to allow vegetable gardening on the goldfields in 1853. The change was a boon to many Chinese immigrants, who soon played a vital role in supplying fresh vegetables to the often undernourished diggers. As the gold supply started to decline, many of these Chinese agriculturists—perhaps the majority of whom had been farmers in southern China—turned permanently to market gardening, putting their knowledge and skills to work. Many became successful business owners and profited more from providing fresh food for the growing settlements than from searching for dwindling gold deposits.

Living conditions on the goldfields were harsh, and hopeful prospectors faced many hardships. To reach the rural goldfields, prospectors usually had to travel long distances on foot because horse transportation was costly. Most lived in simple tents until they could establish more permanent huts. Neither tents nor huts offered much protection from heat, snakes , or thieves, and disease, accidents, and crime were rampant in many places. In the town of Ballarat alone, in 1859 an average of one miner each week was killed in an accident.

Given that only a small number of the many thousands of hopeful diggers ever struck gold, some frustrated prospectors turned to crime as their dreams of riches faded. Claim jumping—taking someone else’s claim (parcel of land to mine)—was common, and disputes often turned violent. Many diggers armed themselves to protect themselves and their claims.

The gold rushes also attracted men who planned from the outset to make a fortune without digging for gold at all. Bandits known as bushrangers often attacked and robbed miners traveling between goldfields, taking advantage of the fact that successful diggers had to carry their gold with them and were easy targets in the isolated bush. As skilled horsemen and gunslingers with excellent knowledge of the land, bushrangers were a formidable challenge to vulnerable prospectors.

Without police, judges, or other authorities to keep order, the earliest miners had to work out a system of law and order for themselves. Groups of miners established courts to put accused criminals on trial and to hand out punishments to those found guilty. This makeshift system was eventually supplemented by efforts of the colonial governments. Officials in New South Wales and Victoria, for example, appointed a gold commissioner with troopers (mounted police) and foot police (known by the miners as “joes” or “traps”) to oversee each goldfield. With many police officers having left their jobs to join the gold seekers, colonial governments in the early gold rush years relied on the Native Police, a force made up Aboriginal men whose close knowledge of the land helped them to track bushrangers and other criminals. To supplement this force, however, governments had little choice but to accept anyone who was willing to join the police, including formerly incarcerated individuals and many young, inexperienced recruits.

The gold commissioners regulated the goldfields and resolved disputes between miners. They also offered a service designed to move gold securely from the fields to cities for safekeeping. For a fee, diggers could turn over their gold and have it transported on heavily guarded coaches. The “gold escorts” carried thousands of pounds of gold from remote goldfields to Sydney , Melbourne , and other cities each week. While the gold escorts provided some security, they were also a lucrative target for bushranger attacks.

The most famous gold escort robbery took place in New South Wales on June 15, 1862. Frank Gardiner and his gang, which included Ben Hall and John Gilbert, held up a coach at Eugowra as it was traveling from Forbes to Orange . The bushrangers escaped with £14,000 in gold and banknotes, an enormous sum. Gardiner was arrested two years later and spent 10 years in prison for the Eugowra robbery. Other famous bushrangers of the gold rush era included Andrew George Scott (known as “Captain Moonlite”), Frederick Ward (“Captain Thunderbolt”), the Clarke brothers, and Ned Kelly .

To cover the costs of maintaining law and order on the goldfields, the governments of New South Wales and Victoria introduced a license system. Every miner had to pay a high fee—30 shillings a month—for a license, even if they did not find gold. The license had to be carried at all times, and a miner who failed to show one could be fined or arrested. The police charged with enforcing the license system were notorious for corruption and for their brutal methods. Miners also resented that they could not vote and that they had no representatives in the government. For all these reasons, miners reacted to the license requirement with considerable anger.

Opposition to the license system reached its height at Ballarat in 1854, in what became known as the Eureka Stockade or the Eureka Rebellion. Diggers formed the Ballarat Reform League and petitioned the government for change. When their demands were refused, they formed military companies, marched to the Eureka goldfield, and built a stockade. On December 3, 1854, police and military troops attacked the stockade and defeated the diggers, killing more than 20 of them. In the aftermath of the rebellion, however, the government met most of the diggers’ demands. The Victorian government replaced the license requirement with a fairer system in which miners paid a tax on gold they found instead of paying whether they found gold or not. Diggers were also given the right to vote and representation in the Victorian legislature. The Eureka Stockade proved to be a defining moment in the development of Australian democracy .

The gold rushes of the 19th century had profound social, political, and economic effects on Australia. The gold rushes spurred the exploration and settlement of remote lands, pushing the frontier in Queensland and Western Australia in particular. The immigration boom led to a dramatic increase in population and began to diversify the colonies’ predominantly British and Australian Aboriginal society. While some foreign immigrants returned to their homelands, others stayed permanently and some went on to become prominent in business, law, or politics.

The economic boost brought on by the gold discoveries was crucial in the modernization of colonial Australia. During the 1850s the colonies accounted for more than 40 percent of the world’s gold production. This rapid rise catapulted Australia onto the international stage and helped create a wealthy society with one of the highest standards of living in the world at the time. Gold profits were used to establish towns and to transform existing cities with new banks, stores, hotels, and other businesses. The flood of miners and money into Victoria made Melbourne a boomtown and the continent’s largest city. Rural industries expanded as well, as pastoralists increased production of meat and hides to meet the demand of growing cities. The gold rush era also saw large investments in transportation, with the construction of roads, railways , and bridges to move people to and from goldfields and cities.

The impact on the political development of Australia was long lasting. The Eureka Stockade was a catalyst for change, and people started to demand democratic reforms. This movement was also encouraged by new immigrants who brought with them ideas of democracy and equality from Europe and the United States. The calls for reform began to yield results in 1856, when South Australia gave all adult males the right to vote and South Australia and Victoria introduced the secret ballot . Just 50 years after the fateful find at Bathurst, the British colonies would unite to become the independent Commonwealth of Australia.

Not all Australians shared equally in the progress of the gold rush era, however. The anti-Chinese sentiment that took root on the goldfields in the 1850s continued to build as new Chinese businesses and communities thrived. European colonists resented what they perceived as economic competition. Their anger would eventually be embodied in the White Australia Policy of 1901, which severely limited Chinese immigration to Australia for more than 50 years.

Some Australian Aboriginal people found economic opportunities during the gold rushes. They sold food and clothes to the diggers, and some found their own gold and used it for trade. The Native Police were important to the safety of countless diggers, and others played a valuable role as guides and trackers for the white, foreign prospectors who knew nothing of the land. In the end, however, the gold rushes mostly just added to the challenges that Australian Aboriginal peoples had been facing since European colonization began. The miners invaded their lands, caused great environmental damage, and generally disrupted traditional Aboriginal ways of life.

How Did the Gold Rushes Change Colonial Australia? Essay

In the history of nations that throve on the territories of North America and Australia, the nineteenth century is marked by a series of gold rushes that forever changed the ways of development in economical as well as political and social spheres.

Although in Australia minor gold deposits had been discovered already in early nineteenth century, it was only in the 1850s that mass hysteria and search for gold started, acquiring the name of the Victorian gold rush, after the state most abundant in gold. The events connected with the Victorian gold rush transformed colonial Australia by dramatically increasing its population, restructuring the economic system, and promoting a new sense of identity among the nation.

The first and the most obvious transformation Australia underwent as a result of the 1850s gold rush was the immense growth of the population quantity due to immigration rates. Rumors of Australian gold spread in the twinkling of an eye, and the white Australian population which had comprised only 77 thousand people before 1851, rapidly increased by over 370 thousand in only the first year of the rush and constituted 540 thousand people by 1854 (Gold Oz, n. d.).

More settlers arrived to Australia in the several beginning years of the Victorian gold rush than there were prisoners brought to the continent from Britain. By the year 1871, Australian population had trebled from 430,000 in 1851 to 1.7 million in 1871 (Australian Government Culture Portal, 2007). Such dramatic increase in population quantity had its consequences both for the economic and political life of Australia.

Large-scale immigration brought about the ever-growing need of Australian population for developing agriculture, manufacturing, and construction industries.

On the other hand, those industries faced hard times due to the fact that laborers fled to the areas where gold was discovered and thus left their work unattended. Agriculture was in fact one of the spheres most negatively affected by the events of the Victorian gold rush. For one thing, tillers inspired by perspectives of fast enrichment, left their farms behind, abandoning the land for the sake of gold mining.

Other farmers switched their production from wheat to meat and tallow, which were more in demand in the domestic market (Attard, 2008). For another thing, sheep wool which had been Australia’s major export product in the first half of the nineteenth century, was replaced by gold, since the latter appeared a more attractive and valuable source of enrichment for the British Empire (Attard, 2008).

In reply to the incredible wealth shipped by Australia, the country profited from a large amount of imports and business investment to it (Gold Oz, n. d.). The two major states where the largest deposits of gold had been discovered, Victoria and New South Wales enjoyed an improved system of transportation with the building of the first railroad, and the rudimentary mining techniques were quickly optimized to more modern capital-intensive forms of gold-mining by large companies (Cultural Heritage Unit, 2010).

Together with economic benefits, Australian gold rush brought about a number of serious developmental issues to the country. With the land overcrowded by hundreds of thousands of new migrants, it was vital to provide people with appropriate living conditions.

For this purpose, large-scale building projects were launched that satisfied the need for housing for the generation of the gold-diggers and their children later on, in the 1880s. The impulse in technology given by the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s helped Australia survive the severe economic depression of the late nineteenth century (Attard, 2008).

Simultaneously with economic development, population expansion during the gold rush inspired major social and political changes in the nineteenth-century Australia. The people who arrived to the country were no more exclusively criminals. Rather, the colony was seen as a land of new opportunities, and therefore the practice of providing criminals with a free ticket to wealth was ceased. Not only the British, but also German, French, Italian, and even American people came to seek luck in the gold mines of Australia (Gold Oz, n. d.).

This turned the country into a multinational ‘melting pot’ distinguished by diversity of men united by a common ambitious idea of coining their own happiness. Huge masses of people demanded new way of organization and government that would correspond to the newly-arisen sense of being in control of their own destiny and building a self-governed democratic state.

Principles of fair treatment and camaraderie led the new Australians to forming small mining clans which in the 1852 Eureka Stockade won the case against unfair mining licensing system. Two years later, another major rebellion resulted in giving the right to vote to the miners, providing more opportunities for buying land, and reforming the administration of goldfields (Gold Oz, n.d.). These events marked the birth of Australian democracy.

Australian gold rush of the nineteenth century proved to provide a major impulse for developments both in economic and social spheres of the country. The drastic increase in population caused by mass immigration of the 1850s spurred not only technological innovations but also the establishments of democracy in the land that is now known for unprecedented cooperation and mutual support among its citizens.

Reference List

Attard, Bernard. 2008. “ The Economic History of Australia from 1788: An Introduction ”. EH.Net Encyclopedia , edited by Robert Whaples. Web.

Australian Government Culture Portal. 2007. The Australian Gold Rush . Web.

Cultural Heritage Unit. 2010. Electronic Encyclopedia of Gold in Australia . Web.

Gold Oz. n. d. The History of Gold in Australia . Web.

- The Impact of Racial Thought on the Aboriginal People in Relation to Australian History

- Australian Law and Native Title

- The San Francisco Committee of Vigilance

- The California Gold Rush' History

- California Culture During the Gold Rush

- The Merits and Pitfalls of Using Memoir or Biography as Evidence for Past Events

- Imperialism and Modernization

- The Protestant Church Reformation

- Battles and Wars Through the History

- Australian Aborigines Genocide

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, February 7). How Did the Gold Rushes Change Colonial Australia? https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-did-the-gold-rushes-change-colonial-australia/

"How Did the Gold Rushes Change Colonial Australia?" IvyPanda , 7 Feb. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/how-did-the-gold-rushes-change-colonial-australia/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'How Did the Gold Rushes Change Colonial Australia'. 7 February.

IvyPanda . 2019. "How Did the Gold Rushes Change Colonial Australia?" February 7, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-did-the-gold-rushes-change-colonial-australia/.

1. IvyPanda . "How Did the Gold Rushes Change Colonial Australia?" February 7, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-did-the-gold-rushes-change-colonial-australia/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "How Did the Gold Rushes Change Colonial Australia?" February 7, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-did-the-gold-rushes-change-colonial-australia/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

HISTORIC ARTICLE

Feb 12, 1851 ce: australian gold rush begins.

On February 12, 1851, the Australian Gold Rush began in New South Wales, Australia.

Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, World History

Loading ...

On February 12, 1851, a prospector discovered flecks of gold in a waterhole near Bathurst, New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Soon, even more gold was discovered in what would become the neighboring state of Victoria. This began the Australian Gold Rush, which had a profound impact on the country’s national identity . Within a year, more than 500,000 people (nicknamed “diggers”) rushed to the gold fields of Australia. Most of these immigrants were British, but many prospectors from the United States , Germany, Poland, and China also settled in NSW and Victoria. Even more immigrants arrived from other parts of Australia. Wages in the region doubled, but it was still difficult to find workers as people abandoned their stable jobs to seek their fortune in the gold fields . These “diggers” forged a strong, unified identity independent of colonial British authority . This concept of “mateship . . . [has] been central to the way [Australian] history has been told,” according to the Australian government.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 1, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- Free general admission

Gold rushes

1851: Gold rushes in New South Wales and Victoria begin

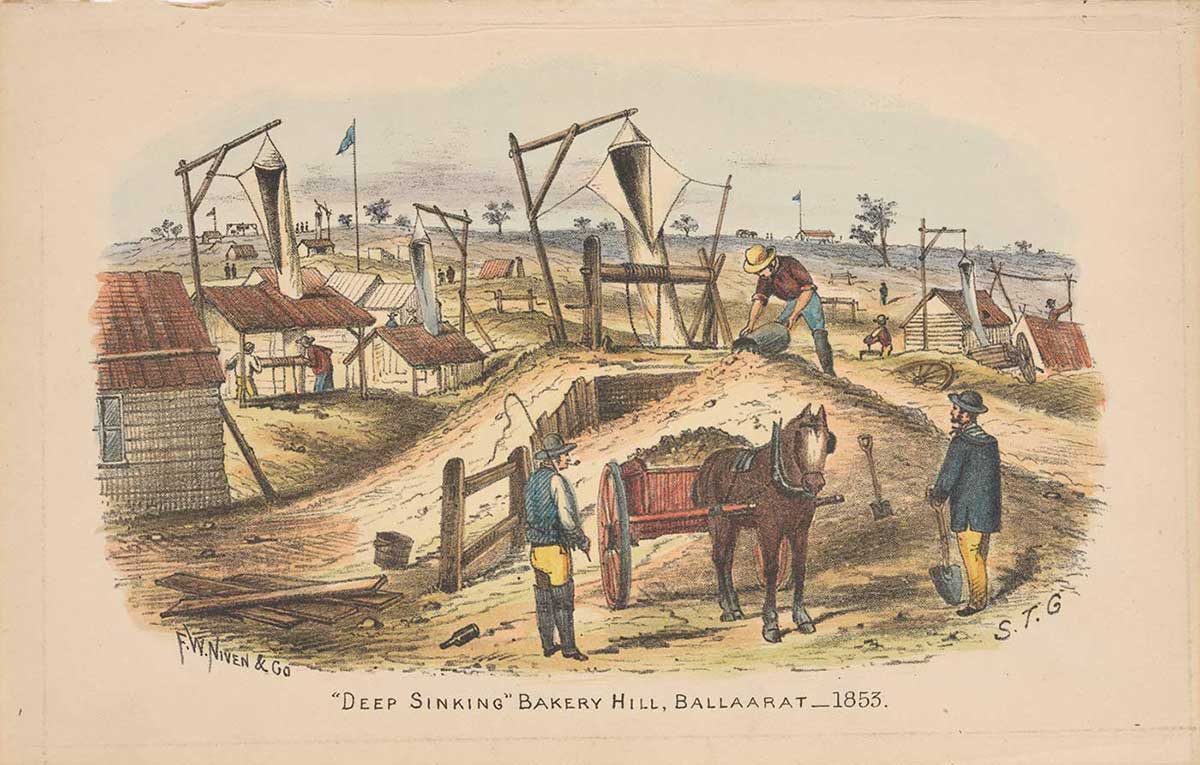

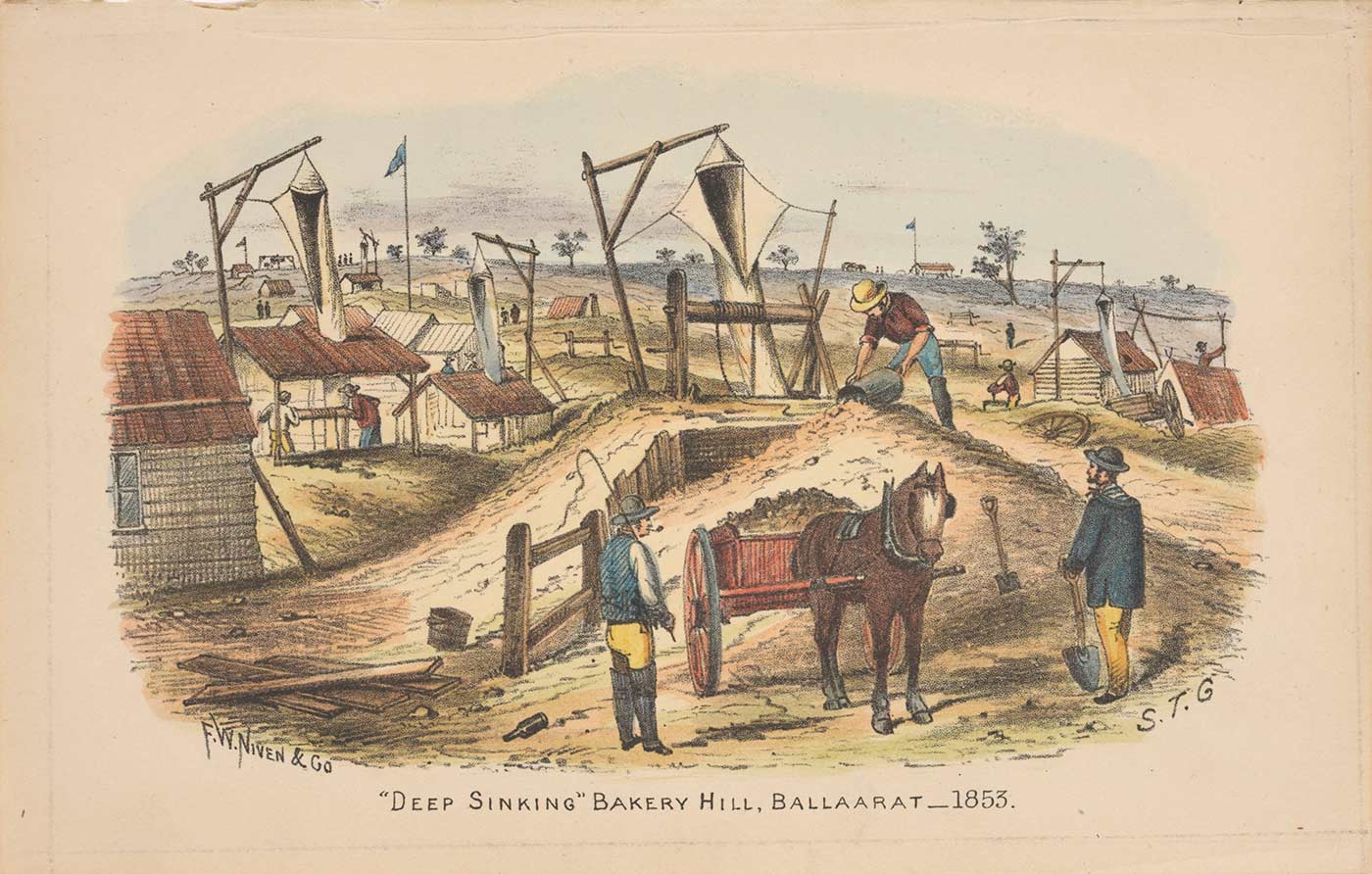

‘Deep Sinking’, Bakery Hill, Ballarat, 1853 , ST Gill. National Museum of Australia

The discovery of gold in the 1850s started a series of rushes that transformed the Australian colonies.

The first discoveries of payable gold were at Ophir in New South Wales and then at Ballarat and Bendigo Creek in Victoria.

In 1851 gold-seekers from around the world began pouring into the colonies, changing the course of Australian history.

The gold rushes greatly expanded Australia’s population, boosted its economy, and led to the emergence of a new national identity.

Geelong Advertiser , 14 October 1851:

There are, we should say, about a thousand cradles at work, within a mile of the Golden Point, at Ballarat. There are about fifty near the Black Hill, about a mile and a half distant, and at the Brown Hill Diggings there are about three or four hundred more; to say nothing of hundreds on the ground not yet set at work. Allowing five for each cradle, the population within a radius of five miles must be a population of about seven thousand men.

The gold rush in live-sketch animation, as told by historian David Hunt

Gold mining cradle. National Museum of Australia

Discovery of gold in Australia

There had been multiple gold finds in New South Wales (Bathurst and Monaro), Tasmania and what would become Victoria prior to the ‘official’ discovery of the precious metal by Edward Hargraves near Orange in 1851.

In 1841 Reverend William Branwhite Clarke, one of the earliest geologists in the colony, came across particles of gold near Hartley in the Blue Mountains.

In 1844 he mentioned it to Governor Gipps who reportedly said: ‘Put it away Mr Clarke or we shall all have our throats cut’.

Gipps feared that mutiny would result if the people of New South Wales, the majority of whom were convicts or ex-convicts, found that gold was within easy reach.

In 1848 mineralogist William Tipple Smith found gold near Bathurst and the following year revealed the find to the NSW Colonial Secretary Edward Thomson. Research by one of Smith's relatives, Lynette Silver, established that Smith’s find was the first discovery of payable gold. However, he was denied the recognition and monetary reward, which was ultimately claimed by Edward Hargraves.

The government’s attitude to gold discoveries changed in 1848 with news of the California gold rush. The promise of fortunes to be had across the Pacific led thousands of men to leave the colony, creating labour shortages and economic depression.

Governor Charles FitzRoy had heard rumours of the gold to be found in New South Wales and believed a mineral discovery in the colony could reverse the economic downturn.

He convinced the British Government in 1849 to appoint a government geologist, Samuel Stutchbury, and offered a reward to anyone who found a commercially viable amount of gold.

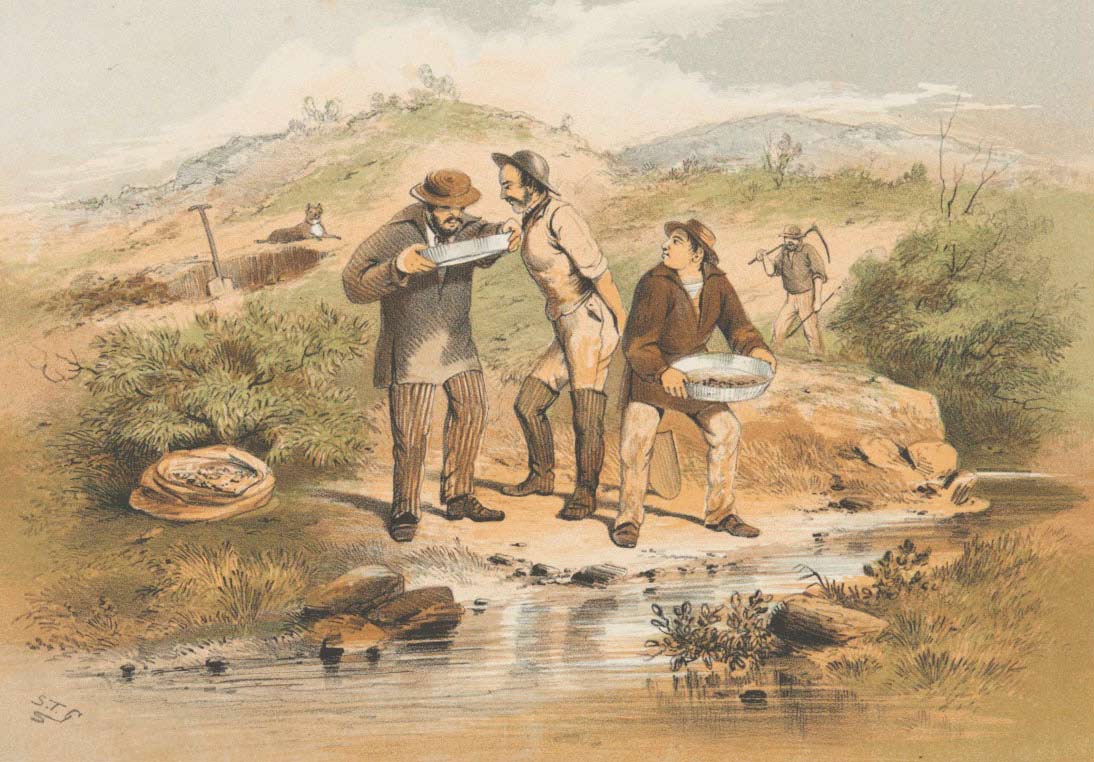

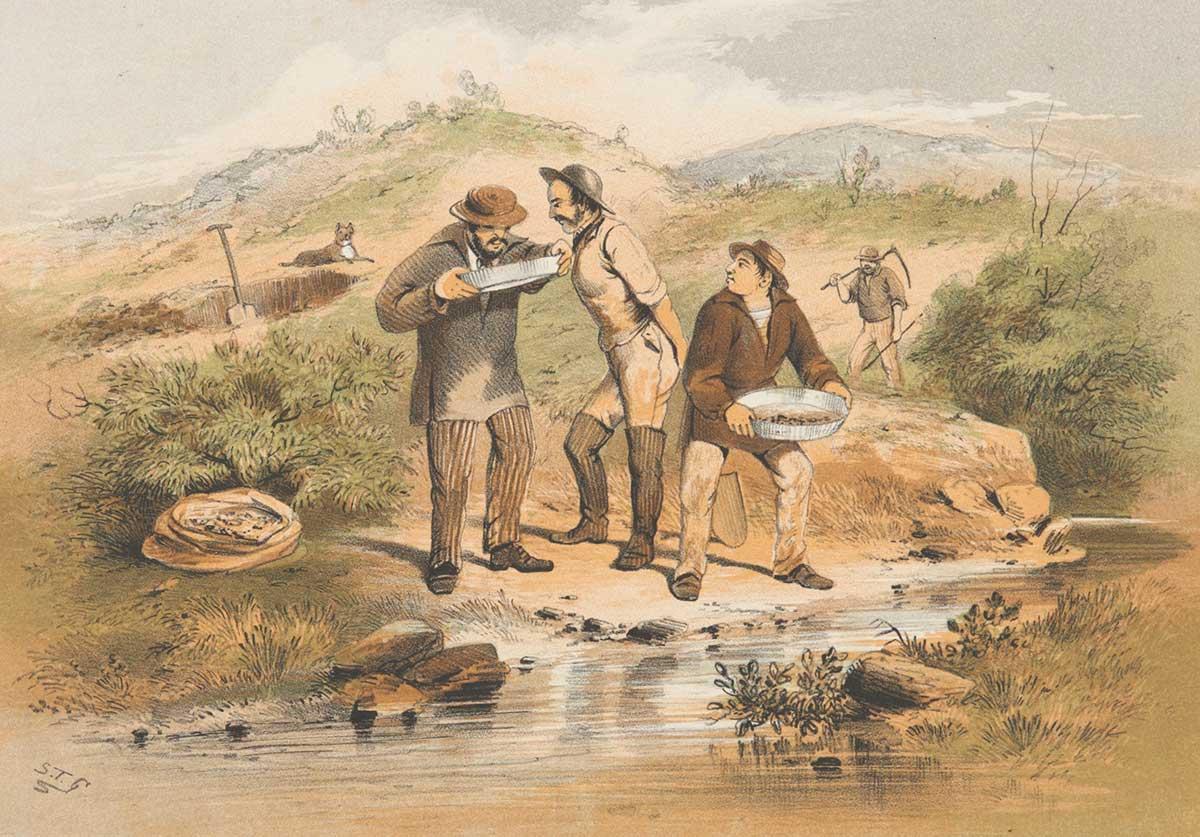

'Prospectors' by ST Gill. National Museum of Australia

Mr E.H. Hargraves, the Gold Discoverer of Australia, Feb 12th 1851 Returning the Salute of the Gold Miners , TT Balcombe, 1875. State Library of New South Wales

Edward Hargraves

Edward Hargraves was a jack of all trades: farmer, storekeeper, publican, pearl-sheller and sailor. In 1849 he sailed for the Californian gold rush.

He failed to find his fortune but was struck by the topographical and geological similarities between California and the interior of New South Wales.

In January 1851 he returned to the colony and immediately headed inland, convinced he would find gold and, more importantly, claim the government reward.

New South Wales gold rush

Near Bathurst, Hargraves enlisted the support of John Lister and brothers William and James Tom. Within weeks they had discovered a small amount of gold at a site Hargraves named Ophir, after a port city of great wealth mentioned in the Old Testament.

Hargraves returned to Sydney in March 1851 and presented his samples to the government. Samuel Stutchbury was sent to confirm the strike, which he did.

Hargraves was eventually awarded the £10,000 prize, which he refused to share with Lister or the Tom brothers.

News of the find was promptly published in the Sydney Morning Herald and by 15 May 1851, 300 diggers had arrived in Ophir. The rush was on.

Gold Washing. Fitzroy Bar, Ophir Diggings, 1851 , George Angas. National Museum of Australia

Gold Washing. Fitzroy Bar, Ophir Diggings, 1851 by George Angas

Victorian gold rush

In the newly established colony of Victoria, men began to flood north to the New South Wales goldfields. The Victorian Government responded with the offer of a reward of £200 to anyone finding gold within 200 miles of Melbourne. Within six months, gold was discovered in Clunes, and then Ballarat, Castlemaine and Bendigo.

The Victorian rush would dwarf the finds in New South Wales, accounting for more than a third of the world’s gold production in the 1850s.

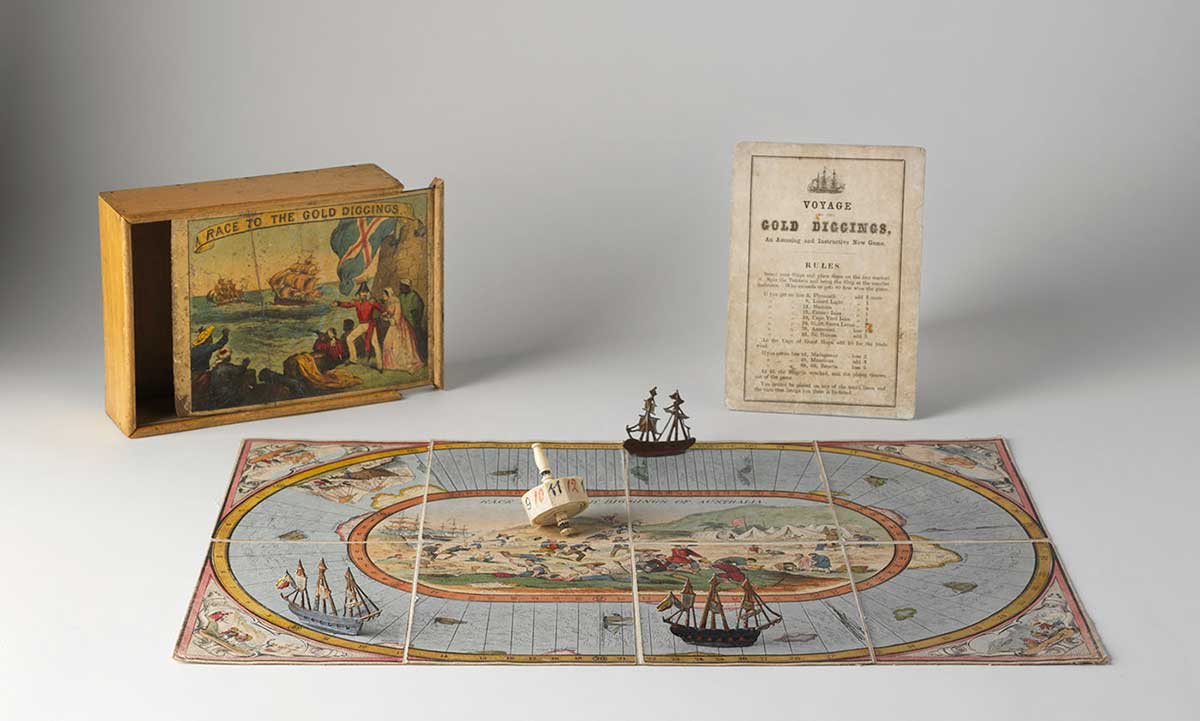

‘Race to the gold diggings of Australia’ board game, about 1855. National Museum of Australia

Migration boom

The discovery of gold started a series of rushes that transformed the other Australian colonies. Significant deposits were discovered in Tasmania from 1852, in Queensland from 1857 and in the Northern Territory from 1871.

In the 1890s a new series of rushes were triggered by the discovery of huge gold fields at Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie in Western Australia.

Between 1851 and 1871 the Australian population quadrupled from 430,000 people to 1.7 million as migrants from across the world arrived in search of gold.

The largest non-European group of miners were Chinese, most of whom were bonded labourers who suffered discrimination from the government and fellow diggers. It’s estimated that by 1855 there were 20,000 Chinese on the Victorian diggings.

Among the larger group of migrants were many men and women bringing new political ideas to the young colonies.

Initially, the colonial establishment resisted such progressive thinking as a threat to their authority and the resulting tensions culminated in the Eureka Stockade . But a groundswell of public opinion brought about a series of world-leading social experiments, such as the secret ballot , the eight-hour day and the formation of the Labor Party .

Australia’s huge reserves of gold made the country a destination for people from around the globe and by the end of the 19th century the rushes had helped create a wealthy, liberal society with a standard of living that was the envy of the world.

Curator Stephen Munro on the significance of the Bealiba gold nugget found near Bendigo.

- australian history

- economics and business

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

William Tipple Smith recognised by the New South Wales Government

Robyn Annear, Nothing but Gold: The Diggers of 1852 , Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1999.

Weston Bate, Victorian Gold Rushes , McPhee Gribble/Penguin, Fitzroy, Victoria, 1988.

David Goodman, Gold Seeking: Victoria and California in the 1850s , Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, USA, 1994.

Geoffrey Serle, Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria, 1851–1861 , Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1977.

Lynette Silver, A fool's gold?: William Tipple Smith's challenge to the Hargraves myth , Jacaranda, Milton, Queensland, 1986.

The National Museum of Australia acknowledges First Australians and recognises their continuous connection to Country, community and culture.

This website contains names, images and voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- Fundamentals NEW

- Biographies

- Compare Countries

- World Atlas

Australian gold rushes

Related resources for this article.

- Primary Sources & E-Books

Introduction

The discovery of gold in New South Wales in 1851 began the first of a series of gold rushes in colonial Australia . The gold rushes transformed the colonies and shaped Australia’s population and society. The lure of gold attracted miners, known as diggers, from all over the world. Tens of thousands of people left their homes and jobs to work long hours in overcrowded and dangerous working conditions. On the Australian goldfields, blacksmiths, butchers, farmers, and ex-convicts worked alongside merchants, doctors, lawyers, and priests. Some struck it rich. Most did not. But all contributed to a defining era of Australian history.

Gold Discoveries

Gold had been found at several sites in Australia prior to 1851, mainly in New South Wales . Colonial governors had kept the discoveries quiet. New South Wales had been founded as a penal settlement , and the population still consisted mainly of convicts and ex-convicts. The government feared that news of a gold discovery would lead to an increase in crime or even a convict uprising. Officials were also concerned about the potential economic effects of gold discoveries. They worried that a gold rush would reduce the workforce and hurt the pastoral industry, which was already struggling after a series of poor seasons. Agricultural products were the colony’s major exports, and as a result the economy was already suffering.

New South Wales

In the 1840s a prominent British geologist named Roderick Murchison predicted that New South Wales had economically significant deposits of gold. His theory soon proved correct. The earliest known payable gold found in Australia was discovered in New South Wales in 1847 by William Tipple Smith, a mineralogist who had read about Murchison’s predictions. Smith found gold in the western slopes of the Blue Mountains near the town of Bathurst. He sent a gold sample to Murchison, who notified the colonial government of the find in 1848. However, government officials declined to take action. That year Smith found more gold in the Bathurst region. In early 1849 he offered to tell the government where he had found the gold if officials would give him a reward to help pay the costs of his expedition. The officials were still not enthusiastic about gold finds, though, and they would not pay him. Smith was largely forgotten to history until the late 20th century, when a historian found letters documenting his gold discoveries.

Meanwhile, the New South Wales government changed its attitude toward gold prospecting after thousands of Australians left the colony for the California gold rush of 1849. The exodus caused labor shortages and an economic downturn. Hoping to revive the economy, the government offered a reward for the discovery of commercial quantities of gold in the colony.

With the government having ignored Smith’s discovery, Edward Hammond Hargraves was for many years widely credited as the first person to find payable gold in Australia. He had come to New South Wales from England in 1832. In 1849 he traveled to the United States to try his luck in the California gold rush. Hargraves found no gold, but he did come away with some valuable information. He noticed similarities in the geography of California’s goldfields and the landscape near Bathurst.

Upon returning to Australia, Hargraves was determined to find gold in the Bathurst region. He assembled a team of miners consisting of John Lister and three brothers, William, James, and Henry Tom. Hargraves taught the men panning, the method of collecting gold that he had learned in California. He also showed them how to build a rocker, or cradle, which was a device that sped up the process of separating gold from other minerals. On February 12, 1851, Hargraves discovered flecks of gold in Lewis Ponds Creek. His assistants, Lister and the Tom brothers, made larger finds in the form of gold nuggets. Hargraves bought the nuggets and, in a successful effort to keep the whole government reward, claimed to have found them himself. He named the area Ophir, after the biblical city of gold. In 1890 New South Wales would finally acknowledge that Lister and the Tom brothers were the real discoverers of the gold.

Meanwhile, in 1851 an account of the discovery was published in the Sydney Morning Herald , and the news quickly spread worldwide. The first Australian gold rush was underway. Within a week more than 400 people had arrived to dig in the area, but that was just the beginning. In the year following the Bathurst discovery, 370,000 immigrants arrived in Australia to seek their fortunes on the goldfields.

When the New South Wales gold rush began, the newly formed colony of Victoria experienced an economic slump. Thousands of workers deserted farms and industries to head north to the Bathurst goldfields. In response, the Victorian government formed a Gold Discovery Committee. It offered a reward to anyone who found gold within 200 miles (320 kilometers) of Melbourne .

The first official discovery was credited to James Esmond, who found gold near the town of Clunes in June 1851. Aboriginal Australians and other white settlers had previously found gold in the region. However, it was Esmond’s find that sparked the Victorian gold rush. Two months later, in August 1851, James Regan and John Dunlop discovered gold in Ballarat, at Poverty Point. Ballarat went on to become the most productive alluvial goldfield in the world at that time. (Alluvial gold refers to gold found in riverbeds, streambeds, and floodplains.) Other discoveries followed at Castlemaine, Daylesford, Creswick, Maryborough, Bendigo, and McIvor. Victoria’s deposits were so rich that the colony accounted for more than one-third of the world’s gold production during the 1850s.

Two discoveries in particular illustrate the extraordinary wealth of Victoria’s goldfields. On June 9, 1858, a group of miners working at Bakery Hill in Ballarat unearthed what at the time was the largest single piece of gold ever found. It weighed approximately 152 pounds (69 kilograms) and was named the “Welcome” nugget. Then, just over a decade later, this record was broken. On February 5, 1869, miners found the “Welcome Stranger” nugget near the town of Dunolly, north of Ballarat. It remains the largest alluvial gold nugget ever found, weighing about 159 pounds (72 kilograms).

Queensland was the next colony to join the gold frenzy. In the mid-1850s, when the land was still part of New South Wales, the colonial government encouraged the search for gold on the northern frontier. It hoped that a discovery would attract European settlers from the south. Captain Maurice O’Connell, the leader of a government settlement at Gladstone, reported “very promising prospects of gold” in 1857. But it was a discovery made a year later that sparked the first Queensland gold rush. A prospector named Chapple found gold at Canoona, near Rockhampton, in July or August 1858. By the end of the year, 15,000 hopeful miners had arrived. The Canoona deposits were small, however, and most of the prospectors were disappointed.

The first major find in Queensland came almost a decade later. In 1867 James Nash discovered gold in the small agricultural town of Gympie, about 90 miles (145 kilometers) north of Brisbane . This was the start of the Gympie gold rush. Within months of Nash’s discovery, 25,000 people came to the area to try their luck. The influx of miners gave a much-needed boost to the struggling economy of the young colony.

Later discoveries sparked other gold rushes in Queensland. In late 1871 an Aboriginal boy, Jupiter Mosman, found gold in a stream in the northeast. The town of Charters Towers was founded at the site, and miners flooded in. The population reached a peak of 30,000 during the gold rush of the 1870s and ’80s. Farther north, a find along the Palmer River pulled miners to the frontier in the mid-1870s. Then, in 1882, Edwin and Thomas Morgan made one of Australia’s most important gold strikes at a site known as Ironstone Mountain, near Rockhampton. The brothers renamed the mountain Mount Morgan after themselves. Mount Morgan, the so-called “mountain of gold,” would become one of Queensland’s richest and longest surviving gold mines. Work would continue at the site until 1981.

Western Australia

The development of Western Australia lagged behind that of the eastern colonies for most of the 19th century, in part because no minerals were found. Its fortunes began to change when gold was discovered in the 1880s. A short-lived rush to the Kimberley district in 1886 was followed by more promising finds in the Pilbara and Yilgarn districts in 1887–88. The next important discovery was made along the Murchison River in 1891.

The Murchison gold rush was soon followed by Western Australia’s two most celebrated finds. In 1892 Arthur Bayley and William Ford struck gold in the south at a site called Fly Flat, which was soon renamed Coolgardie. Then, in 1893, a prospector named Paddy Hannan, working with Tom Flanagan and Daniel Shea, discovered gold at a site 25 miles (40 kilometers) northeast of Coolgardie. The main deposit of deep rich ores came to be known as the Golden Mile reef, and the area developed as Hannan’s Find. The town that grew there was named Kalgoorlie.

The goldfields of Western Australia posed great challenges for diggers. The harsh desert landscape heightened the risk of disease, dehydration, and heatstroke, and many miners died. Nevertheless, the western gold discoveries brought a flood of migrants from the eastern colonies. With New South Wales and Victoria in the midst of an economic depression, many thousands eagerly crossed the continent in search of riches. During the 1890s the population of Western Australia quadrupled, reaching nearly 180,000 in 1900.

Other Discoveries

Gold was also discovered at other sites in Australia. South Australia experienced its first gold rush after a discovery at Echunga in 1852. In the Northern Territory , workers digging during construction of the Overland Telegraph line in 1871 found traces of gold in the stony hills around Pine Creek, south of Darwin. Gold prospectors began arriving through Port Darwin in 1872. In Tasmania , gold finds at a number of sites, including Lefroy in 1869, drew hopeful diggers. However, the quantities of gold unearthed at these sites were much smaller than those in the eastern states and Western Australia, so the gold rushes were smaller as well.

Immigration Boom

The gold rushes had an immense impact on Australia’s population. News of the 1851 discoveries attracted people from countries around the world. Over just two decades, immigration quadrupled Australia’s population, from 438,000 in 1851 to 1.7 million in 1871. As the population expanded, it also began to diversify. Other than the Aboriginal peoples, the colonial population before the gold rushes consisted almost entirely of people from the British Isles. Although the majority of the new immigrants also came from the United Kingdom, they were joined by prospectors from the United States, Germany, France, Italy, Poland, Hungary, and other countries. The gold rush era was also the first time that Australia experienced a significant influx of Chinese immigrants. By 1861 more than 38,000 Chinese lived in Australia, making up more than 3 percent of the population. More than 12,000 Chinese arrived in the year 1856 alone.

Chinese prospectors experienced much hardship and mistreatment on the Australian goldfields. Most were under contract to Chinese and foreign businessmen. In exchange for their passage to Australia, they had to work until they paid off their debt and could then return to China. European and American diggers were suspicious of the Chinese, with their different language, clothes, food, religious practices, and customs. Moreover, they resented the success of the Chinese and their unique mining methods. The Chinese were particularly hardworking and efficient. Unlike European and American miners, who worked alone or in small groups, the Chinese worked together in teams of 30 to 100 men. They preferred to rework claims that had been abandoned by other miners rather than exploring new ground. In this way, they often found gold that others had overlooked.

Strong anti-Chinese sentiment arose on the goldfields, and many racially fueled riots erupted. Some of the most violent riots took place at Lambing Flat (now known as Young) in New South Wales in 1860–61. In the last of these disturbances, on June 30, 1861, some 3,000 European and American miners attacked a Chinese camp. They beat the Chinese, burned their tents, and cut off their queues (traditional long hair braids). In response to the riots, the New South Wales government passed the Chinese Immigration Act to greatly reduce the number of Chinese migrating to the colony. Restrictions on Chinese immigration were also introduced in Victoria (1855), South Australia (1857), Queensland (1877), and Western Australia (1886). ( See also immigration to Australia .)

Life on the Goldfields

Living conditions on the goldfields were harsh for everyone—diggers, women, and children. To reach the goldfields, prospectors usually had to travel long distances on foot, carrying all their possessions, because no roads had been built and horse transportation was too expensive. Once they arrived, they had to set up tents for shelter. Early tents were very simple, usually consisting of a piece of canvas draped over a tree branch. They were not secure, and on many occasions miners had their belongings stolen. The tents also provided little protection from snakes and insects. These conditions are one reason why men usually traveled to the goldfields alone in the early years of a gold rush. Their families would join them later, once diggers had made their dwellings more livable.

If a miner was able to establish a profitable claim, he would typically build a bark hut. Some diggers who decided to stay for a long time or who had brought their families with them built more permanent homes. They constructed huts using wooden slabs, mud bricks, or wattle and daub—a frame of poles and woven branches plastered with mud or clay. These homes were small and cramped, with only one or two rooms for the whole family. The children usually slept together in one bed and the parents in another. A fireplace was used for cooking and for providing heat in winter. Furniture was sparse and handmade using wood and any other materials on hand, such as recycled boxes. Only wealthy miners could afford more elaborate furnishings. On the more populated and profitable goldfields, houses, hotels, and shops were established.

Many people became disillusioned with life on the goldfields. Most foods were in short supply and therefore very expensive. The typical digger’s diet was restricted and repetitive, consisting mostly of meat and damper, a type of bread made with flour, baking powder, water, and salt. Meat was readily available from local pastoralists with herds of sheep and cattle. The staple meat, especially in the early gold rush days, was mutton (sheep). Because there was no refrigeration, meat had to be eaten within a short time. Sometimes meat was preserved by rubbing salt over it. Bacon, ham, butter, and cheese were luxury items that only successful miners could afford.

Clean drinking water was hard to find. Rivers and creeks were polluted by the mining process and, in the absence of a sanitation system, by human waste. Water had to be boiled to make it safe to drink. Diggers drank black tea with most meals. They prepared it by boiling water over a campfire in a tin pot called a billy. They drank it from a tin mug called a pannikin.

In the early gold rush years, miners were not permitted to plant vegetable gardens. This policy was meant to discourage miners from establishing permanent homes. In 1853, however, the Victorian government allowed vegetable gardens on the goldfields. Chinese immigrants played a vital role in supplying fresh vegetables, and the diggers came to rely on this produce. Most of the Chinese prospectors had come from southern China, where they had worked as farmers. As the gold supply started to decline, many Chinese turned to market gardening, putting their knowledge and skills to work. They settled near towns and cities and became successful business owners. Many profited more from providing fresh food for the growing settlements than from searching for dwindling gold deposits.

The poor living conditions on the goldfields made it difficult to stay healthy. Infectious diseases spread easily through the settlements. Many people became ill with typhoid fever , cholera , or dysentery, all of which are caused by ingesting contaminated water or food. Diets lacking in fresh fruits and vegetables led to vitamin C deficiencies and the disease called scurvy. Other common diseases included influenza , pneumonia , scarlet fever , and diphtheria . Medical treatment was hard to find on the goldfields, and it was too expensive for most miners. Those who could not afford a doctor often turned to apothecaries. Apothecaries made medicines using plants and other local ingredients. They also provided medical advice, performed surgery, and delivered babies.

Mining was a dangerous pursuit, and accidents were common. Diggers were trapped by collapsing mine shafts and injured by machinery. They were also exposed to poisonous gases in mine tunnels. Many mining accidents were deadly. In the town of Ballarat alone, one miner was killed in an accident on average every week in 1859.

Men were always a majority on the goldfields, but the number of women grew as the years went on. The Ballarat goldfields, for example, had 4,023 women living alongside 12,660 men in 1854. By 1861 the proportion of women had increased significantly, with 9,135 women compared to 12,726 men. Most of the women on the goldfields were wives who joined their husbands a few years after a rush began, but a small number were single.

Women played an important role on the goldfields in many ways. A few dug for gold, either with their husbands or on their own. Some made clothes, hats, or shoes. Others set up shops or ran hotels. Most women, however, worked in the home, performing domestic duties and raising children. Some chores, such as cooking meals and washing dishes, were done every day. Others were scheduled for certain days of the week. The most difficult day was washing day. After miners spent all day digging in mud or clay, their clothes were very dirty. All clothes and linen had to be washed by hand by soaking each item in soapy water and scrubbing it against a washboard to get the dirt out. Other days were set aside for cleaning, sewing and mending, cooking and baking, and ironing, which was done with an iron heated over a fire. All bread, jams, soap, and candles had to be made by hand. If a family owned a cow, the women milked it and made butter.

Life could be both difficult and exciting for children during the gold rushes. Children were expected to help with many household chores. They fetched water from the well or river, gathered firewood, fed the horses, washed clothes, and looked after younger siblings. Older children often helped on the goldfields. They shoveled rock and gravel, panned for gold, and worked the rocker.

Children were not required to go to school at the time of the gold rushes. Parents who chose to send their children to school had to pay, and some families could not afford the fees. In addition, parents often chose to keep their children out of school so they would have more time to help with chores and prospecting. Some parents sent their sons to school but not their daughters. They thought it was more important for boys to get an education because girls could learn what they needed to know—how to knit, sew, cook, clean, and iron—at home with their mothers. The first classes were held in tents that the teacher could take down and move when miners moved from one goldfield to another. Later, religious groups held classes in churches. Eventually the government built schools in the larger settlements.

When children were not helping at home or going to school, they were expected to amuse themselves with whatever was around. They played marbles , jacks , and quoits , a game in which rings made of rope are thrown over a peg. They played jacks using knucklebones, the small bones found in the joints of sheep and cows. Other common toys included wooden soldiers, rag dolls, jump ropes, wooden blocks, and spinning tops.

Children, along with the rest of the family, took a bath once a week. The water was heated in a kettle over the fire or on a stove and poured into a tin tub. One family member at a time sat in the tub to wash themselves.

Children on the goldfields were at the greatest risk from infectious diseases because of their less developed immune systems. Although a vaccine was available to protect against smallpox, the lack of other vaccines left children vulnerable to deadly illnesses. With poor nutrition, sanitation, and medical supplies, many babies and young children died.

Law and Order

Only a small number of the many thousands of hopeful diggers were lucky enough to find gold. As dreams of riches faded, disappointment and frustration grew. Some diggers resorted to crime. They might steal another’s belongings or his gold. Claim jumping—taking someone else’s claim—was common, and disputes often turned violent. Many diggers armed themselves to protect themselves and their claims.

The gold rushes attracted some men who planned to make a fortune without digging for gold at all. Bandits known as bushrangers attacked and robbed miners traveling between goldfields. Because there were no banks on the goldfields, diggers had to carry their gold with them as they moved from place to place. As they moved through the isolated bush, they were easy targets for thieves.

Without police, judges, or other authorities to keep order, the first miners had to work out a system of law and order for themselves. Groups of miners established courts to put accused criminals on trial and to hand out punishments to those found guilty. Soon this makeshift system was supplemented by efforts of the colonial governments. Officials in New South Wales and Victoria appointed a gold commissioner to oversee each goldfield. The commissioners were assisted by troopers (mounted police) and foot police, who were known by the miners as “joes” or “traps.”

The colonial governments had a hard time finding police because many officers, like thousands of others, had left their jobs to join the gold seekers. In the early gold rush years they relied on the Native Police, a force made up Aboriginal men. The Native Police were effective because their close knowledge of the land helped them to track bushrangers and other criminals. To supplement this force, however, governments had little choice but to accept anyone who was willing to join the police. This meant that the force included ex-convicts, ex-wardens, and many young, inexperienced recruits.

The gold commissioners regulated the goldfields and resolved disputes between miners. They also offered a service designed to move gold securely from the fields to cities for safekeeping. For a fee, diggers could turn over their gold and have it transported on heavily guarded coaches. The “gold escorts” carried thousands of pounds of gold from remote goldfields to Sydney, Melbourne, and other cities each week.

The gold escorts provided some security, but they could not prevent bushranger attacks. Bushrangers typically had excellent knowledge of the land and were skilled at riding horses and using guns. Their attacks became more frequent as the quantities of gold increased. The most famous gold escort robbery took place in New South Wales on June 15, 1862. Frank Gardiner and his gang, which included Ben Hall and John Gilbert, held up a coach at Eugowra as it was traveling from Forbes to Orange. The bushrangers escaped with £14,000 in gold and banknotes, which was an enormous sum. Gardiner was arrested two years later and spent 10 years in prison for the Eugowra robbery. Other famous bushrangers of the gold rush era included Andrew George Scott (known as “Captain Moonlite”), Frederick Ward (“Captain Thunderbolt”), the Clarke brothers, and Ned Kelly .

To cover the costs of maintaining law and order on the goldfields, the governments of New South Wales and Victoria introduced a license system. Every miner had to pay a high fee—30 shillings a month—for a license, even if they did not find gold. The license had to be carried at all times, and a miner who failed to show one could be fined or arrested. The police charged with enforcing the license system were notorious for corruption and for their brutal methods. Miners also resented that they could not vote and that they had no representatives in the government. For all these reasons, miners reacted to the license requirement with considerable anger.

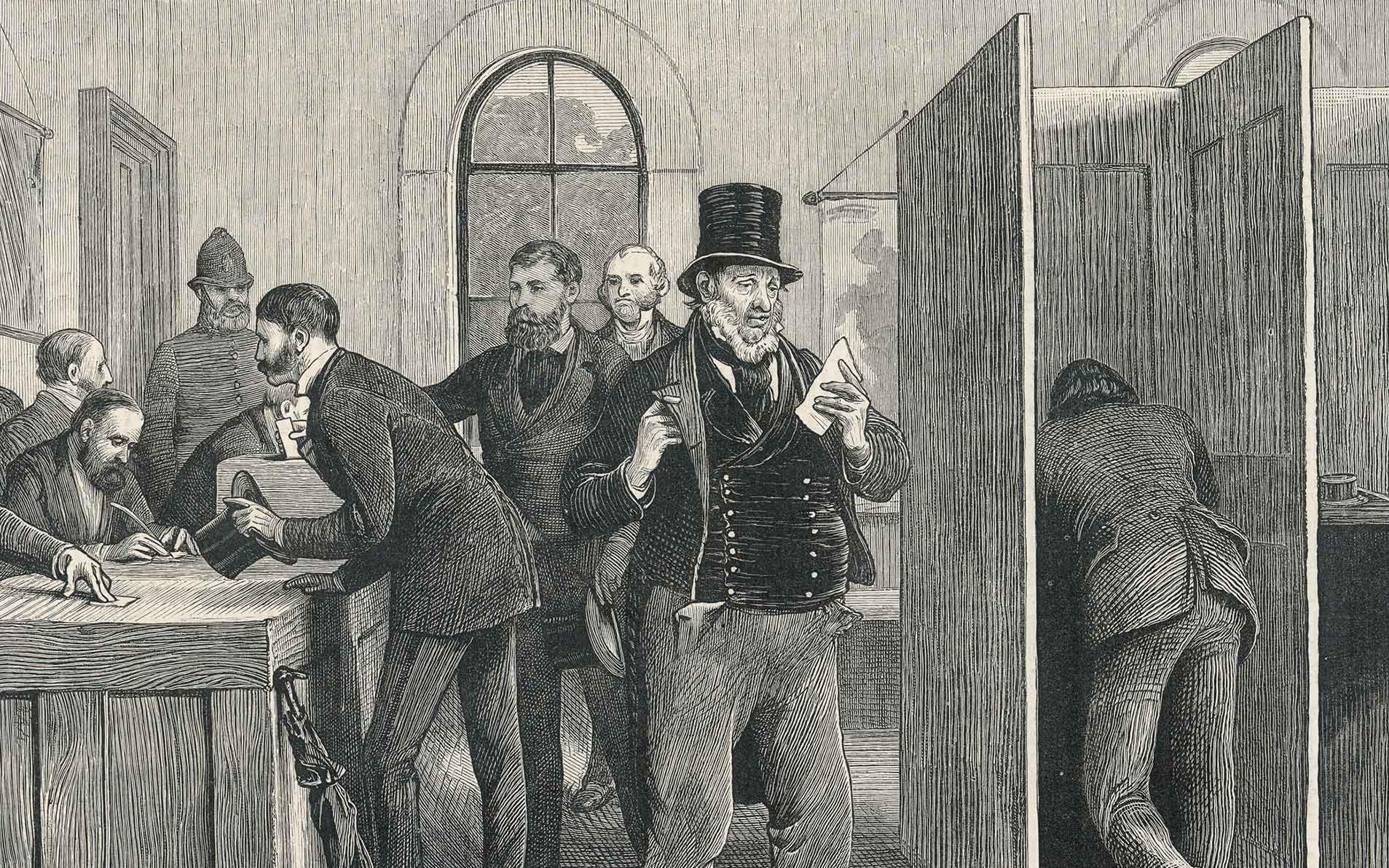

Opposition to the license system reached its height at Ballarat in 1854, in what became known as the Eureka Stockade or the Eureka Rebellion. Diggers formed the Ballarat Reform League and petitioned the government for change. When their demands were refused, they formed military companies, marched to the Eureka goldfield, and built a stockade. On December 3, 1854, police and military troops attacked the stockade and defeated the diggers, killing more than 20 of them. In the aftermath of the rebellion, however, the government met most of the diggers’ demands. The Victorian government replaced the license requirement with a much fairer system in which miners paid a tax on gold they found instead of paying whether they found gold or not. Diggers were also given the right to vote and representation in the Victorian legislature. The Eureka Stockade proved to be a defining moment in the development of Australian democracy.

The gold rushes of the 19th century had profound social, political, and economic effects on Australia. The immigration boom led to a dramatic increase in population and began to diversify the colonies’ predominantly British society. Some immigrants who came up empty in the gold rush went on to become prominent in business, law, or politics. The gold rushes spurred the exploration and settlement of remote lands, pushing the frontier in Queensland and Western Australia in particular.

The economic boost brought on by the gold discoveries was crucial in the modernization of colonial Australia. During the 1850s the colonies accounted for more than 40 percent of the world’s gold production. This rapid rise catapulted Australia onto the international stage and helped create a wealthy society with probably the highest standard of living in the world at the time. Gold profits were used to establish towns and to transform existing cities with new banks, stores, hotels, and other businesses. The flood of miners and money into Victoria made Melbourne a boomtown and the continent’s largest city. Rural industries expanded as well, as pastoralists increased production of meat and hides to meet the demand of growing cities. The gold rush era also saw large investments in transportation, with the construction of roads, railways, and bridges to move people to and from goldfields and cities.

The impact on the political development of Australia was long lasting. The Eureka Stockade was a catalyst for change, and people started to demand democratic reforms. This movement was also encouraged by new immigrants who brought with them ideas of democracy and equality from Europe and the United States. The calls for reform began to yield results in 1856, when South Australia gave all adult males the right to vote and South Australia and Victoria introduced the secret ballot.

Not all Australians shared equally in the progress of the gold rush era, however. The anti-Chinese sentiment that took root on the goldfields in the 1850s continued to build as new Chinese businesses and communities thrived. European colonists resented what they perceived as economic competition. Their anger would eventually be embodied in the White Australia Policy of 1901, which severely limited Chinese immigration to Australia for more than 50 years.

Some Aboriginal Australians found economic opportunities during the gold rushes. They sold food and clothes to the diggers, and some found their own gold and used it for trade. Aboriginal Australians also played a valuable role as guides and trackers for the Europeans who knew nothing of the land. In the end, however, the gold rushes mostly just added to the challenges that Aboriginal Australians had been facing since European colonization began. The miners invaded their lands, caused great environmental damage, and generally disrupted traditional Aboriginal ways of life.

Before the 1850s, Australia was a remote, little-known colony populated mainly by British convicts. But within months of the discovery of gold in 1851, Australia had an international reputation. The changes brought about by the first gold rushes transformed Australia and set its course of development for decades to come. Just 50 years after the fateful find at Bathurst, the British colonies would unite to become the independent Commonwealth of Australia.

It’s here: the NEW Britannica Kids website!

We’ve been busy, working hard to bring you new features and an updated design. We hope you and your family enjoy the NEW Britannica Kids. Take a minute to check out all the enhancements!

- The same safe and trusted content for explorers of all ages.

- Accessible across all of today's devices: phones, tablets, and desktops.

- Improved homework resources designed to support a variety of curriculum subjects and standards.

- A new, third level of content, designed specially to meet the advanced needs of the sophisticated scholar.

- And so much more!

Want to see it in action?

Start a free trial

To share with more than one person, separate addresses with a comma

Choose a language from the menu above to view a computer-translated version of this page. Please note: Text within images is not translated, some features may not work properly after translation, and the translation may not accurately convey the intended meaning. Britannica does not review the converted text.

After translating an article, all tools except font up/font down will be disabled. To re-enable the tools or to convert back to English, click "view original" on the Google Translate toolbar.

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

History Hit Story of England: Making of a Nation

10 Facts About the Australian Gold Rush

Peta Stamper

26 jan 2022.

On 12 February 1851, a prospector discovered small fragments of gold in a waterhole near Bathurst in New South Wales, Australia. This discovery opened the floodgates to migration and enterprise which soon spread across the continent, from Victoria and News South Wales to Tasmania, Queensland and beyond.

‘Gold fever’ seemed to have infected the world and brought prospectors from Europe, America and Asia to Australia. Alongside gold, what many of them found was a new sense of identity that challenged British colonial society and changed the course of Australian history.

Here are 10 facts about the Australian gold rush.

1. Edward Hargraves was hailed as the ‘Gold Discoverer of Australia’

Hargraves had left Britain aged 14 to make a life for himself in Australia . A jack of all trades, he worked as a farmer, storekeeper, pearl- and tortoise-sheller and sailor.

In July 1849, Hargraves ventured to America to take part in the Californian gold rush where he gained valuable knowledge in how to prospect. Although he did not make his fortune in California, Hargraves returned to Bathurst in January 1851 determined to put his new skills to good use.

2. The first gold discovery was made on 12 February 1851

Hargraves was working along Lewis Pond Creek near Bathurst in February 1851 when his instincts told him gold was close by. He filled a pan with gravelly soil and drained it into the water when he saw a glimmer. Within the dirt lay small flecks of gold.

Hargraves sped to Sydney in March 1851 to present soil samples to the government who confirmed he had indeed struck gold. He was rewarded with £10,000 which he refused to split with his companions John Lister and the Tom Brothers.

Painting of Edward Hargraves returning the salute of the gold miners, 1851. By Thomas Tyrwhitt Balcombe

Image Credit: State Library of New South Wales / Public Domain

3. The gold discovery was publicly announced on 14 May 1851

The confirmation of Hargraves’ discovery, announced in the Sydney Morning Herald , began New South Wales’ gold rush, the first in Australia. Yet gold was already flowing from Bathurst to Sydney before the Herald ‘s announcement.

By 15 May, 300 diggers were already on site and ready to mine. The rush had begun.

4. Gold was found in Australia before 1851

Reverend William Branwhite Clarke, also a geologist, found gold in the soil of the Blue Mountains in 1841. However, his discovery was quickly hushed by colonial Governor Gipps, who reportedly told him, “put it away Mr Clarke or we shall all have our throats cut”.

5. The Victorian gold rush dwarfed the rush in New South Wales

The colony of Victoria, founded in July 1851, began haemorrhaging inhabitants as people flocked to neighbouring New South Wales in search of gold. Therefore, Victoria’s government offered £200 to anyone who found gold 200 miles within Melbourne.

Before the end of the year, impressive gold deposits had been found in Castlemaine, Buninyong, Ballarat and Bendigo, overtaking the goldfields of New South Wales. By the end of the decade, Victoria was responsible for over a third of the world’s gold findings.

6. Yet the biggest single mass of gold was found in New South Wales

Weighing in at 92.5kg of gold stuck within quartz and rock, the enormous ‘Holtermann Nugget’ was discovered in the Star of Hope mine by Bernhardt Otto Holtermann on 19 October 1872.

The nugget made Holtermann a very rich man once it had been melted down. Today, the value of the gold would be worth 5.2 million Australian dollars.

A photograph of Holtermann and his giant gold nugget. The two were in fact photographed separately before the images were superimposed onto one another.

Image Credit: American & Australasian Photographic Company / Public domain

7. The gold rush brought an influx of migrants to Australia

Some 500,000 ‘diggers’ flocked to Australia from far and wide in search of treasure. Many prospectors came from within Australia, while others travelled from Britain, the United States, China, Poland and Germany.

Between 1851 and 1871, the Australian population exploded from 430,000 people to 1.7 million, all headed ‘off to the diggings’.

8. You had to pay to be a miner

The influx of people meant limited finances for governmental services and the colonial budget was struggling. To discourage the tidal wave of newcomers, the governors of New South Wales and Victoria imposed a 30 shilling a month licence fee on miners – a pretty substantial sum.

By 1852, the surface gold had become ever harder to find and the fee became a point of tension between the miners and government.

9. New ideas about society led to conflict with the British colonial state

Miners from the town of Ballarat, Victoria, began to disagree with the way the colonial government administered the goldfields. In November 1854, they decided to protest and built a stockade at the Eureka diggings.

On Sunday 3 December, government troops attacked the lightly guarded stockade. During the assault, 22 prospectors and 6 soldiers were killed.

Although the colonial government had resisted the change in political attitudes, public opinion had shifted. Australia would go on to pioneer the secret ballot and the 8-hour working day, both key to building Australia’s representational structures.

10. The Australian Gold Rush had a profound impact on the country’s national identity