An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the health sciences: Best practice methods for research syntheses

Blair t johnson, emily a hennessy.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author. Department of Psychological Sciences, 406 Babbidge Road, Unit 1020, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, 06269-1020, USA. [email protected] (B.T. Johnson).

Issue date 2019 Jul.

The journal Social Science & Medicine recently adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009 ) as guidelines for authors to use when disseminating their systematic reviews (SRs).

After providing a brief history of evidence synthesis, this article describes why reporting standards are important, summarizes the sequential steps involved in conducting SRs and meta-analyses, and outlines additional methodological issues that researchers should address when conducting and reporting results from their SRs.

Results and conclusions:

Successful SRs result when teams of reviewers with appropriate expertise use the highest scientific rigor in all steps of the SR process. Thus, SRs that lack foresight are unlikely to prove successful. We advocate that SR teams consider potential moderators (M) when defining their research problem, along with Time, Outcomes, Population, Intervention, Context, and Study design (i.e., TOPICS + M). We also show that, because the PRISMA reporting standards only partially overlap dimensions of methodological quality, it is possible for SRs to satisfy PRISMA standards yet still have poor methodological quality. As well, we discuss limitations of such standards and instruments in the face of the assumptions of the SR process, including meta-analysis spanning the other SR steps, which are highly synergistic: Study search and selection, coding of study characteristics and effects, analysis, interpretation, reporting, and finally, re-analysis and criticism. When a SR targets an important question with the best possible SR methods, its results can become a definitive statement that guides future research and policy decisions for years to come.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Systematic reviews, Evidence synthesis, Research synthesis, Methodological quality, Risk of bias

1. Introduction

Because they organize information from multiple studies on a subject, systematic reviews (SRs) have become an increasing important form of scientific communication: As a proportion of reports in PubMed, SRs increased over 14000% since 1987, over 500% since 2000, and over 200% since 2010. Social Science & Medicine recently adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009 ) reporting standards and guidelines for authors to use when developing their review manuscripts for publication. This article describes in detail why such reporting standards are important and outlines methodological issues that researchers should address when conducting and reporting results from their SRs.

To set the stage, we first briefly review the history of the practice of research synthesis. Then, we offer a series of recommendations for future SRs based on our experience conducting, peer reviewing, and editing SRs. We also (a) recommend improvements for some conventions, such as a priori consideration of potential moderators that may be associated with different results; and (b) compare the PRISMA reporting standards with a popular measure of the quality of meta-analysis, the AMSTAR 2 ( Shea et al., 2017 ), concluding that simply reporting methods according to the PRISMA checklist is no guarantee of a high quality SR. Although we (c) make best practice suggestions for methods involved in systematic reviewing across all disciplines, in this article, our focus is on the health sciences. We place special emphasis on the notion that a SR should take a team approach – to be rigorous and useful to the field, reviews must have authors with substantive and methodological expertise and many tasks should be performed in duplicate to reduce errors. In writing this article, our hopes are to empower readers to determine whether a particular SR “embodies ‘megaenlightenment’ or ‘mega-mistake’” ( Nakagawa et al., 2017 ), to enable research syntheses of the highest standards to appear in publications, and to spur better scientific knowledge, along with meaningful improvements in practice. Although the examples we use are drawn from health-related literature, the methods are drawn comprehensively from across science.

2. Meta-analysis is the ‘original big data’

In essence, SRs compile the results of two or more independent studies on the same subject. SRs may or may not have quantitative component to summarize the outcomes of the studies reviewed (viz. meta-analysis). In conventional practice, the term meta-analysis is often used to presume that the evidence has first been systematically retrieved and reviewed. (Similarly, meta-analytic methods may pool any two or more studies, without otherwise being systematic about gathering comparable other studies.) As another form, meta-syntheses integrate qualitative information gathered from multiple studies of the same phenomenon. In turn, meta-reviews (viz. scoping reviews, overviews) are reviews of reviews. Whether a SR, meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, or meta-review, all SRs are a form of evidence or research syntheses.

Although many narratives on the history of systematic reviewing call attention to Karl Pearson’s ( Simpson and Pearson, 1904 ) integration of correlations pertaining to the effectiveness of a typhoid vaccine as the original SR with meta-analysis, this practice has a much longer history. In fact, pooling data is a central concept of Bayes’ ( Bayes et al., 1763 ) theorem, such that a prior based on previous observations improves the prediction of a future outcome. Unfortunately, this strategy was not routinely applied until the early 1800s and was not applied rigorously or widely until the computer age, when modern software made it more feasible.

In terms of actual pooling of data from independent studies, historian of statistics Stephen M. Stigler (1986) documented that the practice appeared as early as 1805; astronomers, for example, gained additional precision by pooling their separate observations of the same cosmic events. This practice of quantitatively pooling study results was not termed meta-analysis until Gene V. Glass (1976) coined it. Given (a) that the practice of data pooling has existed for far longer than even primitive electronic computers have existed, and (b), that the essence of SRs has been to pool all available data on the subject (i.e., to be the biggest database yet available), it is clear that meta-analysis is the original big data.

Although one might suspect that the health sciences first recognized the importance of the SR process, ironically, as Chalmers et al. (2002) documented, the first may well have been the 19th century physicist, John William Strutt, a Nobel Prize winner who wrote:

“If, as is sometimes supposed, science consisted in nothing but the laborious accumulation of facts, it would soon come to a standstill, crushed, as it were, under its own weight … [what ] deserves, but I am afraid does not always receive, the most credit is that in which discovery and explanation go hand in hand, in which not only are new facts presented, but their relation to old ones is pointed out” ( Strutt, 1884 , p. 20)

Whereas some conceptual and computational strategies were available in the 19th century for reviews, methodological training of the time was starkly unaware of the problems of poor SR methods. Thus, Strutt had a good idea but lacked the methods to generate high quality SRs, and the practice of reviewing scientific literature remained a dubious one that permitted personal biases to interfere with accurate conclusions. Consumers of literature reviews tended to trust those presented by scholars who had conducted many studies in a domain, and, who, not surprisingly, usually confirmed not only the trends in their own studies but also their own pet theories. Thus, these were reviews, but they were rarely if ever systematic, at least not until late in the 20th century, when following Glass’s (1976) lead, scholars increasingly became aware that reviewing of scientific studies is itself a scientific method that must be carefully applied and made transparent enough that independent scholars can judge the validity of the conclusions; indeed, transparency is necessary in order to replicate these results. In short, accurate, comprehensive pooling of results offers the potential for increasingly better understanding of a given phenomenon. It means, for example, that the conditions when treatments can improve health outcomes will become better known, or that the plausible causes of a health condition or outcome will be better known.

As the 20th century advanced, the statistics behind pooling evidence became increasingly sophisticated, and, with computers to aid them, pooling large numbers of studies became a routine activity, helping to ignite what Shadish and Lecy (2015) dubbed the “meta-analytic big bang.” At the same time, the numbers of studies on seemingly every subject grew exponentially, such that science often seemed to be crushed under its own weight, to borrow Strutt’s words. In essence, some scientific phenomena may be too popular subjects among scientists for their own good. And, specific phenomena may comprise such a large mass of data that they are humanly impossible to cumulate into a comprehensive SR without using quantitative strategies ( Johnson and Eagly, 2014 ).

This narrative should not be taken to imply that SRs’ success as a scientific strategy has been linear and without controversy. To be sure, controversies emerged, although it is intriguing that the most forcible resistance emerged from scholars who found their own pet hypotheses challenged by upstart SRs ( Chalmers et al., 2002 ). In recent decades, scholars have jumped on the SR bandwagon under the recognition that, by pooling data from all relevant independent studies, the promise is that human welfare and activities will improve. Unfortunately, some commercial entities have also attempted to use the popularity of SRs as a tool to improve their own economic bottom lines; for example, a recent meta-review documented that meta-analyses with industry involvement (e.g., authors on the staff of big pharmaceutical companies) are massively published: 185 meta-analyses of antidepressant trials appeared in a seven-year stretch ( Ebrahim et al., 2016 ) and they seldom reported caveats about the drugs’ efficacy ( Ebrahim et al., 2016 ; Ioannidis, 2016 ).

Aided in large part by the exponential growth in SR and meta-analytic software ( Polanin et al., 2017 ; Viechtbauer, 2010 ), it is now possible for authors to generate meta-analytic statistics quickly and efficiently. Yet, it is clear that doing so is no guarantee of a rigorous and trustworthy SR. Indeed, conducting and publishing a SR with less than optimal methods may actually worsen human welfare ( Ioannidis, 2010 ). Importantly, rigorous SRs are in the best position to identify subjects for which the evidence is the thinnest. Thus—at their best—SRs help to focus resources on the most needed new research. In short, science crucially needs strong SRs.

3. Assumptions involved in systematic reviews

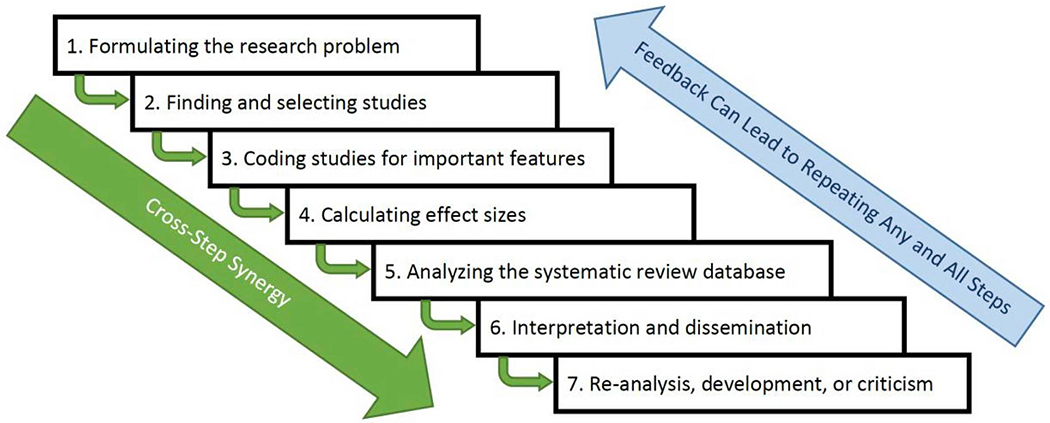

The foregoing history did not detail specifically how it is that poor rigor may undermine SRs. To put these assumptions into perspective, we describe the basics of systematic reviewing, characterized as seven main steps, which Fig. 1 briefly summarizes. (For more nuanced discussions or tutorials see, e.g., Borenstein et al., 2011 , Card, 2015 , Higgins, 2008 , Siddaway et al., 2019 ). This section outlines the assumptions involved in systematic reviews by organizing them by step of the SR process. First, the steps are highly synergistic: As Fig. 1 depicts, rigorous work in the earlier steps facilitates better progress on the later steps as well as better, more transparent reporting. Importantly, if early steps of the process are undertaken with low rigor, then a systematic review’s conclusions ought to be regarded with considerable suspicion. Similarly, SR teams often refine their methods as the process continues, which entails returning to repeat earlier steps of the process until the SR is completed with sufficient quality. Table 1 summarizes the advice that we provide in the remaining sections of this article.

The meta-analysis process depicted in seven steps that build on each other and that sometimes must be repeated as feedback learned during the process emerges.

Methodological steps necessary to conduct systematic reviews (SRs), along with best-practice recommendations (the text expands on these points).

3.1. Formulating the research problem

In Step 1, the SR team formulates the research problem, a step that relies on the SR team members’ understanding of the literature from both a substantive and methods (including statistical assumptions) perspective. Importantly, if the team lacks this strong conception, then the SR will not be worth doing. Note that Step 1 is crucial from a practical standpoint: The broader the research problem, the more resources will be needed to complete the review in a reasonable time-frame. Thus, a poorly framed SR may amount to a waste of valuable resources. Such a SR may become so cumbersome that it may not even be completed at all–or may take so long to complete that the literature is irrelevant by publication. Reviewing prior SRs may help to guide the team by identifying the more interesting questions that a new SR could address. Doing so also ensures that the new SR is worth the massive resources that are often needed for it to be rigorous and comprehensive. Importantly, such an initial scoping search of the existing synthesis literature may demonstrate whether a new SR should even be conducted (e.g., because past SRs lacked rigor or are out of date) or may highlight how a different focus could enhance the existing literature base. The SR team should search online registries (e.g., Prospero, Cochrane Collaboration, Campbell Collaboration), evidence gap maps, and individual journals relevant to their discipline to see if similar SRs are already in progress or have been conducted and whether these address the same questions. If a team judges extant or ongoing SRs as rigorous and as having addressed the most important questions, then there is no reason to continue. In contrast, if there is a strong need for a new SR and the team has the necessary conceptualization, then the remaining steps of the process may also be formalized in advance and with high rigor. As part of this process, authors of the proposed review should describe existing review literature and how this new review would build upon those previous reviews prior to embarking on a new review, a section that could then be incorporated in the final review manuscript.

When the SR focuses on a particular treatment, formulating a research problem routinely utilizes a form of the PICOT, PICOS acronyms ( Haynes, 2006 ), or, as we introduce, the TOPICS + M acronym:

T: Time may concern the period when studies are of interest (e.g., if the SR team is conducting a rapid review, typically only focusing 12 or 18 months’ worth of studies) or may involve questions around duration of effects (e.g., interventions immediate effect versus longer-term outcomes). It also may concern how an effect is changing over time for a particular population (e.g., that perceived racism’s linkage to depression is worsening with time).

O: The outcome is the measure or measures used to evaluate the impact of the intervention (e.g., depressive symptoms). To prevent reporting bias, it is ideal to pre-specify eligible outcomes with as much detail as possible: Depending on the focus and scope of the review, it may also be necessary to detail the type of measure of the outcome that is relevant for the review (e.g., only standardized measures of the outcome, such as objective measures of blood pressure).

P: SRs must address the population to which the chosen topic is most relevant, which may vary from clinical diagnoses (e.g., patients with high levels of depressive symptoms) to ethnic and/or racial groups. We recommend also specifying the geographic locale(s) of interest (e.g., Latinx who have recently immigrated to the U.S.) as it will affect the choice of literature sources, especially the location of grey literature.

I: If the SR concerns treatments, then interventions refers to the particular type of treatment provided to samples from the population (e.g., mindfulness training to reduce stress).

C: The comparison references the standard to which the intervention is compared. Treatment studies routinely include control groups such as standard of care or placebo. Alternatively, a treatment study may compare multiple treatments or may instead focus on one treatment and use baseline levels of a condition to examine how much the condition changes over time.

S: Study design refers to the method used to evaluate the phenomenon in question, such as randomised controlled trials (RCTs), uncontrolled trials, and cohort or cross-sectional studies. SRs often focus on study design types that are considered high quality (e.g., only RCTs), but there is a strong caveat to this focus. Because it is usually not clear what makes for the best possible study for a given problem, and the most ecologically valid studies may in fact suffer flaws, methodologists ( Johnson et al., 2015 ) have recommended broader samples of designs, so that it can be determined whether, in fact, results differ between contrasting study design types. (We return to this issue in Step 3.) If the goal is a meta-review (a review of reviews), then the type of review targeted should be stated (e.g., meta-analyses, meta-syntheses).

M: Moderators (also known as effect modifiers ) are factors that the SR team evaluates for their potential associations with outcomes. We add “M” because it is nearly always the case, even in medical literature ( Higgins et al., 2003 ), that studies exhibit significant levels of heterogeneity; that is, treatment studies’ effects routinely vary more than sampling error expects them to vary. The existence of heterogeneity implies the presence of one or more factors that make study effects vary and that may be present in some of the included studies or differ across included studies. Consequently, it nearly always benefits a SR team to consider what factors may make their effects larger or smaller, more positive or more negative. Of course, to the extent that there is variation in the TOPICS elements, these too can serve as moderators. If moderators are included in a SR, then they are often added as secondary questions to be answered, but we recommend pre-specifying them at the protocol stage and thus we have incorporated the “M” element into the standard PICOS framework. Finally, we recommend that, even if the SR team has no a priori expectations about moderators, they should still specify “M” elements; instead these can act as sensitivity analyses (e.g., to show that an intervention is equally efficacious across men and women or across racial categories). For example, Lennon et al.’s (2012) SR focused on HIV prevention interventions for heterosexual women; this SR team theorized that intervention success hinges on levels of depression the women have at the outset of the trial (we return to this example, below). Notably, this factor had never been considered in prior meta-analyses of HIV prevention trials, making it a hidden moderator ( Van Bavel et al., 2016 ).

TOPICS + M affords a linguistic advantage as well as a methodological one, as literally SRs must define their topic of focus (plus moderators), although original sources on PICO imply theorizing about moderators (e.g., Haynes, 2006 ). Note that, as we elaborate below, some methodological quality scales also give credit to SRs that make a priori attempt to determine causes of heterogeneity (e.g., Shea et al., 2017 ). Numerous other definitions similar to TOPICS + M exist, and we summarize some prominent ones in Table 2 ; some of these are useful for non-intervention study designs. Whether a formal TOPICS + M statement is used or an alternative takes its place, Step 1 should lead the SR team to as nuanced a statement of the research problem as possible. The work in this step sets the stage for the remaining steps. For example, it helps the team to identify the best literature search terms and literature sources (e.g., especially grey literature sources that involve using sources other than electronic databases), to use more systematic searching to determine which studies will be included (and excluded) in the review, and to determine which features of the studies most need coding.

Selected popular structures for formulating questions systematic reviews as well as the currently proposed one, TOPICS + M.

NA = Not applicable to structure.

As part of completing Step 1, the SR protocol should be drafted for pre-registration, which details planned aims and analyses, before proceeding further (e.g., with PROSPERO or the Open Science Framework [OSF]). Doing so conveys a certain degree of trustworthiness to the SR, especially because systematic reviewing is essentially retrospective in nature ( Ioannidis, 2010 ): Review authors are often already aware of the individual findings of many of the studies they plan to include. Thoroughness may also help ward off competition from other teams: It is up to the SR team to be thorough and thoughtful in specifying primary and secondary research questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and planned analyses. Thus, the SR team should engage in most of the background work and piloting of screening and coding forms prior to beginning the review process, following contemporary protocol guidelines ( Lasserson et al., 2016 ; Moher et al., 2015 ) prior to registration. Accordingly, peer review prior to publication should also compare the submitted SR with any available pre-registered protocol.

3.2. Finding and selecting studies

Searches and selection criteria..

In Step 2, SR teams conduct systematic literature searches to find as many qualifying studies as possible ( Nakagawa et al., 2017 ). If the research statement is well developed, then, as noted, it economizes the search for studies and the process of determining which located studies match inclusion criteria and qualify for the review. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule: In the case of Lennon et al.’s (2012) HIV prevention SR, it was necessary to retrieve far more full-text reports for inspection, as these scholars realized that trials may not report mental health dimensions in their titles and abstracts.

Similarly, the rationale for each selection criterion should be clear from the background to the review and should also be carefully justified when reporting the SR. For example, review authors often decide to base inclusion criteria around the study design of included studies (e.g., including only RCTs), an approach that may not always be warranted: In every situation, the SR team must consider the review question and use knowledge of the existing body of evidence when making decisions about how to include and combine different study designs and make these assumptions clear to the reader.

Grey literature.

A number of disciplines have well-documented reporting biases such that studies with significant and positive effects are more likely to be submitted for publication and eventually published, and, as a result, the synthesis outcome is somewhat inflated ( Dwan et al., 2008 ; Easterbrook et al., 1991 ; Fanelli, 2012 ; Franco et al., 2014 ; Munafo et al., 2009 ; Polanin et al., 2017 ). Consequently, it has become a standard of high quality SRs to search for grey literature, unpublished work relevant to the defined TOPICS + M. Although some authors argue that grey literature is unpublished because it has lower quality, unless unpublished studies are gathered, it cannot be known whether in fact unpublished studies have low rigor; as well, in many disciplines, much published research has low rigor and, often, unpublished studies (e.g., theses, dissertations) have high quality ( Hanna, 2015 ). Thus, authors should attempt to be as comprehensive in their searches as possible and to search for and include grey literature, although how exhaustive the search is will depend largely upon available resources, and even when using comprehensive search practices, it is likely reviews still lack some relevant studies ( Delaney and Tamás, 2018 ). The scope of the literature search should be addressed in the conclusions and limitations section of the SR, especially if given decisions made by the review team, it is likely there is missing and relevant literature to the review; only review teams with incoming substantive expertise of the field can estimate how likely bias would be, and teams should always critically reflect on potential implications of their decisions.

Mono-language bias.

It may come as a surprise to native-English speakers, but much scientific literature appears in other languages: To the extent that studies appear in multiple languages, mono-language searches or inclusion criteria based on language of publication are a weakness, as there is no guarantee that results replicate across the cultures where these studies were conducted. For example, a meta-analysis found that a particular gene association reversed when Chinese literature was retrieved and compared to studies reported in English ( Pan et al., 2005 ). Similarly, a meta-review of 82 meta-analyses revealed that behavioural studies conducted in the U.S. achieve larger effect sizes than in other countries, whereas there was no difference for non-behavioural studies ( Fanelli and Ioannidis, 2013 ). SR teams should consider whether their research question is likely to have publications in other languages and may need to adapt their scope if they decide not to include non-English literature. In general, as with the collection (or not) of grey literature, SR teams should reflect on this decision and detail whether it influences the findings.

Necessary teamwork.

No matter how refined a research statement is, literature searches are nearly always highly time- and energy-dependent. Because the number and diversity of databases quickly changes, it has increasingly become a hallmark of high quality SRs that their teams include librarians and information retrieval specialists who are trained in systematic literature retrieval; doing so routinely improves and economizes searches. Team members should screen abstracts independently and in duplicate. If reliability is high on a randomly selected portion of the potential studies, then it is permissible to do single screening, which saves resources: The AMSTAR 2 tool suggests that there should be a kappa score between two independent reviewers of 0.80 or greater to ensure trustworthiness of decisions ( Shea et al., 2017 ). Although there has been no set standard for how large of a randomly selected portion to use, based on our experience, we would suggest examining the first 10% and then every 10% thereafter until high agreement (i.e., benchmark suggested by AMSTAR) is reached. Nonetheless, in some cases, this process may simply lead to the realization that all tasks must be done in duplicate in order to ensure trustworthiness of the findings. Another option is to use a liberal screening approach such that one person screens all potentially eligible studies and a second screener only reviews those that the first person excluded, to ensure the search does not exclude anything that should be included. We have emphasized the teamwork involved in successful SRs; committed, honest team members help to correct each other’s mistakes. Practically speaking, without duplicate effort, there is no way to report reliability.

The future of report screening.

In recent years, computer scientists are have developed automated search engines and screening tools ( Carter, 2018 ; Marshall et al., 2018 ; Przybyla et al., 2018 ; Rathbone et al., 2015 ). Following human interaction to train them, which again should utilize duplication of effort, these widgets then make fast work of abstract selection. One problem with this method is its technical demands ( Paynter et al., 2017 ). Another cost- and time-efficient method is crowdsourcing selection of literature using online workers ( Mortensen et al., 2017 ).

3.3. Coding studies for substantive and methodological features

A strong formulation of the research problem leads to coding methods that capture the most interesting aspects of the studies, those that the SR team expects will moderate effects. For example, SRs of interventions commonly examine which behaviour change techniques were tapped in an effort to improve participants’ health ( Michie et al., 2013 ); the dosage of treatment is another common dimension. A coding formulation should not overlook (a) items that tap risk of bias and/or methodological quality; and (b), descriptive features of studies that will accurately depict the underlying characteristics of included studies and may be helpful for post hoc observations. As much as possible, the authors should specify items for data extraction prior to reviewing the studies; then, they should pilot data extraction forms to ensure coders understand the coding dimensions and requirements. Some frameworks that could be useful tools to create a detailed data extraction form include PROGRESS-Plus for variables related to equity issues between/among included populations ( O’Neill et al., 2014 ), TIDieR for key intervention components ( Cotterill et al., 2018 ; Hoffmann et al., 2014 ) or the Behaviour Change Taxonomy and its associated coding system ( Michie et al., 2013 ), and the clinicaltrials.gov checklist for a fully-reported outcome measure (e.g., see https://prsinfo.clinicaltrials.gov/data-prep-checklist-om-sa.pdf ).

It is helpful to include a codebook along with the standardized form that details key definitions or operationalisations the coders will need to ensure accurate coding; software facilitates the process, especially with large SRs. As with screening, it is best to double-code independently and in duplicate and resolve discrepancies as they arise. Review authors should also consider what items may need to be coded qualitatively (e.g., using direct quotations from reports) and what content should be coded in a summary manner (e.g., using categorical response options). These strategies should be evaluated ahead of time by trying the dimensions on small (but diverse) samples of studies. Meeting often throughout this part of the review process will help ensure that data extraction mistakes are caught and addressed quickly. Finally, advances in artificial intelligence are beginning to economize these operations ( Sumner et al., 2019 ).

In science, generalizations of new knowledge depend on having valid observations in the first place, and it is well known that people routinely use misleading or false information (cf. De Barra, 2017 ; Ioannidis, 2017 ). Thus, if the methodological quality of studies is assessed, then the SR team has a means to determine if conclusions of the SR hinge on the inclusion of studies that lack rigor. Unfortunately, other than psychometric artefacts, which attenuate effect sizes ( Schmidt and Hunter, 2015 ), and bias introduced with p -hacking or selective reporting ( Kirkham et al., 2010a , b ; Rubin, 2017 ; Williamson et al., 2005 ), which tend to exaggerate effects, little is known about the effects of other methodological problems, such as confounds between groups randomly assigned to condition ( Higgins, 2008 ; Johnson et al., 2015 ; Valentine, 2009 ). Thus, it should be evident that even if a SR team limits a review to RCTs, there can still be flaws in individual RCTs due to individual research decisions or mistakes (e.g., poor blinding or allocation concealment, inadequate randomisation, other biases introduced during the process).

The SR team should use the most appropriate methodological quality instrument for the type of study designs that appear in their SR; multiple scales may be needed if the study design inclusion criteria are broad. It is best not to design new scales for this purpose, as there are many standardized and appropriate tools for various study designs and for treatments in particular disciplines. Even as early as 2003, there were nearly 200 tools available to evaluate non-randomized designs ( Deeks et al., 2003 ), let alone quality inventories for RCTs. Tools recommended for SRs focused on outcomes from intervention studies include the Cochrane Risk of Bias for RCTs ( Higgins et al., 2011 ) or the ROBINS-I tool for non-randomized studies ( Sterne et al., 2016 ) as these have been created to address the major issues relating to risk of bias in primary studies and, as such, are considered the gold-standard of risk of bias tools and are widely used.

Many meta-analyses create summative scales from the individual items assessing methodological quality, but this practice makes the operational specificity assumption, which is that the items have units that bear with equal weight, when it is possible that even one crucial flaw could invalidate a study ( Valentine, 2009 ). Thus, it is best to examine whether the specific, individual defects undercut conclusions ( Higgins, 2008 ; Johnson et al., 2015 ). If an intervention effect appears only in the weakest studies, then it undermines any conclusion that the intervention is efficacious. Thus, results from this analysis of risk of bias must be incorporated into the discussion of evidence of the effects. A tool to assist in this regard is the GRADE approach ( Balshem et al., 2011 , Canfield and Dahm, 2011 ), including the GRADE CerQUAL for qualitative meta-syntheses ( Lewin et al., 2015 ), which provide guidance for systematic assessment of the outcome in light of the quality of the evidence in the review and the potential areas of bias among individual studies. The GRADE approach emphasizes ratings based on studies’ limitations, consistency, and precision of outcome findings (i.e., directness of how well a study addressed questions of interest, and publication bias) and results in high, moderate, low or very low ratings of the quality of evidence for a particular outcome. Obviously, GRADE emphasizes exactly the factors that SR teams should be integrating in their SRs. Yet, without standardized tools such as GRADE, there is little systematic guidance for the presentation of conclusions and the result is that stakeholders could easily misread reports due to lack of precision (or even in some cases subjective reporting) on the part of the researcher ( Knottnerus and Tugwell, 2016 , Lai et al., 2011 ; Yavchitz et al., 2016 ). Thus, while the rigor of GRADE depends on how well it is applied, without such a standardized system, review authors can allow bias (e.g., significant results) to interfere with nuanced and accurate reporting.

3.4. Calculating effect sizes

SRs qualitatively or quantitatively pool results. A meta-analysis puts study outcomes on the same metric to pool results; effect sizes may examine associations between variables, mean levels of a phenomenon, or both. In a SR without meta-analysis that focuses on outcomes, qualitative descriptions of results replace the pooling of effect sizes, but authors should also present single effect sizes for each study or the available quantitative results from the reports.

Calculating effect sizes is a central problem when examining treatments with continuous outcomes (e.g., quality of life, depression scores, substance use), which generally requires use of the standardized mean difference ( SMD ) due to multiple continuous outcomes and a variety of measurement tools. In contrast, this issue is much less problematic in studies using dichotomous outcomes (e.g., abstinent, mortality rate) or those with correlational data. As we noted, the SMD especially becomes more complicated because of the myriad of details that studies report (or fail to report). One initial step is to reach out to authors to ask them to provide the team with the necessary data. Yet, when primary study authors are unavailable or unresponsive to requests for data, SR teams may not think creatively enough about what to do when the standard statistics, such as means and standard deviations, seem to be missing in study reports. There are many ways to get around poor primary study reporting: (a) Use figures, other results or test statistics (e.g., results from an F test; see the online effect size calculator ( Wilson n.d. )). (b) Extrapolate a matrix of correlations from structural equation results ( Kenny, 1979 ). (c) Estimate the mean and variance from the median, range, and sample size ( Hozo et al., 2005 ). (d) In studies that use analysis of variance (ANOVA), even if the report omits the critical comparison of conditions, it is still possible to determine a pooled standard deviation if other F tests are provided, along with relevant means; thus, if the two means to compare are available, an effect size may be calculated ( Cohen, 2002 , Johnson and Eagly, 2014 ). When in doubt, it is always advisable to consult with a statistician.

The foregoing strategies reveal that there are many ways to calculate effect sizes. When studies report multiple means of calculating effect sizes, all that have the same level of inferential information should be used (e.g., means and standard deviations and t or F tests), to triangulate on the best estimate. Continuous information is more accurate than categorical information; thus, means (e.g., levels of life satisfaction, depression) are better than count information (e.g., proportions recovering from illness). It is also preferable to re-calculate the effect sizes, rather than rely on the original study authors’ calculations, to make sure that the effect sizes and their signs are accurately coded. Note that including studies with weaker statistics is still considered preferable to dropping studies for being relatively inaccurate. Again, consulting with a statistician about problematic cases is always advisable. Then, sensitivity analyses evaluate whether these particular estimates are outliers or unduly influence the model.

After the calculation of effect sizes, the next consideration prior to analysis is whether the effect sizes need to be adjusted for small sample bias (which is conventionally the case for the SMD ), or to a metric that addresses coefficients with undesirable statistical properties (e.g., in the case of correlations transforming to Fisher’s z ), as well as how to identify and handle outliers. Additionally, once the chosen effect size is calculated, attention to the calculation of its standard error is the last important consideration before analysis; the standard error for each effect is an estimate of the degree of sampling error present and a variation of it is used as weights in meta-analytic statistics ( Borenstein et al., 2011 , Hedges and Olkin, 1985 ; Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). Note that the standard error is a gauge only of the potential for sampling error and not of other types of error (e.g., low methodological rigor; for more detail on such matters, see sources cited in Table 1 ).

3.5. Analysing the SR database

Analytic assumptions..

In classical meta-analysis, non-independence among studies in a review is another problem that might need to be handled at multiple stages in the review process. The first occurrence is when the effect sizes are calculated because non-independence, if ignored, can result in inaccurate study weighting. Non-independence may result because (a) studies have more than one relevant measure of an outcome; (b) because a comparison group is used more than once in calculating effect sizes (e.g., multiple treatment arms compared with a single control group); or (c) when primary studies do not appropriately adjust for clustering within their own sample (i.e., in the case of a cluster-RCT). Thus, it is important to attend to dependency by first examining how clustering was handled in any of the primary reports utilizing cluster-RCTs: Adjustments to the effect size standard error should be made if primary study authors did not attend to this issue ( Hedges, 2007 ). Regarding non-independence among studies in the sample due to multiple effect sizes per study, if there are sufficient studies, it is best to model the non-independence (e.g., using robust variance estimation (see De Vibe et al., 2017 ; Hedges et al., 2010 ); another approach is structural equation meta-analysis ( Cheung, 2014 )), rather than selecting one effect size or averaging similar effect sizes for each study. These strategies are particularly valuable when there are large numbers of studies available and are preferable to simply averaging effect sizes within studies, a solution that can lose valuable information. Whichever method is chosen to address non-independence among samples in the review, it should be documented.

Analyses should be conducted appropriate to the questions and the literature base. In the health sciences, research questions often address diverse samples, treatments, or environments, all of which may contribute to inconsistencies in results across studies. Consequently, models that follow random-effects assumptions are relatively conservative but typically the most appropriate modelling choice given the likely variability in health sciences questions, interventions, and populations, although there are cases where fixed-effect assumptions are better ( Borenstein et al., 2011 ). Others have argued for the use of unrestricted weighted least squares meta-regression to account for heterogeneity ( Schmid, 2017 , Stanley and Doucouliagos, 2015 ). Given the diversity of options available to synthesis authors, modelling choices should be explicitly stated, and justification should be provided. Yet, despite an increase in power due to pooling studies, many meta-analyses using random-effects models are in fact underpowered to detect effects because of the parameters needed to estimate between-study variance. Thus, power analysis should be considered in advance of undertaking a review of diverse literature. Additionally, any primary analysis must incorporate an assessment of heterogeneity and should consider publication or other reporting biases that could exist alongside substantive moderators.

In a SR without meta-analysis, qualitative descriptions of results replace analyses. SR teams may choose to omit a meta-analysis for several reasons: (a) if the literature is new and small (one cannot do a meta-analysis when there is only one study); (b) studies in the literature lack rigor; (c) the included studies are extremely different and the team has no hypothesized potential moderators; (d) if the review question centres on processes, theory development, research of a qualitative nature; or (e) the SR team lacks the statistical expertise to conduct a meta-analysis. It is important to note that simply lacking the expertise to conduct a meta-analysis is not adequate justification for conducting an outcomes-focused narrative review of a field that has sufficient primary study evidence for a quantitative analysis. Teams without such expertise should identify this need at the outset and set the scope of their SR accordingly, or, enlist the help of an expert meta-analyst early in the process. Authors must also carefully reflect on the potential study designs and areas for heterogeneity at the start of the review process (i.e., during protocol development) and attempt as much as possible to determine ahead of time whether a meta-analysis (versus a narrative review) will be possible. If, during the course of the review, the authors realize that a pooled synthesis is not possible or would not provide clear answers, authors may decide that it is better to map the existing research eligible for the review, rather than focus on outcome (effectiveness) data; however, this post hoc decision should be transparently reported with reasonable justification and all collected outcome data should still be reported in a standardized format (e.g., as effect sizes). That is, the judgement that “the studies were too clinically heterogeneous to combine” is an insufficient rationale for not conducting a meta-analysis. As with all research designs, the best design for the question of interest should be utilized in a synthesis endeavour, given the resources available.

The decision to conduct a meta-analysis–or a qualitative analysis–is one that review authors must consider and justify given the research question and scope. The larger the literature is, the more the risk rises that a reviewer may take shortcuts that reduce the accuracy of the conclusions reached; thus, a SR may fall prey to the same “cherry-picking” problems that vexed reviews before meta-analysis became commonplace: Selecting studies whose results support the SR author’s biases and views. Thus, SR teams need to erect barriers that prevent selectively presenting study findings.

Moderators of effects.

The fact that, in nearly every literature, study results are routinely highly variable led us to advocate in TOPICS + M a prion specification of moderators for substantive dimensions (or as sensitivity analyses). Meta-analyses have the best possibility of locating cross-study inconsistencies, because quantitative indexes have been developed to gauge it (see next sub-section, Heterogeneity ). Literally, these examine whether there is more variability in effect sizes than would be expected by sampling variance alone; that is, the null hypothesis is that there is homogeneity and, when the hypothesis is rejected, the statistical inference is that heterogeneity exists ( Borenstein et al., 2011 ; Hedges and Olkin, 1985 ). Heterogeneity, in turn, implies that there is more than one population effect at work in the literature, or that a range of population effects exists. In turn, a mean effect size for such a literature is not very precise and instead, moderators should be evaluated.

Reviewers can systematically examine heterogeneity by testing moderators driven by applicable theory and relevant research. In Step 1, SR teams specify moderators chosen for the analysis; unexpected moderators tested post hoc should be so identified for readers. It is important to remember what the moderator means in the meta-analytic context and interpret results appropriately. For example, a variable such as percentage of male participants is analysed at the study, not individual level; if gender is identified as a significant moderator of trial outcomes, then, outcomes improved to the extent that studies sampled larger portions of a certain gender (e.g., females). The SR team is not justified to infer that “this intervention worked better for females” only that it worked better for studies with larger proportions of female participants. If they have sufficient numbers of studies, SR teams should evaluate moderators that are significant in bivariate models in simultaneous, multiple-moderator models. Locating patterns whereby some moderators uniquely predict effect sizes potentially reduces confounding between predictors and thus yields a clearer picture of results ( Tipton et al., 2019 ). Similarly, SR teams should examine whether results hinge, either overall or by interaction with moderators, on the inclusion of lower quality studies; findings that hinge on studies with low rigor should be interpreted with appropriate caution ( Johnson et al., 2015 ; Valentine, 2009 ).

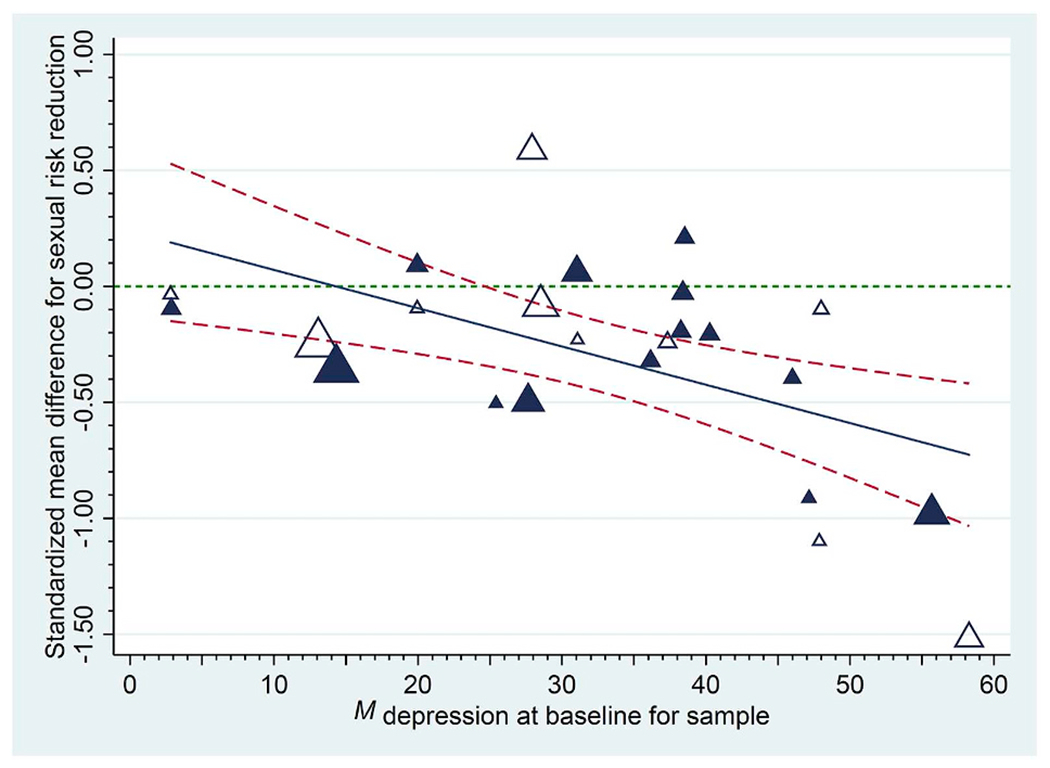

When reporting moderators, it is helpful to depict results in either graphical or tabled form. Johnson and Huedo-Medina (2011) introduced the moving constant technique, with which analysts use meta-regression models to create graphs or tables of estimated mean effect sizes plotted against moderator values, including confidence intervals, or confidence bands around the meta-regression line. This technique can also be used to estimate mean effect size values and confidence intervals at moderator values of interest for moderators that reached statistical significance. Specifically, analysts may move the intercept to reflect interesting points along or beyond a range of independent variable values. Returning to Lennon et al.’s (2012) meta-analysis of HIV prevention interventions for women, these scholars showed that trials succeeded better for samples with higher baseline depression: As Fig. 2 shows, on average, risk reduction was large and significant for samples with the highest mean levels of depression, whereas for samples with lower levels of depression, interventions failed to change risk. (Separate analyses also revealed that reducing depression was associated with greater risk reduction.) Results presented in this form help show at what levels of a moderator an effect exists. Returning to the significant gender moderator example above, now, we can answer the question of whether, on average, trials significantly succeeded for male vs. female samples. Such estimates, in turn, can be highly informative when interpreting the nature of the phenomenon being studied in the meta-analysis, especially when a comparison to an absolute or a practical criterion is important.

Empirical demonstration of the moving constant technique: Sexual risk reduction following a behavioural intervention as a function of each sample’s baseline depression. Sexual risk behaviour declined following the intervention at the last available follow-up to the extent that samples had higher levels of baseline depression (treatment [control] group effects appear as darker [white] triangles and the size of each plotted value reflects its weight in the analysis). The solid regression line indicates trends across initial levels of depression; dashed lines provide 95% confidence bands for these trends. Reproduced from Lennon et al. (2012) .

The moving constant technique also permits analysts to estimate confidence intervals for an effect size at particular values of one or more independent variables (and thus to avoid artificially dichotomizing continuous predictor variables). In multiple moderator models, an extension of the moving constant technique is to show what average effect appears for combinations of moderators. For example, MacDonald et al. (2016) showed that resistance exercise creates large to very large beneficial effects for the systolic blood pressure of (a) non-White samples (b) with hypertension at baseline, (c) who are not taking medications, and (d) who perform eight or more exercises per session. (Similar effects emerged for diastolic blood pressure.) Another reason analysts should emphasize the confidence intervals around such point estimates is because they are more conservative. In the MacDonald example just provided, their model estimated a 1.02 standard deviation average blood pressure improvement for resistance exercise, but the 95% confidence interval on this estimate was 0.67 to 1.36, so there is a considerable range.

When literature have sufficient size and spatial variability, spatiotemporal meta-analyses can incorporate ecological- and/or community-level variables in their models ( Johnson et al., 2017 , Marrouch and Johnson, 2019 ). For example, Reid et al. (2014) examined whether the success of HIV prevention interventions for African Americans depended on levels of prejudice these people experienced. In fact, interventions failed, on average, for trials conducted in relatively prejudiced communities and succeeded better to the extent that Whites were not prejudiced. Using spatiotemporal factors along with study-level factors can help diverse disciplines to converge, a practice that ought to be encouraged for a journal like Social Science & Medicine, which prides itself on its interdisciplinary nature. Of course, as Kaufman et al. (2014) recommended, SR teams may seek guidance from experts in multiple disciplines and also pursue ecological and/or spatiotemporal models of the effects in their reviews ( Johnson et al., 2017 ), though of course these matters should be considered at the outset, in Step 1.

Heterogeneity.

Heterogeneity in a review is one of the most important areas to assess and an area that is often ignored or, even worse, misinterpreted. We have already noted that its existence sharply challenges the interpretation of an overall mean effect size (in the case of a random-effects model, it literally implies a mean of means). The real question for meta-analyses is whether there is still large or significant heterogeneity remaining after applying moderators. Conventional practice is to use and report multiple assessments including I 2 , τ 2 , and Q (and its associated p -value), as there are a number of documented limitations with individual tests of heterogeneity. For example, although in theory I 2 does not depend on the number of studies and is easily interpretable on a scale of ~0–100% ( Higgins et al., 2002 , Higgins et al., 2003 ), I 2 is a relative rather than absolute measure of heterogeneity; it also increases with the inclusion of larger samples of studies and thus may artificially increase in a particular literature over time ( Borenstein et al., 2017 ; Rucker et al., 2008 ). Additionally, research has demonstrated that in meta-analyses with smaller k, I 2 can have substantial bias ( Von Hippel, 2015 ); for this reason, reporting of the random-effects variance, τ 2 , is also recommended ( Schwarzer et al., 2017 ). Similarly, Q values also vary by choice of measure of effect; thus, directly calculating I 2 from Q yields results that deviate from the theoretically intended values ( Hoaglin, 2017 ). I 2 has a limited maximum value (100%), but is literally based on Q , which has an infinite maximum value; consequently, I 2 is not quite linear, although a convention has emerged with 25% being small, 50% medium, and 75% large heterogeneity ( Higgins et al., 2003 ). Nonetheless, analysts should keep in mind that the inference of heterogeneity is a yes or no inference based on a significant test statistic.

Another consideration with heterogeneity is whether the heterogeneity may be attributed to one or more outliers included in the SR ( Viechtbauer and Cheung, 2010 ). If removal of one or two outlying effects markedly decreases heterogeneity, then the SR team can examine these as a post hoc effort to determine whether they differ in important respects from other studies. Alternatively, it may be that some moderator should have been coded but was missed when conceptualizing the review. Finally, outlying effects can be winsorized (e.g., reduced to a reasonable magnitude compared to other effects) so that they do not unduly influence results.

Publication bias.

Publication bias (viz. small-studies or reporting bias) refers to a tendency for certain findings to be published, generally those that reach statistical significance, rather than null, findings. There are multiple tests SR teams can use to assess the potential of this bias in a review; each has limitations and therefore SR teams are advised to triangulate data from multiple assessments. Although many sources recommend examining visual plots, such as funnel plots, this practice can be quite subjective and thus more critical sources have recommended quantitative approaches, such as regression-based assessments: Tests such as Begg’s ( Begg and Mazumdar, 1994 ), Egger’s ( Egger et al., 1997 ), and PET-PEESE ( Stanley and Doucouliagos, 2014 ) examine whether there is a skew to effects (such that smaller studies exhibit larger effects). It is important to realize that such tests generally assume a single population effect size; therefore, in the face of heterogeneity, inferences of publication bias are perilous. In parallel, the existence of publication bias can artificially restrict the range of known effect sizes, perhaps even to the point of (artificial) homogeneity. It is important to note that a number of reasons may drive the appearance of an asymmetrical funnel plot, including heterogeneity due to moderators ( Lau et al., 2006 ). Thus, SR teams must carefully consider how likely it is that reporting and publication bias exists in their particular field and the likely impact it has on the review. As well, we must caution against the use of Failsafe N, as it relies on arbitrary assumptions ( Becker, 2005 ).

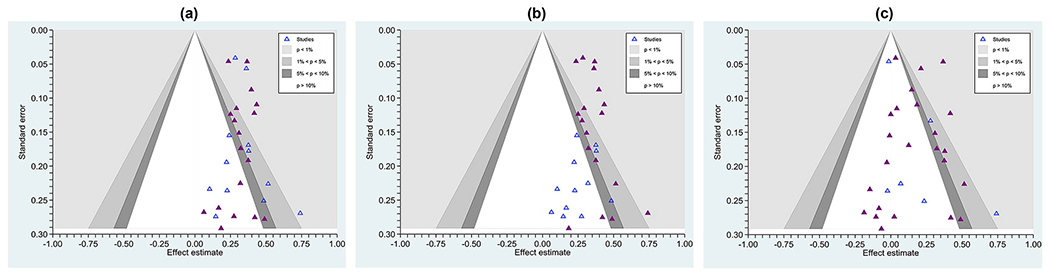

Many sources advocate direct tests of publication bias, such as comparing effects garnered from journal articles versus those from theses and dissertations (e.g., Card, 2015 , Johnson and Eagly, 2014 ), and we advocate the very practical strategy of examining whether null effects appear in peer-reviewed publications and whether grey literature studies routinely achieve significant effects. Contour-enhanced funnel plots can be a useful tool for this purpose, plotting effect sizes with differing symbols for publication status. Fig. 3 , Panel a, shows a literature in which study effects routinely reached statistical significance no matter whether published (solid dark blue markers) or not (grey markers). Panel b shows a literature in which the grey literature routinely does not reach significance; here is one with strong evidence of publication bias. Finally, Panel c shows a literature with heterogeneity, no matter whether grey or published studies are considered, and it is the goal of the SR team to find moderators of effects, if possible.

Contour-enhanced funnel plots showing effect sizes from three literature (a) one with no clear evidence of selective (e.g., publication) bias, as even published studies (solid triangles) commonly achieve null results and unpublished studies (hollow triangles) achieve statistically significant outcomes (this distribution is also homogeneous, τ 2 = 0.00047, I 2 = 0%); (b) one with marked evidence of selection bias, with only published studies routinely finding a significant effect and unpublished studies routinely finding non-significant effects ( τ 2 = 0.00047, I 2 = 0%); and (c), a literature with marked heterogeneity ( τ 2 = 0.0145, I 2 = 61%). The contours surrounding the null value show at which points individual effects reach significance. Effects in the white zone are statistically non-significant, where the significance level is set at p > . 05.

3.6. Interpretation and dissemination

In elaborating Steps 1 through 5, we have already offered much advice that is relevant to Step 6, interpretation and dissemination. Broadly speaking, the SR’s methodological operations need to be clearly stated and its key assumptions carefully defended. As Fig. 1 implies, performing Steps 1–5 with rigor logically eases matters of interpretation and dissemination. The review report should be considered as though it were a primary experiment: (a) What do readers need to know so that they could reproduce the results of this SR? (b) What about the methods should be related so that readers understand potential biases introduced by the review team during the review process?

Given the rising frequencies of meta-reviews, published SRs will likely be reviewed for best practice SR standards using standard review criteria (e.g., SAMSTAR 2: hea et al., 2017 ; risk of bias in systematic reviews [ROBIS]: Whiting et al., 2016 ). Because of potential feedback loops in the process ( Fig. 1 ) whereby the SR team serendipitously learns better strategies for reviewing the studies in question, it is incumbent on the team to report when, what, and why the process returned to an earlier step (e.g., because it was discovered that search terms omitted studies that would have qualified). The team must identify post hoc adjustments that occurred following registration and provide rationale for these deviations because it is not safe to assume that readers will compare a protocol to a published review. Transparency is important to reduce potential bias in reviews. For example, recent meta-reviews demonstrate that as many as 20–30% of systematic reviews are prone to selective inclusion and reporting of outcomes ( Kirkham et al., 2010a , b ; Mckenzie, 2011 ; Page et al., 2013 ; Tricco et al., 2016 ).

Although such information partially mirrors the PRISMA checklist, the checklist is formally a list of reporting standards. It does not directly necessarily address methodological quality. Indeed, Table 3 overlays the PRISMA checklist ( Moher et al., 2009 ) with an important, recently developed assessment of methodological quality for systematic reviews ( AMSTAR 2; Shea et al., 2017 ). There is only partial overlap: Thus, while authors may think they are adequately following SR standards when they “follow PRISMA standards,” they may miss some key areas for conducting a methodologically rigorous SR. Thus, we assert that merely following PRISMA reporting guidelines does not guarantee high quality.

Comparison of AMSTAR 2 with the PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews (SRs), ordered using AMSTAR 2’s items, and using the AMSTAR 2’s “yes” categories as high quality; this comparison also indicates the AMSTAR 2 items deemed critical by its authors (marked with ✪ ), as well as two that the current authors believe are also critical ( ✰ ).

Note. Omitted PRISMA items are stylistic and do not reflect on methodological features. NRSI = non-randomized studies of interventions. RoB = Risk of bias. SR = systematic review.

Designated critical domain of methodological quality by the AMSTAR 2 development team.

Designated a critical domain of methodological quality by the current authors (in addition to those the AMSTAR 2 team listed).

As Table 3 details, conclusions must take into account whether studies exhibit deficits in methodological quality. Limitations about the primary studies involved should primarily be discussed in the results section (e.g., when presenting risk of bias information) and how these influence conclusions to be made from the review or when discussing how primary study authors should do a better job of measuring and reporting certain variables (e.g., if evidence for an effect is only found in the weakest studies, then its existence is in considerable doubt). However, SR authors must also focus on the limitations introduced by the decisions they made or methods used: For example, perhaps there was not enough funding to employ a double-screener or perhaps the review team could use only one language for searches. Thus, review authors must thoughtfully consider how these decisions may (or may not) influence the implications from the review and discuss them for the reader.

Finally, in the discussion and concluding sections, audiences will benefit most if findings have been transformed into a meaningful metric as pooled effect sizes of a literature are not always intuitively meaningful in and of themselves. Thus, a SR should answer the question: What do these findings mean? For example, if the review assessed whether brief alcohol interventions were effective in reducing adolescent substance use, the outcome could be transformed into a clinically meaningful metric such as number of days’ reduction in use, rather than a standardized mean difference ( Hennessy and Tanner-Smith, 2015 ). Similarly, Macdonald et al. (2016) converted their standardized mean difference estimates for the impact of exercise into millimetres of mercury (Hg), the standard interpretive guide for clinicians. Other sources provide similar tips for presentations and help SR teams ponder their findings and what they imply for the domain being reviewed (e.g., Borenstein et al., 2011 ; Card, 2015 , Johnson and Eagly, 2014 ).

3.7. Re-analysis, development, or criticism

Some literature develop rapidly, outdating extant SRs, and making updated SRs valuable sooner. Alternatively, a SR team might theorize that dimensions that were not considered in a published SR might help explain observed heterogeneity; as long as the original SR’s methods were of high quality (see Tables 1 and 3 ), then the previous SR’s database, if available, may be reanalysed to evaluate these hypotheses, although of course, if the SR is dated, a new literature search should be performed along with Steps 3–7 as necessary. This recommendation takes advantage of data archiving; sharing databases is a way to save work and accelerate progress on the newest SR, but it assumes that the previous SR team has done an adequate job on their own journey through all the steps we have documented. Critics may target a SR that reaches conclusions they do not trust, but optimally, such critiques should take quantitative form, focusing on the degree to which SRs had rigor and pointing to areas where new, original research should be conducted, or, alternatively, new SRs.

To stay relevant to current conditions, many reviews should be updated regularly, depending on how rapidly new studies are emerging, what research question is addressed, and the nature of research in that scientific discipline. When to update a SR will hinge on the nature of the research question and the discipline. The Cochrane Collaboration even engages in “living systematic reviews” that are updated monthly ( Elliott et al., 2017 ), but this may not be appropriate for many types of research questions (e.g., in disciplines where treatment practices rarely change and where there have already been high quality SRs). However, evidence indicates that in some faster-moving fields (cardiovascular treatment research), 7% of reviews are out-of-date by publication and another 23% are out of date within two years of publication ( Shojania et al., 2007 ). Thus, it is up to individual review teams to have a sense of when an update will be appropriate.

4. Conclusions

In this article, we have endeavoured to provide best practice recommendations for research synthesis, which Table 1 summarizes as brief “dos and don’ts”. We highlighted a number of tools to guide researchers in the practice of research synthesis, although it is worth noting that these quality inventories have imperfections, but also represent a best-of-science approach at the present time. There is no doubt that we will see improvements emerge in the coming years and decades. As Shadish and Lecy (2015) concluded, meta-analysis is one of the central methodological developments in science, or, in their more dramatic terms, the spark of its own big bang. Nonetheless, the entire scientific community must continually take steps to ensure the highest scientific rigor in the SR process and in reporting and consuming results from systematic reviews. As we have argued in this article, when done with great rigor, SRs can yield great insights, relevant both to science and practice. They can also point the way to future studies that are optimized to fill gaps in the evidence base; in this way, well-done SRs ought to improve the efficiency of science. When a SR targets an important literature with the best known methods, the results can become a definitive statement that guides future research and policy decisions for years to come.

Acknowledgments

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Science of Behavior Change Common Fund Program facilitated preparation of this article through an award administered by the National Institute on Aging (a sub-contract from U.S. PHS grant 5U24AG052175). We thank Rebecca L. Acabchuk, Julie M. Brisson, Chris S. Elphick, Eliza Grames, and Catherine Panter-Brick for constructive feedback on earlier drafts; we also thank Ilinca C. Johnson for generating the acronym TOPICS + M (see text).

- Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Meerpohl J, Norris S, 2011. Grade guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64 (4), 401–406. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bayes T, Price R, Canton J, 1763. An Essay towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Becker BJ, 2005. Failsafe N or file-drawer number. In: Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M (Eds.), Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. Wiley Chichester, England, pp. 111–125. [ Google Scholar ]

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M, 1994. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50 (4), 1088–1101. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Booth A, 2006. Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice. Libr. Hi Tech 24 (3), 355–368. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR, 2011. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borenstein M, Higgins JPT, Hedges LV, Rothstein HR, 2017. Basics of meta-analysis: 12 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 8 (1), 5–18. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Canfield SE, Dahm P, 2011. Rating the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using GRADE. World J. Urol. 29 (3), 311–317. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Card NA, 2015. Applied Meta-Analysis for Social Science Research. Guilford Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter BU, 2018. Single screen of citations with excluded terms: an approach to citation screening in systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 7 (1) 111-018-0782-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chalmers I, Hedges LV, Cooper H, 2002. A brief history of research synthesis. Eval. Health Prof. 25 (1), 12–37. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheung MW, 2014. Modeling dependent effect sizes with three-level meta-analyses: a structural equation modeling approach. Psychol. Methods 19 (2), 211–229. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen BH, 2002. Calculating a factorial ANOVA from means and standard deviations. Understand. Stat.: Statistical Issues in Psychology, Education, and the Social Sciences 1 (3), 191–203. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A, 2012. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 22 (10), 1435–1443. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cotterill S, Knowles S, Martindale A, Elvey R, Howard S, Coupe N, Wilson P, Spence M, 2018. Getting Messier with TIDieR: Embracing Context and Complexity in Intervention Reporting. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Barra M, 2017. Reporting bias inflates the reputation of medical treatments: a comparison of outcomes in clinical trials and online product reviews. Soc. Sci. Med. 177, 248–255. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Vibe M, Bjørndal A, Tipton E, Hammerstrøm KT, Kowalski K, 2017. Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) for improving health, quality of life, and social functioning in adults. Campbell Syst. Rev. 11. 10.4073/csr.2017.11. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deeks J, Dinnes J, D’amico R, Sowden A, Sakarovitch C, Song F, Petticrew M, Altman D, 2003. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol. Assess. 7 (27) iii–x, 1-173. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Delaney A, Tamás PA, 2018. Searching for evidence or approval? A commentary on database search in systematic reviews and alternative information retrieval methodologies. Res. Synth. Methods 9 (1), 124–131. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Denyer D, Tranfield D, Van Aken JE, 2008. Developing design propositions through research synthesis. Organ. Stud. 29 (3), 393–413. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan AW, Cronin E, Decullier E, Easterbrook PJ, Von Elm E, Gamble C, Ghersi D, Ioannidis JP, Simes J, Williamson PR, 2008. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS One 3 (8), e3081. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR, 1991. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 (8746), 867–872. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ebrahim S, Bance S, Athale A, Malachowski C, Ioannidis JP, 2016. Meta-analyses with industry involvement are massively published and report no caveats for antidepressants. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 70, 155–163. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Egger M, Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C, 1997. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 315 (7109), 629–634. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliott JH, Synnot A, Turner T, Simmonds M, Akl EA, Mcdonald S, Salanti G, Meerpohl J, Maclehose H, Hilton J, Tovey D, Shemilt I, Thomas J, Living Systematic Review Network, 2017. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction-the why, what, when, and how. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 91, 23–30. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- European Food SA, 2010. Application of systematic review methodology to food and feed safety assessments to support decision making. Efsa guidance for those carrying out systematic reviews. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. J. 8 (6), 1–89. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fanelli D, 2012. Negative results are disappearing from most disciplines and countries. Scientometrics 90 (3), 891–904. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fanelli D, Ioannidis JP, 2013. US studies may overestimate effect sizes in softer research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 (37), 15031–15036. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Franco A, Malhotra N, Simonovits G, 2014. Social science. Publication bias in the social sciences: unlocking the file drawer. Science 345 (6203), 1502–1505. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garner P, Hopewell S, Chandler J, Maclehose H, Schünemann HJ, Akl EA, Beyene J, Chang S, Churchill R, Dearness K, Guyatt G, Lefebvre C, Liles B, Marshall R, Martínez García L, Mavergames C, Nasser M, Qaseem A, Sampson M, Soares-Weiser K, Takwoingi Y, Thabane L, Trivella M, Tugwell P, Welsh E, Wilson EC, 2016. When and How to Update Systematic Reviews: Consensus and Checklist. British Medical Journal Publishing Group. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glass GV, 1976. Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educ. Res. 5 (10), 3–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grant MJ, Booth A, 2009. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 26 (2), 91–108. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanna JM, 2015. The Quality of Education Leadership Doctoral Dissertations in the United States: an Empirical Review. Doctoral Dissertation edn. Marshall University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haynes RB, 2006. Forming research questions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 59 (9), 881–886. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hedges LV, 2007. Effect sizes in cluster-randomized designs. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 32 (4), 341–370. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hedges LV, Olkin I, 1985. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press Inc, Orlando FL, USA. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hedges LV, Tipton E, Johnson MC, 2010. Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Res. Synth. Methods 1 (1), 39–65. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hennessy EA, Johnson BT, Keenan C, 2019. Best practice guidelines and essential steps to conduct rigorous and systematic meta-reviews. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being (in press). [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hennessy EA, Tanner-Smith EE, 2015. Effectiveness of brief school-based interventions for adolescents: a meta-analysis of alcohol use prevention programs. Prev. Sci. Official J. Soc. Prev. Res. 16 (3), 463–474. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins JP (Ed.), 2008. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 5 edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester. [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D, 2002. Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 7 (1), 51–61. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG, 2003. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 327 (7414), 557–560. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA, Cochrane Bias Methods Group and Cochrane Statistical Methods Group, 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 343, d5928. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoaglin DC, 2017. Practical challenges of I(2) as a measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 8 (3), 254. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoffmann T, Glasziou P, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman D, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb S, DIXON - Woods M, Mcculloch P, Wyatt J, Chan A, Michie S, 2014. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Br. Med. J. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I, 2005. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 5 13-2288-5-13. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ioannidis JP, 2010. Meta-research: the art of getting it wrong. Res. Synth. Methods 1 (3–4), 169–184. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ioannidis JP, 2016. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 94 (3), 485–514. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ioannidis JP, 2017. Does evidence-based hearsay determine the use of medical treatments? Soc. Sci. Med. 177, 256–258. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Joanna Briggs Institute, 2011. In: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2011 Edition. University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson BT, Eagly AH, 2014. Meta-analysis of social-personality psychological research. In: Reis HT (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology, second ed. Cambridge University Press, London, pp. 675–707. [ Google Scholar ]