Chapter 9: Race and Ethnicity

Theories of racial inequality, learning outcomes.

- Describe functionalist views on race and ethnicity

- Describe conflict theorists’ views on race and ethnicity

- Explain symbolic interactionist views on race and ethnicity

- Explain and differentiate between theories of prejudice

We can examine issues of race and ethnicity through three major sociological perspectives: functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. As you read through these theories, ask yourself which one makes the most sense and why. Do we need more than one theory to explain racism, prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination?

Figure 1 . The 1950s waved in a flurry of theories surrounding prejudice in the wake of the Holocaust. Some of these were psychological theories, which focused on how an individual may come to develop, or not develop, prejudices. In his book, The Authoritarian Personality (1950), psychologist Theodor Adorno (in the foreground on the right of this photo) concluded that excessively strict authoritarian parenting caused children to feel immense anger towards their parents, but instead of confronting their parents, they idolized authority figures. (Photo courtesy of Jeremy J. Shapiro/Wikimedia Commons)

Psychological Theories of Prejudice

Scholars in the 1950s produced a number of theories addressing racial, ethnic, and nationalist prejudices in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Some of these were psychological theories, which focused on how an individual may come to develop, or not develop, prejudices. In his book, The Authoritarian Personality (1950), Theodor Adorno concluded that excessively strict authoritarian parenting caused children to feel immense anger towards their parents, but instead of confronting their parents, they idolized authority figures. Adorno said this led to increased levels of prejudice and the likelihood for these people to feel more connected to what he called the “F-scale,” (a pre-fascist personality), or to right-wing ideologies.

Psychologist Gordon Allport developed the contact hypothesis or inter-group contact theory in the 1950s, which posits if two groups with equal status and common goals come together, with cooperation, structural supports (i.e., existing laws or customs), and interpersonal communication, they can reduce stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination.

According to Henri Tajfel’s social identity theory (1979), people examine their own identity in light of perceived group membership. He says that we tend to increase our self-image by enhancing the status of the group to which we belong. Therefore, we divide the world into “them” and “us” or in-groups and out-groups with heightened prejudicial attitudes toward the out-groups.

Sociological Theories of Prejudice

Functionalism.

In the view of functionalism, racial and ethnic inequalities must have served an important function in order to exist as long as they have. This concept, of course, is problematic. How can racism and discrimination contribute positively to society? A functionalist might look at “functions” and “dysfunctions” caused by racial inequality. Nash (1964) focused his argument on the way racism is functional for the dominant group; for example, suggesting that racism morally justifies a racially unequal society. Consider the ways in which slave owners justified slavery in the Antebellum South, by suggesting black people were fundamentally inferior to whites, that they preferred slavery to freedom, that many were “like family,” and/or that the Bible justified slavery. Today, we can look at how people explain or justify racial inequalities in the criminal justice system (“Black and Brown men commit more crimes”) or racially segregated neighborhoods (“people choose where they live”) or shooting of unarmed people of color (“they appeared threatening” or “I was protecting myself or my neighborhood”).

Another way to apply the functionalist perspective to racism is to discuss the way racism can contribute positively to the functioning of society by strengthening bonds between in-group s members (dominant group) through the ostracism of out-group members (minority group members). Consider how a community might increase solidarity by refusing to allow outsiders access. For example, gated communities or neighborhoods with covenants might include no-rent clauses, which can have a de facto (in fact) discriminatory effect although they are not du jure (by law) discriminatory. Additionally, “Not in My Backyard” or NIMBY groups often are effective at limiting developments that could be viewed as reducing one’s property value. These movements and restrictive covenants are also “inescapably, about race” [1]

Conflict Theory

Conflict theories are often applied to inequalities of gender, social class, education, race, and ethnicity. A conflict theorist would examine struggles between the white ruling class and racial and ethnic minorities and use that history to analyze everyday life for racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S., paying special attention to power and inequality. Prejudice is a tool for maintaining power, and in many cases throughout United States history, prejudicial policies have become laws. The years since the Civil War have showed a pattern of attempted disenfranchisement, with gerrymandering (redrawing congressional districts to favor one political party over another) and voter suppression efforts, such as voter ID laws, aimed at predominantly minority neighborhoods. In the late nineteenth century, the rising political power of blacks after the Civil War resulted in draconian Black Codes and Jim Crow laws that severely limited black political and social power.

Vivien Thomas (1910–1985), the black surgical technician who helped develop a groundbreaking technique that saves the lives of “blue babies,” was classified as a janitor for many years, and was paid as such, despite the fact that he was conducting complicated surgical experiments. The popular film Hidden Figures (2016) shed light on the unrecognized work that black women did for NASA during the Space Race in the 1960s. It highlights many of the institutional discriminations that women of color faced, like being denied admission to study calculus and advanced mathematics, being overlooked for supervisory roles, and suffering the effects of Jim Crow segregation in the workplace.

Feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990) elaborated on ideas related to the inseparability of various social characteristics in intersection theory , or intersectionality. The term was first used by Columbia Law Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in a 1980 paper to describe the oppression of black women and how their experiences during the feminist movement were uniquely different from the mainstream feminist movement, which mostly represented middle-class white women. Intersection theory suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other attributes. When we examine race and how it can bring us both advantages and disadvantages, it is important to acknowledge that the way we experience race is shaped, for example, by our gender and class. Multiple layers of disadvantage intersect to create the way we experience race. For example, if we want to understand prejudice, we must understand that the prejudice focused on a white woman because of her gender is very different from the layered prejudice focused on a poor Asian woman, who is affected by stereotypes related to being poor, being a woman, and to her ethnic status.

Symbolic Interactionism

As discussed in the opening module, W.E.B. DuBois was one of the first sociologists to examine race and double consciousness (the feeling that one’s identity is divided because of race) and how that influences the sense of self. For symbolic interactionists, race and ethnicity provide strong symbols as sources of identity.

In fact, some interactionists propose that the symbols of race, not race itself, are what lead to racism. Famed Interactionist Herbert Blumer (1958) suggested that racial prejudice is formed through interactions between members of the dominant group; without these interactions, individuals in the dominant group would not hold racist views. These interactions contribute to an abstract picture of the subordinate group that allows the dominant group to support its view of the subordinate group, and thus maintains the status quo. An example of this might be an individual whose beliefs about a particular group are based on images encountered through popular media, which are then unquestionably believed because the individual has never personally met a member of that group.

Another way to apply the interactionist perspective is to look at how people define their races and the race of others. As we discussed in relation to the social construction of race, did Latinos “become White” because the Census removed the Hispanic category as a race? Are Arab-Americans White? What does it mean to be biracial? We discussed that President Obama is considered the “first Black President” and sometimes the “first African American President” even though his mother was white, his father was Kenyan, and the 44th President of the United States grew up surrounded by Hawaiian and Asian culture in Honolulu.

Sociologists like Kathleen Blee have studied racism (Blee studied women in hate groups) and found that racism is learned . This is supported by other social psychology experiments, and Blee reached her conclusions by conducting life history interviews with women in white supremacist groups. She found that most women were not racist when they joined the group; rather, they learned to be racist.

Culture of Prejudice

Culture of prejudice refers to the theory that prejudice is embedded in our culture. We grow up surrounded by images of stereotypes and casual expressions of racism and prejudice. Consider the casually racist imagery on grocery store shelves or the stereotypes that fill popular movies and advertisements. It is easy to see how someone living in the Northeastern United States, who may not know any Mexican Americans personally, might gain a stereotyped impression from such sources as Speedy Gonzalez or Taco Bell’s talking Chihuahua. Because we are all more or less exposed to these images and thoughts, it is impossible to know to what extent they have influenced our thought processes.

- Badger, E. 2018. "How 'Not in My Backyard' Became 'Not in My Neighborhood.'" New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/03/upshot/zoning-housing-property-rights-nimby-us.html . ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Introduction to Theories of Racial Inequality. Authored by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Theories of Race and Ethnicity. Authored by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:sa__n8SF@4/Theories-of-Race-and-Ethnicity . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 February 2021

The correct way to test the hypothesis that racial categorization is a byproduct of an evolved alliance-tracking capacity

- David Pietraszewski 1

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 3404 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

5750 Accesses

11 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

The project of identifying the cognitive mechanisms or information-processing functions that cause people to categorize others by their race is one of the longest-standing and socially-impactful scientific issues in all of the behavioral sciences. This paper addresses a critical issue with one of the few hypotheses in this area that has thus far been successful— the alliance hypothesis of race —which had predicted a set of experimental circumstances that appeared to selectively target and modify people’s implicit categorization of others by their race. Here, we will show why the evidence put forward in favor of this hypothesis was not in fact evidence in support of the hypothesis, contrary to common understanding. We will then provide the necessary and crucial tests of the hypothesis in the context of conflictual alliances, determining if the predictions of the alliance hypothesis of racial categorization in fact hold up to experimental scrutiny. When adequately tested, we find that indeed categorization by race is selectively reduced when crossed with membership in antagonistic alliances—the very pattern predicted by the alliance hypothesis. This finding provides direct experimental evidence that the human mind treats race as proxy for alliance membership, implying that racial categorization does not reflect attention to physical features per se, but rather to social relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Neural dynamics of racial categorization predicts racial bias in face recognition and altruism

A systemic approach to the psychology of racial bias within individuals and society

Covariation in the recognition of own-race and other-race faces argues against the role of group bias in the other race effect

Introduction.

Race occupies a central place in the history of the behavioral and cognitive sciences. Few other real-world phenomena can claim to have sustained the attention of the entire field throughout its varied history. Indeed, views of what race is and how to study it reflect the changing views of what the mind is and how to study it: from cataloguing what people associate with race 1 , to viewing the representation of race as an example of perceptual and semantic shortcutting 2 , 3 , and—with the advent of the cognitive revolution—as either a heuristic or bias 4 , or as an example of the intrinsically-evaluative nature of human cognition 5 .

A watershed moment for understanding the psychology of race perception and categorization occurred in 2001 with the publication of the paper, “Can race be erased?” by Kurzban and colleagues 6 . This paper was important for two reasons. One, it was the first time that a group of researchers had reported a successful experimental decrease in participants’ categorization of others by their race. While previous studies had found it trivially-easy to reduce racial stereotyping (the application of content associated with a category to a particular person), there was no known manipulation that had any effect on the process of racial categorization itself (that is, on the process of assigning a person to that social category in the first place 7 , 8 ). The discovery of a successful manipulation suggested that a new and fundamental insight about the psychology of racial perception and categorization had been uncovered.

Second, the paper demonstrated the utility of adopting an evolutionary approach. The successful manipulation had been discovered by considering what functions would be likely to exist within the mind, given a history of evolution. In particular, Kurzban et al. reasoned that because racial differences are evolutionarily-novel, racial categorization is not likely to be a dedicated function of the mind’s information-processing. Rather, it is likely to be a byproduct. The hypothesis considered by Kurzban et al. was that perhaps racial categorization is a byproduct of an ability to track alliances—something that would be selected for over evolutionary time. Tracking alliances requires (i) representing the units of coordination, cooperation, and competition that exist in one’s social world, and (ii) assigning individuals to these units, as a way to predict who will be affiliated with whom 9 , 10 .

Kurzban et al. reasoned that perhaps cognitive systems with these functions might, as a byproduct of their operation, also pick up on physical traits that tend to correlate with such patterns of coordination, cooperation, and competition in one’s local social ecology. If true, then this would mean that people categorize by their race because of exposure to racially-segregated and discriminatory social ecologies 11 , 12 . Race would then serve as a proxy to alliance membership 6 , 9 . We will refer to this as the alliance hypothesis of race.

Crucially, the alliance hypothesis suggests an experimental manipulation that should in fact modify categorization by race: If one can show that race—which presumably has a high prior of being predictive of how people are likely to interact and get along with one another for participants—is shown to be no longer predictive of who is allied with whom in an ongoing interaction, then its psychological importance should be reduced. Consequently, its use as an implicit basis of categorizing people should be reduced or abandoned, particularly when a new basis of predicting alliances is presented.

The Kurzban et al. paper is widely understood as testing and providing support for this prediction of the alliance hypothesis, utilizing the same paradigm that had previously found invariant categorization by race: the memory confusion paradigm (see Box 1 ). In their study, participants observed an antagonistic interaction between the members of two different basketball teams, each of whom supported one another while threatening and mocking the members of the other team. Such behaviors, by hypothesis, should engage the mind’s alliance-tracking. Participants were therefore predicted to categorize the interactants according to their team membership.

The memory confusion paradigm.

Moreover, and importantly, there were an equal number of Black and White players on each team. If the alliance hypothesis is correct, then this manipulation should reduce categorization by race: If the mind attends to race as a cue to how individuals are likely to interact and get along with one another, then showing that race is not predictive of such relationships should reduce the relative importance of race (at least temporarily). This reduction should then be reflected in lowered levels of categorization.

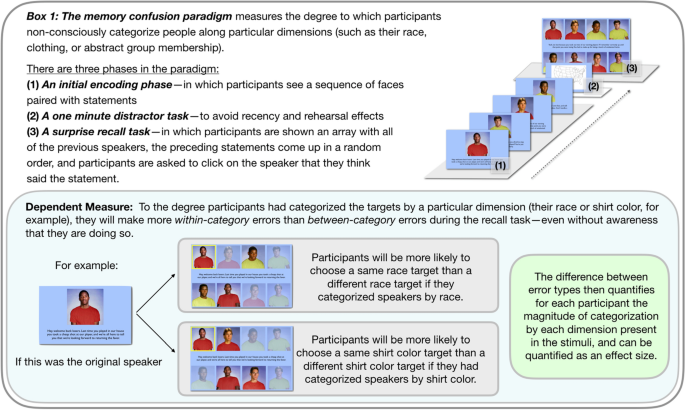

In fact, such a reduction in categorization by race was found in Kurzban et al.—specifically, between two different between-subjects manipulations: one in which team membership was not marked by team jersey color ( verbal only ), and a second condition in which jersey color was added to mark team membership (+ shared appearance ). The left side of Fig. 1 depicts (1) an increase in team categorization and (2) a decrease racial categorization across these two conditions (the y-axis describes the magnitude of categorization as determined by patterns of errors in the memory confusion paradigm):

Data reported in Kurzban et al. (2001). Categorization effect size describes the degree to which participants within each condition made more within-category memory errors than between-category memory errors. The effect size is calculated as the difference in means weighted by the variance within those means, and is standardized to range between 0 and 1.

The reduction in racial categorization depicted on the left side of Fig. 1 seems to be consistent with the alliance hypothesis of race. However, a counterhypothesis remains: Perhaps the reduction in race reflects an attentional shift, such that any non-relevant category would also be reduced under the same circumstances. Such a counterhypothesis would predict that age and sex (which are not hypothesized to be intrinsically alliance cues) will also be reduced if place in the same experimental context. The alliance hypothesis, in contrast, predicts that racial categorization will be differentially reduced compared to these other categories. In particular, there are good reasons to suspect that there are dedicated procedures in the mind for attending to both age and sex, as both would have been enduring features of conspecifics within ancestral environments, unlike race. The right side of Fig. 1 depicts Kurzban et al.’s test against this counterhypothesis. In this set of conditions, the same between-subject manipulation that had been applied to race was now also applied to sex. As shown, categorization by sex was slightly lowered, but not quite as much as the reduction in race, consistent with the alliance hypothesis.

This Kurzban et al. study is widely-regarded both within and outside of psychology as demonstrating (1) that the human mind spontaneously keeps track of the coalitional alliances of others (that is, it keeps track of who is on whose side in a conflict), and (2) that racial categorization is a byproduct of this coalition-tracking ability 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . Indeed, it is one of the most frequently-cited empirical findings within Evolutionary Psychology and about the psychology of race in general (cited over 1000 times as of the writing of this paper).

Subsequent studies have been conducted to test the alliance hypothesis —for example, in the context of cooperation, rather than antagonism 17 , and also with political affiliations 18 —but these have been largely seen by the scientific community as secondary, follow-up studies. The original Kurzban et al. study is still considered by many to be the primary source of evidence for the hypothesis. It is continually and universally-cited as providing evidence in support of the hypothesis 19 , 20 —such that any issues with the Kurzban paper are seen as grounds for dismissing the alliance hypothesis in general 21 . As the Kurzban et al. paper goes, so goes the evidence for the alliance hypothesis itself.

Our first goal here is to explain why, in the fullness of time, we now know this to not be true. Although these results of Kurzban et al. seem promising, there is a problem with this study design—a problem that has not been noticed in the over one thousand times that the paper has been cited, nor in replication attempts 22 , and thus has not yet been adequately addressed 17 , 18 . The problem is that this study design is not even in principle capable of testing the primary predictions of the alliance hypothesis.

In particular, there are two primary predictions of the alliance hypothesis:

Categorization by a now-relevant alliance membership (e.g., team membership) will occur.

Racial categorization will be differentially lowered when it is shown to be no longer predictive of alliance membership (i.e., when it is crossed with team membership, such that race no longer predicts who is on who’s side).

The problem with the Kurzban et al. study design is that in order to test the second prediction, one would need to know (1) what level of racial categorization one finds in the absence of any alliance information, and then (2) compare that to the level of racial categorization that one finds when race is crossed with team membership. The Kurzban et al. paper is frequently misunderstood as doing this very thing, but this not what was done.

Instead, what was compared across conditions was the effect adding a visual marker of team membership —not of adding team membership itself. In other words, (and as can be seen in Fig. 1 above) in both between-subjects conditions (that is, the verbal only and + shared appearance conditions) race was always crossed with team membership. In both conditions the team membership of each player was always clearly discernible based on what each player said and the order in which their photo appeared, as the conversation always alternated back-and-forth between members of the two different teams. This means that in both conditions, it was always clear to participants that race was crossed with team membership.

Consequently, there was never any manipulation of whether or not race was crossed with team membership; this was held constant, rather than varying across conditions. Yet it is exactly this manipulation—comparing race on its own to when race is crossed with team membership—that is required to test the primary prediction that race will be lowered when crossed with alliance membership. It is also this manipulation that one must look at when testing whether race will be lowered more so than will other social categories, such as sex or age. Yet no such comparison was ever done in Kurzban et al. Therefore, there is no way to evaluate what the impact of crossing race with alliance membership is—even though this is the primary prediction of the alliance hypothesis.

Moreover, the evidence for the differential reduction in race—compared in this case to categorization by sex—was weak in the findings of Kurzban et al. Importantly, one cannot make much of the fact that the absolute levels of categorization by sex are higher than are absolute levels of categorization by race in the data. What we know from past studies is that categorization by sex is typically higher than is categorization by race 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 . Furthermore, we know that the absolute level of categorization within these kinds of categorization studies is a function of the particulars of the study implementation details (roughly, in some studies one finds that the effect sizes for important social categories are large, others medium, but in all cases the ordinal relationship between, for example, sex versus race remains). In other words, one should not look at the Kurzban data with an implicit view that the levels of categorization by race and sex would have been equally-high if only the experimental contexts had not been coalitional. But unfortunately, this is how the data are often interpreted.

What this all means is that the informative result in Kurzban et al. is the change in categorization across the two experimental conditions, not the absolute value of categorization. And it is here that we find the mixed results: Yes, descriptively categorization by race was lowered more than was sex. But was there a strong differential reduction in race compared to sex? Here, different researchers looking at these same data may reasonably arrive at different conclusions. On balance, the data are certainly suggestive of a differential effect on race, but not particularly conclusive. However, even if the data were conclusive, this would still only be a differential effect of race as a consequence of shirt color, not team membership. We are then back to the more fundamental issue that even if we do interpret the reduction in race as stronger than the reduction in sex, we are still looking at a reduction caused by something other than what the alliance hypothesis predicts. Namely, shirt color as opposed to team membership.

The upshot of all of this is that what we can conclude, based on the Kurzban et al. data, is that racial categorization is reduced. But we cannot make any inferences that this was due to race being crossed with alliance membership. And we certainly cannot make any inferences based on these data that racial categorization is a consequence of alliance categorization. (Moreover, it has also come to light that an error correction used in prior memory confusion paradigm studies was faulty, leading to biased effect size estimates 27 , 28 . The data reported in Kurzban et al. are also subject to this problem. Consequently, we cannot even be confident in the results reported therein.)

In sum, then, the most-cited source of evidence in support of the alliance hypothesis of race—that an antagonistic sports team context engages alliance-tracking and causes a reduction in categorization by race—is in fact not an adequate test of the hypothesis. This leaves an uncomfortable gap in our knowledge: If an antagonistic context does not in fact produce the pattern of results predicted by the alliance hypothesis, then the hypothesis would be put into jeopardy. Although there has been subsequent work adequately testing the hypothesis in the context of cooperation and coordination 17 , 18 , a non-result in the context of antagonism when adequately tested would militate against the hypothesis, and would suggest that these other results may be due to more domain-general effects 18 .

Consequently, we ran and report here a study which provides the first adequate test of the alliance hypothesis in the context of conflict. Critically, the study here (1) establishes a baseline level of categorization by race when is it not yet crossed with any team (alliance) membership, and then (2) compares that level of categorization by race to a condition in which race is now crossed with team membership. This comparison then serves as the critical measure of what happens to racial categorization as a consequence of showing that race is no longer predictive of alliance membership.

In order to test the prediction that racial categorization will be more affected by such a manipulation than will other categories, the same comparison was also done with sex. Categorization by sex was measured at a baseline level and then again when sex was crossed with team membership. If the alliance hypothesis of racial categorization is correct, any reduction in categorization by sex across these conditions should then be less than the reduction in race.

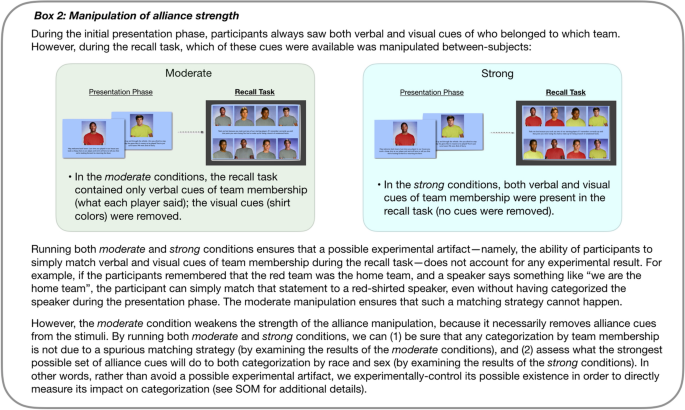

The following is a rough overview of the experimental design (for details, see method section): In the conditions featuring team membership, an antagonistic encounter between the members of two sports teams was presented. On each team there were either an equal number of Black and White or male and female players. Team membership could be inferred based on both verbal cues (i.e., what each player said) and also visual cues (shared shirt colors). The conditions measuring baseline levels of race and sex categorization were as closely matched to these team conditions as possible—featuring the exact same photo stimuli (i.e., the same faces and shirt color differences) and closely-matched statements. However, all statement content that would indicate that these were two different sports teams interacting was removed (see SOM for details). Finally, within the conditions featuring team membership, there were additional manipulations of both the nature of the sport (either basketball or soccer/European football) and the strength of the team membership (alliance) cues present during the categorization task (see below for details). These additional conditions provided both a within-study replication and a more fine-grained measurement of the effect of crossing race and sex with team membership.

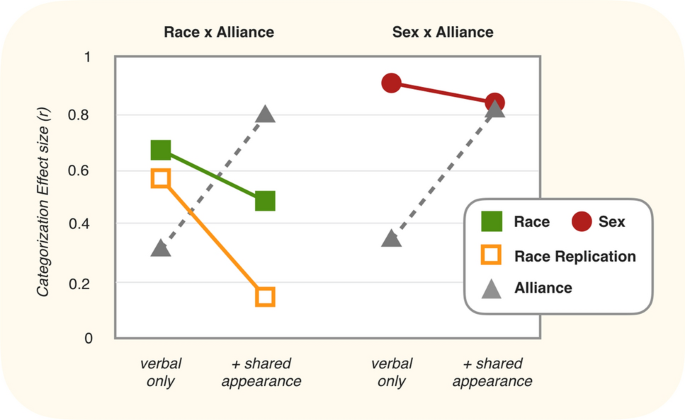

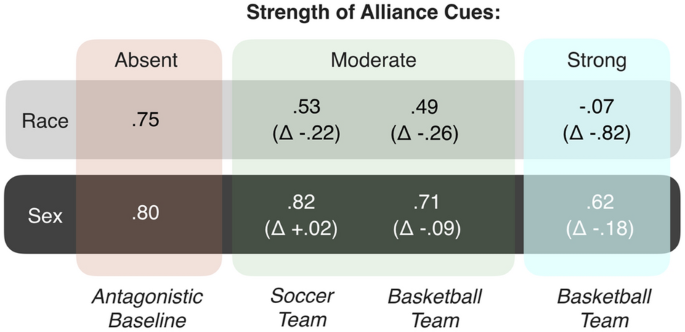

The results of four between-subjects conditions featuring race, and another four between-subjects conditions featuring sex, are presented in Fig. 2 . (For ease of comparison with past work, differences in means are reported using t-tests and related effect sizes; see SOM for full reporting, including means. Bayesian estimates of the differences in means 29 were also conducted and are reported in Fig. 4 and fully in the SOM . In all cases, both kinds of analysis lead to the same conclusions).

The left-most condition, antagonistic baseline , provided the critical baseline measurement of race and sex absent any alliance information. In this condition there was very strong categorization by both race ( r = 0.75) and sex ( r = 0.80), and no appreciable categorization by shirt color. (Shirt color in this baseline condition signified nothing, and was included so that shirt color differences would not be confounded with alliance information across conditions. In fact, for thoroughness—and to unconfound the effect of adding alliance information from the effect of adding antagonism to the study stimuli—two baseline conditions were: One in which targets spoke about positive-to-neutral events ( positive baseline ), and a second in which they spoke about antagonistic events ( antagonistic baseline ). For simplicity, only the antagonistic baseline is presented here, as it is the minimal pair with all three alliance conditions. Notably, there was no appreciable change in categorization by either race (∆ r = 0.04) or sex (∆ r = 0.02) across these two different baselines, although categorization by race did increase descriptively when antagonism was added ( positive r = 0.69, antagonistic r = 0.75), in contrast to sex ( positive r = 0.84, antagonistic r = 0.80; see SOM for full results)).

The crucial question was what would happen when race and sex are crossed with team membership—the experimental manipulation that should (1) engage the mind’s alliance-tracking leading to categorization by team and (2) that should differentially reduce categorization by race compared to sex. Results are presented in the three conditions to the right of the baselines in Fig. 2 (two featuring moderate strength alliance cues, and one strong alliance cues; see Box 2 for explanation).

Categorization effect sizes by both race and sex when crossed with alliance membership (in different sporting contexts), using standard t-tests and reported as r ’s. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Manipulation of alliance strength.

As can be seen, there was substantial categorization by team membership ( shirt/alliance ) in all three conditions. Importantly, this categorization cannot simply be attributed to the visual salience of the shirt colors—as the exact same visual stimuli were present in the baseline conditions, but elicited no categorization. Thus, participants were keeping track of and categorizing each target by their respective team membership—the first prediction of the alliance hypothesis.

The second and most important prediction of the alliance hypothesis is the differential reduction in race. As can be seen, compared to the baseline condition, categorization by race was reduced more than was sex, and this was true across all three alliance conditions. To fully unpack this result it is helpful to understand what each of the three alliance conditions were.

In all three, either race or sex was crossed with verbally and visually-marked team membership. Two of the three conditions featured moderately-strong alliance cues in the stimuli (in which the visual cues of team membership were removed during the recall task), whereas the third and last condition featured strong alliance cues in the stimuli (in which the visual cues of team membership were retained during the recall task). This variation in the strength of alliance cues provided both a within-study replication and a more continuous measurement of the effect of alliance cues on race and sex (see Box 2 and SOM ). Roughly speaking, the true effect of the alliance manipulation can be understood as lying somewhere between the moderate and strong conditions. Finally, one additional condition featuring soccer (European football) was also included to ensure that there were no idiosyncratic effects of a basketball sporting context (which was all that was used in Kurzban et al.).

As depicted in Fig. 2 , participants in the moderate alliance strength soccer condition categorized by race ( r = 0.53), but at a substantially-reduced level compared to baseline (∆ r = 0.38). The moderate basketball condition produced a nearly-identical result ( r = 0.49, ∆ r = 0.39). Finally, participants in the strong alliance strength condition (featuring basketball teams) did not even categorize by race at all ( r = -0.07, ∆ r = 0.54).

The results for sex were markedly weaker or non-existent. Participants in the moderate alliance strength soccer condition in fact categorized by sex even slightly more than compared to baseline ( r = 0.82, ∆ r = 0.38). In the moderate basketball condition participants again strongly categorized by sex ( r = 0.71). However, this time the level of categorization was slightly, but detectably, lower than that found in the baseline condition (∆ r = 0.27). Finally, participants in the strong alliance strength condition (featuring basketball teams) continued to categorize by sex at high levels ( r = 0.62). This level of categorization did reflect a lowering of categorization compared to baseline condition (∆ r = 0.41), but not compared to the moderate basketball condition (∆ r = 0.18). Thus, both basketball conditions (that this, both the moderate and strong conditions) did reduce categorization by sex to some degree; the reduction being somewhat lower in the strong condition. Finally, substantial categorization by team was found—replicating the effects found in the race conditions.

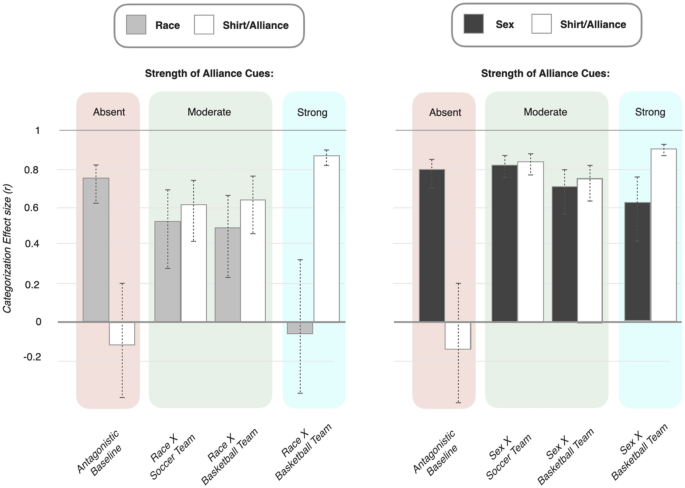

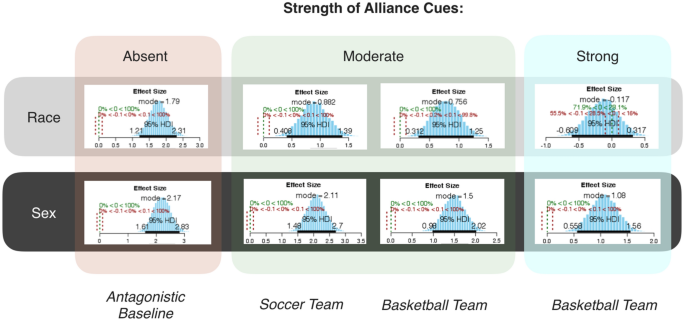

A summary of the changes in effect sizes across the different conditions for race and sex is depicted in Fig. 3 . As can be seen in Fig. 3 , a decrease in categorization by sex (i) did not occur at all in the moderate soccer condition, (ii) was 1/3rd the magnitude of the decrease in categorization by race (Δ r’s = 0.09 vs. 0.26, respectively) in the moderate basketball condition, and (iii) was 1/5th the magnitude (Δ r’s = 0.18 vs. 0.82, respectively) in the strong basketball condition. Figure 4 shows the same results for a Bayesian estimate of categorization effect sizes. As can be seen, the same overall pattern of results is found (see SOM for full report).

Categorization effect sizes ( r ) for race and sex across the baseline and alliance conditions, with changes in categorization (Δ) denoting the difference in magnitude compared to baseline.

Posterior distributions of categorization effect sizes, using Bayesian estimates of differences in means.

In sum, these results unambiguously support the predictions of the alliance hypothesis. Namely, that (1) categorization by a now-relevant alliance membership (team membership) will occur, and (2) racial categorization will be differentially lowered when it is shown to be no longer predictive of this alliance membership. Both effects replicated across each of the three team/alliance conditions.

Why people categorize others by their race is a fundamentally-important scientific problem with far-reaching sociological implications. The studies reported here provide the first adequate test of the alliance hypothesis of race—the hypothesis that racial categorization is a modifiable byproduct of alliance tracking—in the context of conflict. Given the long-standing evolutionary history of multi-agent conflict in our own and closely-related species 30 any hypothesis appealing to an evolved psychology of alliances must survive a test of its predictions under conditions of intergroup conflict. Here, we find that the alliance hypothesis of race in fact meets that standard.

The implications of this finding are far-reaching. First, it provides direct, experimental evidence for a particular causal account of where racial categorization comes from. Namely, that people categorize other people by their race (at least in part) because of exposure to social ecologies in which certain physical features correlate with or track patterns of segregation and discrimination. That is, if one happens to experience that particular physical features correlate with who tends to interact with whom, live with whom, and so on, then these patterns will get picked up by the minds’ alliance-tracking. It is then the operation of this alliance-tracking mental machinery (likely in concert with other mechanisms) that eventually delivers the impression that there are categories of people based on physical features.

Second, and more fundamentally, this finding suggests that racial perception and categorization is in a deep and fundamental way not about attention to physical features per se, but rather is really about predicting social relationships. In other words, out of all the ways in which people may look different from one another, only a subset of these differences become imbued with social relationship relevance over the course of one’s lifetime, and it is those differences that become the basis of automatic categorization. That is, race is a dimension of social categorization because of its social reality—not because of its biological reality or visual salience 24 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 . While this idea has historical support—in that the physical features considered “racial categories” have changed over historical time, as one would expect if it were a social construct 31 , 32 —it can also be directly tested within the mind. The social construction of race in the world, in other words, leaves its mark on the information-processing within the mind. Here, we find evidence for the social reality, but otherwise arbitrary nature, of racial categories.

The current studies are also notable because they provide an adequate test of a hypothesis presented nearly 20 years ago. The paper presenting this hypothesis—Kurzban et al. 6 —is incorrectly but more-or-less universally-cited as providing evidence in support of that hypothesis. Here, we have shown why this is not the case. The good news is that based on the current findings we can see that Kurzban et al. were ultimately correct about their hypothesis. The bad news is that it took nearly 20 years for anyone to notice that the design of that paper did not provide adequate evidence in support of it.

It is a testament to the alliance hypothesis and the evolutionary framework that generated it that its predictions have stood up to experimental scrutiny nearly two decades later. But it is no compliment to the wide variety of psychological and behavioral sciences that had consumed the original Kurzban et al. finding that the inadequacy of that experimental design was missed for so long in such a high-profile paper. This should be cause for concern.

Indeed, while statistical analysis and its reporting have received considerable attention lately in light of the replication crisis—with a corresponding focus on the question of “does the experimental effect replicate?” 22 —far less attention has been paid to the more important issue of experimental design and its applicability to the theory that it was set up to test in the first place (see Fig. 5 ).

In the process from going from theory to inference using empirical methods, considerable attention has been paid to issues surrounding statistical analysis (step three), but considerably less to the adequacy of experimental design (step two).

The issue of experimental design is critical for understanding exactly why we cannot—and should not have—made any strong inferences based on the results of Kurzban et al. Leaving aside the issue of the biased error correction method, and thus ignoring our uncertainty about the accuracy of the numbers reported (see Introduction ), a reasonable reader may wonder why we cannot use the fact that race was reduced in Kurzban et al. as a demonstration of the validity of the alliance hypothesis of race. The problem is that we cannot know why race was reduced in Kurzban et al. because in that study there was a failure to experimentally-isolate the effect of crossing race with alliance membership from the effect of adding shirt color to the stimuli. Here, in contrast, because the non-alliance baseline condition also featured differences in shirt color, we can be certain that our effects were only due to the alliance membership manipulation, and not caused by shirt color differences.

Moreover, because we did also manipulate the presence or absence of shirt color differences within the alliance conditions (at recall) here, we can directly assess if shirt color differences do have an additional effect on racial categorization—when (and only when) they mark alliance membership. We find here that they do. Thus, based on our results, we can speculate that perhaps the reduction in race found in Kurzban et al. was after all due to alliance cues in the stimuli—although we can never be certain of this because those results are contaminated by (1) the biased error correction method and (2) a matching strategy that can lead to an across-the board reduction in both race and sex as a result of an experimental artifact (see Box 2 and SOM ), both of which may have fully accounted for their results. Thus, the best we can say for the Kurzban et al. study is that it was the source of an important and subsequently supported hypothesis, but did not provide adequate evidence in support of it.

Of course, it would be remarkable if the first attempt to empirically-validate a new hypothesis turned out, in the fullness of time, to be the soundest evidence in support of it. The current situation just happens to be a particularly extreme case. Notwithstanding that adequate and necessary tests of the hypothesis have taken some time to establish, with the inclusion of the results found here and elsewhere, the alliance hypothesis is beginning to collect a substantial evidentiary basis. Indeed, converging lines of evidence, from multiple methodologies, are consistent with the idea that the mind did not evolve to categorize others by their race 12 , 35 , 36 ("race” being an arbitrary and socially-contingent construct in any case). Rather, race appears to be an instance of a broader, more-general evolved entry in the human mind—one (at least in part) concerned with tracking patterns of alliance and affiliation 14 , 17 , 18 , 20 , 33 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 . In other words, although a seemingly self-evident feature of the world, race is in fact a highly-abstract social construction, built by our evolved cognition when operating within specific kinds of social environments. In particular, if and when certain physical features become imbued with alliance-relevant information (i.e., they predict who interacts with whom, who lives with whom, etc.), then these will come to be treated as important social cues by the mind, and will be perceived as psychologically-salient. For this reason, when the hypothesized inputs to the mind’s alliance-tracking systems are satisfied in the form of clearer information about who is allied with whom, the psychological relevance of race dissipates. Such findings—capped off by the present studies—suggest that we might next aspire to do more than simply erase race, but rather more deeply understand it.

All alliance conditions featured an antagonistic encounter between the members of two sports teams, in which either race or sex (varied between-subjects) was crossed with visually and verbally-marked team membership. That is, on each team there were an equal number of Black and White or male and female players. Categorization by both team and the cross-cutting dimension (either race or sex) was measured (how will be explained below).

Non-alliance baseline conditions provided the critical measure of categorization by race and by sex absent any cross-cutting team membership. These baseline conditions were as closely matched to the alliance/team conditions as possible, including using the exact same photo stimuli (i.e., the same faces and shirt color differences) and closely-matched statements. However, all content that would suggest to participants that these were two different sports teams was removed. Thus, participants simply observed individuals making random statements stripped of any alliance cues (see SOM for statements).

There were two of these baseline conditions. One featured positively-valanced statements. The other featured antagonistic statements. Including both was necessary because in the alliance conditions, antagonism and team membership are both present. That is, team members are discussing conflict and fighting. Therefore, if one were to only compare the team/alliance conditions to a neutral baseline condition, one could not establish if any change in categorization by either race or sex was due to either the team/alliance membership in the statements, or to the antagonism in the statements. There are good reasons to be concerned about this. For example, it may be that antagonism prompts attention to race, but drops attention to sex. A neutral to positively-valanced baseline condition was therefore included to first establish baseline levels of categorization by race and sex absent both antagonism and team membership. A second, antagonistic baseline was then also included to compare to this positive baseline. This antagonistic baseline then served as a valanced-matched comparison to the alliance/team conditions.

Three different versions of the alliance/team conditions were run. In all three, race or sex was crossed with team membership. Two of the three conditions differed in the sport being presented, but were otherwise identical. One of these featured basketball teams, following Kurzban et al. The other featured soccer/European football teams. Varying the sporting context provided a within-study replication and ensured that there was nothing idiosyncratic about the basketball team context.

The third and final alliance/team condition was designed to directly measure the potential impact of an experimental artifact that would have allowed participants to simply match verbal and visual cues of team membership during the recall task (see Box 2 and SOM ). Past research suggests that this artifact will likely over-inflate the true effect of categorization by team, and may produce a small, domain-general decrease in categorization by the crossed category 17 , 41 . Here, rather than avoiding the artifact, it was intentionally produced in this one condition. Thus, rather than speculating about what might happen if this artifact is present, we can directly assess what happens experimentally (for details of how this artifact was implemented in this third condition, and prevented in the other two alliance/team conditions, see Box 2 and SOM ).

All five conditions—the two baselines and three alliance conditions—were presented within either in a context in which targets differed in race or in sex. Thus, ten between-subjects conditions were run in total.

All conditions were run using the memory confusion paradigm 17 , 26 , 42 , 43 , 44 . This paradigm measures categorization by capturing patterns of errors in memory—specifically, speaker-attribution errors 28 . In the initial phase of the paradigm, a sequence of photos of individual people is presented. Each photo is accompanied by a statement (appearing in text in these studies). Participants are instructed to form impressions of the speakers. After the presentation of photos and statements (here, eight speakers making three statements each, for a total of 24 statements), a short, unrelated distractor task appears. This is used to avoid recency and rehearsal effects. In the final phase, participants are shown an array all of the speakers, and are asked to assign each statement that they had seen previously to the correct speaker (for full details, see Box 1 and SOM ).

Errors rates in this attribution task, which are typically quite high, diagnose categorization: To the degree a participant categorized speakers by one or more shared-dimensions (such as team membership or race or sex), they will be more likely to make within-category errors than between-category errors (for details of the error rate calculation, including a new and improved correction for base-rate probabilities 27 , 28 ). Thus, for each participant, three data points are calculated: (1) total errors, (2) within-category errors, and (3) between-category errors. The effect size of the within- versus between-category error difference quantifies categorization.

Participants and procedure

Participants were 396 University of California at Santa Barbara undergraduate students (mean age 19.01 years, SD = 1.39; 284 F, 110 M, 2 unspecified). These participated in-person in a computer lab for course credit. A minimum sample size of 33 participants per condition was determined ahead of time based on past studies of this type (typical effect sizes in social categorization research of this type are now well-established based on larger sample-size studies 17 ), with the stipulation that additional participants would be collected if available from the subject pool. No data were analyzed until the termination of running. Final participant count per condition ranged between 37–41 participants per condition. Research assistants blind to the details of the conditions were instructed to note if any participants egregiously rushed through the task or were extremely distracted (if they were on their phone, for example). Four out of 400 total participants were flagged according to these criteria, and the data from these four were never analyzed.

After completing the memory confusion task, participants filled out a short demographic sheet, indicating their age and sex. Demographics of two participants could not be determined. No pilot tested was conducted. Data stripped of participant-identification are freely-available as Supplementary Online Materials, as are the instructions and statement stimuli. The study protocol was approved by the University of California at Santa Barbara IRB, and as such the running of the study was performed in accordance with all relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Data availability

Data stripped of participant-identification are freely-available as Supplementary Online Materials published alongside this article.

Katz, D. & Braly, K. Racial stereotypes of one hundred college students. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 28 , 280–290 (1933).

Article Google Scholar

Allport, G. W. The Nature of Prejudice (Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, 1954).

Google Scholar

Lippmann, W. Public Opinion (Harcourt, Brace & Co, New York, 1922).

Hamilton, D. L. & Gifford, R. K. Illusory correlation in interpersonal perception: A cognitive basis of stereotypic judgments. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 12 , 392–407 (1976).

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D. & Wetherell, M. S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory (Blackwell, Oxford, 1987).

Kurzban, R., Tooby, J. & Cosmides, L. Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 , 15387–15392 (2001).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lepore, L. & Brown, R. Exploring automatic stereotype activation: A challenge to the inevitability of stereotypes. In Social Identity and Social Cognition (eds Abrams, D. & Hogg, M. A.) 141–163 (Blackwell, Malden, 1999).

Yzerbyt, V. & Corneille, O. Cognitive process: Reality constraints and integrity concerns in social perception. In On the Nature of Prejudice (eds Dovidio, J. F. et al. ) 175–191 (Blackwell, Malden, 2005).

Cosmides, L., Tooby, J. & Kurzban, R. Perceptions of race. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7 , 173–179 (2003).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pietraszewski, D. What is group psychology? Adaptations for mapping shared intentional stances. In Navigating the social world: What infants, children, and other species can teach us (eds Banaji, M. & Gelman, S.) 253–257 (Oxford University Press, New York, 2013).

Chapter Google Scholar

Neuberg, S. L. & Sng, O. A life history theory of social perception: Stereotyping at the intersections of age, sex, ecology (and race). Soc. Cogn. 31 , 696–711 (2013).

Williams, K. E., Sng, O. & Neuberg, S. L. Ecology-driven stereotypes override race stereotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113 (2), 310–315 (2016).

Boyer, P., Firat, R. & van Leeuwen, F. Safety, threat, and stress in intergroup relations: A coalitional index mode. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10 , 434–450 (2015).

Cikara, M., Van Bavel, J. J., Ingbretsen, Z. A. & Lau, T. Decoding “us” and “them”: Neural representations of generalized group concepts. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 5 , 621–631 (2017).

Kunst, J. R., Thomsen, L. & Dovidio, J. F. Divided loyalties: Perceptions of disloyalty underpin bias toward dually-identified minority-group members. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 17 (4), 807–838 (2019).

Lewis, D. M. G., Al-Shawaf, L., Conroy-Beam, D., Asao, K. & Buss, D. M. Evolutionary psychology: A how-to guide. Am. Psychol. 72 (4), 353–373 (2017).

Pietraszewski, D., Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. The content of our cooperation, not the color of our skin: An alliance detection system regulates categorization by coalition and race, but not sex. PLoS ONE 9 (2), e88534. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088534 (2014).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pietraszewski, D., Curry, O., Peterson, M. B., Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. Constituents of political cognition: Race, party politics, and the alliance detection system. Cognition 140 , 24–39 (2015).

Simon, J. C. & Gutsell, J. N. Effects of minimal grouping on implicit prejudice, infrahumanization, and neural processing despite orthogonal social categorizations. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 23 , 323–343 (2019).

Van Bavel, J. J., Packer, D. J. & Cunningham, W. A. The neural substrates of in-group bias: A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Psychol. Sci. 19 , 1130–1138 (2008).

Palma, T. A., Garcia-Marques, L., Marques, P., Hagá, S. & Payne, B. K. Learning what to inhibit: The influence of repeated testing on the encoding of gender and age information. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 116 , 899–918 (2019).

Voorspoels, W., Bartlema, A. & Vanpaemel, W. Can race really be erased? A pre-registered replication study. Frontiers https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01035 (2014).

Frable, D. E. S. & Bem, S. L. If you are gender schematic, all members of the opposite sex look alike. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 49 , 459–468 (1985).

Stangor, C., Lynch, L., Duan, C. & Glass, B. Categorization of individuals on the basis of multiple social features. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 62 , 207–218 (1992).

Susskind, J. E. Preadolescents’ categorization of gender and ethnicity at the subgroup level in memory. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 25 , 213–225 (2007).

Taylor, S. E., Fiske, S. T., Etcoff, N. L. & Ruderman, A. J. Categorical and contextual bases of person memory and stereotyping. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 36 , 778–793 (1978).

Bor, A. Correcting for base rates in multidimensional “Who said what? experiments. Evol. Hum. Behav. 39 , 473–478 (2018).

Pietraszewski, D. A reanalysis of crossed-dimension “Who Said What?” paradigm studies, using a better error base-rate correction. Evol. Hum. Behav. 39 , 479–489 (2018).

Kruschke, J. K. Bayesian estimation supersedes the t test. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 142 , 573–603 (2013).

Wrangham, R. W. & Glowacki, L. Intergroup aggression in chimpanzees and war in nomadic hunter-gatherers. Hum. Nat. 23 , 5–29 (2012).

Graves, J. L. The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium (Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 2001).

Hirschfeld, L. A. Race in the Making: Cognition, Culture, and the Child’s Construction of Human Kinds (MIT Press, Cambridge, 1996).

Sidanius, J. & Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression (Cambridge University Press, New York, 1999).

Book Google Scholar

Tishkoff, S. A. & Kidd, K. K. Implications of biogeography of human populations for ‘race’ and medicine. Nat. Genet. 36 , 521–527 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bernstein, M. J., Young, S. G. & Hungenberg, K. The cross-category effect: Mere social categorization is sufficient to elicit an own-group bias in face recognition. Psychol. Sci. 18 , 342–345 (2007).

Golkar, A. & Olsson, A. The interplay of social group biases in social threat learning. Sci. Rep. 7 , 7685 (2017).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Craig, M. A., Rucker, J. M. & Richeson, J. A. The pitfalls and promise of increasing racial diversity: Threat, contact, and race relations in the 21st century. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 27 , 188–193 (2018).

Dunham, Y. Mere membership. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22 , 780–793 (2018).

Enos, R. D. & Celaya, C. The effect of segregation on intergroup relations. J. Exp. Polit. Sci. 5 , 26–38 (2018).

Gelman, S. A. & Roberts, S. O. How language shapes the cultural inheritance of categories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114 , 7900–7907 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pietraszewski, D. & Schwartz, A. Evidence that accent is a dedicated dimension of social categorization, not a byproduct of coalitional categorization. Evol. Hum. Behav. 35 , 51–57 (2014).

Lieberman, D., Oum, R. & Kurzban, R. The family of fundamental social categories includes kinship: Evidence from the memory confusion paradigm. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38 , 998–1012 (2008).

Petersen, M. B. Healthy out-group members are represented psychologically as infected in-group members. Psychol. Sci. 28 , 1857–1863 (2017).

van Leeuwen, F., Park, J. H. & Penton-Voak, I. S. Another fundamental social category? Spontaneous categorization of people who uphold or violate moral norms. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48 , 1385–1388 (2012).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Leda Cosmides for providing access to the UCSB participant pool, and Jordan Lyle for assistance in running the studies.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Adaptive Rationality, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Lentzeallee 94, 14195, Berlin, Germany

David Pietraszewski

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

D.P. designed the studies, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Pietraszewski .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information 1., supplementary information 2., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pietraszewski, D. The correct way to test the hypothesis that racial categorization is a byproduct of an evolved alliance-tracking capacity. Sci Rep 11 , 3404 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82975-x

Download citation

Received : 13 November 2020

Accepted : 27 January 2021

Published : 09 February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82975-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

11.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe how major sociological perspectives view race and ethnicity

- Identify examples of culture of prejudice

Theoretical Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity

We can examine race and ethnicity through three major sociological perspectives: functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. As you read through these theories, ask yourself which one makes the most sense and why.

Functionalism

Functionalism emphasizes that all the elements of society have functions that promote solidarity and maintain order and stability in society. Hence, we can observe people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds interacting harmoniously in a state of social balance. Problems arise when one or more racial or ethnic groups experience inequalities and discriminations. This creates tension and conflict resulting in temporary dysfunction of the social system. For example, the killing of a Black man George Floyd by a White police officer in 2020 stirred up protests demanding racial justice and changes in policing in the United States. To restore the society’s pre-disturbed state or to seek a new equilibrium, the police department and various parts of the system require changes and compensatory adjustments.

Another way to apply the functionalist perspective to race and ethnicity is to discuss the way racism can contribute positively to the functioning of society by strengthening bonds between in-group members through the ostracism of out-group members. Consider how a community might increase solidarity by refusing to allow outsiders access. On the other hand, Rose (1951) suggested that dysfunctions associated with racism include the failure to take advantage of talent in the subjugated group, and that society must divert from other purposes the time and effort needed to maintain artificially constructed racial boundaries. Consider how much money, time, and effort went toward maintaining separate and unequal educational systems prior to the civil rights movement.

In the view of functionalism, racial and ethnic inequalities must have served an important function in order to exist as long as they have. This concept, sometimes, can be problematic. How can racism and discrimination contribute positively to society? Nash (1964) focused his argument on the way racism is functional for the dominant group, for example, suggesting that racism morally justifies a racially unequal society. Consider the way slave owners justified slavery in the antebellum South, by suggesting Black people were fundamentally inferior to White and preferred slavery to freedom.

Interactionism

For symbolic interactionists, race and ethnicity provide strong symbols as sources of identity. In fact, some interactionists propose that the symbols of race, not race itself, are what lead to racism. Famed Interactionist Herbert Blumer (1958) suggested that racial prejudice is formed through interactions between members of the dominant group: Without these interactions, individuals in the dominant group would not hold racist views. These interactions contribute to an abstract picture of the subordinate group that allows the dominant group to support its view of the subordinate group, and thus maintains the status quo. An example of this might be an individual whose beliefs about a particular group are based on images conveyed in popular media, and those are unquestionably believed because the individual has never personally met a member of that group.

Another way to apply the interactionist perspective is to look at how people define their races and the race of others. Some people who claim a White identity have a greater amount of skin pigmentation than some people who claim a Black identity; how did they come to define themselves as Black or White?

Conflict Theory

Conflict theories are often applied to inequalities of gender, social class, education, race, and ethnicity. A conflict theory perspective of U.S. history would examine the numerous past and current struggles between the White ruling class and racial and ethnic minorities, noting specific conflicts that have arisen when the dominant group perceived a threat from the minority group. In the late nineteenth century, the rising power of Black Americans after the Civil War resulted in draconian Jim Crow laws that severely limited Black political and social power. For example, Vivien Thomas (1910–1985), the Black surgical technician who helped develop the groundbreaking surgical technique that saves the lives of “blue babies” was classified as a janitor for many years, and paid as such, despite the fact that he was conducting complicated surgical experiments. The years since the Civil War have showed a pattern of attempted disenfranchisement, with gerrymandering and voter suppression efforts aimed at predominantly minority neighborhoods.

Intersection Theory

Feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990) further developed intersection theory , originally articulated in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw, which suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other attributes (Figure 11.4). When we examine race and how it can bring us both advantages and disadvantages, it is important to acknowledge that the way we experience race is shaped, for example, by our gender and class. Multiple layers of disadvantage intersect to create the way we experience race. For example, if we want to understand prejudice, we must understand that the prejudice focused on a White woman because of her gender is very different from the layered prejudice focused on an Asian woman in poverty, who is affected by stereotypes related to being poor, being a woman, and her ethnic status.

Culture of Prejudice

Culture of prejudice refers to the theory that prejudice is embedded in our culture. We grow up surrounded by images of stereotypes and casual expressions of racism and prejudice. Consider the casually racist imagery on grocery store shelves or the stereotypes that fill popular movies and advertisements. It is easy to see how someone living in the Northeastern United States, who may know no Mexican Americans personally, might gain a stereotyped impression from such sources as Speedy Gonzalez or Taco Bell’s talking Chihuahua. Because we are all exposed to these images and thoughts, it is impossible to know to what extent they have influenced our thought processes.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/11-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-race-and-ethnicity

© Aug 5, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Advertisement

Racial Threat and Crime Control: Integrating Theory on Race and Extending its Application

- Published: 18 January 2020

- Volume 29 , pages 253–271, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Justin Smith ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6722-3095 1

1657 Accesses

11 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The racial threat perspective has been applied increasingly to the study of crime control over the past several decades and demonstrates appealing and nuanced arguments for understanding racial bias and disparity. As recent tests of racial threat hypotheses have illustrated, however, the empirical results are mixed. This article seeks to refine the racial threat perspective and addresses methodological limitations. It also explores the application of the racial threat framework to contemporary social landscapes. Discussion concentrates on three distinct issues that seek to develop theory, methodology and epistemology in racial threat research: (1) theoretical integration of the nuances of race relations; (2) relativity of criminal justice systems; and (3) historical and structural racism in crime control.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A Sociobehavioral Model of Racism against the Black Community and Avenues for Anti-Racism Research

Seeing beyond Black and White to understand anti-Latinx crimes of bias

The Psychology of Race and Policing

What I refer to as the “racial threat perspective” appears under different labels throughout the literature. Because this article focuses on race, it uses “racial threat” throughout, recognizing that “racial threat” is connected to and falls under the larger concept of “social threat.”

The focus here is mostly on courts, but it is also applicable to other parts of the criminal justice system.

For several of the most comprehensive analyses of mass incarceration, see Garland ( 2012 ), Gottschalk ( 2006 ), Pfaff ( 2017 ), Western ( 2006 ).

While some racial threat research argues that a racial threat will increase social control overall, rather than just racially disparate control, this article focuses upon racially unequal control (Liska 1992 ).

It is reasonable to suspect that there are several other statistical models that have been run by analysts, which have found racial threat hypotheses to have nonsignificant relationships. If so, the extent of mixed results has been estimated inaccurately and raised additional theoretical questions.

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness . New York: The New Press.

Google Scholar

Baumer, E. P. (2013). Reassessing and redirecting research on race and sentencing. Justice Quarterly, 30 (2), 231–261.

Baumer, E. P., Messner, S. F., & Rosenfeld, R. (2003). Explaining spatial variation in support for capital punishment: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 108 (4), 844–875.

Benz, T. A. (2014). At the intersection of urban sociology and criminology: Fear of crime and the postindustrial city. Sociology Compass, 8 (1), 10–19.

Blalock, H. M. (1967). Toward a theory of minority-group relations . New York: Wiley.

Blauner, R. (1972). Racial oppression in America . New York: Harper & Row.

Blumer, H. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Sociological Review, 1 (1), 3–7.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review , 62 (3), 465–480.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2014). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States (4th ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2019). Feeling race: Theorizing the racial economy of emotions. American Sociological Review, 84 (1), 1–25.

Brotherton, D., & Kretsedemas, P. (2017). Immigration policy in the age of punishment: Detention, deportation, and border control . New York: Columbia University Press.

Bushway, S. D., & Forst, B. (2013). Studying discretion in the processes that generate criminal justice sanctions. Justice Quarterly, 30 (2), 199–222.

Bushway, S., Johnson, B., & Slocum, L. (2007). Is the magic still there? The use of the heckman two-step correction for selection bias in criminology. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 23 (2), 151–178.

Charles, C. Z. (2003). The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annual Review of Sociology, 29 (1), 167–207.

Clair, M., & Winter, A. (2016). How judges think about racial disparities: Situational decision-making in the criminal justice system. Criminology, 54 (2), 332–359.

Clay, P. (1979). Neighborhood renewal: Middle-class resettlement and incumbent upgrading in American neighborhoods . Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Clinton, G., Collins, B., & Worrell, B. (1975). Chocolate city. In chocolate city. Parliament. Casablanca Records.

Croll, P. R. (2007). Modeling determinants of white racial identity: Results from a new national survey. Social Forces, 86 (2), 613–642.

Dozier, D. (2019). Contested Development: Homeless property, police reform, and resistance in Skid Row, LA. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43 (1), 179–194.

Eisenstein, J., Flemming, R., & Nardulli, P. (1988). The contours of justice: Communities and their courts . Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Engen, R. L. (2009). Assessing determinate and presumptive sentencing: Making research relevant. Criminology and Public Policy, 8 (2), 323–336.

Feldmeyer, B., Warren, P. Y., Siennick, S. E., & Neptune, M. (2015). Racial, ethnic, and immigrant threat: Is there a new criminal threat on state sentencing? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 52 (1), 62–92.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class . New York: Basic Books.

Forman, J., Jr. (2017). Locking up our own: Crime and punishment in Black America . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Fortner, M. J. (2015). Black silent majority . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Freeman, L. (2005). There goes the hood: Views of gentrification from the ground up . Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Garland, D. (2012). The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Glover, K. S. (2009). Racial profiling: Research, racism, and resistance . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Gottschalk, M. (2006). The prison and the gallows: The politics of mass incarceration in America . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.