Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 15 March 2024

The process and mechanisms of personality change

- Joshua J. Jackson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9490-8890 1 &

- Amanda J. Wright ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8873-9405 2

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 3 , pages 305–318 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1696 Accesses

4 Citations

208 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Personality

Although personality is relatively stable across the lifespan, there is also ample evidence that it is malleable. This potential for change is important because many individuals want to change aspects of their personality and because personality influences important life outcomes. In this Review, we examine the mechanisms responsible for intentional and naturally occurring changes in personality. We discuss four mechanisms — preconditions, triggers, reinforcers and integrators — that are theorized to produce effective change, as well as the forces that promote stability, thereby thwarting enduring changes. Although these mechanisms are common across theories of personality development, the empirical evidence is mixed and inconclusive. Personality change is most likely to occur gradually over long timescales but abrupt, transformative changes are possible when change is deliberately attempted or as a result of biologically mediated mechanisms. When change does occur, it is often modest in scale. Ultimately, it is difficult to cultivate a completely different personality, but small changes are possible.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

55,14 € per year

only 4,60 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Disentangling the personality pathways to well-being

Individual and generational value change in an adult population, a 12-year longitudinal panel study

Personality beyond taxonomy

Hudson, N. W. & Roberts, B. W. Goals to change personality traits: concurrent links between personality traits, daily behavior, and goals to change oneself. J. Res. Personal. 53 , 68–83 (2014).

Google Scholar

Beck, E. D. & Jackson, J. J. A mega-analysis of personality prediction: robustness and boundary conditions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 122 , 523–553 (2022).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Soto, C. J. How replicable are links between personality traits and consequential life outcomes? The life outcomes of personality replication project. Psychol. Sci. 30 , 711–727 (2019).

PubMed Google Scholar

Bleidorn, W. et al. Personality stability and change: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 148 , 588–619 (2022).

Wright, A. J. & Jackson, J. J. Are some people more consistent? Examining the stability and underlying processes of personality profile consistency. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 124 , 1314–1337 (2023).

Bleidorn, W. et al. The policy relevance of personality traits. Am. Psychol. 74 , 1056–1067 (2019). This paper highlights the importance of intervening on personality traits.

Bleidorn, W., Hopwood, C. J. & Lucas, R. E. Life events and personality trait change. J. Pers. 86 , 83–96 (2018).

Bühler, J. L. et al. Life events and personality change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Personal. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070231190219 (2023).

Allemand, M. & Flückiger, C. Personality change through digital-coaching interventions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 31 , 41–48 (2022). This paper provides an overview of a successful digital coaching intervention.

Allemand, M. & Flückiger, C. Changing personality traits: some considerations from psychotherapy process–outcome research for intervention efforts on intentional personality change. J. Psychother. Integr. 27 , 476–494 (2017). This broad theoretical overview on how to intervene to change personality borrows from ideas developed in psychotherapy.

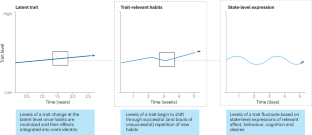

Geukes, K., Zalk, M. & Back, M. D. Understanding personality development: an integrative state process model. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 42 , 43–51 (2018). This paper presents an innovative theoretical model on how personality develops.

Hennecke, M., Bleidorn, W., Denissen, J. J. A. & Wood, D. A three-part framework for self-regulated personality development across adulthood. Eur. J. Personal. 28 , 289–299 (2014). This article presents a theoretical model of how personality develops through the lens of self-regulation.

Wrzus, C. & Roberts, B. W. Processes of personality development in adulthood: the TESSERA framework. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 21 , 253–277 (2017). This article provides a detailed process view of the many potential intervening processes that result in personality change.

Baumert, A. et al. Integrating personality structure, personality process, and personality development. Eur. J. Personal. 31 , 503–528 (2017).

Roberts, B. W. & Jackson, J. J. Sociogenomic personality psychology. J. Pers. 76 , 1523–1544 (2008).

Roberts, B. W. A revised sociogenomic model of personality traits. J. Pers. 86 , 23–35 (2018).

Magidson, J. F., Roberts, B. W., Collado-Rodriguez, A. & Lejuez, C. W. Theory-driven intervention for changing personality: expectancy value theory, behavioral activation, and conscientiousness. Dev. Psychol. 50 , 1442 (2014). This article presents a therapy-informed theoretical account of the personality change process.

Roberts, B. W. & Caspi, A. in Understanding Human Development (eds Staudinger, U. M. & Lindenberger, U.) 183–214 (Springer, 2003). This chapter reviews the types of process that result in change and consistency in passive longitudinal studies.

Roberts, B. W. & Nickel, L. B. in Handbook of Personality Theory and Research (eds John, O. & Robins, R. W.) 259–283 (Guilford, 2021).

Specht, J. et al. What drives adult personality development? A comparison of theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence. Eur. J. Personal. 28 , 216–230 (2014). This article provides an overview of the predominant theoretical models of personality development.

Scarr, S. & McCartney, K. How people make their own environments: a theory of genotype → environment effects. Child. Dev. 54 , 424–435 (1983).

Briley, D. A. & Tucker-Drob, E. M. Genetic and environmental continuity in personality development: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 140 , 1303–1331 (2014).

Roberts, B. W. & Yoon, H. J. Personality psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 73 , 489–516 (2022).

Wilt, J. & Revelle, W. Affect, behaviour, cognition and desire in the Big Five: an analysis of item content and structure. Eur. J. Personal. 29 , 478–497 (2015).

Stieger, M. et al. Becoming more conscientious or more open to experience? Effects of a two‐week smartphone‐based intervention for personality change. Eur. J. Personal. 34 , 345–366 (2020).

Rosenberg, E. L. Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2 , 247–270 (1998).

Roberts, B. W. & Pomerantz, E. M. On traits, situations, and their integration: a developmental perspective. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 8 , 402–416 (2004). This article presents one of the most successful personality interventions.

Hooker, K. & McAdams, D. P. Personality reconsidered: a new agenda for aging research. J. Gerontol. B 58 , 296–304 (2003).

Terracciano, A., Stephan, Y., Luchetti, M. & Sutin, A. R. Cognitive impairment, dementia, and personality stability among older adults. Assessment 25 , 336–347 (2018).

Caselli, R. J. et al. Personality changes during the transition from cognitive health to mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66 , 671–678 (2018).

Robins Wahlin, T.-B. & Byrne, G. J. Personality changes in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiat. 26 , 1019–1029 (2011).

Tang, T. Z. et al. Personality change during depression treatment: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 66 , 1322–1330 (2009).

Quilty, L. C., Meusel, L.-A. C. & Bagby, R. M. Neuroticism as a mediator of treatment response to SSRIs in major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 111 , 67–73 (2008).

Max, J. E. et al. Predictors of personality change due to traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents in the first six months after injury. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiat. 44 , 434–442 (2005).

Chapman, B. P., Hampson, S. & Clarkin, J. Personality-informed interventions for healthy aging: conclusions from a national institute on aging workgroup. Dev. Psychol. 50 , 1426–1441 (2014).

Wood, W. & Rünger, D. Psychology of habit. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67 , 289–314 (2016).

Weiss, B., Miller, J. D., Carter, N. T. & Keith Campbell, W. Examining changes in personality following shamanic ceremonial use of ayahuasca. Sci. Rep. 11 , 6653 (2021).

Owens, M. et al. Habitual behavior as a mediator between food-related behavioral activation and change in symptoms of depression in the MooDFOOD trial. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 9 , 649–665 (2021).

Martell, C. R., Addis, M. E. & Jacobson, N. S. Depression in Context: Strategies for Guided Action (W W Norton & Co, 2001).

Watkins, E. R. & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. A habit–goal framework of depressive rumination. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 123 , 24–34 (2014).

Lally, P. & Gardner, B. Promoting habit formation. Health Psychol. Rev. 7 , 137–158 (2013).

Denissen, J. J. A., van Aken, M. A. G., Penke, L. & Wood, D. Self‐regulation underlies temperament and personality: an integrative developmental framework. Child. Dev. Perspect. 7 , 255–260 (2013).

Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W. & Wardle, J. How are habits formed: modelling habit formation in the real world. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 40 , 998–1009 (2010).

Danner, U. N., Aarts, H. & de Vries, N. K. Habit vs. intention in the prediction of future behaviour: the role of frequency, context stability and mental accessibility of past behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 47 , 245–265 (2008).

Wood, W. & Neal, D. T. A new look at habits and the habit–goal interface. Psychol. Rev. 114 , 843–863 (2007).

Fleeson, W. Toward a structure- and process-integrated view of personality: traits as density distributions of states. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80 , 1011–1027 (2001).

Eid, M. & Diener, E. Global judgments of subjective well-being: situational variability and long-term stability. Soc. Indic. Res. 65 , 245–277 (2004).

Geukes, K., Nestler, S., Hutteman, R., Küfner, A. C. P. & Back, M. D. Trait personality and state variability: predicting individual differences in within- and cross-context fluctuations in affect, self-evaluations, and behavior in everyday life. J. Res. Personal. 69 , 124–138 (2017).

Reitz, A. K. Self‐esteem development and life events: a review and integrative process framework. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 16 , 12709 (2022).

Stieger, M. et al. Changing personality traits with the help of a digital personality change intervention. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118 , (2021).

Hampson, S. E. Personality processes: mechanisms by which personality traits ‘get outside the skin’. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63 , 315–339 (2012).

Specht, J., Egloff, B. & Schmukle, S. C. Examining mechanisms of personality maturation: the impact of life satisfaction on the development of the big five personality traits. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 4 , 181–189 (2013).

Hudson, N. W. Does successfully changing personality traits via intervention require that participants be autonomously motivated to change? J. Res. Personal. 95 , 104160 (2021).

Borghuis, J. et al. Longitudinal associations between trait neuroticism and negative daily experiences in adolescence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 118 , 348–363 (2020).

van Zalk, M. H. W., Nestler, S., Geukes, K., Hutteman, R. & Back, M. D. The codevelopment of extraversion and friendships: bonding and behavioral interaction mechanisms in friendship networks. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 118 , 1269–1290 (2020).

Quintus, M., Egloff, B. & Wrzus, C. Daily life processes predict long-term development in explicit and implicit representations of Big Five traits: testing predictions from the TESSERA (Triggering situations, Expectancies, States and State Expressions, and ReActions) framework. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 120 , 1049–1073 (2021).

Wrzus, C., Luong, G., Wagner, G. G. & Riediger, M. Longitudinal coupling of momentary stress reactivity and trait neuroticism: specificity of states, traits, and age period. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 121 , 691–706 (2021).

Hudson, N. W., Briley, D. A., Chopik, W. J. & Derringer, J. You have to follow through: attaining behavioral change goals predicts volitional personality change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 117 , 839–857 (2019).

Roberts, B. W. & Wood, D. in Handbook of Personality Development (eds Mroczek, D. K. & Little, T. D.) 11–39 (Pyschology Press, 2006).

Lehnart, J., Neyer, F. J. & Eccles, J. Long-term effects of social investment: the case of partnering in young adulthood. J. Pers. 78 , 639–670 (2010).

Helson, R., Kwan, V. S. Y., John, O. P. & Jones, C. The growing evidence for personality change in adulthood: findings from research with personality inventories. J. Res. Personal. 36 , 287–306 (2002).

Caspi, A. & Roberts, B. W. in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research 2nd edn (eds John, O. P. & Robins, R. W.) 300–326 (Guilford Press, 1999).

Sarbin, T. R. The dangerous individual: an outcome of social identity transformations. Br. J. Criminol. 7 , 285–295 (1967).

Roberts, B. W., Wood, D. & Smith, J. L. Evaluating five factor theory and social investment perspectives on personality trait development. J. Res. Personal. 39 , 166–184 (2005).

Bollich-Ziegler, K. L., Beck, E. D., Hill, P. L. & Jackson, J. J. Do correctional facilities correct our youth?: effects of incarceration and court-ordered community service on personality development. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 121 , 894–913 (2021).

Lücke, A. J., Quintus, M., Egloff, B. & Wrzus, C. You can’t always get what you want: the role of change goal importance, goal feasibility and momentary experiences for volitional personality development. Eur. J. Personal. 35 , 690–709 (2021).

Gallagher, P., Fleeson, W. & Hoyle, R. A self-regulatory mechanism for personality trait stability: contra-trait effort. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2 , 333–342 (2011).

Verplanken, B. & Orbell, S. Attitudes, habits, and behavior change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 73 , 327–352 (2022).

Hudson, N. W., Fraley, R. C., Briley, D. A. & Chopik, W. J. Your personality does not care whether you believe it can change: beliefs about whether personality can change do not predict trait change among emerging adults. Eur. J. Personal. 35 , 340–357 (2021).

Macnamara, B. N. & Burgoyne, A. P. Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychol. Bull. 149 , 133–173 (2023).

Quoidbach, J., Gilbert, D. T. & Wilson, T. D. The end of history illusion. Science 339 , 96–98 (2013).

Williams, P. G., Smith, T. W., Gunn, H. E. & Uchino, B. N. in The Handbook of Stress Science: Biology, Psychology, and Health 231–245 (Springer, 2011).

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C. & Schilling, E. A. Effects of daily stress on negative mood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57 , 808–818 (1989).

Mroczek, D. K. & Almeida, D. M. The effect of daily stress, personality, and age on daily negative affect. J. Pers. 72 , 355–378 (2004).

Cattran, C. J., Oddy, M., Wood, R. L. & Moir, J. F. Post-injury personality in the prediction of outcome following severe acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 25 , 1035–1046 (2011).

James, B. D. & Bennett, D. A. Causes and patterns of dementia: an update in the era of redefining Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Public. Health 40 , 65–84 (2019).

Denissen, J. J. A., Luhmann, M., Chung, J. M. & Bleidorn, W. Transactions between life events and personality traits across the adult lifespan. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 116 , 612–633 (2019).

Specht, J., Egloff, B. & Schmukle, S. C. Stability and change of personality across the life course: the impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101 , 862–882 (2011).

Hudson, N. W. & Roberts, B. W. Social investment in work reliably predicts change in conscientiousness and agreeableness: a direct replication and extension of Hudson, Roberts, and Lodi-Smith (2012). J. Res. Personal. 60 , 12–23 (2016).

Hutteman, R., Hennecke, M., Orth, U., Reitz, A. K. & Specht, J. Developmental tasks as a framework to study personality development in adulthood and old age. Eur. J. Personal. 28 , 267–278 (2014).

Roberts, B. W. et al. A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention. Psychol. Bull. 143 , 117–141 (2017).

West, P. & Sweeting, H. Fifteen, female and stressed: changing patterns of psychological distress over time. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat. 44 , 399–411 (2003).

Koval, P. et al. Emotion regulation in everyday life: mapping global self-reports to daily processes. Emotion 23 , 357–374 (2023).

Brockman, R., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. & Kashdan, T. Emotion regulation strategies in daily life: mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 46 , 91–113 (2017).

Rauthmann, J. F., Sherman, R. A. & Funder, D. C. Principles of situation research: towards a better understanding of psychological situations. Eur. J. Personal. 29 , 363–381 (2015).

Kuper, N. et al. Individual differences in contingencies between situation characteristics and personality states. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 123 , 1166–1198 (2022).

Mischel, W. Toward an integrative science of the person. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55 , 1–22 (2004).

Beck, E. D. & Jackson, J. J. Personalized prediction of behaviors and experiences: an idiographic person–situation test. Psychol. Sci. 33 , 1767–1782 (2022).

Barlow, D. H. et al. The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis-specific protocols for anxiety disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. 74 , 875–884 (2017).

Sauer-Zavala, S. et al. Countering emotional behaviors in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 11 , 328–338 (2020).

Aarts, H. & Dijksterhuis, A. Habits as knowledge structures: automaticity in goal-directed behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78 , 53–63 (2000).

Neal, D. T., Wood, W., Labrecque, J. S. & Lally, P. How do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual triggers of habits in daily life. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48 , 492–498 (2012).

Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. Social norms and human cooperation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8 , 185–190 (2004).

Bicchieri, C. The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms xvi, 260 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006).

Fehr, E. & Schurtenberger, I. Normative foundations of human cooperation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2 , 458–468 (2018).

Morris, M. W., Hong, Y., Chiu, C. & Liu, Z. Normology: integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 129 , 1–13 (2015).

Cialdini, R. B. & Trost, M. R. Social influence: social norms, conformity and compliance. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55 , 591–621 (1998).

Dempsey, R. C., McAlaney, J. & Bewick, B. M. A critical appraisal of the social norms approach as an interventional strategy for health-related behavior and attitude change. Front. Psychol. 9 , 2180 (2018).

Hoff, K. A., Einarsdóttir, S., Chu, C., Briley, D. A. & Rounds, J. Personality changes predict early career outcomes: discovery and replication in 12-year longitudinal studies. Psychol. Sci. 32 , 64–79 (2021).

Sutin, A. R., Costa, P. T., Miech, R. & Eaton, W. W. Personality and career success: concurrent and longitudinal relations. Eur. J. Personal. 23 , 71–84 (2009).

Bleidorn, W. & Hopwood, C. J. A motivational framework of personality development in late adulthood. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 55 , 101731 (2024). This theoretical account of personality development focuses on motivational aspects to explain normative ageing.

Raison, C. L., Capuron, L. & Miller, A. H. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 27 , 24–31 (2006).

Miller, G. E., Rohleder, N. & Cole, S. W. Chronic interpersonal stress predicts activation of pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways 6 months later. Psychosom. Med. 71 , 57–62 (2009).

McEvoy, J. W. et al. Relationship of cigarette smoking with inflammation and subclinical vascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35 , 1002–1010 (2015).

Deary, I. J. et al. Age-associated cognitive decline. Br. Med. Bull. 92 , 135–152 (2009).

Salthouse, T. A. When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiol. Aging 30 , 507–514 (2009).

Boyle, P. A. et al. Much of late life cognitive decline is not due to common neurodegenerative pathologies. Ann. Neurol. 74 , 478–489 (2013).

Balsis, S., Carpenter, B. D. & Storandt, M. Personality change precedes clinical diagnosis of dementia of the Alzheimer type. J. Gerontol. B 60 , P98–P101 (2005).

Terracciano, A., Stephan, Y., Luchetti, M., Albanese, E. & Sutin, A. R. Personality traits and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. J. Psychiat. Res. 89 , 22–27 (2017).

Sala, G. et al. Near and far transfer in cognitive training: a second-order meta-analysis. Collabra Psychol . 5 , https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/9efqd (2019).

Olaru, G. et al. Personality change through a digital-coaching intervention: using measurement invariance testing to distinguish between trait domain, facet, and nuance change. Eur. J. Personal. 38 , https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070221145088 (2022).

Moreau, D. How malleable are cognitive abilities? A critical perspective on popular brief interventions. Am. Psychol. 77 , 409–423 (2022).

Boyd, E. M. & Fales, A. W. Reflective learning: key to learning from experience. J. Humanist. Psychol. 23 , 99–117 (1983).

Stedmon, J. & Dallos, R. Reflective Practice in Psychotherapy and Counselling (McGraw-Hill Education, 2009).

Keefe, J. R. et al. Reflective functioning and its potential to moderate the efficacy of manualized psychodynamic therapies versus other treatments for borderline personality disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 91 , 50–56 (2023).

Lenhausen, M. R., Bleidorn, W. & Hopwood, C. J. Effects of reference group instructions on big five trait scores. Assessment 31 , https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911231175850 (2023).

Oltmanns, J. R., Jackson, J. J. & Oltmanns, T. F. Personality change: longitudinal self–other agreement and convergence with retrospective reports. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 118 , 1065–1079 (2020).

Credé, M., Bashshur, M. & Niehorster, S. Reference group effects in the measurement of personality and attitudes. J. Pers. Assess. 92 , 390–399 (2010).

Wrzus, C., Quintus, M. & Egloff, B. Age and context effects in personality development: a multimethod perspective. Psychol. Aging 38 , 1–16 (2023).

Jackson, J. J., Connolly, J. J., Garrison, S. M., Leveille, M. M. & Connolly, S. L. Your friends know how long you will live: a 75-year study of peer-rated personality traits. Psychol. Sci. 26 , 335–340 (2015).

Wright, A. J. et al. Prospective self- and informant-personality associations with inflammation, health behaviors, and health indicators. Health Psychol. 41 , 121–133 (2022).

Smith, T. W. et al. Associations of self-reports versus spouse ratings of negative affectivity, dominance, and affiliation with coronary artery disease: where should we look and who should we ask when studying personality and health? Health Psychol. 27 , 676–684 (2008).

Lenhausen, M., van Scheppingen, M. A. & Bleidorn, W. Self–other agreement in personality development in romantic couples. Eur. J. Personal. 35 , 797–813 (2021).

Rothman, A. J., Sheeran, P. & Wood, W. Reflective and automatic processes in the initiation and maintenance of dietary change. Ann. Behav. Med. 38 , s4–s17 (2009).

Caspi, A. & Roberts, B. W. Personality development across the life course: the argument for change and continuity. Psychol. Inq. 12 , 49–66 (2001).

Seger, C. A. Implicit learning. Psychol. Bull. 115 , 163–196 (1994).

Reber, P. J. The neural basis of implicit learning and memory: a review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging research. Neuropsychologia 51 , 2026–2042 (2013).

Back, M. D. & Nestler, S. in Reflective and Impulsive Determinants of Human Behavior 137–154 (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2017).

Hofmann, W., Friese, M. & Roefs, A. Three ways to resist temptation: the independent contributions of executive attention, inhibitory control, and affect regulation to the impulse control of eating behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45 , 431–435 (2009).

Gassmann, D. & Grawe, K. General change mechanisms: the relation between problem activation and resource activation in successful and unsuccessful therapeutic interactions. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 13 , 1–11 (2006).

Anusic, I. & Schimmack, U. Stability and change of personality traits, self-esteem, and well-being: introducing the meta-analytic stability and change model of retest correlations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110 , 766–781 (2016).

Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Jr Intra-individual change in personality stability and age. J. Res. Personal. 44 , 31–37 (2010).

Jackson, J. J., Beck, E. D. & Mike, A. in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research 4th edn, 793–805 (The Guilford Press, 2021). This article provides an overview of interventions that attempt to change constructs related to personality.

Headey, B. Life goals matter to happiness: a revision of set-point theory. Soc. Indic. Res. 86 , 213–231 (2007).

Clark, A. E., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y. & Lucas, R. E. Lags and leads in life satisfaction: a test of the baseline hypothesis. Econ. J. 118 , F222–F243 (2008).

Schwaba, T. & Bleidorn, W. Personality trait development across the transition to retirement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 116 , 651–665 (2019).

Wright, A. J. & Jackson, J. J. The associations between life events and person-centered personality consistency. J. Pers. 92 , 162–179 (2024).

Asselmann, E. & Specht, J. Testing the social investment principle around childbirth: little evidence for personality maturation before and after becoming a parent. Eur. J. Personal. 35 , 85–102 (2020).

Denissen, J. J. A., Ulferts, H., Lüdtke, O., Muck, P. M. & Gerstorf, D. Longitudinal transactions between personality and occupational roles: a large and heterogeneous study of job beginners, stayers, and changers. Dev. Psychol. 50 , 1931–1942 (2014).

Roberts, B. W., Wood, D. & Caspi, A. in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research 3rd edn, 375–398 (The Guilford Press, 2008).

Roberts, B. W. Personality development and organizational behavior. Res. Organ. Behav. 27 , 1–40 (2006).

Schneider, B., Smith, D. B., Taylor, S. & Fleenor, J. Personality and organizations: a test of the homogeneity of personality hypothesis. J. Appl. Psychol. 83 , 462–470 (1998).

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W. & Shiner, R. L. Personality development: stability and change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56 , 453–484 (2005).

Mühlig-Versen, A., Bowen, C. E. & Staudinger, U. M. Personality plasticity in later adulthood: contextual and personal resources are needed to increase openness to new experiences. Psychol. Aging 27 , 855–866 (2012).

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D. & Tice, D. M. The strength model of self-control. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 16 , 351–355 (2007).

Buyalskaya, A. et al. What can machine learning teach us about habit formation? Evidence from exercise and hygiene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120 , e2216115120 (2023).

Jackson, J. J., Hill, P. L., Payne, B. R., Roberts, B. W. & Stine-Morrow, E. A. Can an old dog learn (and want to experience) new tricks? Cognitive training increases openness to experience in older adults. Psychol. Aging 27 , 286–292 (2012).

Beck, E. D. & Jackson, J. J. Idiographic personality coherence: a quasi experimental longitudinal ESM study. Eur. J. Personal. 36 , 391–412 (2022).

Caspi, A. & Moffitt, T. E. When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence. Psychol. Inq. 4 , 247–271 (1993).

Vygotsky, L. S. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Harvard Univ. Press, 1978).

Foa, E. B. & McLean, C. P. The efficacy of exposure therapy for anxiety-related disorders and its underlying mechanisms: the case of OCD and PTSD. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 12 , 1–28 (2016).

Swann Jr, W. B., Rentfrow, P. J. & Guinn, J. S. in Handbook of Self and Identity, 367–383 (The Guilford Press, 2003).

Headey, B. & Wearing, A. Personality, life events, and subjective well-being: toward a dynamic equilibrium model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57 , 731–739 (1989).

Roberts, B. W., Caspi, A. & Moffitt, T. E. Work experiences and personality development in young adulthood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84 , 582–593 (2003).

Scollon, C. N. & Diener, E. Love, work, and changes in extraversion and neuroticism over time. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91 , 1152–1165 (2006).

Lüdtke, O., Roberts, B. W., Trautwein, U. & Nagy, G. A random walk down university avenue: life paths, life events, and personality trait change at the transition to university life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101 , 620–637 (2011).

Asselmann, E. & Specht, J. Till death do us part: transactions between losing one’s spouse and the Big Five personality traits. J. Pers. 88 , 659–675 (2020).

Boyce, C. J., Wood, A. M., Daly, M. & Sedikides, C. Personality change following unemployment. J. Appl. Psychol. 100 , 991–1011 (2015).

van Scheppingen, M. A. et al. Personality trait development during the transition to parenthood. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7 , 452–462 (2016).

Gnambs, T. & Stiglbauer, B. No personality change following unemployment: a registered replication of Boyce, Wood, Daly, and Sedikides (2015). J. Res. Personal. 81 , 195–206 (2019).

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Judge, T. A. & Piccolo, R. F. Self-esteem and extrinsic career success: test of a dynamic model. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 57 , 204–224 (2008).

Asselmann, E. & Specht, J. Personality maturation and personality relaxation: differences of the Big Five personality traits in the years around the beginning and ending of working life. J. Pers. 89 , 1126–1142 (2021).

Lenhausen, M. R., Hopwood, C. J. & Bleidorn, W. Nature and impact of reference group effects in personality assessment data. J. Pers. Assess. 105 , 581–589 (2023).

Vaidya, J. G., Gray, E. K., Haig, J. R., Mroczek, D. K. & Watson, D. Differential stability and individual growth trajectories of big five and affective traits during young adulthood. J. Pers. 76 , 267–304 (2008).

Haehner, P. et al. Perception of major life events and personality trait change. Eur. J. Personal. 37 , 524–542 (2022).

Beck, E. D. & Jackson, J. J. Detecting idiographic personality change. J. Pers. Assess. 104 , 467–483 (2022).

Jackson, J. J. & Beck, E. D. Personality development beyond the mean: do life events shape personality variability, structure, and ipsative continuity? J. Gerontol. B 76 , 20–30 (2021).

Haehner, P., Pfeifer, L. S., Fassbender, I. & Luhmann, M. Are changes in the perception of major life events associated with changes in subjective well-being? J. Res. Personal. 102 , 104321 (2023).

Goodwin, R., Polek, E. & Bardi, A. The temporal reciprocity of values and beliefs: a longitudinal study within a major life transition. Eur. J. Personal. 26 , 360–370 (2012).

Zimmermann, J. & Neyer, F. J. Do we become a different person when hitting the road? Personality development of sojourners. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 105 , 515–530 (2013).

Jackson, J. J., Thoemmes, F., Jonkmann, K., Lüdtke, O. & Trautwein, U. Military training and personality trait development: does the military make the man, or does the man make the military? Psychol. Sci. 23 , 270–277 (2012).

Nissen, A. T., Bleidorn, W., Ericson, S. & Hopwood, C. J. Selection and socialization effects of studying abroad. J. Pers. 90 , 1021–1038 (2022).

van Agteren, J. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 631–652 (2021).

Weiss, L. A., Westerhof, G. J. & Bohlmeijer, E. T. Can we increase psychological well-being? The effects of interventions on psychological well-being: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 11 , e0158092 (2016).

Jensen, S. E. et al. Cognitive–behavioral stress management and psychological well-being in HIV+ racial/ethnic-minority women with human papillomavirus. Health Psychol. 32 , 227–230 (2013).

Howells, A., Ivtzan, I. & Eiroa-Orosa, F. J. Putting the ‘app’ in happiness: a randomised controlled trial of a smartphone-based mindfulness intervention to enhance wellbeing. J. Happiness Stud. 17 , 163–185 (2016).

Dwyer, R. J. & Dunn, E. W. Wealth redistribution promotes happiness. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119 , 2211123119 (2022).

White, C. A., Uttl, B. & Holder, M. D. Meta-analyses of positive psychology interventions: the effects are much smaller than previously reported. PLoS ONE 14 , 0216588 (2019).

Friese, M., Frankenbach, J., Job, V. & Loschelder, D. D. Does self-control training improve self-control? A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 12 , 1077–1099 (2017).

Sander, J., Schmiedek, F., Brose, A., Wagner, G. G. & Specht, J. Long-term effects of an extensive cognitive training on personality development. J. Pers. 85 , 454–463 (2017).

Hyun, M.-S., Chung, H.-I. C., De Gagne, J. C. & Kang, H. S. The effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on depression, anger, and self-control for Korean soldiers. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 52 , 22–28 (2014).

Stieger, M., Allemand, M. & Lachman, M. E. Effects of a digital self-control intervention to increase physical activity in middle-aged adults. J. Health Psychol. 28 , 984–996 (2023).

Cerino, E. S., Hooker, K., Goodrich, E. & Dodge, H. H. Personality moderates intervention effects on cognitive function: a 6-week conversation-based intervention. Gerontologist 60 , 958–967 (2020).

LeBouthillier, D. M. & Asmundson, G. J. G. The efficacy of aerobic exercise and resistance training as transdiagnostic interventions for anxiety-related disorders and constructs: a randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 52 , 43–52 (2017).

Barrett, E. L., Newton, N. C., Teesson, M., Slade, T. & Conrod, P. J. Adapting the personality‐targeted preventure program to prevent substance use and associated harms among high‐risk Australian adolescents. Early Interv. Psychiat. 9 , 308–315 (2015).

Fishbein, J. N., Haslbeck, J. & Arch, J. J. Network intervention analysis of anxiety-related outcomes and processes of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for anxious cancer survivors. Behav. Res. Ther . 162 , (2023).

Bateman, A. & Fonagy, P. A randomized controlled trial of a mentalization-based intervention (MBT-FACTS) for families of people with borderline personality disorder. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 10 , 70–79 (2019).

Sauer-Zavala, S., Wilner, J. G. & Barlow, D. H. Addressing neuroticism in psychological treatment. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 8 , 191–198 (2017).

McMurran, M., Charlesworth, P., Duggan, C. & McCarthy, L. Controlling angry aggression: a pilot group intervention with personality disordered offenders. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 29 , 473–483 (2001).

Wells-Parker, E., Dill, P., Williams, M. & Stoduto, G. Are depressed drinking/driving offenders more receptive to brief intervention? Addict. Behav. 31 , 339–350 (2006).

Fisher, B. M. The mediating role of self-concept and personality dimensions on factors influencing the rehabilitative treatment of violent male youthful offenders. (ProQuest Information & Learning, 2002).

Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Cunha, F., Foorman, B. R. & Yeager, D. S. Persistence and fade-out of educational-intervention effects: mechanisms and potential solutions. Psychol. Sci. Public. Interest. 21 , 55–97 (2020).

Hudson, N. W. & Fraley, R. C. Volitional personality trait change: can people choose to change their personality traits? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109 , 490–507 (2015).

Allemand, M. & Martin, M. On correlated change in personality. Eur. Psychol. 21 , 237–253 (2016).

Luhmann, M., Fassbender, I., Alcock, M. & Haehner, P. A dimensional taxonomy of perceived characteristics of major life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 121 , 633–668 (2021).

Boyatzis, R. E. & Akrivou, K. The ideal self as the driver of intentional change. J. Manag. Dev. 25 , 624–642 (2006).

Dweck, C. S. Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 17 , 391–394 (2008).

Baumeister, R. F. in Can Personality Change? (eds Heatherton, T. F. & Weinberger, J. L.) 281–297 (American Psychological Association, 1994).

Hudson, N. W. & Fraley, R. C. in Personality Development Across the Lifespan (ed. Specht, J.) 555–571 (Academic Press, 2017).

Roberts, B. W., O’Donnell, M. & Robins, R. W. Goal and personality trait development in emerging adulthood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87 , 541–550 (2004).

Winter, D. G., John, O. P., Stewart, A. J., Klohnen, E. C. & Duncan, L. E. Traits and motives: toward an integration of two traditions in personality research. Psychol. Rev. 105 , 230–250 (1998).

Barrick, M. R. & Mount, M. K. The big five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 44 , 1–26 (1991).

Burke, P. J. Identity change. Soc. Psychol. Q. 69 , 81–96 (2006).

Funder, D. C. in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (eds John, O. P., Robins, R. W. & Pervin, L. A.) 568–580 (The Guilford Press, 2008).

Kandler, C. & Zapko-Willmes, A. in Personality Development Across the Lifespan (ed. Specht, J.) 101–115 (Academic Press, 2017).

Lodi-Smith, J. & Roberts, B. W. Social investment and personality: a meta-analysis of the relationship of personality traits to investment in work, family, religion, and volunteerism. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11 , 68–86 (2007).

McAdams, D. P. & Pals, J. L. A new big five: fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. Am. Psychol. 61 , 204–217 (2006).

Kandler, C. Nature and nurture in personality development: the case of neuroticism and extraversion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 290–296 (2012).

McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (eds John, O. P. et al.) 150–181 (The Guilford Press, 2008).

Bleidorn, W. et al. Personality maturation around the world: a cross-cultural examination of social-investment theory. Psychol. Sci. 24 , 2530–2540 (2013).

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R. & Ray, S. A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. J. Bus. Ventur. 18 , 105–123 (2003).

Kazdin, A. E. Behavior Modification in Applied Settings 7th edn (Waveland Press, 2012).

King, L. A. The hard road to the good life: the happy, mature person. J. Humanist Psychol. 41 , 51–72 (2001).

Ozbay, F. et al. Social support and resilience to stress. Psychiat. Edgmont 4 , 35–40 (2007).

Kandler, C. et al. Sources of cumulative continuity in personality: a longitudinal multiple-rater twin study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 98 , 995–1008 (2010).

Bem, D. J. in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Vol. 6 (ed. Berkowitz, L.) 1–62 (Academic Press, 1972).

Staudinger, U. M. Life reflection: a social–cognitive analysis of life review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 5 , 148–160 (2001).

Appenzeller, Z. Dialectical behavior therapy and schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: mechanisms of change and assimilative integration. PhD thesis (ProQuest Information & Learning, 2022).

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C. & Egloff, B. Predicting actual behavior from the explicit and implicit self-concept of personality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97 , 533–548 (2009).

Brandtstädter, J. Personal self-regulation of development: cross-sequential analyses of development-related control beliefs and emotions. Dev. Psychol. 25 , 96–108 (1989).

Krampen, G. Toward an action‐theoretical model of personality. Eur. J. Personal. 2 , 39–55 (1988).

Hogan, R. & Roberts, B. W. A socioanalytic model of maturity. J. Career Assess. 12 , 207–217 (2004).

Arkowitz, H. Toward an integrative perspective on resistance to change. J. Clin. Psychol. 58 , 219–227 (2002).

Fleeson, W., Malanos, A. B. & Achille, N. M. An intraindividual process approach to the relationship between extraversion and positive affect: is acting extraverted as ‘good’ as being extraverted? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83 , 1409–1422 (2002).

Swann, W. B., Stein-Seroussi, A. & Giesler, R. B. Why people self-verify. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 62 , 392–401 (1992).

Wood, D. & Wortman, J. Trait means and desirabilities as artifactual and real sources of differential stability of personality traits. J. Personality 80 , 665–701 (2012).

Zelenski, J. M. et al. Personality and affective forecasting: trait introverts underpredict the hedonic benefits of acting extraverted. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104 , 1092–1108 (2013).

Bradley, G. W. Self-serving biases in the attribution process: a reexamination of the fact or fiction question. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 36 , 56–71 (1978).

Levenson, H. Differentiating among internality, powerful others, and chance. In Research with the Locus of Control Construct (ed. Lefcourt, H. M.) (Academic Press, 1981).

Miller, D. T. Ego involvement and attributions for success and failure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 34 , 901–906 (1976).

Gunty, A. L. et al. Moderators of the relation between perceived and actual posttraumatic growth. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 3 , 61–66 (2011).

Robins, R. W., Noftle, E. E., Trzesniewski, K. H. & Roberts, B. W. Do people know how their personality has changed? Correlates of perceived and actual personality change in young adulthood. J. Pers. 73 , 489–522 (2005).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

Joshua J. Jackson

Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Amanda J. Wright

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joshua J. Jackson .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Jaap Denissen, Ted Schwaba and Cornelia Wrzus for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Jackson, J.J., Wright, A.J. The process and mechanisms of personality change. Nat Rev Psychol 3 , 305–318 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00295-z

Download citation

Accepted : 20 February 2024

Published : 15 March 2024

Issue Date : May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00295-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The dynamic nature of emotions in language learning context: theory, method, and analysis.

- Lesya Ganushchak

- Roel van Steensel

Educational Psychology Review (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Can you change your personality? Psychology research says yes, by tweaking what you think and do

Associate Professor of Psychology & Licensed Clinical Psychologist, University of Kentucky

Disclosure statement

Shannon Sauer-Zavala receives funding from that National Institute of Mental Health to support her research.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Have you ever taken a personality test? If you’re like me, you’ve consulted BuzzFeed and you know exactly which Taylor Swift song “ perfectly matches your vibe .”

It might be obvious that internet quizzes are not scientific, but many of the seemingly serious personality tests used to guide educational and career choices are also not supported by research. Despite being a billion-dollar industry , commercial personality testing used by schools and corporations to funnel people into their ideal roles do not predict career success .

Beyond their lack of scientific support, the most popular approaches to understanding personality are problematic because they assume your traits are static – that is, you’re stuck with the personality you’re born with. But modern personality science studies find that traits can and do change over time .

In addition to watching my own personality change over time from messy and lazy to off the charts in conscientiousness, I’m also a personality change researcher and clinical psychologist . My research confirms what I saw in my own development and in my patients: People can intentionally shape the traits they need to be successful in the lives they want. That’s contrary to the popular belief that your personality type places you in a box, dictating that you choose partners, activities and careers according to your traits.

What personality is and isn’t

According to psychologists, personality is your characteristic way of thinking, feeling and behaving .

Are you a person who tends to think about situations in your life more pessimistically, or are you a glass-half-full kind of person?

Do you tend to get angry when someone cuts you off in traffic, or are you more likely to give them the benefit of the doubt – maybe they’re rushing to the hospital?

Do you wait until the last minute to complete tasks, or do you plan ahead?

You can think of personality as a collection of labels that summarize your responses to questions like these. Depending on your answers, you might be labeled as optimistic, empathetic or dependable.

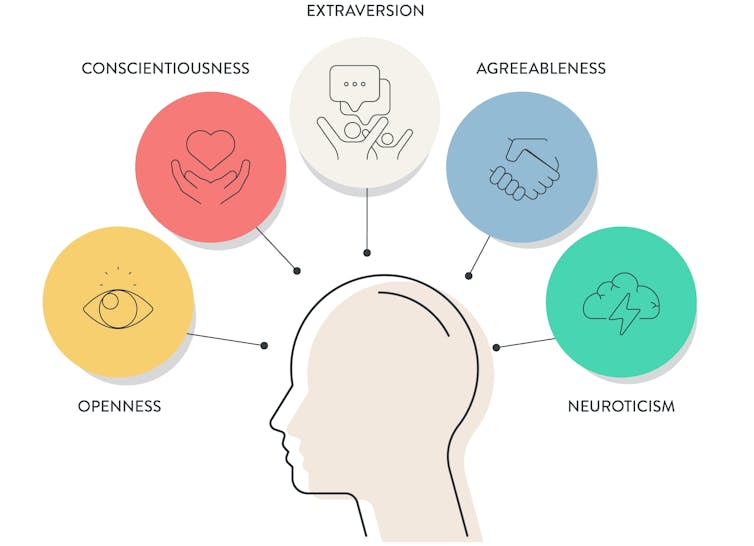

Research suggests that all these descriptive labels can be summarized into five overarching traits – what psychologists creatively refer to as the “Big Five.”

As early as the 1930s, psychologists literally combed through a dictionary to pull out all the words that describe human nature and sorted them in categories with similar themes. For example, they grouped words like “kind,” “thoughtful” and “friendly” together. They found that thousands of words could be accounted for by sorting them between five traits: neuroticism, extroversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness and openness.

What personality is not: People often feel protective about their personality – you may view it as the core of who you are. According to scientific definitions, however, personality is not your likes, dislikes or preferences. It’s not your sense of humor. It’s not your values or what you think is important in life.

In other words, shifting your Big Five traits does not change the core of who you are. It simply means learning to respond to situations in life with different thoughts, feelings and behaviors.

Can you change your personality?

Can personality change? Remember, personality is a person’s characteristic way of thinking, feeling and behaving. And while it might sound hard to change personality, people change how they think, feel and behave all the time.

Suppose you’re not super dependable. If you start to think “being on time shows others that I respect them,” begin to feel pride when you arrive to brunch before your friends, and engage in new behaviors that increase your timeliness – such as getting up with an alarm, setting appointment reminders and so on – you are embodying the characteristics of a reliable person. If you maintain these changes to your thinking, emotions and behaviors over time – voila! – you are reliable. Personality: changed.

Data confirms this idea. In general, personality changes across a person’s life span . As people age, they tend to experience fewer negative emotions and more positive ones, are more conscientious, place greater emphasis on positive relationships and are less judgmental of others.

There is variability here, though. Some people change a lot and some people hold pretty steady. Moreover, studies, including my own , that test whether personality interventions change traits over time find that people can speed up the process of personality change by making intentional tweaks to their thinking and behavior . These tweaks can lead to meaningful change in less than 20 weeks, instead of 20 years.

Cultivating personality traits that serve you best

The good news is that these cognitive-behavioral techniques are relatively simple, and you don’t need to visit a therapist if that’s not something you’re into.

The first component involves changing your thinking patterns – this is the cognitive piece. You need to become aware of your thoughts to determine whether they’re keeping you stuck acting in line with a particular trait. For example, if you find yourself thinking “people are only looking out for themselves,” you are likely to act defensively around others.

The behavioral component involves becoming aware of your current action tendencies and testing out new responses. If you are defensive around other people, they will probably respond negatively to you. When they withdraw or snap at you, for example, it then confirms your belief that you can’t trust others. By contrast, if you try behaving more openly – perhaps sharing with a co-worker that you’re struggling with a task – you have the opportunity to see whether that changes the way others act toward you.

These cognitive-behavioral strategies are so effective for nudging personality because personality is simply your characteristic way of thinking and behaving. Consistently making changes to your perspective and actions can lead to lasting habits that ultimately result in crafting the personality you desire.

- Personality testing

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Personality

- Personality traits

- Personality tests

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges

Case Management Lead (Employment Compliance)

Commissioning Editor Nigeria

Professor in Physiotherapy

Postdoctoral Research Associate

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Towards a Developmentally Integrative Model of Personality Change: A Focus on Three Potential Mechanisms

Elizabeth n riley, sarah j peterson, gregory t smith.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

While the overall stability of personality across the lifespan has been well-documented, one does see incremental changes in a number of personality traits, changes that may impact overall life trajectories in both positive and negative ways. In this chapter, we present a new, developmentally-oriented and integrative model of the factors that might lead to personality change, drawing from the theoretical and empirical work of prior models (e.g. Caspi & Roberts, 2001 ; Roberts et al., 2005 ) as well as from our own longitudinal studies of personality change and risky behavior engagement in children, adolescents, and young adults (Boyle et al., 2016; Riley & Smith, 2016; Riley et al., 2016 ). We focus on change in the trait of urgency, which is a high-risk personality trait that represents the tendency to act rashly when highly emotional. We explore processes of both biologically-based personality change in adolescence, integrating neurocognitive and puberty-based models, as well as behavior-based personality change, in which behaviors and the personality traits underlying those behaviors are incrementally reinforced and shaped over time. One implication of our model for clinical psychology is the apparent presence of a positive feedback loop of risk, in which maladaptive behaviors increase high-risk personality traits, which in turn further increase the likelihood of maladaptive behaviors, a process that continues far beyond the initial experiences of maladaptive behavior engagement. Finally, we examine important future directions for continuing work on personality change, including trauma-based personality change and more directive (e.g., therapeutic) approaches aimed at shaping personality.

Personality is understood to operate as a distal and transdiagnostic contributor to psychological and physical health: numerous studies document that personality predicts life trajectories as reflected in outcomes both positive and negative, in many domains of functioning ( Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007 ). Among the many outcomes predicted by personality are physical health, mortality, marital outcomes, interpersonal functioning, educational and occupational attainment, life happiness, engagement in substance abuse, and psychopathology ( Costa & McCrae, 1996 ; Roberts et al., 2007 ). Increasingly, the importance of personality has become apparent for the prediction of both adult ( Caspi, Harrington, Milne, Amell, Theodore, & Moffitt, 2003 ; Shiner & Masten, 2002 ) and adolescent ( Riley & Smith, in press ; Smith, Guller, & Zapolski, 2013 ) adjustment and behaviors.

Over the past several decades, the conceptualization of personality as dynamic and changing rather than immutably fixed has received more attention in the research literature. The impressive stability of personality across the lifespan has certainly been well documented, but within that overall stability there is also evidence of meaningful change. The recent work on personality development emphasizes both change and continuity across the lifespan and underscores the importance of examining factors that promote each of these processes.

Personality Stability

There are two primary ways in which population-level personality stability and dynamism can be measured: rank-order consistency/change and mean-level consistency/change. The majority of the research documenting personality stability has focused on rank-order consistency. Rank order stability in personality traits has been robustly documented in a number of studies and summarized in meta-analytic studies, and this stability appears to be largely invariant to the particular personality trait, assessment method, and gender of participants ( Roberts, Wood, & Caspi, 2008 ). The Big Five personality traits, Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness, show moderate to high test-retest correlations over long periods of time, with correlations uncorrected for measurement error ranging from .40 to .60 over a decade, and .20 to .40 over several decades. This rank order consistency appears to increase as a function of time/age ( Bazana, Stelmack, & Stelmack, 2004 ; Costa, Herbst, McCrae, & Siegler, 2000 ; Feist & Barron, 2003 ; Fraley & Roberts, 2005 ; Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000 ; Terracciano, Costa, and McCrae, 2006 ).

In their chapter, Roberts, Wood, and Caspi (2008) provide an excellent review of the factors that likely promote personality stability. The authors cite several possible mechanisms of personality consistency, which are: genetic, identity structure/social role, and person by environment interactions/transactions. A great deal of the variance in a person’s personality may be due to predominantly genetic effects (e.g., Lykken & Tellegen, 1996 ; Johnson, McGue, & Krueger, 2005 ), and because an individual’s genome remains fixed over time, all of the personality variance explained by purely genetic effects should also remain stable ( Roberts et al., 2008 ). Concerning identity structure and social role, those authors argue that if an individual maintains a stable social role and sense of identity, or a “stable subjective environment…that transcends the physical environment” (pg. 385), then this will promote stability in the personality traits that match the individual’s sense of identity/social role, at least in the sense of rank-order consistency.

Finally, Roberts et al., (2008) describe a number of person-environment transactions that might serve to promote personality stability: attraction to and selection of environments that reinforce pre-existing personality traits, reactive and evocative transactions that lead to differing subjective effects from objective environments, and manipulative and attrition effects in which individuals can actively change or de-select the environments or situations that are ill-fitted to their already established personality structures. The factors laid out by Roberts and colleagues describe a myriad of ways in which personality continuity and consistency might be promoted over time, and there certainly appears to be merit in investigating the mechanisms by which people stay the same, or even become more like themselves.

It is important to highlight, though, that what we and others refer to as strong stability correlations for traits over time also reflect the presence of substantive change in personality that varies from person to person. Thus, ongoing personality development, change, and growth are important objects of study, just as is the overall stability of personality. The theoretical model we present in this chapter is based on early work in this area and may serve as a guide for future research into personality change.

Mean-level Personality Change over Time

There is even more evidence for personality change when reviewing studies that have examined mean-level changes in population-level personality traits over time. Changes in mean levels of personality traits, or the “amount” of a certain personality characteristic in an individual or population, have been demonstrated across a number of traits and through a number of important developmental time points. While few researchers doubt that these changes in personality do occur, much remains to be learned about the mechanisms that promote them. Caspi and Roberts (2001) proposed four processes that promote personality change. The first is behavior-based personality change. As individuals engage in new behaviors, they experience a range of explicit and implicit contingencies from the behaviors, which can include both reinforcement and punishment. The second is personality change resulting from self-insight or change in self-perception. As individuals watch themselves act in and adapt to new situations, they may gain new insight into themselves, which can result in personality change. The third is intentional or accidental change as a result of observational social learning. Observing the behavior of others and its consequences can involve the observation of which behaviors are reinforced and which are punished, which can alter one’s view of the world and one’s typical behavior patterns. The fourth is change that occurs by way of internalization of feedback from others. One way in which individuals may establish meaning and self-understanding is through feedback from others. Changes in self-understanding can lead directly to changes in personality.

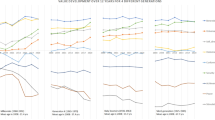

A particularly important factor for personality change seems to be going through a period of transition, such as the transition from adolescence to early adulthood. Early adulthood is thought to be a significant period of mean-level personality change ( Roberts et al., 2006 ). Individuals appear to become less neurotic, more agreeable, more socially dominant, and more conscientious as they go through this transition (e.g., Bleidorn, 2012 ; Roberts, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2003 ; Roberts et al., 2006 ; Roberts et al., 2008 ). This relatively normative process of personality change is sometimes referred to as maturity, and these changes are associated with what are often considered to be “adaptive” life changes such as job attainment and being part of stable and fulfilling relationships or partnerships ( Roberts et al., 2008 ).

One explanatory model for why personality changes occur during times of transition is social investment theory ( Roberts, Wood, & Smith, 2005 ), which posits that periods of transition require individuals to invest in new social roles (such as settling into a relationship, obtaining a job, etc.). New roles come with a specific set of social and personal expectations, as well as contingencies that together create a new environmental reward structure specific to the new social role. Investment in these new social roles prompts necessary changes in personality traits in order to meet the environmental demands of these new social roles. Investment in new social roles requires engagement in new behaviors that are demanded and rewarded by the environmental reward structure specific to the new social role. This process of reward and punishment, in turn, leads to personality change in what is thought of as a bottom-up behavioral fashion. Indeed, Caspi and Roberts (2001) propose that while there are several processes in personality development that promote change, the behavioral models seem to be the most powerful.

There have been several longitudinal studies that demonstrate personality change over long time frames, the results of which seem to be consistent with the social investment theory framework. Roberts, Caspi, and Moffitt (2001) report findings of both continuity and change in a longitudinal study of a young adult cohort followed from the age of 18 to the age of 26. Their results do indicate a degree of personality continuity, but they also found evidence of significant mean-level personality change during this transitional period. Over the 8-year time span, individuals became more mature: they demonstrated more control and social confidence, and less anger and alienation ( Roberts et al., 2001 ). From the ages of 18–26, individuals are taking on new social roles, such as obtaining jobs and investing in relationships, inherent to which are behavioral demands that necessitate a high degree of maturity. Thus, changes in personality that reflect general growth towards maturity fit well with social investment theory.

There is also evidence for personality change over shorter time spans in which significant role change occurs. Bleidorn (2012) followed a sample of German high school students over the course of one year as they were undergoing the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Even during this short observational period, adolescents demonstrated significant personality change that was consistent with maturation, and was most pronounced for the trait of conscientiousness ( Bleidorn, 2012 ). This research is also consistent with the social investment theory observation that when faced with social role transitions, individuals respond by engaging in role-appropriate behaviors, even over short intervals of time.

Mean-level personality change during the transition from adolescence to early adulthood is generally characterized, overall, as maturity: increases in emotional stability, conscientiousness, social dominance, and agreeableness are both normative and adaptive. Notably, however, there has been some research examining processes of personality change that occur in the opposite direction of what is normative and expected. There is some evidence for personality change in the more maladaptive direction across role transitions when individuals respond to those transitions in dysfunctional ways (i.e., social role de-investment). Persons studied from age 18 to 26 who engaged in counterproductive role behaviors, such as stealing from the workplace, fighting with co-workers, and using substances on the job, developed increased levels of negative emotionality and decreased constraint across that transitional period ( Roberts, Walton, Bogg, and Caspi, 2006 ). This finding suggests that, just as engagement in positive, prosocial behaviors can lead to personality change in an adaptive direction, engagement in negative behaviors can lead to personality change in a maladaptive direction.

Jackson, Thoemmes, Jonkmann, Ludtke, and Trautwein (2012) explored changes in personality following military training in a population of German young adults. Individuals who had undergone military training had lower levels of agreeableness following training compared to a control group; strikingly, these personality changes persisted five years after training, even after military-trained participants had gone to college or entered the work force ( Jackson et al., 2012 ). The results of this study indicate that transitional periods marked by highly specific and particular experiences such as military training can produce significant and long-lasting personality change. The Jackson et al., (2012) study documents decreases in agreeableness, a type of personality change that is contrary to the normative and expected processes of personality change in young adults (e.g., increases in agreeableness in line with the maturity principle; Roberts et al., 2008 ) and that many would consider to be possibly maladaptive. It seems likely that decreases in agreeableness may have been reinforced by the environment of military training and may in fact have been beneficial and adaptive for that situation. Thus, as with any discussion of personality traits being adaptive or maladaptive, it is important to consider them in the context of the situation(s) in which the traits are developed or active.

The intent of this chapter is to further develop theory of personality change across the lifespan, with a focus on exploring particular mechanisms of change. We hypothesize and highlight three core potential contributors of personality change, and we will address each in turn: (1) environmental/incidental personality change, whenever new behaviors are reinforced by the environment, the personality dispositions that underlie the behaviors are also reinforced; (2) change predicted by a specific, affect-loaded event(s) such as psychological trauma; and (3) direct and intentional personality change, in which interventions tailored to alter a personality disposition can produce change in the trait.

Environmental/Incidental Personality Change

The incidental/environmental hypothesis of personality change posits that whenever new behaviors are reinforced by the environment, the personality dispositions that underlie the behaviors are also reinforced. In a new context, it is often the case that new behaviors are reinforced. By definition, over time, those reinforced behaviors are exhibited more and more frequently. Slowly and over time, the personality dispositions that underlie the newly reinforced behaviors are themselves reinforced, because they contribute to a reinforced behavior. In this way, engagement in new behaviors that are rewarded by the environment leads to incremental personality change through a bottom-up behavioral process.

This hypothesis is perhaps an extension of social investment theory, which states that whenever a new social role is adopted, a new environmental reward structure specific to that social role is established (e.g., Roberts et al., 2005 ); individuals who invest in their new social role are more likely to engage in behaviors that are consistent with the roles and the environmental reward structure that surrounds the role. Social investment theory is consistent with our claim that personality change is subsequent to behavioral change that results from individuals responding to environmental contingencies.

There has been one set of studies, conducted in our laboratory, documenting the incidental/environmental hypothesis, in which engagement in novel, non-normative behaviors predicts significant, consistent and robust personality change across an important developmental transition. These studies focus on personality change within the high-risk trait of urgency, which reflects the tendency to act rashly when highly emotional, a trait that has two facets: negative urgency and positive urgency ( Cyders & Smith, 2008 ). The traits refer to the tendency to act rashly when distressed or when in an unusually positive mood, respectively. Urgency predicts engagement in, and early onset of, drinking, binge eating, and smoking among early adolescents ( Guller, Zapolski, & Smith, in press ; Pearson, Combs, Zapolski, & Smith, 2012 ; Settles, Fischer, Cyders, Combs, Gunn, & Smith, 2014). Each of these behaviors is thought to provide negative reinforcement in the form of distraction from distress, as well as positive reinforcement in the form of (a) social facilitation from drinking and smoking and (b) pleasurable food consumption from binge eating ( Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991 ; Hersh & Hussong, 2009 ; Small, Jones-Gotman, & Dagher, 2003 ). These forms of reinforcement are thought to occur promptly during and immediately after engagement in the behaviors.

Engagement in these maladaptive behaviors when emotional appears to be both negatively and positively reinforced, and elevations in the personality trait of urgency predict engaging in these behaviors. To study the incidental/environmental, behavior-based, bottom-up hypothesis of personality change, we conducted a set of investigations into the possibility that engaging in those behaviors, which are understood to provide reinforcement, predicted subsequent increases in the trait of urgency. Specifically, we tested whether, just as urgency leads to engagement in the behaviors, perhaps engagement in the behaviors, in turn, leads to subsequent increases in urgency. That is, we hypothesized a reciprocal relationship between the maladaptive behaviors and urgency.

To engage in alcohol consumption, binge eating, and smoking behavior during early adolescence is both rare ( Chung et al., 2012 ; Combs, Pearson, Zapolski, & Smith, 2012 ) and a departure from adaptive, prosocial behavior. In a set of recent longitudinal studies ( Burris, Riley, Puelo, & Smith, 2017 ; Riley, Davis, & Smith, 2016; Riley, Rukavina, & Smith, 2016 ), we followed a sample of 1,906 youth across 8 waves from the spring of 5th grade (the last year of elementary school) through the spring of 9th grade (the first year of high school). Participants completed surveys assessing both urgency and engagement in risky, maladaptive behaviors such as drinking, smoking and binge eating.

Using 8 longitudinal data points, we tested time-lagged predictions. For example, we tested whether Wave 1 urgency predicted Wave 2 drinking, above and beyond prediction from Wave 1 drinking. We also tested whether Wave 1 drinking predicted Wave 2 urgency, above and beyond prediction from Wave 1 urgency. For each of the behaviors studied (drinking, binge eating, and smoking), urgency predicted increases in the behavior beyond prediction from behavior at the prior wave. The key finding with respect to personality change was that it was also true that for each of the three behaviors, engagement in the behavior predicted increases in urgency above and beyond prior levels of the trait ( Burris et al., 2017 ; Riley, Davis, & Smith, 2016; Riley, Rukavina, & Smith, 2016 ). These findings constitute the first documentation that engagement in risky, maladaptive, non-normative behaviors predict subsequent maladaptive changes in personality during the early adolescent years. It appears that youth who enter into the adolescent years either (a) engaging in risky behaviors or (b) with unusually high levels of urgency are at risk to experience a process of progressively increasing personality risk and progressively greater engagement in maladaptive behaviors.

Although we see the results of these three studies as compelling evidence for environmentally- and behaviorally-promoted personality change, it may not be the case that personality change was caused simply by engaging in drinking, smoking, or binge eating. Rather, these behaviors may be best understood as important markers of a set of changes, involving behavior, peer affiliation, self-perception, and the like that, together, result in personality change. Thus, we do not consider the findings of these studies to indicate that behavior-based change operates independently of other factors to produce personality change. Following classic models of developmental psychopathology ( Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002 ), we believe that a complex, interacting process of engagement in new behaviors, new self-perceptions, new peer affiliations, new observational learning, and internalization of new feedback from others combine to facilitate real, meaningful personality change. Certainly, more direct tests of the incidental/environmental behavioral hypothesis of personality change are needed, but the research support for this theory appears promising: when new behaviors are reinforced, the personality dispositions that underlie the behaviors are also reinforced, a process that leads to incremental personality change over time.

Personality Change as a Result of an Affect-Laden Event

Another mechanism by which personality change might occur is through (or subsequent to) the experience of a highly emotional event, such as a trauma. The idea of personality change following trauma is not new: indeed, the possibility that a traumatic event alters personality was described in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) as Enduring Personality Change after a Catastrophic Experience (EPCACE; World Health Organization, 1992 ). Other authors have proposed an actual post-traumatic personality disorder, stating that “severe, unresolved chronic traumatization in childhood leads to more than a collection of symptoms - it actually shapes the personality, meeting the definition of a personality disorder according to the DSM-IV” (p. 88, Classen, Pain, Field & Woods, 2006 ). Research in the field of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex-PTSD (CPSD) often highlights the possibility of personality change post-trauma ( Beltran & Silove, 1999 ). While several authors have proposed the inclusion of personality change as a function of trauma as an actual criterion for CPSD, this process has not yet received much attention in the research literature ( Resnick et al., 2012 ).

There has been some research documenting that the existence of certain pre-trauma personality traits/profiles may predispose some individuals to being vulnerable to develop PTSD following trauma exposure (e.g., higher levels of neuroticism; Fauerbach, Lawrence, Schmidt, Minster, & Costa, 2000 ; Holeva & Tarrier, 2001 ), and some research showing that individuals who have developed PTSD often demonstrate higher levels of neuroticism, lower levels of extraversion, and lower levels of agreeableness ( Breslau, Davis, Andreski, & Peterson, 1991 ; Chung, Berger, & Rudd, 2007 ; Chung, Dennis, Easthope, Werrett, & Farmer, 2005 ). Rigorous, prospective research on personality change following distinct, adverse life events is limited but growing.

Löckenhoff, Terracciano, Patriciu, Eaton, and Costa (2009) examined longitudinal personality change following adverse life events in a large, East Baltimore sample. These authors assessed the five-factor model personality traits (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness) twice over an average interval of 8 years; 25% of the sample reported experiencing a traumatic event within 2 years before the second personality assessment. The participants who reported having experienced a traumatic life event showed increases in neuroticism, decreases in the compliance facet of agreeableness, and decreases in openness to values following the trauma ( Löckenhoff et al., 2009 ). While the effect sizes of personality change found in this study are small, the observed changes in personality following the adverse event were, on average, 3 or more t -score points; the authors note that this change is 3 times larger than the expected amount of age-related change that would be expected in a comparable sample over a similar, 8-year interval, about one t -score point per decade ( Löckenhoff et al., 2009 ; Terracciano, McCrae, Brant, & Costa, 2005 ).