Academic Resources

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Catalog

- Academic Success

- BlueM@il (Email)

- Campus Connect

- Desire2Learn (D2L)

Campus Resources

- Campus Security

- Campus Maps

University Resources

- Technology Help Desk

Information For

- Alumni & Friends

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Teaching Guides

- How Students Learn

- Course Design

- Instructional Methods

- Assignment Design

- Exit Tickets and Midterm Surveys

- Direct vs. Indirect Assessment

Assessment and Bias

- Low-Stakes Assignments

- High-Stakes Assignments

- Responding to Plagiarism

- Assessing Reflection

- Submitting Grades

- Learning Activities

- Flex Teaching

- Online Teaching

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Reflective Practice

- Inclusive Teaching

- Teaching at DePaul

- Support Services

- Technology Tools

Teaching Commons > Teaching Guides > Feedback & Grading > Assessment and Bias

Bias in assessment can affect both students and instructors. As instructors, it's important to reduce unintentional bias in our assessments and to understand how a perceived threat of bias can affect student performance.

Confirmation Bias

One of the most common types of bias that may affect our assessments is confirmation bias. Confirmation bias occurs because people tend to focus on evidence that “confirms” their existing beliefs or theories and dismiss evidence that does not support these beliefs or theories. The problem with this type of bias is that it often occurs outside of our conscious grading process. For example, you may have two students: student A and student B. Student A works very hard, participates in class, and turns in all work on time. Student B, on the other hand, is frequently on her phone during class and submits work late. If these two students submitted the same work, confirmation bias might mean you grade student A's work higher than student B's because you unconsciously look for evidence to support your belief that student A is a harder worker (and deserves a better grade) than student B. While this is the most common sort of confirmation bias we try to guard against, there is a more sinister type that can creep in if an instructor believes that certain groups of students are smarter, harder working, etc. than other students based on group membership alone.

Strategies to Minimize Confirmation Bias

Because we're not fully aware of all of our potential biases, it's important to understand the mechanisms behind these judgment processes, which can have a considerable influence on students’ grades and class experiences.

- One of the best ways to guard against confirmation bias is to grade “blind,” or to block the names of the students you are grading until after you’ve assessed their work. Knowing how to identify biases helps ensures that, consciously or unconsciously, confirmation bias does not taint faculty’s evaluations of students’ work.

- Creating clear and well-defined rubrics is another way to ensure that your grading is more 'objective' and less likely to be affected by confirmation bias.

- While not typically feasible, asking multiple people to assess students' work can also help to reduce the effects of confirmation bias in grading (Steinke & Fitch, 2017).

By knowing how we internalize and process information, we can take the needed steps to be proactive in preventing unintentional bias.

Teaching Confirmation Bias: Examining Urban Legends

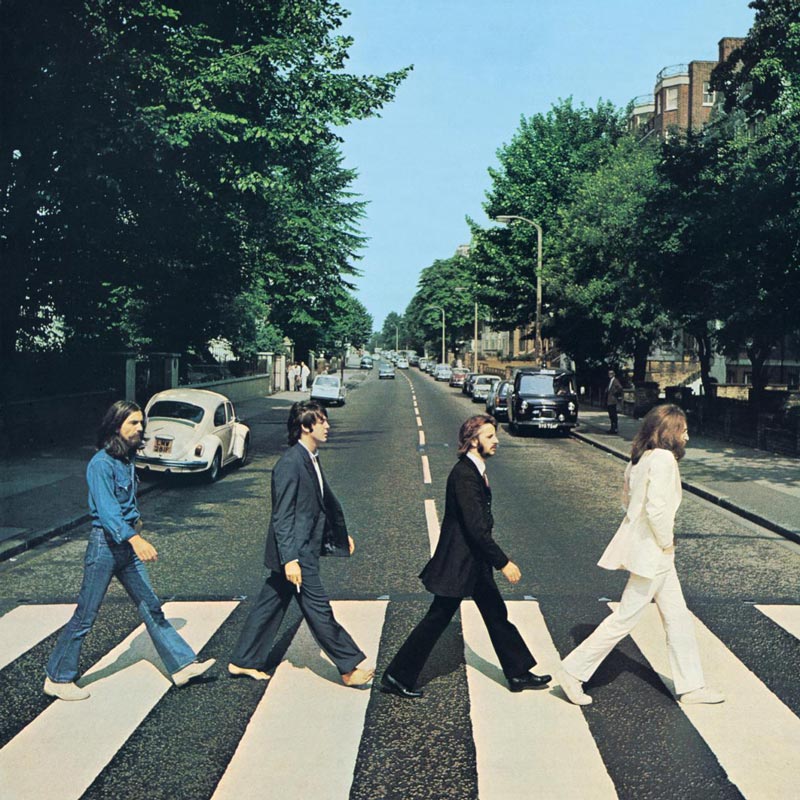

A fun and interesting example that can be used as a class activity is to have students quickly research and discuss an urban legend or celebrity rumor of the day that is accepted as factual. Afterward, you can describe the story of the Beatles and the rumored car crash death of Paul McCartney. What started as prank article in a college newspaper about Paul dying and the Beatles replacing him with a double to hide his death from the public became a phenomenon. The rumor convinced people to infer the distorted and barely audible voice at the very end of “Strawberry Fields Forever” as “I buried Paul.”

They believed the cover of the Abbey Road album, the iconic image of the four band members crossing the road, supported the rumor. In the front is John, whose white suit represented God. Ringo follows, wearing a preacher’s old-fashioned frock coat. After him comes Paul or the look-alike, wearing the conservative suit, which many viewed as corpse dressed for burial. The fact that he was out of step with the others, shoeless and holding a cigarette often called a “coffin nail” was viewed as supporting evidence. George is last, appropriately, because his work shirt and jeans indicate he’s the gravedigger. Nearby, a Volkswagen has a license plate that reads LMW 28IF, which means “Linda McCartney Weeps” (Linda was Paul’s wife) and that Paul would be 28 if he were still alive."

For more information on how this story can be a useful teaching tool, view, " Teaching Confirmation Bias Using the Beatles " by John A. Minahan, PhD.

Stereotype Threat

Stereotype threat is a psychological threat in which members of a particular group are (or believe they are) at risk of conforming to or validating stereotypes about their group. Stereotype threat can create create doubt and anxiety for students if they fear negative stereotypes about one or more of their group memberships will be reinforced by their performance (APA, 2006). Reminders of negative stereotypes can negatively affect a student’s performance on assessment measures. For example, several studies have confirmed that merely mentioning that a stereotype exists lowers students’ grades compared to a control group who did not have the stereotype brought up prior to a test (eg., Steele & Aronson, 1995; Spencer, Steele & Quinn, 1999).

To address the effects of the stereotype, it's essential to have inclusive classrooms. By creating an "identity-safe" classroom faculty can intentionally acknowledge and value students' identities (Steele & Cohn-Vargas, 2014). For example, international students may not be aware of or comfortable with American idioms. However, when faculty acknowledge the sensitivity of the topic, students at risk of stereotype threats can dissociate themselves from the negative stereotypes and better realize their academic potential (McGlone, 2007). Two example strategies for mitigating stereotype threat include using positive imagery (asking students to think of a time that they've done well in the topic being tested, for example) and addressing stereotype threats directly (warning students the stereotypes exist, dispelling myths, and discussing these myths directly with students).

For more information on how stereotype threat impacts academic performance, view the American Psychological Association article, " Stereotype Threat Widens Achievement Gap ."

Further Reading

Aronson, J., & Williams, J. (2004). Stereotype threat: Forewarned is forearmed. Unpublished manuscript, New York University, New York.

Bowen, Natasha K. Wegmann, Kate M. Webber, Kristina C. (2013). Enhancing a brief writing intervention to combat stereotype threat among middle-school students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 427-435.

Nickerson, R.S. (1998). Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises . Review of General Psychology 2(2), 175-220.

American Psychological Association (2006). Stereotype threat widens achievement gap. https://www.apa.org/research/action/stereotype . Retrieved January 2019.

McGlone, Matthew. (2007). Communicative Strategies for Mitigating Stereotype Threat Among Female Students in Mathematics Testing. Conference Papers -- International Communication Association . Annual Meeting, 1-27.

Spencer, S.J., Steele, C.M. & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s m ath performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 35 (1), 4-28.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69 (5), 797-811.

Steele, D., and B. Cohn-Vargas. " Cre ating an Identity-Safe Classroom." Edu topia . 21 October 2015

Steinke, P. & Fitch, P. Minimizing Bias When Assessing Student Work . (2017). Research and Practice in Assessment 12, 87-95.

Identify and Address Bias in Academic Assessment

.jpg)

Professors want a fair and equitable learning experience for their students. However, bias often finds its way into the classroom, particularly through academic assessment.

What is Assessment bias?

Academic assessment bias refers to assessments that unfairly penalize or impact students based on their personal characteristics, such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, religion and place of origin.

Education researchers, Kyung Kim and Darya Zabelina, studied cultural bias in academic assessment and found that in standardized and alternative assessments alike, bias often occurs through the measurement of general knowledge normed based on the knowledge and values of majority groups (Kim & Zabelina, 2015). Minority groups and persons with different language backgrounds, socioeconomic statuses and cultures may not be represented in the work, and assessments may not consider the diversity of values, thoughts, opinions and backgrounds (Kim & Zabelina, 2015). It seems we measure against a single state of what is normal, standard, expected.

If test results are interpreted without consideration for cultural and educational factors of different identity groups, assessment scores will inaccurately reflect a student’s true level of ability and competence (Blankenberger et al., 2017). While removing bias from the academic assessment will be an ongoing pursuit for professors, there are specific ways to counter bias and ensure the most equitable learning environment possible where students’ unique abilities and backgrounds are valued in all aspects of a course.

Types of Assessment Bias

To examine for bias, it is important to understand the different ways bias can emerge. There are three main types of bias that arise in academic assessments;

- Construct Bias

Construct bias occurs when the concepts measured are not universal (Van de Vijver & Tanzer, 2004). When itemized objectives are created based on Western concepts, it often does not cover all relevant considerations from a non-Western perspective. The bias, in this scenario, occurs when the indicators of a particular construct do not correspond to a sufficiency or insufficiency ruling of some underlying trait or ability. For example, a student new to the U.S may not know the capital of all 50 states, but this does not mean that they have an inadequate level of geographical knowledge.

- Method Bias

Method bias refers to how the assessment is administered or acquired (Van de Vijver & Tanzer, 2004). Method bias can present in different ways. Students learn differently, and method bias may appear through formal testing where knowledge and understanding are assessed repeatedly in the same way. For example, knowledge and understanding that is always tested through final exams while favour individuals who have experience and a strong foundation in test taking skills.

Item bias refers to the content of an assessment (Van de Vijver & Tanzer, 2004). Instructors must evaluate from an objective perspective and actively work to remove bias from the phrasing and language patterns of assessment questions or activity outlines (Blankenberger et al., 2017). For example, a particular phrasing of a question using western names and language will favour those Western students who grew up with this understanding.

One of the most challenging aspects of assessment bias is that it can occur without professors or students noticing. Professors, or people in general, may hold subconscious biases. Traditional assessment methods that have long been accepted often hold inherent bias. And students may accept biased assessment as an accurate reflection of their learning, which can have detrimental impacts on their academic success and career choices.

Ways to reduce assessment bias .

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

Instructors can remedy assessment bias through instructional design aligned with culturally responsive pedagogy (Kim & Zabelina, 2015). Culturally responsive pedagogy , or culturally relevant teaching, refers to a teaching approach that emphasizes connecting students’ culture and social situations with the school’s curriculum. To achieve this, instructors must include cultural references of students in all aspects of their course. Not only will culturally responsive pedagogy bring instructors closer to achieving bias-free assessment, but it will also create an inclusive class environment where students feel safe and open to contribute their learning, perspectives and experiences in class.

Kritik’s discussion feature allows students to welcome new perspectives, opinions and approaches to learning through interaction with course material in open and organic ways beyond textbooks and lectures. These organic conversations, not only promote inclusive and culturally responsive classrooms, they also enable students to develop deeper understandings of course concepts.

- Alternative Assessments

Taking a purposeful approach to alternative assessment that removes bias and engages students can make a positive difference in the classroom with many rewarding learning outcomes. (Van de Vijver & Tanzer, 2004). With alternative assessments, it is critical to think about what type of alternative assessment is being used, how bias may be involved, and how the specific assessment sets out to engage, challenge and involve students in inclusive learning opportunities. Compared to standardized or traditional testing methods, alternative assessments allow students to work at their own pace and allow flexibility while promoting an empathetic and culturally responsive experience. (Kim & Zabelina, 2015).

One example would be staged inquiry-based learning, where students have time to explore a chosen topic, receive ongoing feedback, with the freedom to research and present their findings in unique ways. With Kritik, students can receive bias-free peer assessment throughout the assignment stages, enhance their work, share their perspectives with their peers, and ensure their work follows the set criteria outlined in the instructors’ provided rubric .

- Adapt Classroom Culture

Assessment bias must be considered before an assignment or activity is assigned. When introducing an assessment, clear communication of expectations is critical. Pre-assignment communication provides students with the opportunity to gain an understanding of expectations and clarify misunderstandings (Kim & Zabelina, 2015).

Rubrics play an essential role in outlining expectations clearly and setting students up for success (Blankenberger et al., 2017). Professors should be open-minded during this process to consider the challenges, perspectives and questions of students. It may be possible that an upcoming assignment is altered based on these discussions. When students feel heard and valued, it will make the following assignments more meaningful and build greater accountability.

Kritik has a repository of customizable rubrics to ensure professors accurately and effectively assess students while providing students with a clear understanding of the assignment expectations so they can focus on doing their best work.

- Group Activities

Coupled with the development of positive classroom culture, group activities are an additional space for students to engage with the course material. Group activities help students learn through teamwork and collaboration (Kim & Zabelina, 2015). Additionally, they provide an opportunity for students to share and value each other’s diverse perspectives and positions. This means that the end product will not only be stronger and find deeper meaning in course topics, but students will develop soft skills through the process.

Kritik enables professors to facilitate both individual peer assessment and group-based peer assessment . Team-based learning is one approach supported by Kritik that allows students to form bonds with a particular group of peers and encourages greater autonomy and responsibility.

- Include More Creative Elements

Finally, creating assessments with opportunities for creative skill development can help alleviate bias. Creativity can be defined as the ability to produce something novel and valuable (Kim & Zabelina, 2015). Creativity leverages intelligence and is a better predictor of creative accomplishments than is IQ (Kim, 2008). Creativity assessment may allow students to be evaluated “based on their actual cognitive ability rather than their ability to adapt to the culture of the majority” (Kim & Zabelina, 2015).

With discussions, anonymous feedback, and customizable rubrics, professors can use Kritik to support and encourage student creativity while defining specific learning outcomes that match with the course curriculum.

Conclusion

Bias won’t be eliminated from school environments. However, taking purposeful action to address and overcome bias in teaching and assessment practices will undoubtedly lead to a more equitable and inclusive learning experience for students and also demonstrate empathy and understanding for all involved. Teaching with cultural considerations, empathy, diverse assessment styles and flexibility are key to supporting equitable opportunities for all students.

Blankenberger, B., Young McChesney, K., Schenbley, S. M., Moranski, K. R., & Dell, H. (2017) Measuring racial bias and general education assessment, Journal of General Education, 66 (1-2), 42-59.

Kim, K. H. (2008). Meta-analyses of the relationship of creative achievement to both IQ and divergent thinking test scores. Journal of Creative Behavior, 42, 106-130.

Kim, K. H., & Zabelina, D. (2015). Cultural bias in assessment: Can creativity assessment help? International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 6 (2), 130-148.

Vijver, F.,& Tanzer, N. K. (2004) Bias and equivalence in cross-cultural assessment: An overview, European Review of Applied Psychology, 52 (2), 119-135.

Get Started Today

Related blogposts.

IMAGES